George Escol Sellers

George Escol Sellers (November 26, 1808 – January 1, 1899) was an American businessman, mechanical engineer, and inventor. He owned and managed different businesses and patented many inventions. He established a company with his brother Charles where he patented his early invention of a machinery that produced lead pipe from hot fluid lead continuously. While working for the Panama Railway in 1850s, he received various patents on improvements he made on railroad locomotives, including a railroad engine which could climb steep hills and heavily inclined planes.

George Escol Sellers | |

|---|---|

George Escol Sellers, ca. 1898 | |

| Born | November 26, 1808 |

| Died | January 1, 1899 (aged 90) |

| Nationality | American |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Mechanical engineering |

| Practice name | Nathan & David Sellers, Globe Rolling Mills |

| Employer(s) | Panama Railway |

| Projects | Lead pipes, railroad locomotives |

He was interested in the field of archeology, and wrote many articles, collected artifacts and became a skilled arrowhead maker; some of the latter were on display at the National Museum of the American Indian. He was considered to have an artistic talent and he indulged in arts and the society of artists throughout his life. A character name in the first edition of Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner's The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873) — "Colonel Eschol Sellers" — was similar to Sellers' and had to be changed when he objected to its further use. However, the connection repeated again when the new name — "Colonel Mulberry Sellers" — unintentionally referenced the neighborhood where he was born.

Early life

George Escol Sellers was born on November 26, 1808, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Coleman Sellers and Sophonisba Angusciola Peale.[1][2] His birthplace was near the Philadelphia Mint in the neighborhood of Mulberry Court. He had one elder brother Charles (b. 1806), two younger brothers Harvey (b. 1813) and Coleman Sellers II (b. 1827), and two younger sisters Elizabeth (b. 1810) and Anna (b. 1824).[2]

His father and many ancestors had been engineers. His maternal grandfather was Charles Willson Peale, and his paternal grandfather Nathan Sellers was known for artwork of wire paper molds.[2] While at school, he worked at Peale's Philadelphia Museum — he would later serve as a member of the museum's board of directors.[3] Sellers was educated at public schools and also studied for five years with tutor Anthony Bolmar at the West Chester Academy in West Chester, Pennsylvania.[1][2][4] In 1832, he went to England to study machines used for production of paper.[3]

Career and inventions

Sellers returned to the United States in 1833[3] and started working at his father and grandfather's firm, Nathan & David Sellers; Charles was employed there as well. The company made machinery for producing wire and paper and was the first in the country to use forged frames to build locomotives. They also worked for the United States Mint.[2] When Nathan Sellers died in 1830, the business was reorganized and Coleman Sellers and his two sons then ran the business. As a consequence of the Depression of 1837, the company became insolvent and closed. His work at the firm inspired many of his engineering writings.[1][2]

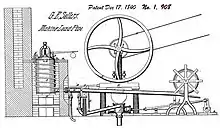

Sellers and Charles moved to Cincinnati, Ohio and established a factory. Sellers invented machinery that utilized hot fluid lead for continuous production of lead pipe — he received a patent for his design, number US1908A on December 17, 1840.[1][2][5] Their business was eventually sold and merged into a company which was a major producer of lead pipe in the country. Sellers then partnered with Josiah Lawrence, a Cincinnati businessman, and organized a wire manufacturing company called Globe Rolling Mills. He incorporated machinery that he designed in their production process and it proved to be more efficient in producing lead pipe and wire.[2][1]

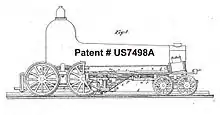

He sold his interest in the company by 1850 and undertook manufacturing of railroad locomotives for the Panama Railway in 1851. Sellers was considered an able engineer and mechanic, and took out many patents on improvements he made on railroad locomotives while working there. He invented a railroad engine capable of climbing steep mountains and heavily inclined planes — it was defined as an engine boiler with gearing for working heavy grades and was patented as US7498A on July 9, 1850.[1][2][6] He was engaged in the manufacturing and sales of railroad equipment for several years in the 1850s.[2][1]

During the American Civil War, Sellers moved to southern Illinois near the Ohio River and became interested in their mining operations.[2][1][3] He invented a process for making paper-stock from vegetable fiber which was patented as US41101A on January 5, 1864.[7] He spent the remainder of his career pursuing mechanical engineering and design.[2][1] In 1888, he took up residence at Chattanooga, Tennessee upon retirement and lived on Mission Ridge.[3] Sellers died at his home in Chattanooga at the age of 90 on January 1, 1899.[8]

Personal life

Sellers married Rachel Brooks Parrish on March 6, 1833. They had five children and adopted an orphaned daughter of his cousin. Parrish died on September 14, 1860 in Illinois and was survived by only one son out of their five children.[3]

He had a deep interest in archaeology. He wrote several articles on the relics of the mound builders of Illinois — one published by Smithsonian Institution was on the aborigines' method of making earthenware salt pans. He also wrote detailed articles on how the local American Indians made arrowheads and stone age tools.[1][2] He personally became so skilled at making arrowheads that some specimens of his craft were on display at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C.[3] He also had a substantial collection of pottery and implements of the prehistoric tribes of the Ohio valley.[1][2]

His grandfather Charles Wilson Peale and his uncles Rembrandt Peale and Raphaelle Peale were notable artists of the time. In Sellers's opinion, Raphaelle was the most talented of Charles's artist children.[9] Sellers also had recognized artistic talent; Thomas Sully had urged him at an early age to become a portraitist and offered to teach him, but he was more interested in pursuing a vocational career.[1][2] Nonetheless, he indulged his taste for arts and the society of artists throughout his life.[1] He patented different art inventions from time to time and coordinated one of the earliest social organizations of artists in Philadelphia.[1][2]

The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today

The first edition of Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner's 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today had a fictional character — a satirical exploitative capitalist without redeeming social values — called "Colonel Eschol Sellers".[10] The name "Eschol Sellers" was suggested by Warner,[3][11] and the use of "Eschol" was a carefully considered decision, with apocryphal descriptions of its antecedents.[3] This is explained further at the beginning of Twain's 1892 novel The American Claimant as being Sellers of Philadelphia, who sued to have his name removed from the novel.[12]

Dr. J. H. Barton — a common friend of Sellers and Warner — discovered the unintentional depiction and urged Warner to not use his friend's name. Warner forwarded a message to Sellers through Barton clarifying that the usage had been unintentional; on January 1, 1874, Sellers replied and asked them to issue a disclaimer stating the same. Warner agreed and also said that the name would be changed in the future copies. While the next editions of the novel removed the name "Eschol", "Colonel Mulberry Sellers" was used instead. "Mulberry" happened to be the name of the neighborhood where Sellers was born and raised, and this unwanted connection continued to be repeated, even unto Sellers's obituaries.[12][3][8][13][14]

Publications

See also

- Alexander Bonner Latta — invented the first practical steam fire engine.

- Anthony Harkness — inventor associated with pioneering the railroad locomotive industry of Cincinnati, Ohio.

References

Citations

- Cope & Ashmead 1904, p. 198.

- McGraw-Hill 1899, p. 256.

- Schmidt, Barbara. "Special Feature: "We will Confiscate His Name": The Unfortunate Case of George Escol Sellers". twainquotes.com. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- "Anthony Bolmar 1797-1861". Emory University. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- "Machinery for making pipes continuously from lead". U.S. Patent Office. December 17, 1840. Retrieved March 25, 2017 – via Google Patents.

- "Boiler and gearing of locomotive-engines for working heavy grades". U.S. Patent Office. July 9, 1850. Retrieved March 25, 2017 – via Google Patents.

- "Improvement in preparing vegetable fiber for paper-stock". U.S. Patent Office. January 5, 1864. Retrieved March 25, 2017 – via Google Patents.

- "Death of George E. Sellers". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. January 2, 1899 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Cikovsky, Nicolai, Jr.; Bantel, Linda; Wilmderding, John. Raphaelle Peale Still Lifes (PDF). New York: National Gallery of Art, Washington; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 115–116. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- "Personal and Political". Humboldt Republican. Humboldt, Iowa. January 12, 1899 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Col. Mulberry Sellers". Independence Daily Reporter. Independence, Kansas. September 3, 1890 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Twain 1898, p. 1.

- "Death of an Old Engineer: George Sellers Dies at His Home on Mission Ridge". The Atlanta Constitution. January 2, 1899. p. 3.

- Wiltse, Henry M. (September 8, 1901). "The Original Col. Mulberry Sellers". The Atlanta Constitution. p. A1.

- Hindle 2012, p. 58.

- Hindle 2012, p. 71.

Sources

- Cope, Gilbert; Ashmead, Henry Graham (1904). Genealogical and Personal Memoirs. 1. Higginson Book Company.

- Hindle, Brooke (2012). Technology in Early America/Needs and Opportunities for Study. Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press.

- McGraw-Hill (1899). George Escol Sellers. American Machinist. McGraw-Hill.

- Twain, Mark (1898). The American Claimant. Harper & Brothers.