Glovers Harbour, Newfoundland and Labrador

Glovers Harbour (/ˈɡloʊ.vərz/ GLOH-verz[10][11]), also written as Glover's and formerly known as Thimble Tickle(s), is an unincorporated community and harbour in Notre Dame Bay, on the northern coast of Newfoundland, Canada.[5][6][12][8] It is delineated as a designated place for statistical purposes.

Glovers Harbour

Thimble Tickle | |

|---|---|

Welcome sign referencing the giant squid specimen of 1878 and its recognition by Guinness World Records | |

| |

Glovers Harbour Location within Newfoundland  Glovers Harbour Location within Canada | |

| Coordinates: 49°27′13″N 55°28′55″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Electoral district | Coast of Bays—Central—Notre Dame (federal)[1] Exploits (provincial)[2][3] |

| Census division | 8 (subdivision E)[4] |

| Settled | late 1800s[5] (≤1878) |

| Founded by | Joseph Martin[5] |

| Named for | John Hawley Glover[5] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.85 km2 (3.42 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–20 m (0–66 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 92 |

| • Density | 10.4/km2 (27/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−03:30 (NST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−02:30 (NDT) |

| Postal code | A0H 1E0[7] |

| Area code | 709 (COC: 483)[7] |

| NTS map no. | 002E06[8] |

| GNBC code | AAIAE[8] |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

Settled sometime in the second half of the 19th century, Glovers Harbour has remained primarily a fishing village throughout its history. It is best known for the giant squid that was captured on its shores in 1878, which was subsequently recognised as a world record by Guinness. Glovers Harbour brands itself as the "home of the giant squid" and has a small heritage centre and "life-sized" sculpture dedicated to the animal, these being its main tourist attractions.

Etymology and geography

The settlement was named after John Hawley Glover, who served as the Governor of Newfoundland in 1876–1881 and again in 1883–1885.[5][13] A promontory on the southern shore of Glovers Harbour is known as Glovers Point.[12][14] Glovers Harbour also gives its name to the Glovers Harbour Formation, a sequence of volcanic rocks of the Wild Bight Group that lie to its west.[15][16] Other geographical points of interest include an unmarked trail called Rowsell's Trail.[13]

Thimble Tickle

Glovers Harbour was formerly known as Thimble Tickle(s).[11][17][18] In Newfoundland English, a tickle is a narrow strait (see List of tickles). The name Thimble Tickle (and variants thereof) has been applied to a number of related geographical features. The Gazetteer of Canada of 1968 lists Thimble Tickles (a series of channels), Thimble Head, and Thimble Tickle Head (both headlands) as features in the same general area.[12] Other associated geographical names include Cumlins Cove and Cumlins Head, both listed by the Gazetteer as features of Thimble Tickle(s).[12] According to the Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, Thimble Tickles is a "scattered group of islands" in the vicinity of Glovers Harbour.[5]

Thimble Tickle Prospect, also known as the Lockport Mine (after Lockport), was a copper and sulfur mine located "over the hill" and just west of Glovers Harbour.[17][16] It operated intermittently in the 1880s and 1890s; the shafts were sealed around 1999.[17]

History

.jpg.webp)

Early years

According to local tradition, Glovers Harbour was founded by Joseph Martin, originally of Harbour Grace,[lower-alpha 1] who settled there sometime in the late 1800s.[5][13] Martin's daughter married the son of George Marsh, the first permanent settler of nearby Winter House Cove, and the two families remained the main inhabitants of Glovers Harbour until the arrival of Alex Boone, previously of Cottrell's Cove.[5]

Glovers Harbour first appeared in the Canadian national census of 1901, under the name Glover Harbor, when its population was recorded as 67, though this included the inhabitants of Leading Tickles and Lock's Harbour (later Lockesport(e) or Lockport[17]).[5][20] In the 1911 census, it was listed as Glover's Harbor, with a population of 28 Newfoundland-born residents, predominantly followers of the Church of England, though one Methodist was also recorded.[5][21] The population fell to a low of 11 at the time of the 1921 census[22][23] but rebounded to 29 in 1935[24][25] and 38 in 1945.[26][27]

Resettlement period

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901[20] | 67* | — |

| 1911[21] | 28 | — |

| 1921[22][23] | 11 | −60.7% |

| 1935[24][25] | 29 | +163.6% |

| 1945[26][27] | 38 | +31.0% |

| 1966[5] | 52 | +36.8% |

| 1971[5] | 145 | +178.8% |

| 1981[5] | 136 | −6.2% |

| 1991[28] | 122 | −10.3% |

| 1996[28] | 121 | −0.8% |

| 2001[29] | 112 | −7.4% |

| 2006[30] | 93 | −17.0% |

| 2011§[6] | 78 | −16.1% |

| 2016[6] | 92 | +17.9% |

| * Included inhabitants of Leading Tickles and Lock's Harbour.[5] § Population initially reported as 71[31] but later revised to 78.[6][32] | ||

From its founding, small-scale inshore cod fishing was the mainstay of the local economy, supplemented by seasonal work such as logging as well as livestock and vegetable farming.[5][13] By the middle of the 20th century, however, a lack of transport infrastructure left the isolated residents of Glovers Harbour with few other job opportunities.[5] The 1962 construction of a road connecting Glovers Harbour to Route 350 was transformative, as it opened access to the commercially important town of Botwood and to the nearby fish markets of Leading Tickles and Point Leamington.[5][13] Movement of people from more isolated nearby communities to Glovers Harbour soon followed, largely motivated by a Newfoundland-wide government resettlement program, though some early moves occurred without government assistance.[5][13]

Despite being larger at the time, the neighbouring communities of Lockesporte and Winter House Cove (both located in Seal Bay) were never connected to the road network owing to the difficulty of the surrounding terrain, and this contributed to their rapid decline and eventual abandonment by the close of the 1960s.[17][33][34] As recorded in the 1971 census, eight families totalling 39 people (predominantly with the surname Haggett) had moved to Glovers Harbour from Lockesporte alone.[5][lower-alpha 2] At least four families (Burton, followed by Goudie, Haggett, and Rowsell) had similarly resettled from Winter House Cove by this point.[5] As a result, the population of Glovers Harbour swelled almost threefold between 1966 and 1971, from 52 to 145.[5]

The concomitant demographic changes turned Glovers Harbour into "a predominantly Salvation Army community".[5][13] The village's first Salvation Army citadel—which also served Lockesporte, Ward's Point, and Winter House Cove, and doubled up as a school—was erected on land belonging to Electra Martin.[5] This was followed by a second citadel, originally constructed near Flag Pond around 1942, that was later moved close to Glovers Harbour Road.[5]

During resettlement, Winter House Cove's Anglican church—a school chapel first recorded in the 1901 census—was floated (transported over water) to Glovers Harbour, where it found use as a school until the late 1960s.[5] Both this school and another one that had been built in Glovers Harbour by the 1960s were later closed; thereafter, students attended elementary school in Leading Tickles and high school in Point Leamington, which were reached by school bus.[5] The Anglican church was subsequently renovated and held fortnightly services presided over by a visiting minister from Botwood.[5]

From its peak following resettlement, the population of Glovers Harbour dropped to 136 by 1981[5] and continued to gradually contract over the next three decades.[28][29][30][31]

Current status

As of 2016, Glovers Harbour had a population of 92, an increase of 17.9% from the 78 inhabitants recorded in the 2011 census.[6] The 2016 census recorded 120 private dwellings, of which 39 were occupied by usual residents, with a median value of CA$100,161.[6] The median total household income was CA$61,824.[6]

Over time, the fishery in Glovers Harbour has diversified to encompass lobster, capelin, squid, and queen crab (also known as snow crab).[13] In 1997, a proposal was submitted to recognise the coastal area around Leading Tickles and Glovers Harbour as a Marine Protected Area (MPA).[35] On 8 June 2001, the area officially came under consideration to become an MPA when it was identified as an Area of Interest by the minister for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO).[35]

Giant squid

Thimble Tickle specimen

Glovers Harbour is best known for its association with the giant squid (Architeuthis dux).[13] On 2 November 1878, a live animal reportedly 55 ft (16.8 m) long, which came to be known as the "Thimble Tickle specimen", was found aground offshore.[36][37][38][39] It was secured to a tree with a grapnel and rope and died as the tide receded. No parts of the animal were saved and no photographs or exact measurements exist as the specimen was cut up for dog food soon after its discovery; all that is known of it comes from a second-hand account by Reverend Moses Harvey in a letter to the Boston Traveller dated 30 January 1879, which was reproduced in the works of Yale zoologist Addison Emery Verrill the following year:[36][37]

On the 2d day of November last, Stephen Sherring, a fisherman residing in Thimble Tickle, not far from the locality where the other devil-fish [the "Three Arms specimen"], was cast ashore, was out in a boat with two other men; not far from the shore they observed some bulky object, and, supposing it might be part of a wreck, they rowed toward it, and, to their horror, found themselves close to a huge fish, having large glassy eyes, which was making desperate efforts to escape, and churning the water into foam by the motion of its immense arms and tail. It was aground and the tide was ebbing. From the funnel at the back of its head it was ejecting large volumes of water, this being its method of moving backward, the force of the stream, by the reaction of the surrounding medium, driving it in the required direction. At times the water from the siphon was black as ink.

Finding the monster partially disabled, the fishermen plucked up courage and ventured near enough to throw the grapnel of their boat, the sharp flukes of which, having barbed points, sunk into the soft body. To the grapnel they had attached a stout rope which they had carried ashore and tied to a tree, so as to prevent the fish from going out with the tide. It was a happy thought, for the devil fish found himself effectually moored to the shore. His struggles were terrific as he flung his ten arms about in dying agony. The fishermen took care to keep a respectful distance from the long tentacles, which ever and anon darted out like great tongues from the central mass. At length it became exhausted, and as the water receded it expired.

The fishermen, alas! knowing no better, proceeded to convert it into dog's meat. It was a splendid specimen—the largest yet taken—the body measuring 20 feet [6.1 m] from the beak to the extremity of the tail. It was thus exactly double the size of the New York specimen [better known as the "Catalina specimen"], and five feet [1.5 m] longer than the one taken by [fisherman William] Budgell [the "Three Arms specimen"]. The circumference of the body is not stated, but one of the arms measured 35 feet [10.7 m]. This must have been a tentacle.

.jpg.webp)

Though the original account mentions only Stephen Sherring and two other (unnamed) fishermen,[36][37] later sources identify Glovers Harbour's founder, Joseph Martin, as one of the fishermen involved in the squid's capture.[17][18][40] George Marsh and Henry Rowsell—the founders of Winter House Cove and Lock's Harbour (Lockesporte), respectively—have also been suggested as participants.[17] The fishermen may have learned of Moses Harvey's interest in the giant squid when the latter visited Notre Dame Bay only a couple of months earlier, in August 1878, as part of a geological survey.[18] A CBC News report broadcast in 2004 features Maurice Martin, great-great-grandson of Joseph Martin, recounting the story of the squid's capture as told to him by his grandfather.[10]

The "Thimble Tickle specimen" has long been recognised by Guinness World Records and its prior incarnations as the largest giant squid ever recorded.[41][42][43] However, the reported measurements—particularly the length of the "body [..] from the beak to the extremity of the tail" (i.e. mantle plus head) at 20 ft (6.1 m), but also the total length of 55 ft (16.8 m)—greatly exceed all modern, scientifically verified records, which encompass several hundred specimens.[44][45][46][47] Such lengths are now generally regarded as exaggerations and often attributed to artificial lengthening of the two long feeding tentacles (analogous to stretching elastic bands) or to inadequate measurement methods such as pacing.[44][45][48] Over time, various other superlative measurements have been attributed to the specimen, including a mass of 2 tonnes (4,400 lb) and an eye diameter of 40 cm (16 in).[18][49]

Giant Squid Interpretation Site

Today, a small heritage centre and a "life-sized", 55-foot sculpture—collectively known as the Giant Squid Interpretation Site—stand near the site of the specimen's capture[10][50] and are the community's main tourist attractions.[13][51] The sculpture was completed in 2001 following a CA$100,000 government contribution; ten thousand visitors were expected in the first year.[10][52] It weighs four tonnes and was constructed from a combination of steel, wire mesh, and concrete.[10][52][53] The sculpture was designed by fine arts teacher Don Foulds of Saskatoon[lower-alpha 3] and built by him and his students, with help from Jason Hussey, Niel McLellan, and Edward O'Neill.[10][52] It featured on a Canada Post stamp issued in 2011 as part of the "Roadside Attractions" series, with a print run of 1,045,000.[52][54] The heritage centre opened in 2009 and includes a small museum, gift shop, and picnic area.[50][51]

- Thimble Tickle giant squid of 1878

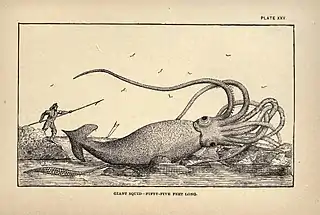

Artist's impression of the Thimble Tickle specimen, from Charles Holder's Marvels of Animal Life (1885)[55]

Artist's impression of the Thimble Tickle specimen, from Charles Holder's Marvels of Animal Life (1885)[55].jpg.webp) The "life-sized" concrete and metal sculpture of the Thimble Tickle giant squid, Glovers Harbour (July 2017)

The "life-sized" concrete and metal sculpture of the Thimble Tickle giant squid, Glovers Harbour (July 2017).jpg.webp) Sculpture with accompanying information plaque detailing the specimen's history

Sculpture with accompanying information plaque detailing the specimen's history

See also

- Centro del Calamar Gigante – giant squid museum in Luarca, Spain

- List of designated places in Newfoundland and Labrador

Notes

- Lovell's Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871 lists[19] two people by this name residing in Harbour Grace—a carpenter and a labourer.[5]

- The remainder resettled to Leading Tickles, Point Leamington, and Deer Lake.[33]

- Foulds was chosen because of his prior experience building large-scale community monuments in Saskatchewan, including "a giant turtle, a moose and a woolly mammoth".[10][53]

References

- Coast of Bays—Central—Notre Dame. Elections Canada.

- House of Assembly Act, RSNL 1990, c H-10. Queen's Printer, St. John's.

- Elections Newfoundland & Labrador (2020). 2019 Provincial General Election Report. St. John's. 330 pp.

- Statistics Canada (2007). Standard Geographical Classification (SGC), 2006. Volume I. The Classification. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 12-571-XIE. Ottawa. 635 pp. ISBN 0-662-43691-1.

- Smallwood, J.R., R.D.W. Pitt, C. Horan & B.G. Riggs (eds.) (1984). Glovers Harbour. [pp. 539–540] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 2: Fac–Hoy. Newfoundland Book Publishers, St. John's. xiii + 1104 pp. ISBN 978-0-920508-16-9.

- Statistics Canada (2017). Census Profile, 2016 Census: Glovers Harbour, Designated place, Newfoundland and Labrador and Newfoundland and Labrador. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released 29 November 2017.

- Newfoundland and Labrador Directory of Local Service Districts. Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism, St. John's. 5 pp.

- Glovers Harbour. Natural Resources Canada.

- Consolidated Newfoundland Regulation 1028/96. Queen's Printer, St. John's.

- Harvey, K. (reporter) (2004). Sizable squid in Glovers Harbour, N.L.. [video] CBC Here & Now, 23 January 2004.

- Dave Marsh interview, March 29, 1988. [audio recording] Digital Archives Initiative, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Canadian Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (1968). Gazetteer of Canada: Newfoundland and Labrador. Energy, Mines and Resources Canada, Ottawa. xiii + 252 pp. OCLC 395303369

- Socio-economic overview of Leading Tickles Area of Interest (AOI), Newfoundland: executive summary. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, May 2004. 16 pp.

- Glovers Point. Natural Resources Canada.

- MacLachlan, K., B.H. O'Brien & G.R Dunning (2001). Redefinition of the Wild Bight Group, Newfoundland: implications for models of island-arc evolution in the Exploits Subzone. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38(6): 889–907. doi:10.1139/e01-006

- Lockport Mine – Copper–Zinc. The Matty Mitchell Prospectors Resource Room, October 2010.

- Marsh, B. (2016). Resettlement in our backyard. Anglo Newfoundland Development Company, 25 July 2016.

- The Giant Squid of Thimble Tickle. [information plaque] Giant Squid Interpretation Site, Glovers Harbour.

- Lovell, J. (1871). Harbor Grace. [pp. 259–262] In: Lovell's Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871. John Lovell, Montreal. 380 pp. OCLC 1019499731

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1903). Glover Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/158503 176], 178, 180] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1901. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denominations, professions, &c. J.W. Withers, St. Jonh's. xxx + 457 pp. OCLC 456605290

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1914). Glover's Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/56668 206], 208, 210] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1911. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denomination, profession, &c. J.W. Withers, St. Jonh's. xxxi + 505 pp. OCLC 21658161

- Colonial Secretary's Office (1923). Glover's Harbor. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/49155 206], 208, 210] In: Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1921. Table I. Population, sex, condition, denomination, profession, etc. St. John's. xxiii + 512 pp. OCLC 797071136

- Newfoundland 1921 Census: Glovers Harbour, Twillingate District. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Department of Public Health and Welfare (1937). Glover's Harbour. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/51209 42], 190, 452, 608, 868] In: Tenth Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1935. Volume I. Population by districts and settlements. The Evening Telegram, St. John's. 961 + xxix pp. OCLC 8351268

- Newfoundland's 1935 Provincial Census, District of Twillingate: Community of Glovers Harbour. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1949). Glover's Harbour. [pp. [https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns_tools/id/121911 3], 25, 54, 71, 94, 245] In: Eleventh Census of Newfoundland and Labrador 1945. Volume I. Population. Ottawa. xvi + 252 pp. OCLC 21641833

- Newfoundland's 1945 Provincial Census, Green Bay District: Community of Glover's Harbour. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Population of Communities by Consolidated Census Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 1991 and 1996 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Population of Communities by Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 2001 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Population of Communities by Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS): Newfoundland and Labrador, 2006 Census. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- 2011 Census Population, Census Consolidated Subdivisions (CCS) by Community: Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- 2016 Census Population, by 2011 Census Consolidated Subdivision (CCS) by Community: Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency.

- Smallwood, J.R., C.F. Poole & R.H. Cuff (eds.) (1991). Lockesporte. [p. 355] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 3: Hub–M. Harry Cuff Publications, St. John's. xvii + 687 pp. ISBN 978-0-9693422-2-9.

- Poole, C.F. & R.H. Cuff (eds.) (1994). Winter House Cove, Seal Bay. [p. 590] In: Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador. Volume 5: S–Z. Harry Cuff Publications, St. John's. xv + 706 pp. ISBN 978-0-9693422-5-0.

- Power, A.S. & D. Mercer (2002). The role of fishers knowledge in implementing ocean act initiatives in Newfoundland and Labrador. [pp. 20–24] In: N. Haggan, C. Brignall & L. Wood (eds.) Putting fishers' knowledge to work: conference proceedings August 27–30, 2001. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 11(1): 1–504.

- Verrill, A.E. (1880). The cephalopods of the north-eastern coast of America. Part I.—The gigantic squids (Architeuthis) and their allies; with observations on similar large species from foreign localities. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 5(1)[Dec. 1879 – Mar. 1880]: 177–257. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.35965

- Verrill, A.E. (1880). Synopsis of the Cephalopoda of the north-eastern coast of America. The American Journal of Science (ser. 3)19(112)[Apr.]: 284–295.

- Ellis, R. (1998). The Search for the Giant Squid. Lyons Press, New York. ix + 322 pp. ISBN 1-55821-689-8.

- Sweeney, M.J. & C.F.E. Roper (2001). Records of Architeuthis Specimens from Published Reports. [Last updated 4 May 2001.] National Museum of Natural History. 132 pp. [unpaginated] [Archived from the original on 2 October 2011.]

- A Collection of Newfoundland Wills (M): Abraham Martin. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

- Wood, G.L. (1982). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Third edition. Guinness Superlatives, London. 252 pp. ISBN 0-85112-235-3.

- Carwardine, M. (1995). The Guinness Book of Animal Records. Guinness Publishing, Enfield. 256 pp. ISBN 0-85112-658-8.

- Glenday, C. (ed.) (2014). Mostly molluscs. [pp. 62–63] In: Guinness World Records 2015. Guinness World Records. 255 pp. ISBN 1-908843-70-5.

- O'Shea, S. & K. Bolstad (2008). Giant squid and colossal squid fact sheet. The Octopus News Magazine Online, 6 April 2008.

- Roper, C.F.E. & E.K. Shea (2013). Unanswered questions about the giant squid Architeuthis (Architeuthidae) illustrate our incomplete knowledge of coleoid cephalopods. American Malacological Bulletin 31(1): 109–122. doi:10.4003/006.031.0104

- Yukhov, V.L. (2014). Гигантские кальмары рода Architeuthis в Южном океане / Giant calmaries Аrchiteuthis in the Southern ocean. [Gigantskiye kalmary roda Architeuthis v Yuzhnom okeane.] Ukrainian Antarctic Journal no. 13: 242–253. (in Russian)

- McClain, C.R., M.A. Balk, M.C. Benfield, T.A. Branch, C. Chen, J. Cosgrove, A.D.M. Dove, L.C. Gaskins, R.R. Helm, F.G. Hochberg, F.B. Lee, A. Marshall, S.E. McMurray, C. Schanche, S.N. Stone & A.D. Thaler (2015). Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3: e715. doi:10.7717/peerj.715

- Dery, M. (2013). The Kraken wakes: what Architeuthis is trying to tell us. Boing Boing, 28 January 2013.

- Ganeri, A. (1990). The Usborne Book of Ocean Facts. Usborne Publishing, London. 48 pp. ISBN 978-0-7460-0621-4.

- Hickey, S. (2009). Super squid: Museum set to open next month. Advertiser (Grand Falls), 25 May 2009.

- 2018 Traveller's Guide: Lost and Found. Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism, St. John's. 460 pp.

- The Giant Squid - Glover's Harbour. Postage Stamp Guide.

- Life-Size Statue of Monster Squid. RoadsideAmerica.com.

- Hickey, S. (2010). Canada Post celebrates the giant squid. Advertiser (Grand Falls), 17 June 2010.

- Holder, C.F. (1885). Marvels of Animal Life. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. x + 240 pp. OCLC 29790638

Further reading

- Anon. (2000). Salute to Newfoundland communities: Glovers Harbour. The Newfoundland Herald vol. 55, no. 8.

- Carberry, N. (2001). Giant squid makes second landing in Glovers Harbour. Advertiser (Grand Falls) vol. 65, no. 63.

- Glover's Harbour: New Cemetery. Newfoundland's Grand Banks.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glovers Harbour, Newfoundland and Labrador. |

- History of Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- Drone footage of Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- "Doorstep of Heaven" – musical tribute to Glovers Harbour on YouTube

- Giant Squid Interpretation Site – Adventure Central Newfoundland