Gospels of Otto III

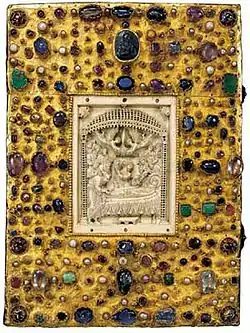

The Gospels of Otto III (Munich, Bayer. Staatsbib., Clm. 4453)[1] is considered a superb example of Ottonian art because of the scope, planning, and execution of the work.[2] The book has 276 parchment pages (334 by 242 mm, 13.1 by 9.5 inches) and has twelve canon tables, a double page portrait of Otto III, portraits of the four evangelists, and 29 full page miniatures illustrating scenes from the New Testament.[3] The cover is the original, with a tenth-century carved Byzantine ivory inlay representing the Dormition of the Virgin. Produced at the monastery at Reichenau Abbey in about 1000 CE., the manuscript is an example of the highest quality work that was produced over 150 years at the monastery.[2][4]

| Gospel Book of Otto III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Manuscript |

| Date | 998 to 1001 |

| Patron | Otto III |

Description

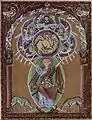

The cover of the book is a tribute to its contents; it is jeweled with a centerpiece consisting of a Byzantine ivory inlay of the Dormition of the Virgin. The inlay was placed on the cover rather than inside the manuscript because the text of the four gospels does not include reference to the Virgin Mary's death.[4] The book's cover was considered so beautiful that the book was commonly taken unopened to church services as a symbol of Christ, even if the text was not used in the service.[4] The book was extremely valuable and represents the height of Ottonian culture.[5] One of the most important elements of the book is its portrait of the emperor which highlights its dedication to him. The portrait uses hierarchic scaling to identify him as the main subject by making him larger than the others and having him sitting in a temple. The Otto III portrait does not include a reference to God. The majesty of the scene is enough to imply the emperor's divinity.[4]

The portrait of Otto also shows two military men on one side of him and two clergy on the other. The facing leaf shows four women appearing to approach him. They represented the four provinces of his empire (Germany, France, northern Italy, and the Slavic east) and are reminiscent of Christ being approached by the Magi.[6] The location of the portrait of Otto in the book between the canon tables and the portrait of St. Mathew, the first evangelist, is where a portrait of Christ is found in other gospel books. The perfection in this portrait of Otto is in the details, the colors and the representation of the figures.[4]

The extensive illuminations throughout the book are flat with no three-dimensional proportions and done with fine detail and brilliant colors. They are generally placed near the text to illustrate the scenes from the New Testament.[2]

The decorations on the canon tables are influenced by manuscripts from the Carolingian era. Both Otto III and his Carolingian predecessor, Charlemagne, were fascinated with the ancient Romans. The book reflects that fascination. For example, the frieze has gables that are similar to the "roof plants" in gospels written at the Charlemagne Court Schools. This copying in his Gospels shows Otto's interest in incorporating work from Charlemagne's time and from ancient times. [4]

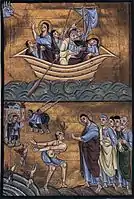

One of the plates in the book, XIX, shows Christ entering Jerusalem before his crucifixion. He is alone except for a man observing him from a tree, some figures looking on from below, and two boys attempting to cross the border between the lower into the upper area of the picture to place their clothing under the hooves of the donkey carrying Christ. The symbolism in the page and the artistic production make this work one of the best of Ottonian art.[4]

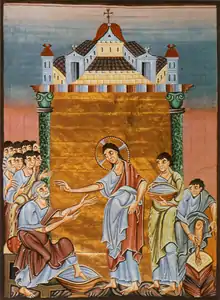

The illumination Footwashing of St. Peter, shows iconography that is included in many prior works, but transformed in this book. The stares of the other disciples, the glance and gesture of Christ, and the use of the ceremonial canopy with gold introduces high drama. It reflects back to art showing Moses removing his shoes at the burning bush and art in an early tenth-century Byzantine bible.[4]

Ottonian Art

The reign of Otto III, his ancestors, and some of his successors is known as the Ottonian period and art produced then is termed Ottonian art. The Ottonian period started in 955 and continued until the late 11th century.[7] The Ottonian emperors were Saxons and they controlled areas of Germany, Switzerland, part of Serbia, and northern Italy (modern day designations). They were allies of the pope and built a palace in Rome to be near him. They used their connection to the pope to bolster their claim to a God-given right to rule. The Ottonian emperors felt they were the equal to the greatest rulers.[8] Because of the strength of the Byzantines, the Ottos also sought to be close to them. Otto III's mother was a Byzantine princess. They also benefited from exposure to art from these other areas.[8]

Otto III was the third and last in a line of Ottos that were emperors. All were designated by the pope to be Holy Roman Emperors. Otto was only three when his father, Otto II, died and he became king. Otto III was designated Holy Roman Emperor by the pope when he was 16. His reign was not without controversy, For example, he and the pope responded to a rebellion by mutilating the leader's face and blinding him. The leader was one of Otto's former teachers.[4] He is recognized as one of few individuals to have had such a great impact by the age 21 when he died in 1022.[4][6] His advisors, who were talented and well known, did not always agree, but did achieve cohesion due to Otto's character.[4]

Following Otto III the emperor's title went to Henry II and then to several Saxon rulers. The Ottonian period ended with Henry IV.[4]

The art produced in the Ottonian period was intimately tied to the leaders, the Ottos. They were the patrons or donors for the works and were sometimes depicted in the books. While the Ottonian works were produced in abbeys and monasteries, they were based on the work done in the Court Schools of Charlemagne. The work evolved to include reflection of work done in the Late Antiquity and Byzantium.[2] Several great works were prepared during the Ottonian period in addition to the Gospel Book of Otto III, including the Book of Pericopes, the Ruodprecht Psalter, and the Quedlinburg Gospels.[2] The influence of the political and religious leaders resulted in the founding of several additional centers of excellence in book production, including Cologne school, the Echternach school, and Trier (one of the more importation schools in the late period).[2]

Of course, the quality of the work and the desire to emulate antiquity was not limited to manuscripts. Buildings were constructed with copies of the facades of Roman structures. Statues and tapestry emulated the ancients. Small gifts copying ancient models were produced as gifts for royalty and the wealthy.[9]

Importance

Otto III was influenced by Charlemagne's interest in ancient art. Otto's interest included ancient Roman sculpture, painting, architecture, metal work, and manuscripts.[7] Often medieval emperors modeled behavior and art on the classical history.[9] The works of the Ottonian period can be traced back to work done during Charlemagne’s reign. Evidence is found in the comparison of evangelist portraits in the Lorsch Gospels produced at one of the Court Schools of Charlemagne to the portraits in the Codex Gero produced by artists in the Reichenau monastery. The comparison shows that the artists at Reichenau used the work from the Charlemagne era as the model for their work.[4] The art produced at the Reichenau monastery was recognized as exemplary. Figures in Ottonian works and art produced by others were often presented with in a frontal view, which is used for Christ and rulers.[4]

The first letter of a page (in addition to the calligraphy, human figures, and illumination) was considered art, particularly with Ottonian art. Sometimes the first letter occupied an entire page, with intricate borders on the page and complex interlacing within the letter. Following the Carolingian precedent, the calligraphy was more important to the Ottonians than the pictures.[4]

Manuscripts during this period were developed at some of the major monasteries and in the bishops' schools. Historians are able to trace the development of techniques from the early 10th century at Reichenau to works done there in the late 11th century so that they can identify works from the Ottonian period.[4]

Since the book was written before the invention of the printing press, it was prepared manually. The scribes and artists would work for years on one book.[4] Extensive labor was required; often the same person that wrote the book prepared the materials. The hides of animals were dried and processed to make the parchment for the book. Inks were mixed. The parchment was lined to facilitate the lettering. An existing version was used by the scribe as the source. Artists added elaborate and detailed illustrations. Finally, a cover was added to the book. For the most lavish books, the cover would have jewels and ivory engravings.[10] The book with its ivory carving and jewels is a fine example of these techniques.[2]

The lack of social status held by the artists and scribes that produced the illuminated books is evident from the lack of attribution in the books. A few scribes, such as Liuthar, were recognized. The book was thought to have been produced by the Liuthard Group in the abbey due to its superb quality and style.[3]

The Benedictine abbey at Reichenau produced high quality manuscripts between 970 and 1010 or 1020 for the wealthy, kings, bishops and emperors.[4] They are highly valued works because of the quality of the illuminations and miniatures and the precision of the text. The monks at the Reichenau scriptorium produced manuscripts of such artistic and historic value and innovation that ten of them, including the book, were listed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2003.[11] The number of well-regarded manuscripts from the Reichenau monks is testimony not only to their artistic talents, but also their strength and dedication (the work was slow, exacting, and took a lot of time, so producing so many documents of such excellence is a tribute to them).[1]

The importance of the book is indicated by its decorations, one of the important high points in Ottonian book illumination, and the placement of the miniatures in chronological order.[7]

The manuscript was given by Otto III to Henry II who donated it to the Cathedral of Bamberg where it remained until 1803. It was removed to the Bavarian State Library in Munich to protect the valuable materials in its binding and cover.[4]

See also

Gallery

Master of the Gospel. The Gospel Book of Otto III

Master of the Gospel. The Gospel Book of Otto III St. Luke. Gospel Book of Otto III

St. Luke. Gospel Book of Otto III

Gospel Book of Otto III

Gospel Book of Otto III

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gospels of Otto III. |

- "Book Illuminations from the Reichenau Monastery". Bayerische StaatsBibliothek Munchener digitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliothek. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- Hourihane, Colum P. (2013). "The Gospels of Otto III". The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Section IV Part 2.

- Mütherich, Florentine (2003). "Gospels of Otto III". Grove Art Online. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1999). Ottonian Book Illumination, an Historical Study. CSU San Jose: Harvey Miller Publishers. pp. 11, 26, 31, 44, 71–73, 125, 157–158, 162–163. ISBN 1872501745.

- Beattie, Blake (2002). "A Short History of the Middle Ages by Barbara H. Rosenwein". Arthuriana. 12 (3): 157–159. doi:10.1353/art.2002.0065. ISSN 1934-1539. S2CID 161323730.

- Petzold, Andreas (August 8, 2013). "Gospel Book of Otto III". SmartHistory. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- Kuder, Ulrich (2015). "Ottonian Art". Oxford Art Online, Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T064248. ISBN 9781884446054.

- Sorabella, Jean (2008). ""Ottonian Art." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Remiet, Pierre (October 2001). "Classical Antiquity in the Middle Ages in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "The Art of the Book in the Middle Age". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. October 2001. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "UNESCO Memories of the World". UNESCO Memories of the World. Retrieved April 6, 2020.