Genesis B

Genesis B, also known as The Later Genesis, is a passage of Old English poetry describing the Fall of Satan and the Fall of Man, translated from an Old Saxon poem known as the Old Saxon Genesis. The passage known as Genesis B survives as an interpolation in a much longer Old English poem, the rest of which is known as Genesis A, which gives an otherwise fairly faithful translation of the biblical Book of Genesis. Genesis B comprises lines 235-851 of the whole poem.

"ac niotað inc þæs oðres ealles, forlætað þone ænne beam,

wariað inc wið þone wæstm. Ne wyrð inc wilna gæd."

Hnigon þa mid heafdum heofoncyninge

georne togenes and sædon ealles þanc,

lista and þara lara. He let heo þæt land buan,

hwærf him þa to heofenum halig drihten,

stiðferhð cyning. Stod his handgeweorc

somod on sande, nyston sorga wiht

to begrornianne, butan heo godes willan

lengest læsten. Heo wæron leof gode

ðenden heo his halige word healdan woldon.

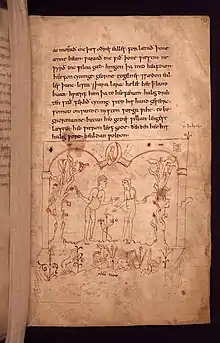

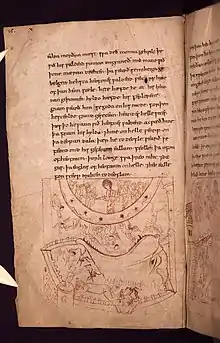

Genesis B and Genesis A survive in the partially illustrated Junius Manuscript. The manuscript is incomplete, having in particular missing pages (conjectured to be two leaves, or four sides) between pages 22 and 23, meaning that the transition point between Genesis A and Genesis B is lost.

Background

Scholars once believed that the legendary first Old English poet Cædmon was responsible for not only the Genesis poems but also the entire Junius Manuscript. This theory has long since been disregarded.[1]

Eduard Sievers realised that Genesis B was originally separate from Genesis A in the 1870s: by philological and stylistic analysis, he showed that these lines must have been translated from an Old Saxon (continental Low German) original. In 1894 his hypothesis was dramatically confirmed by the discovery of parts of the Old Saxon original in a manuscript in the Vatican: about two dozen lines of the Old Saxon text coincide almost word-for-word with part of Genesis B.[2]

Content and controversy surrounding the text

Genesis B is a strikingly original and dramatic retelling of the Fall of the Angels and the Fall of Man.

Genesis B depicts the fall of Lucifer from heaven, at which point he is renamed "Satan" and assumes authority as the ruler of Hell. The text goes on to describe the temptation and subsequent fall of Adam and Eve from God's grace, but the account presented in this manuscript differs largely from any other version. Oldrieve addresses this controversy in terms of the language used to describe Satan's bodily form. According to Genesis B, Satan appears to Adam as an angel, as opposed to the serpent which typically represents Satan.[3] Woolf even goes as far as to compare Satan to Loki of Norse mythology, stating that the similarities between the two are "undoubtedly sufficient".[4] The controversies, however, are not as superficial as the depiction of the devil, which is still crucial to the overall meaning of the poem, but complicate much more significant plot points and characters. One of these major differences that Hill cites is the portrayal of Eve; while Genesis A claims that Eve is motivated by the desire to be more God-like, Genesis B shows that she was tempted by Satan and is instead trying to help save Adam by fulfilling God's wishes.[5] Oldrieve's conclusion that Eve was so deceived by the devil and his words that she believed she saw an angel instead of a serpent blend these two controversies and offer further support of Eve's innocence and lack of manipulation,[6] much like the discrepancy noted by Hill.

The issue of language, the philology, is also a concern of Timmer's, a scholar referenced several times throughout other scholars’ interpretations of Genesis B. He discusses the discrepancies between versions of the fall of Adam and Eve and attributes them to problems with the translation from Old Saxon to Old English, offering reason as to how specific words are construed to have a meaning different than those found in any other Old English manuscript.[7] A different explanation is offered by Doane; he argues that many of the discrepancies are a result of the extended time period between the oral telling of the story and the transcribing of the story by the Old Saxons, causing embellishment to heighten the literary drama of the text.[8]

Translations

Many scholars who translate Genesis B give significant evidence to the reasoning behind their translations, due to the complicated nature of the text. Oldrieve chooses to focus on maintaining the beauty of the text in her translation in order to portray the “vivid and lifelike characterization of Satan, Adam, and Eve”.[9] Similar to Oldrieve, Woolf uses the text to further explore the portrayal of the devil throughout Old English poetry; in Genesis B alone, she compares Satan to Loki, as mentioned before, along with other Norse gods, and Weland of Beowulf, the latter which she cites as Timmer's original idea.[10] Timmer's goal in transcribing the text, since he does not offer a direct translation, was to represent a complete rendering of the text based on manuscripts and several other transcriptions and translations he encountered, similar to Doane. He goes on to acknowledge the discrepancies he still encounters, despite his thorough investigation of the text.[11]

Relationship with Paradise Lost

Genesis B makes Satan a central character, giving him a monologue which provides an extensive opportunity for character development. This literary approach is similar to that of John Milton's seventeenth-century epic Paradise Lost. Since Milton was acquainted with Franciscus Junius (the younger), who owned Julius 11 and made some attempt to read it, it has been speculated that Genesis B was one inspiration for Paradise Lost.[12][13][14]

Editions and translations

- Doane, Alger N. (1991), The Saxon Genesis: an Edition of the West Saxon Genesis B and the Old Saxon Vatican Genesis, Madison: University of Wisconsin, ISBN 978-0299128005.

- Krapp, George Philip, ed. (1931), The Junius Manuscript, The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records: A Collective Edition, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231087650, OCLC 353894.

- Marsden, Richard (2004), "Satan's Challenge (Genesis B, lines 338–441)", The Cambridge Old English Reader, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511817069.022.

- Oldrieve, Susan (13 October 2010), "Genesis B: Introduction and Translation", The Department of English, Baldwin Wallace College.

- Timmer, B. J. (1948), The Later Genesis, Oxford: Scrivener, OCLC 221307034.

References

- Weston Wyly 2007, p. 212.

- Breul 1898, p. 174.

- Oldrieve 2010, para. 3.

- Woolf 1953, p. 2.

- Hill 1975, p. 280.

- Oldrieve 2010, para. 4.

- Timmer 1948, p. 19.

- Doane 1991, p. 48.

- Oldrieve 2010, para. 11.

- Woolf 1953, p. 3.

- Timmer 1948, p. 67.

- Lever 1947.

- Bolton 1974.

- Ramazzina 2016.

Bibliography

- Bolton, W. F. (February 1974), "A Further Echo of the Old English Genesis in Milton's Paradise Lost", Review of English Studies, 25 (97): 58–61, JSTOR 514207

- Breul, Karl (1898), "Eduard Sievers", The Modern Quarterly of Language and Literature, 1 (3): 173–175, JSTOR 41065399

- Doane, Alger N. (1991), The Saxon Genesis: an Edition of the West Saxon Genesis B and the Old Saxon Vatican Genesis, Madison: University of Wisconsin, ISBN 978-0299128005

- Hill, Thomas D. (1975), "The Fall of Angels and Man in the Old English Genesis B", in Lewis E. Nicholson; Dolores Warwick Frese (eds.), Anglo-Saxon Poetry: Essays in Appreciation, For John C. McGalliard, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 279–290, ISBN 9780268005757

- Lever, J. W. (April 1947), "Paradise Lost and the Anglo-Saxon Tradition", The Review of English Studies, 23 (90): 97–106, JSTOR 509621

- Oldrieve, Susan (13 October 2010), Genesis B: Introduction and Translation, The Department of English, Baldwin Wallace College

- Ramazzina, E. (July 2016), "The Old English Genesis and Milton's Paradise Lost: the characterisation of Satan", L'analisi linguistica e letteraria, 24 (1): 89–117

- Timmer, B. J. (1948), The Later Genesis, Oxford: Scrivener, OCLC 221307034

- Weston Wyly, Bryan (2007), "Caedmon the Cowheard and Old English Biblical Verse", in North, Richard; Allard, Joe (eds.), Beowulf and Other Stories: A New Introduction to Old English, Old Icelandic, and Anglo-Norman Literatures, Great Britain: Pearson, pp. 189–218, ISBN 9781408286036

- Woolf, R. E. (1953), "The Devil in Old English Poetry", Review of English Studies, 4 (13): 1–12, JSTOR 510385

Additional reading

- Vickrey, John F. (2015), Genesis B and the Comedic Imperative, Lehigh University Press, ISBN 978-1-61146-167-1