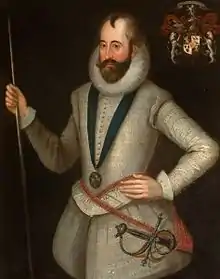

George Home, 1st Earl of Dunbar

George Home, 1st Earl of Dunbar, KG, PC (ca. 1556 – 20 January 1611) was, in the last decade of his life, the most prominent and most influential Scotsman in England. His work lay in the King's Household and in the control of the State Affairs of Scotland and he was the King's chief Scottish advisor. With the full backing and trust of King James he travelled regularly from London to Edinburgh via Berwick-upon-Tweed.

The Earl of Dunbar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 1603–1606 | |

| Preceded by | John Fortescue |

| Succeeded by | Sir Julius Caesar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1556 |

| Died | 20 January 1611 (aged 54-55) |

In Scotland

Home was the third son of Sir Alexander Home of Manderston, Berwickshire, by his spouse Janet, daughter of George Home of Spott. He was introduced, at the age of 26, to the Court of sixteen-year-old James VI by a relative, Alexander Home, 6th Lord Home. Establishing himself as a favourite, he was in the retinue which accompanied King James VI to Norway and Denmark to collect his future Queen. James Melville of Halhill mentions that Home did not sail with the king, but in one of three other ships, along with Lewis Bellenden, John Carmichael, the Provost of Lincluden, William Keith of Delny, James Sandilands, and Peter Young.[1]

During the trip, James VI made him Keeper of the Royal Wardrobe and sacked William Keith of Delny, who had appeared in richer clothing than himself.[2] In 1606, when making him Earl of Dunbar, James VI praised him for his tact and diplomacy in Denmark at this time, his "high prudence and rare discretion."[3]

He was knighted on 4 November 1590, when Alexander Lindsay was made Lord Spynie,[4] and known as "Sir George Home of Primrose Knowe",[5] and after 1593, as "Sir George Home of Spot". Spott is a village in East Lothian. Home had a feud with the previous owner James Douglas. James VI gave Home the rest of the lands of Spott and made them barony for Sir George Hume on 10 June 1592, requesting that Spott castle be the chief residence of the baron, and a feudal duty of a primrose to delivered at Primroseknowe every 25 March.[6]

In the 1590s Home presided over an arrangement where clothes and textiles for the royal households were provided by the goldsmith Thomas Foulis and merchant Robert Jousie, partly financed by money sent as a gift or subsidy to James VI by Queen Elizabeth.[7] Home had a role in financing the household of Anne of Denmark giving her £3833 Scots in 1591, and in 1592 a dividend of £4000 from her dowry which had been invested in various Scottish towns. He was in charge of paying her Danish servants who were owed fees by the Scottish exchequer, totalling £1,200 in 1592.[8]

In November 1592 Home was identified with friends of the Duke of Lennox, Colonel William Stewart, the Laird of Dunipace, Thomas Erskine, and James Sandilands, as a supporter of the king's former favourite James Stewart, Earl of Arran, working for his rehabilitation to the disadvantage of the Chancellor, John Maitland and the Hamilton family. The English diplomat Robert Bowes called this group the "four young and counselling courtiers."[9]

In December 1592 he rode with Sir John Carmichael with news of the crisis caused by the discovery of the Spanish blanks to Alloa Tower, where James VI and Anna of Denmark were celebrating the wedding of the Earl of Mar and Marie Stewart.[10]

In November 1593 Anna of Denmark complained that people around the king were speaking disrespectfully of her. James asked Home to be watchful of the queen's honour. Robert Bowes wrote that Home himself was suspected of speaking against the queen, and Burghley endorsed this, adding "The wolf to be a watchman."[11]

Home was involved in the preparations for the baptism of Prince Henry at Stirling Castle in 1594. He was given £4,000 Scots from the queen's dowry which had been invested with Perth town council. The money was for mending the royal tapestries, making tablecloths for the banquets and the desks in the chapel, and upholstering stools and chairs. The tapestries were repaired by George Stachan or Strathauchin and William Beaton, the court embroiderer, made the other items.[12]

With the king, at Linlithgow Palace, he interviewed a woman from Nokwalter in Perth, Christian Stewart, who was accused of causing the death of Patrick Ruthven by witchcraft. She confessed she had obtained a cloth from Isobel Stewart to bewitch Patrick Ruthven. She was found guilty of witchcraft and burnt on Edinburgh's Castlehill in November 1596.[13] In 1598 he was appointed a Privy Counsellor, and the following year appears as Sheriff of Berwick-upon-Tweed, (by then in England).

In October 1600 James VI visited his house at Spott and was banqueted. The "merry" party included Sir Robert Ker, the Duke of Lennox, Sir Thomas Erskine, and Sir David Murray. The English courtier Roger Aston noted that all the gentlemen of the chamber there were "inward" with one another and with Home, who was the most "inward" with the king. Aston took the opportunity to ride to Berwick-upon-Tweed to see his friends.[14]

In 1601 he was made Master of the King's Wardrobe, and on 31 July the same year was appointed one of the Componitors to the Lord High Treasurer, and acceded to that position in September. In 1601 he was also made Provost of Dunbar.

In England

Upon James's accession as James I of England in 1603, Home accompanied his sovereign to Westminster, where he became Chancellor of the Exchequer (and ex officio the Second Lord of the Treasury) from 1603 to 1606. In 1603 he was also appointed to the Privy Council of England, and on 1 June that year received a grant as Keeper of the Great Wardrobe for life. On 7 July 1604 he was created Baron Hume of Berwick in the Peerage of England. In 1605 he was appointed a Knight of the Garter, and on 3 July was created Earl of Dunbar in the Peerage of Scotland. There is evidence that he took a part in the interrogation of Guy Fawkes in the immediate aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Queen Elizabeth's jewels and clothes

King James quickly disposed of much of Queen Elizabeth's jewellery, either by selling it, having it remade, or exchanging it for new pieces. George Home was involved in examing the old queen's jewels which were brought to Hampton Court at Christmas time 1603 by Sir Thomas Knyvett. The King, Home, Roger Aston and the Earl of Nottingham selected pirces for disposal and sent them to the goldsmiths John Spilman and William Herrick, including a remarkable clock in the form of glass woman studded with rubies emerals and pearls. Other pieces were sent to Peter Vanlore in exchange for a new jewel including a large rectangular ruby and two lozenge diamonds.[15] Spilman and Herrick also valued jewels that had been kept by Mary Radcliffe for the queen's immediate use.[16]

In July 1606 the earl's office of keeper of the wardrobe in Scotland was given to Sir James Hay, then a gentleman of the king's bedchamber. Dunbar was receipted for jewels held in the Tower of London and elsewhere, including; the ruby and chain from the (dismantled) pendant called the "Great H of Scotland", a hat badge with the monogram "J.A.R" in diamonds with three pendant pearls, a gold ring with five diamonds and clasped hands called the "espousal ring of Denmark", a band for hat with 23 links including six pieces with letters made of diamonds, and a diamond cross, which had been brought from Scotland for their value and significance.[17]

Sir Charles Stanhope recorded an anecdote that the Earl of Dunbar had made £60,000 from sales of clothes from the wardrobe of Queen Elizabeth I of England, and spent £20,000 on the house he built on the site of Berwick Castle.[18] A similar story was recorded by Symonds D'Ewes on 21 January 1620, that King James had given the late queen's wardrobe to the Earl of Dunbar, who had exported it to the Low Countries and sold it for £100,000.[19]

Mansion at Berwick

His house at Berwick was never finished but was widely rumoured to be magnificent. George Chaworth wrote to the Earl of Shrewsbury in 1607 about the various reports of its size, height, views, and good proportions and that its long gallery would make that at Worksop Manor look like a garret or attic. Worksop had been built by Shrewsbury's father.[20]

Landed interests

Of these, on 27 September 1603 Home received the manor and castle of Norham, with its fishing rights on the River Tweed. On 12 December a Royal Charter gave him the custody and captaincy of the Castle of St Andrews. In July 1605 he had a confirmation of all the lands previously granted to him incorporated and combined into a free earldom, Lordship of Parliament, and Barony of Dunbar.

Religious affairs

In 1608, Home journeyed to Scotland with George Abbot to arrange to promote the Episcopal Church, and to seek some sort of union between the Church of England and Church of Scotland. King James was pleased with the initial results, although the hoped-for Union never occurred and the gulf between the King and the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland widened. In July 1605 some nineteen ministers assembled at Aberdeen in defiance of the King's prohibition against the General Assembly meeting. Six of them were subsequently imprisoned in Blackness Castle near Linlithgow, and there, on 10 January 1606, the Earl of Dunbar came from London to be present at their trial and to act as the assessor. Everything was done that could be done by him to win a verdict for the King against the six ministers and it is said that he "brought plenty of money with him to purchase a verdict". In addition, the Earl himself selected the 15 jurymen, five of whom were Homes, his relatives. But even then the jury could not agree. In the end it was a majority verdict of nine against six in favour of the guilty verdict. Regardless of the irregularities, the verdict stood, and established the law that it was High Treason for any minister of the Established Church to dispute the authority of the King and the Privy Council in religious matters.

Family

In 1590 he married Elizabeth Gordon, daughter of Alexander Gordon of Gight[21] and Agnes Beaton, daughter of Cardinal David Beaton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, and Marion Ogilvy.

The English ambassador Robert Bowes commented on Elizabeth's Gordon's arrival at court in June 1590. Bowes said she was the heiress of Gight, and her mother, Agnes Beaton, by now Lady Auchindoun, had brought her to court and that George Home was likely to marry her. She became a lady in waiting to Anna of Denmark. James VI and Anna of Denmark bought her an elaborate purple velvet gown with satin sleeves and skirt in November 1590, perhaps for her marriage.[22]

Their children were:

- Anne Home (d. 1621), who married Sir James Home of Whitrig (d. between 1614–1620) in 1602.[23] Their son became James Home, 3rd Earl of Home.

- Elizabeth Home, who married Theophilus Howard, 2nd Earl of Suffolk.

- A son who died in 1604.[24]

The Earl of Dunbar died in Whitehall, London, in 1611, without male issue, whereupon the earldom and the barony became dormant.

His body was embalmed, but his funeral service did not take place in Westminster until April, after which his body was placed in a lead coffin and sent to Scotland where it was buried under the floor of Dunbar parish church, midway between the font and the pulpit. A magnificent monument, said to be finer than any in Westminster Abbey, was erected in his honour, which is still the distinguishing feature of the interior of this church.

See also

References

- Thomas Thomson, James Melville Memoirs of his own life (Edinburgh, 1827), p. 372

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 478.

- HMC 5th Report: M. E. Stirling of Renton (London, 1876), p. 648 "summa prudentia et rara taciturnitas".

- James Dennistoun, Moysie's Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1830), p. 85.

- HMC 5th Report: Stirling (London, 1876), p. 648, charter of Horsley.

- John Maitland Thomson, Register of the Great Seal: 1580-1593 (Edinburgh, 1888), pp. 715-6.

- Jemma Field, 'Dressing a Queen: The Wardrobe of Anna of Denmark at the Scottish Court of King James VI, 1590–1603', The Court Historian, 24:2 (2019), p. 154.

- George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, vol. 22 (Edinburgh, 1903), pp. 153, 199, 232.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 819, 821.

- Thomas Thomson, The historie and life of King James the Sext (Edinburgh, 1825), p. 260.

- Annie I. Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 230-1.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1882), p. 145.: National Records of Scotland E35/13.

- Robert Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials (Edinburgh, 1833), pp. 399-400.

- John Duncan Mackie, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1597-1603, vol. 13 (Edinburgh, 1969), pp. 720, 722-3.

- Thomas Rymer, Foedera, vol. 16 (London, 1715), pp. 564-5.

- Mary Anne Everett Green, Calendar State Papers James I: 1603-1610 (London, 1857), p. 66 citing TNA SP14/6/9.

- Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), pp. 327-330: Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1816), pp. 207-8.

- G. P. V. Akrigg, 'The Curious Marginalia of Charles, Second Lord Stanhope', in James G. McManaway, Giles E. Dawson, and Edwin E. Willoughby ed., Joseph Quincy Adams Memorial Studies (FSL, Washington, 1948), pp. 785-801, p. 794 noted only: Lawrence Stone, The Crisis of the Aristocracy (Oxford, 1965), p. 563 fn. 2.

- Janet Arnold, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd (London, 1988), p. 174: Maria Hayward, Stuart Style (Yale, 2020), p. 55.

- Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 3 (London, 1838), pp. 214-5

- Some sources call this laird of Gight "George Gordon", see Duncan Forbes,Ane account of the familie of Innes (Aberdeen, 1864), p. 248.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1589-1593, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 335, TNA SP52/45/229: National Records of Scotland E35/13.

- John Duncan Mackie, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 13 part 2 (Edinburgh, 1969), p. 1029 no. 836.

- Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 3 (London, 1838), p. 98.

- George Home, Earl of Dunbar, three lectures by the Reverend J Kirk, MC, CF, (Minister of Dunbar Parish Church 1913-1918), Edinburgh, 1918.

- MSS of Colonel Mordaunt-Hay of Duns Castle, Historical Manuscripts Commission, collection no. 5, 1909, page 66, number 180. His lordship is cited as deceased, and although the daughters are mentioned, there is nothing to indicate either of them assuming the peerage.

- The Complete Peerage by G. E. Cockayne, revised & enlarged by the Hon. Vicary Gibbs, edited by H. Arthur Doubleday, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, vol.vi, London, 1926, pp. 510–11.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Fortescue |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1603–1606 |

Succeeded by Sir Julius Caesar |

| Vacant Title last held by The 3rd Earl of Cumberland |

Lord Lieutenant of Cumberland, Northumberland, and Westmorland jointly with The 4th Earl of Cumberland The Earl of Suffolk Lord de Clifford 1607–1611 |

Succeeded by The 4th Earl of Cumberland The Earl of Suffolk Lord de Clifford |

.svg.png.webp)