Global Certification Commission

The Global Commission for the Certification of the Eradication of Poliomyelitis (commonly known as the Global Certification Commission or GCC) was formed in 1995 by the World Health Organization (WHO) to independently verify the eradication of wild poliovirus around the world.[1] The commission has been able to certify five WHO regions as having eradicated wild poliovirus, with the Eastern Mediterranean Region being the sole remaining region yet to gain certification. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative, a related initiative begun by the WHO in 1988, has been able to reduce wild poliovirus cases by 99.99% through vaccination.

| Abbreviation | GCC |

|---|---|

| Formation | February 16, 1995 |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

Parent organization | World Health Organization |

History

The first meeting of the Global Certification Commission was convened in Geneva, Switzerland, on 16–17 February 1995.[2] The commission was initially established as a 13-person board and assigned the responsibility of delineating the criterion for verification and certification of the eradication of the wild poliovirus.[3] The World Health Assembly, the governing body of the World Health Organization, had also created the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) in 1988 with the resolution to eradicate the disease by 2000.[3] As of August 2020, the WHO partners with the Rotary International, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance while working towards the goals of the GPEI.[4]

The global eradication of wild poliovirus type 2 (WPV2) was certified in September 2015. The last detection of indigenous WPV2 was in 1999.[5][6] Indigenous wild poliovirus type 3 was last detected in 2012 and its global eradication was certified in October 2015.[7][8] Wild poliovirus type 1 is the only form of the virus that remains uninterrupted.[9]

Structure

The Global Certification Commission is the top-level decision making body of a three-tier process. Each WHO member state's national polio program appoints a National Certification Committee. These national committees meet annually to draft a report on polio surveillance and eradication. These reports are evaluated by Regional Certification Committees, expert panels appointed by the WHO with members that are independent of both the national committees and the GPEI. There are six Regional Certification Committees, one for each WHO region. The regional committees meet annually to review the reports of the national committees. The chairs of the six regional committees comprise the Global Certification Commission. They meet irregularly as needed for global decision making.[10]

Regional certification

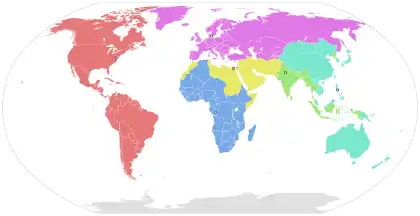

| Africa Americas | Eastern Mediterranean Europe | South East Asia Western Pacific |

By 1994, the disease had been certified to be eradicated in the Americas, one of the six WHO-designated regions.[3] The Western Pacific region was certified in 2000. From these early experiences, the WHO established a criterion for certification: three years of no new detection of wild poliovirus in the face of strict surveillance, where surveillance is further defined as the finding and examination of at least one case of nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis per 100,000 children under 15 years old – implying that wild poliovirus would be detected if in existence in the country or region.[3][11]

With the criteria established, the commission resolved to certify each of the remaining regions until the disease was eradicated globally.[3] The European Region was certified in 2004 and the South-East Asia Region in 2014.[12]

In 1996, African nations signed the Yaoundé Declaration on Polio Eradication in Africa, and Nelson Mandela started the "Kick Polio out of Africa" campaign. The WHO regional director for Africa appointed 16 people to the Africa Regional Certification Commission (ARCC) in 1998.[13] Based in Yaoundé, Cameroon, and led by Rose Leke as chairperson as of 2020,[14][15] the group was tasked with overseeing the eradication effort in the Africa WHO region.[13] The independent body is the only organisation recognized to certify that polio has been eradicated from the region.[16] On 25 August 2020, the ARCC declared that wild poliovirus has been eliminated in its region which includes 47 countries spanning most of Africa.[13][17] The last reported case of polio in the region was on 21 August 2016, in Borno, Nigeria.[11][15] Among the conditions for certification of the region was a requirement that 95% of the population be immunised.[18]

Cases of polio have seen an 99.99% decline globally since the start of the polio eradication initiative:[19] "From 350 000 cases annually in 125 countries in 1988, to 102 cases in two countries in 2020 as of [August] 19."[13] The Eastern Mediterranean Region is the only WHO region that has yet to be certified as having eradicated wild poliovirus.[20] The region includes 22 countries spanning from Morocco to Pakistan,[21] several of which have individually eradicated the disease. This region experiences significant political unrest, humanitarian crises, forced displacement, and deterioration of health care systems, which cripple eradication efforts.[22]

Syria, Yemen, and Somalia are categorized as very-high-risk, and Iraq, Sudan, and Libya are categorized as high-risk, while Pakistan and Afghanistan are the only countries in which the disease remains endemic as of 2019.[22] Since 2007, people administering polio vaccines have been the target of violence in Pakistan.[23] A 2011 US Central Intelligence Agency operation used a hepatitis vaccination program as a cover to search DNA evidence to confirm the location of Osama bin Laden.[24][23] Following his killing the same year, Islamist insurgents in the region have become more hostile to vaccination efforts. More recently, the hostility has been exasperated by the United States' expansion of the use of drone strikes in northwest Pakistan;[23] in June 2012, Mullah Nazir, leader of the Federally Administered Tribal Agencies, distributed leaflets calling for a ban on polio vaccination with the goal of persuading the US to stop drone strikes in the area.[25]

References

- Hecht, Alan (2009). Polio. Infobase Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4381-0161-3.

- "Report of the 1st Meeting of the Global Commission for the Certification of the Eradication of Poliomyelitis" (PDF). WHO.int. World Health Organization. 1995. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Technical Consultative Group to the World Health Organization on the Global Eradication of Poliomyelitis (1 January 2002). ""Endgame" Issues for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 34 (1): 72–77. doi:10.1086/338262. ISSN 1058-4838.

- "Global polio eradication initiative applauds WHO African region for wild polio-free certification". WHO.int (Press release). World Health Organization. 25 August 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Previsani, Nicoletta; et al. (23 June 2017). "Progress Toward Containment of Poliovirus Type 2 – Worldwide, 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (24): 649–652. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6624a5. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 5657795. PMID 28640795.

- "Global eradication of wild poliovirus type 2 declared". PolioEradication.org. Global Polio Eradication Initiative. 20 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Cochi, Stephen L.; Pallansch, Mark A. (5 July 2020). "The Long and Winding Road to Eradicate Vaccine-Related Polioviruses". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa393.

- "Two out of three wild poliovirus strains eradicated". PolioEradication.org. Global Polio Eradication Initiative. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Chard, Anna N.; et al. (26 June 2020). "Progress Toward Polio Eradication – Worldwide, January 2018 – March 2020". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (25): 784–789. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a4. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 7316320. PMID 32584798.

- Datta, S. Deblina; et al. (July 2017). "National, Regional and Global Certification Bodies for Polio Eradication: A Framework for Verifying Measles Elimination". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 216 (1): S351–S354. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw578.

- Umeh, Gregory C.; et al. (13 December 2018). "Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance intensification for polio certification in Kaduna state, Nigeria: lessons learnt, 2015–2016". BMC Public Health. 18 (Suppl 4). doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6186-y. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6291918. PMID 30541509.

- Bahl, Sunil; et al. (1 February 2018). "Global Polio Eradication – Way Ahead". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 85 (2): 124–131. doi:10.1007/s12098-017-2586-8. ISSN 0973-7693. PMC 5775388. PMID 29302865.

- Africa Regional Certification Commission (1 October 2020). "Certifying the interruption of wild poliovirus transmission in the WHO African region on the turbulent journey to a polio-free world". The Lancet Global Health. 8 (10): e1345–e1351. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30382-X. ISSN 2214-109X.

- "'Momentous milestone' as Africa eradicates wild poliovirus". UN News. 25 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Allison, Simon (25 August 2020). "Good news: Africa is declared free of wild polio". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Pai, Bilkisu Halilu (18 June 2018). "Africa Regional Certification Commission meeting begins in Abuja". Voice of Nigeria. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Annuncio storico dell'Oms: "L'Africa è libera dalla polio"". La Repubblica (in Italian). 25 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Scherbel-Ball, Naomi (25 August 2020). "Africa declared free of polio". BBC News. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Lickness, Jacquelyn S.; et al. (2020). "Surveillance to Track Progress Toward Polio Eradication – Worldwide, 2018–2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6920a3. ISSN 0149-2195.

- Abbany, Zulfikar (25 August 2020). "Polio eradication in Africa points to challenges ahead". DW. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Turk-Adawi, Karam; et al. (February 2018). "Cardiovascular disease in the Eastern Mediterranean region: epidemiology and risk factor burden". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 15 (2): 106–119. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2017.138. ISSN 1759-5010. PMID 28933782.

- Al Gunaid, Magid; et al. (29 October 2019). "A Collaborative Initiative to Strengthen Sustainable Public Health Capacity for Polio Eradication and Routine Immunization Activities in the Eastern Mediterranean Region". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 5 (4). doi:10.2196/14664. ISSN 2369-2960. PMC 6913771. PMID 31663863.

- Kennedy, Jonathan; et al. (30 September 2015). "Islamist insurgency and the war against polio: a cross-national analysis of the political determinants of polio". Globalization and Health. 11. doi:10.1186/s12992-015-0123-y. ISSN 1744-8603. PMC 4589183. PMID 26420386.

In the past few years, Islamist insurgency has had a strong effect on where polio cases occur. This is because Islamist insurgents deliberately undermine the efficacy of immunization campaigns by spreading misinformation and attacking polio workers. The evidence for all types of non-Islamist insurgency is less compelling. First, in some cases the relationship is no longer significant when we control for variables that operationalize the level of development in a country. This suggests that the relationship is spurious.

- "Polio eradication: the CIA and their unintended victims". The Lancet. 383 (9932): 1862. 31 May 2014. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60900-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 24881975.

- Boone, Jon (26 June 2012). "Taliban leader bans polio vaccinations in protest at drone strikes". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 October 2020.