Gilmore and Pittsburgh Railroad

The Gilmore and Pittsburgh Railroad (G&P), now defunct, was an American railroad located in southwestern Montana and east-central Idaho. Constructed in 1909 and 1910 between the towns of Armstead, Montana, and Salmon, Idaho, the G&P served mining and agricultural areas in Lemhi County, Idaho, and Beaverhead County, Montana. The line was financially backed by the Northern Pacific Railway, and later became its subsidiary. Never financially successful, the G&P ceased operations in 1939, and the railroad was dismantled the following year.

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Armstead, Montana |

| Locale | Beaverhead County, Montana; Lemhi County, Idaho |

| Dates of operation | 1910–1939 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

Planning and construction

During the first decade of the 20th Century Lemhi County, in the remote Salmon River country of central Idaho, was seeing both increased agricultural development and substantial, renewed mining activity. The area was part of one of the largest contiguous blocks of land not served by a railroad at that time, and consequently there was significant interest in the prospect of building a railway line to (or through) the region. The desire for a railroad was perhaps most strongly felt by those promoting the county's mining developments, although a variety of existing railway companies also studied the prospects of the area. The Northern Pacific Railway (NP) gave Lemhi County particular attention, envisioning a new transcontinental route that would veer southward from existing NP lines in Montana, cross into Idaho via Bannock Pass, and then follow the rugged Salmon River canyon westward across the state.

These dreams began translating to action in 1907 when a group of Pennsylvania businessmen led by W. A. McCutcheon incorporated the Gilmore and Pittsburgh Railroad. McCutcheon envisioned a railroad running westward from a connection with the Oregon Short Line Railroad at Armstead, Montana. The line would enter Lemhi County via Bannock Pass, and continue to the Lemhi River valley. In the valley, branch lines would run upstream to the promising mining camp of Gilmore, and downstream to the county seat of Salmon. Soon, McCutcheon was able to interest NP officials in his plan, since a completed G&P could form a basis for a future NP line down the Salmon River. The NP assisted in the initial survey of the G&P route, and later agreed to financially and materially support the G&P's construction.

A contract for construction of the G&P grade was awarded in March, 1909, and work began in earnest the following month. Construction was pursued in earnest throughout the following year, working west from Armstead, and the tracklayers reached Salmon on April 25, 1910. The completed line was 118 miles (190 km) in length, and was largely built to the mainline standards of the NP. A golden spike celebration was held in Salmon that May 18, even though portions of the line—including the tunnel under Bannock Pass—were still being completed. Regular passenger and freight service on the G&P began soon thereafter.

Optimism and rumors concerning further expansion of the G&P persisted through 1910. McCutcheon had promised that the line would be extended northward from Armstead to Dillon, Montana that year, the first step in completing a connection to the NP's trackage at nearby Twin Bridges. No further construction took place, however, in part due to G&P legal difficulties in securing right-of-way between Armstead and Dillon. Simultaneously, though, the NP began to realize the engineering difficulties and limited economic potential of its proposed Salmon River route, and local G&P officials began to discover that the local traffic potential was actually far less than anticipated. Consequently, the hopes for future expansion of the G&P soon faded, and the line was never extended beyond either Armstead or Salmon.

Route

The route of the G&P was remote, thinly populated, and often rugged. The line began at the small hamlet of Armstead, Montana, a station stop on the Oregon Short Line Railroad's route between Idaho Falls, Idaho and Butte, Montana. (The Oregon Short Line was a long-time subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, and was later absorbed into that system.) Armstead was in a high valley of the Beaverhead River, in a region known for livestock grazing. The G&P maintained a small yard there, and it was the site of the railroad's corporate office.

From Armsted, the railway headed almost due west, traversing a thinly-populated ranching region known as Horse Prairie. The area provided additional livestock traffic for the railroad, and there were mines in the nearby mountains. Substantial areas of cut and fill were required as the railroad ascended the prairie. The railroad curved southward near the western end of Horse Prairie. and began its ascent of Bannock Pass.

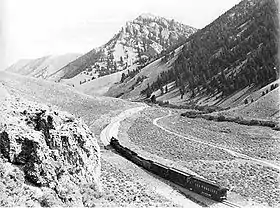

Bannock Pass, on the Idaho-Montana border and the Continental Divide, was by far the most substantial obstacle encountered by the G&P. The pass itself is at an elevation of 7,681 feet (2,341 m), some 1,800 feet (550 m) higher than the center of Horse Prairie. Temporary trackage was built over the top of the pass during the G&P's construction, but a tunnel beneath the pass was clearly needed for the railway's permanent use. Since a tunnel to completely bypass the heavy grades of the pass was prohibitively expensive, the railroad compromised by boring a shorter, 600-foot (180 m) tunnel at the 7,575-foot (2,309 m) elevation. To bring the tracks to the elevation of the tunnel, the railroad line included a switchback on each side of the summit; trains ascending the pass would pull into the first switchback, run backwards through the summit tunnel, and then reverse direction again at the switchback on the opposite side.

Descending Bannock Pass, the railroad followed a narrow canyon into Idaho's Lemhi Valley and the small agricultural community of Leadore, some 55 miles (89 km) from Armstead. The G&P's repair shops were at Leadore, and it also marked a junction point for the railway. The main line continued northwest from Leadore for another 45 miles (72 km), following the broad valley and the Lemhi River downstream through fertile farming and ranching land to the county seat of Salmon. Salmon was the line's terminus, and by far the largest town on the G&P route, with a 1910 population of 1,434.

The only branch line operated by the G&P began at Leadore and headed southeast, following the Lemhi River valley upstream about 19 miles (31 km) to the town of Gilmore, near the upper end of the valley. Gilmore in 1910 was the center of a prosperous silver and lead mining district, and was thus a major source of early traffic for the railroad.

Operating history

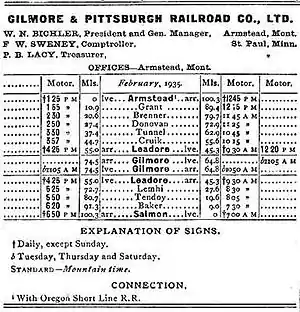

When the G&P began service in 1910 the railroad owned a total of 8 steam locomotives, 16 passenger cars, 250 freight cars, a rotary snowplow, and other miscellaneous pieces of equipment; except for some of the freight cars, all equipment was acquired second-hand. When service began that May, the G&P scheduled a tri-weekly passenger train between Armstead and Salmon, leaving Armstead on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and returning on the following days. Freight trains also operated on most days. Traffic levels proved lower than expected, however, and in 1913 the separate freight and passenger services were replaced by a tri-weekly mixed train, carrying both freight and passenger equipment.

Both passenger and freight traffic declined in later years, and beginning in 1922 mixed train service was partially supplanted by a Brill railbus, a self-propelled vehicle designed to carry passengers and small freight shipments. For most of the 1920s, the railbus operated between Salmon and Gilmore, while the tri-weekly mixed continued between Salmon and Armstead. In 1931, the G&P borrowed a second, larger railbus from the Northern Pacific, and used it to provide a daily-except-Sunday roundtrip between Armstead and Salmon. The mixed was discontinued at that time, and freight trains began operating only as required, usually about once a week.

Service on the Gilmore branch was more dependent on the output of the district's mines, and as they declined and ultimately closed rail service to Gilmore dropped correspondingly. The Gilmore branch was largely out of service by the 1930s.

The railroad's equipment roster was significantly reduced over the years, as well, because of a lack of traffic and a need to conserve expenses. The majority of the line's passenger and freight cars, and all but two of the locomotives, were gone by the early 1930s.

Operations of the railroad were directed by its President and General Manager, W. N. Bichler (1881–1955). Bichler, who lived in Armstead, managed the railroad throughout its entire corporate history, from construction to abandonment.

Decline and abandonment

Traffic levels on the G&P never began to reach the optimistic expectations of the line's backers, and by the early 1910s it was clear that they never would. The railroad's lack of economic viability was realized as early as 1913, when the G&P's substantial construction indebtedness (nearly $6,000,000) was written off by the Northern Pacific in exchange for full ownership of the line. Despite continual efforts to economize, the railroad lost money throughout much of its existence.

The railroad's prospects worsened in the 1920s, as the Gilmore mines declined and eventually closed, and in the 1930s as improved local roadways made auto traffic to and within the region easier. By the late 1930s it was clear that the G&P's days were numbered. Early in 1939 the railroad announced that it was out of money and would cease operating effective that May 1. The moribund railroad sat unused until the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the line's abandonment in 1940, and the track was removed later that year.

Remnants

While much of the physical evidence of the G&P has disappeared since the railroad's abandonment, numerous traces of the route still remain visible in the 21st Century. The line's eastern terminus at Armstead is now beneath the waters of Clark Canyon Reservoir. Elsewhere, though, most of the railroad's grade in Montana remains readily visible, as does the former alignment over Bannock Pass. Less of the old G&P grade between Leadore and Salmon is evident today, due to agricultural and highway development, as the highway is on the G&P right of way for most of the way from Leadore to Salmon. The Bannock Pass tunnel remains visible, although the bore has partially collapsed. Gilmore has long been a ghost town.

The only major G&P building to survive in 2006 is the former freight house at Leadore, A modern structure nearby (serving as the town's community center) is a replica of the former Leadore depot building. Several derelict railway cars once used on the G&P still exist on farms and ranches along the railroad's former route.