Gilbert R. Spalding

"Dr." Gilbert Reynolds Spalding, sometimes spelled Spaulding, (14 January 1812 – 6 April 1880) was an American showman, circus owner and innovator, being the first to own his own showboat, constructed the first showboat to contain an entire circus and in 1856 the first to send an entire circus on tour in its own railroad cars.

Early life

Spalding was born in Coeymans in Albany County, New York, the son of Nancy Reynolds Spalding (1793–1862) and Guy Carleton Spalding (1780–1854). In 1838 he married Cornelia Waldron (1822–1880). Their children were: Fanny Josephine Spalding (1840–1847); Charles Alfred Spalding (1842–1930), and Henry Waldron Spalding (1844–1874). He became known as "Doc" Spalding because he owned a drug and paint store at the corner of Lydius and Pearl Streets in Albany from 1840 to 1846.[1][2]

Spalding's North American Circus

In about 1843 he accepted the circus belonging to Sam H. Nichols as security for a loan, allowing it to continue under Nichols' management until Spalding, realising he would not recoup his money as Nichols was doing bad business, visited the circus intending to bring it to Albany to sell it. However, finding that he enjoyed the circus life and that his temporary management was successful he decided to keep it as Spalding's North American Circus. In 1844 Spalding was carrying a ninety-foot tent around and had several stands at which people were turned away after 2,000 tickets were sold.[3] In 1845 his circus was touring in Canada[4] and during the 1847-48 season it was in New Orleans before moving up to the Mississippi River. Billed at this time as "The largest in the world. 200 men and horses! With all the appurtenances of corresponding extent and grandeur",[5] on arriving at St. Louis Spalding divided his show into two, managing one himself and sending the other on the road under Col. Van Orden, Spalding's brother-in-law, as manager. This second company featured the clown Dan Rice as a star turn. Spalding chartered a steamboat called the Allegheny Mail and Rice's company cruised on the Ohio, Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, but the company was forced to disband in the winter of 1848-49 owing to an outbreak of cholera. In 1847 the celebrated British equestrienne Marie Macarte appeared with the circus, while the tight-rope walker James McFarland also performed with Spalding (1844–1849) and later with Spalding and Rogers (1848–1851),[6][7] as did the ‘Shakespearean clown’ John Hodges.[8]

Spalding & Rogers

In 1848 Spalding formed a partnership with the English circus-rider Charles J. Rogers (1817-95), who had joined the circus as a performer the previous year,[9] to form the Spalding and Rogers Circus. Dan Rice again lead another land tour in 1849, travelling with his company by wagon until the end of the year, when the company reverted to Spalding.[1]

At this time Spalding & Rogers originated various innovations that later became standard, including in about 1850 the first use by a circus big top of tent quarter poles (between the center and side poles), the pipe organ, knockdown seats and using oil lamps instead of candles to light his tent.[10] In addition, theirs was the first to transport an entire circus by railroad. Another innovation was the Appollonicon, a 'Great Musical Chariot' or large bandwagon used for parades which was drawn by 40 cream-colored horses, four abreast but driven by one man who sat 80 feet behind the front horses holding ten reins in each hand - one for each two horses. The impressive 40-horse team was later used by Yankee Robinson in 1866, Dan Rice in 1873 and Barnum & Bailey in 1898, 1903 and 1904.[1]

The Floating Palace

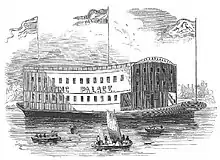

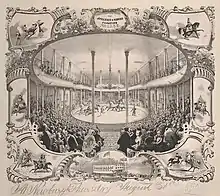

With Rogers he built The Floating Palace, an elaborate 200-foot long and sixty-foot wide two-story showboat launched in Cincinnati in May 1852 that toured the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. One of the largest showboats ever built, The Floating Palace contained a full-size circus ring for large-scale equestrian spectacles.[7]

The Floating Palace cost $42,000 to build and had 3,400 seats on two decks and was double the size of the St. James Theatre in New Orleans, at that time the city’s largest building and in which city the boat wintered for several years. The showboat's large amphitheatre had 1,000 seats on the main deck, 1,500 seats in the family circle and 900 segregated seats for its African-American audience. In addition to the 42-foot circus ring area, The Floating Palace also contained a museum with "100,000 curiosities of past years".[11] The showboat was decorated with ornate mirrors, thick carpets and hand-carved woodwork. It had 200 gas jets for lighting the circus ring for its equestrian acts and also put on minstrel shows and theatrical performances. The Floating Palace was tugged by a towboat named the James Raymond that had a steam engine which provided heat and the gas supply for illumination as well as providing sleeping quarters for 50 performers and crew.[12][13]

The showboat employed over 100 people, including ship's crew, animal trainers, performers and front-of-house staff. It had facilities for the care of the animals and printed its own daily newspaper. The outbreak of the Civil War left The Floating Palace stranded in New Orleans where it was confiscated by the Confederate Forces in 1862 for use as a hospital ship. Undeterred, Spalding chartered a smaller steamboat which he renamed Dan Castello’s Great Show after a popular Southern clown and with the circus band playing 'Dixie' as required the company made its way back to the North.[12]

Spalding, Rogers & Bidwell

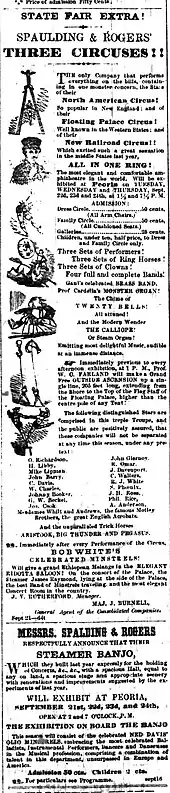

In 1856 Spalding and Rogers launched the steamer Banjo "expressly for the holding of Concerts, &c., &c., with a spacious Hall, equal to any on land, a spacious stage and appropriate scenery with renovations and improvements suggested by the experiments of last year." In the same year with their new co-partner David Bidwell, whose previous career had been in restaurants and on boats,[2] they took a ten year lease of the Pelican Theatre in New Orleans, renovating and redecorating it so that it could be used as either a circus or a theatre. It was renamed Spalding & Rogers Amphitheatre, which later again was changed to the Academy of Music. During the next few years Spalding & Rogers had two and sometimes three companies touring the USA and Canada, traveling by wagons, water and railroad, becoming the first circus to use the latter method of transportation for an entire circus.

In 1860 Spalding and Rogers took a three-year lease on the Old Bowery in New York which they renovated and fitted with a movable stage so as to be able to cater for both equestrian and dramatic performances. Among their acts were the trapeze artists François and Auguste Siegrist and the tight-rope dancer Marietta Zanfretta.[14] In January 1861 they staged the spectacular Tippoo Sahib, or, the Storming of Seringapatam with many trick transformations including a vast enemy encampment, an Indian jungle near the Taj Mahal and a bombardment by British forces with a charge on foot and horse.[15]

From there they transferred to The Boston Theatre (then known as the Academy of Music), where they played a highly successful engagement of some weeks' duration. After their experience with The Floating Palace early in 1862, Spalding and Rogers decided to avoid the Civil War altogether.[16][17] In Spring of that year they constructed a magnificent portable amphitheatre upon an entirely new plan, the brigantine Hannah was purchased and fitted with accommodations for a circus company, and the next two years were passed in tours of Brazil, Uruguay, Buenos Aires and the West Indies. On the return voyage the vessel was wrecked at Long Branch, New Jersey, the people and horses, together with some of the baggage, being saved, but the amphitheatre, wardrobe, properties and vessel were lost. Despite this disaster, the venture was a great financial success, and it is said that more honors were bestowed upon the company than had been received by any other similar troupe in a foreign land. On their return to the United States in 1864, Spalding & Rogers took their circus to the newly built Hippotheatron in New York, where they opened for four weeks on 25 April 1864. During their stay a new roof was built and their company left on May 21.[18]

In 1866 Spalding and Rogers dissolved their partnership, and Rogers retired from professional life and went to reside near Philadelphia. The co-partnership between Spalding and Bidwell continuing, shortly afterwards they leased and rebuilt the Olympic Theatre in St. Louis. Having already the Academy of Music in New Orleans they leased theatres in Mobile, Alabama, and Memphis, Tennessee, and established a theatrical circuit, which they conducted successfully for a few seasons, Thomas B. MacDonough being associated with them in a managerial capacity, and the firm being named Spalding, Bidwell & MacDonough.[19]

In 1867 a scheme was devised to send an American circus company to Paris in France, to perform during the Paris Exposition. The manager and backers of the company were Avery Smith, Gerard C. Quick, John J. Nathans, Dr. G.R. Spalding and David Bidwell. An edifice in which they were to have performed was built for the purpose of wood with a canvas top. It had forty-four private-boxes, an imperial loge, seven hundred and sixty parquet seats, fourteen hundred and twenty balcony seats, and a gallery capable of accommodating nearly two thousand persons, the seats being all cane-bottom chairs. Col. Van Orden had been sent in advance to Paris to prepare the way for the company, which was very strong. The chief attractions, according to the files of the New York Clipper, included James Robinson and his son Clarence, Frank Pastor, Robert Stickney, G M. Kelly, Lorenzo Maya, the Rollande Brothers, William Conrad, Charles Rivers, the performing horse Hiram, a performing buffalo, and a troupe of Indians. Most of the company and all the stock, consisting of twenty-three horses, two mules, and a buffalo, also four horses belonging to James Robinson, left New York in the steamship Guiding Star on March 30 1867, David Bidwell and Gerard C. Quick accompanying them. The other performers followed in steamships that sailed at later dates. After arriving in Paris, and when nearly all the preparations for their showing had been made, it was discovered that a local law prevented the erection of any wooden building within the city limits; consequently they could not use their pavilion, and, all other places being engaged, the venture was about to end in failure, when fortunately opportunity was given the American company to play for a brief time, but the result was not what had been expected.[19]

Later life

In 1872 'Dr.' Spalding again put Dan Rice on the road with a show managed by his son Harry W. Spalding, who was dangerously wounded by a pistol shot in Baxter Springs, Kansas, which was probably the cause of his death, which took place at his father's residence in Saugerties in New York on February 4 1874. 'Dr.' Spalding's last venture in the circus business was during the tenting season of 1875, when he was the principal backer of Melville, Magintey & Cooke's Centennial Circus and Thespian Company. Spalding & Bidwell dissolved their co-partnership and in the division of the property David Bidwell retained the Academy of Music, New Orleans, and Spalding the Olympic Theatre, St. Louis, which was successfully managed by his son Charles Spalding. Spalding and Bidwell formed a new co-partnership and purchased the St. Charles Theatre in New Orleans which they intended to restore to its previous position of a first-class theatre but were unable to complete this plan owing to Spalding's death.[19]

Gilbert R. Spalding died of consumption aged 68 in New Orleans in 1880 and his body was removed to his home at Saugerties. He was buried in the Spalding and Robbins family plot in Albany Rural Cemetery.[20][21] Spalding left a widow and one surviving son, Charles Spalding. Besides Harry W. Spalding, whose death is referred to above, there had been a daughter who died when quite young.[19]

References

- William L. Slout, Olympians of the Sawdust Circle: A Biographical Dictionary of the 19th-Century American Circus, The Borgo Press (1998) - Google Books p. 281-282

- Gillian M Rodger, Champagne Charlie and Pretty Jemima: Variety Theater in the Nineteenth Century, University of Illinois Press (2010) - Google Books p. 77

- Notes on the History of Circus Tents - Circus Historical Society

- Spalding's North American Circus (1845) - Circus Ontario website

- Spalding's Monster North American Circus (1847) - William & Mary Libraries - William & Mary Law School

- Slout, Olympians of the Sawdust Circle, p.189

- Gilbert R. Spalding - The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press

- Rice, Edward L., Monarchs of Minstrelsy, 1910

- William L. Slout, Clowns and Cannons: The American Circus During the Civil War, Emeritus Enterprise Book (2000) - Google Books p. 41

- Gilbert R. Spaulding: American circus impresario - Encyclopædia Britannica

- Leavitt, P., & Moy, J. Spalding and Rogers' Floating Palace, 1852–1859. Theatre Survey, (1984), 25(1), pp. 15-27

- The Floating Palace - New Orleans Nostalgia: Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions - New Orleans Bar Association

- Carolyn M. Bowers and Linda A. Fisher, Agnes Lake Hickok: Queen of the Circus, Wife of a Legend, University of Oklahoma Press (2007) - Google Books p. 64

- Slout, Clowns and Cannons, p. 43

- Slout, Clowns and Cannons, p. 45

- Philip A. Loring, 'The Most Resilient Show on Earth: The Circus as a Model for Viewing Identity, Change, and Chaos', Ecology and Society, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Jun 2007) p. 2

- Fox, C. P., and T. Parkinson. 1969. 'The Circus in America', Country Beautiful, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA (1969)

- T. Allston Brown, A History of the New York Stage, Vol. 2, New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc., 1903, pp. 353-356

- Obituary for 'Dr' Gilbert R. Spalding - New York Clipper, New York, 17 April 1880

- Burial record for Gilbert Reynolds Spalding - Ancestry.com(subscription required)

- Gilbert Reynolds Spalding - Find a Grave