Gondophares

Gondophares I was the founder of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom and its most prominent king, ruling from 19 to 46. A member of the House of Suren, he belonged to a line of local princes who had governed the Parthian province of Drangiana since its disruption by the Indo-Scythians in c. 129 BC. During his reign, his kingdom became independent from Parthian authority and was transformed into an empire, which encompassed Drangiana, Arachosia, and Gandhara.[1] He is generally known from the dubious Acts of Thomas, the Takht-i-Bahi inscription, and coin-mints in silver and copper.

| Gondophares | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings | |

Silver coin of Gondophares, minted in Drangiana | |

| Indo-Parthian king | |

| Reign | c. 19 – c. 46 |

| Successor | Ortaghnes (Drangiana and Arachosia) Abdagases I (Gandhara) |

| Died | 46 |

| House | House of Suren |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

He was succeeded in Drangiana and Arachosia by Ortaghnes, and in Gandhara by his nephew Abdagases I.[2][3]

Etymology

The name of Gondophares was not a personal name, but an epithet that is the Middle Iranian version of the Old Iranian name 𐎻𐎡𐎭𐎳𐎼𐎴𐎠 (Vindafarnâ, "May he find glory" (cf. Greek Ἰνταφέρνης, Intaphernes)), which was also the name of one of the six nobles that helped the Achaemenid king of kings (shahanshah) Darius the Great (r. 522 BC – 486 BC) to seize the throne.[4][5] In old Armenian, it is "Gastaphar". “Gundaparnah” was apparently the Eastern Iranian form of the name.[6]

Ernst Herzfeld claims his name is perpetuated in the name of the Afghan city Kandahar, which he founded under the name Gundopharron.[7]

Background

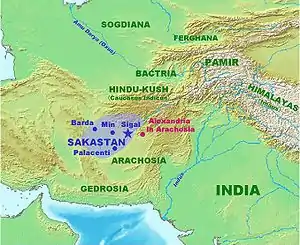

Gondophares was a member of the House of Suren, one of the most esteemed families in Arsacid Iran, that not only had the hereditary right to lead the royal military, but also to place the crown on the Parthian king at the coronation.[4] In c. 129 BC, the eastern portions of the Parthian Empire, primarily Drangiana, was invaded by nomadic peoples, mainly by the Eastern Iranian Saka (Indo-Scythians) and the Indo-European Yuezhi, thus giving the rise to the name of the province of Sakastan ("land of the Saka").[8][9]

As a result of these invasions, the Suren family was given control of Sakastan in order to defend the empire from further nomad incursions; the Surenids not only managed to repel the Indo-Scythians, but also eventually invade and seize their lands in Arachosia and Punjab, thus resulting in the establishment of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom.[4]

Rule

Gondophares ascended the throne in c. 19, and quickly declared independence from the Parthian Empire, minting coins in Drangiana where he assumed the Greek title of autokrator ("one who rules by himself").[10]

Gondophares I has traditionally been given a later date; the reign of one king calling himself Gondophares has been established at 20 AD by the rock inscription he set up at Takht-i-Bahi near Mardan, Pakistan, in 46 AD.,[11] and he has also been connected with the third-century Acts of Thomas.

Gondophares I took over the Kabul valley and the Punjab and Sindh region area from the Scythian king Azes. In reality, a number of vassal rulers seem to have switched allegiance from the Indo-Scythians to Gondophares I. His empire was vast, but was only a loose framework, which fragmented soon after his death. His capital was the Gandharan city of Taxila.[12] Taxila is located in Punjab to the west of the present Islamabad.

Chronology

On the coins of Gondophares, the royal names are Iranian, but the other legends of the coins are in Greek and Kharoṣṭhī.

Ernst Herzfeld maintained that the dynasty of Gondophares represented the House of Suren.[13]

The Biblical Magus "Gaspar"

The name of Gondophares was translated in Armenian in "Gastaphar", and then in Western languages into "Gaspar[d]". He may be the "Gaspar[d], King of Persia", who, according to apocryphal texts and eastern Christian tradition, was one of the three Biblical Magi who attended the birth of Christ.[14] Through this interaction and association, Gaspar[d] was adopted by the Europeans (and in Western tradition) as a male first name.

Connection with Saint Thomas and Apollonius of Tyana

The apocryphical Acts of Thomas mentions one king Gudnaphar. This king has been associated with Gondophares I by scholars such as M. Reinaud, as it was not yet established that there were several kings with the same name. Since St. Thomas is said to have lived there in a specific time frame, this is often used to provide more specific chronology to an otherwise historiographically lacking time frame.[15] Richard N. Frye, Emeritus Professor of Iranian Studies at Harvard University, has noted that this ruler has been identified with a king called Caspar in the Christian tradition of the Apostle St Thomas and his visit to India.[16] Recent research by R.C. Senior shows with some certainty that the king who best fits these references was Gondophares-Sases, the fourth king using the title Gondophares.[17]

A. D. H. Bivar, writing in The Cambridge History of Iran, said that the reign dates of one Gondophares recorded in the Takht-i Bahi inscription (20–46 or later AD) are consistent with the dates given in the Apocryphal Acts of Thomas for the Apostle's voyage to India following the Crucifixion in c. 30 AD.[18][19] B. N. Puri, of the Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, University of Lucknow, India, also identified Gondophares with the ruler said to have been converted by Saint Thomas the Apostle.[20] The same goes for the reference to an Indo-Parthian king in the accounts of the life of Apollonius of Tyana. Puri says that the dates given by Philostratus in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana for Apollonius' visit to Taxila, 43–44 AD, are within the period of the reign of Gondophares I, who also went by the Parthian name, Phraotes.[21] Saint Thomas was brought before King Gundaphar (Gondophares) at his capital, Taxila.[22] "Taxila" is the Greek form of the contemporary Pali name for the city, “Takkasila”, from the Sanskrit “Taksha-sila”. The name of the city was transformed in subsequent legends concerning Thomas, which were consolidated into the Historia Trium Regum (History of the Three Kings) by John of Hildesheim (1364–1375), into "Silla", "Egrisilla", "Grisculla", and so on,[23] the name having undergone a process of metamorphosis similar to that which transformed “Vindapharnah” (Gondophares) to “Caspar”. Hildesheim's Historia Trium Regum says: “In the third India is the kingdom of Tharsis, which at that time was ruled over by King Caspar, who offered incense to our Lord. The famous island Eyrisoulla [or Egrocilla] lies in this land: it is there that the holy apostle St Thomas is buried”.[24] "Egrisilla" appears on the globe made in Nuremberg by Martin Behaim in 1492, where it appears on the southernmost part of the peninsula of Hoch India, “High India” or “India Superior”, on the eastern side of the Sinus Magnus ("Great Gulf", the Gulf of Thailand): there Egrisilla is identified with the inscription, das lant wird genant egtisilla, (“the land called Egrisilla”). In his study of Behaim's globe, E. G. Ravenstein noted: “Egtisilla, or Eyrisculla [or Egrisilla: the letters “r” and “t” in the script on the globe look similar], is referred to in John of Hildesheim's version of the ‘Three Kings’ as an island where St. Thomas lies buried".[25]

References

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 35.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 37.

- Gazerani 2015, p. 25.

- Bivar 2002, pp. 135-136.

- Gazerani 2015, p. 23.

- Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, A History of Zoroastrianism, Leiden, Brill, 1991, pp.447–456, n.431.

- Ernst Herzfeld, Archaeological History of Iran, London, Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1935, p.63.

- Frye 1984, p. 193.

- Bosworth 1997, pp. 681-685.

- Gazerani 2015, pp. 24-25.

- A. D. H. Bivar, "The History of Eastern Iran", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol.3 (1), The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods, London, Cambridge University Press, 1983, p.197.

- B. N. Puri, “The Sakas and Indo-Parthians”, in A.H. Dani, V. M. Masson, Janos Harmatta, C. E. Boaworth, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 2003, Chapter 8, p.196

- Ernst Herzfeld, Archaeological History of Iran, London, Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1935, p.63; name="Bivar_2003"/> cf. name="Bivar_1983_51">Bivar, A. D. H. (1983), "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, 3, London: Cambridge UP, p. 51

- Alfred von Gutschmid, Die Königsnamen in den apokryphen Apostelgeschichten, in the Rheinisches Museum für Philologie (1864), XIX, 161-183, nb p.162; Mario Bussagli, "L'art du Gandhara", p.207

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 9780802137975.

- Richard N. Frye, “The Fall of the Graeco-Bactrians: Sakas and Indo-Parthians”, in Sigfried J. de Laet, History of Humanity, London, New York and Paris, Routledge and Unesco, Volume III, 1996, Joachim Herrmann and Erik Zürcher (eds.), From the Seventh Century BC to the Seventh Century AD, p.455.

- Robert C. Senior, Indo-Scythian Coins and History, Volume 4: Supplement, London, Chameleon Press, (2006).

- W. Wright (transl.), The Apocryphal Acts of Thomas, Leiden, Brill, 1962, p.146; cited in A. D. H. Bivar, "The History of Eastern Iran", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol.3 (1), The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods, London, Cambridge University Press, 1983, p.197.

- India and the Apostle Thomas, A. E. Medlycott, fully reproduced with illustrations (including the coins of Gondaphares) in the Indian Church History Classics ed. George Menachery, Ollur, 1998

- B. N. Puri, “The Sakas and Indo-Parthians”, in János Harmatta, B. N. Puri and G.F. Etemadi (editors), History of civilizations of Central Asia, Paris, UNESCO, Vol.II, 1994, p.196.

- Puri, “The Sakas and Indo-Parthians”, p.197.

- A. E. Medlycott, India and the Apostle Thomas, London, David Nutt, 1905, Chapter 1, “The Apostle Thomas and Gondophares the Indian King”

- Frank Schaer, The Three Kings of Cologne, Heidelberg, Winter, 2000, Middle English Texts no.31, p.196.

- Joannes of Hildesheim, The Three Kings of Cologne: An Early English Translation of the "Historia Trium Regum" together with the Latin Text, London, Trubner, 1886; repr. Elibron Classics, 2001, cap.xi, pp.227–28; translation by F.H. Mountney, The Three Kings of Cologne, Gracewing Publishing, 2003, pp.31, 47.

- E. G. Ravenstein, Martin Behaim: His Life and His Globe, London, George Philip, 1908, p.95.

Sources

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1997). "Sīstān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 681–685. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Schmitt, R. (1995). "DRANGIANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–537.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

The history of ancient iran.

- Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran's National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (2002). "GONDOPHARES". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, Fasc. 2. pp. 135–136.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gondophares. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). 1911.

- A. E. Medlycott, India and the Apostle Thomas, London 1905: Chapter i: "The Apostle Thomas and Gondophares the Indian king"

- Coins of Gondophares

- Indo-Parthian coinage