Great-circle navigation

Great-circle navigation or orthodromic navigation (related to orthodromic course; from the Greek ορθóς, right angle, and δρóμος, path) is the practice of navigating a vessel (a ship or aircraft) along a great circle. Such routes yield the shortest distance between two points on the globe.[1]

Course

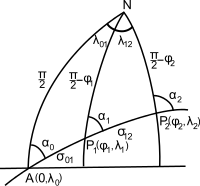

The great circle path may be found using spherical trigonometry; this is the spherical version of the inverse geodesic problem. If a navigator begins at P1 = (φ1,λ1) and plans to travel the great circle to a point at point P2 = (φ2,λ2) (see Fig. 1, φ is the latitude, positive northward, and λ is the longitude, positive eastward), the initial and final courses α1 and α2 are given by formulas for solving a spherical triangle

where λ12 = λ2 − λ1[note 1] and the quadrants of α1,α2 are determined by the signs of the numerator and denominator in the tangent formulas (e.g., using the atan2 function). The central angle between the two points, σ12, is given by

(The numerator of this formula contains the quantities that were used to determine tanα1.) The distance along the great circle will then be s12 = Rσ12, where R is the assumed radius of the earth and σ12 is expressed in radians. Using the mean earth radius, R = R1 ≈ 6,371 km (3,959 mi) yields results for the distance s12 which are within 1% of the geodesic distance for the WGS84 ellipsoid.

Finding way-points

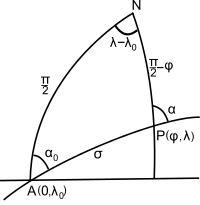

To find the way-points, that is the positions of selected points on the great circle between P1 and P2, we first extrapolate the great circle back to its node A, the point at which the great circle crosses the equator in the northward direction: let the longitude of this point be λ0 — see Fig 1. The azimuth at this point, α0, is given by

Let the angular distances along the great circle from A to P1 and P2 be σ01 and σ02 respectively. Then using Napier's rules we have

- (If φ1 = 0 and α1 = 1⁄2π, use σ01 = 0).

This gives σ01, whence σ02 = σ01 + σ12.

The longitude at the node is found from

Finally, calculate the position and azimuth at an arbitrary point, P (see Fig. 2), by the spherical version of the direct geodesic problem.[note 5] Napier's rules give

The atan2 function should be used to determine σ01, λ, and α. For example, to find the midpoint of the path, substitute σ = 1⁄2(σ01 + σ02); alternatively to find the point a distance d from the starting point, take σ = σ01 + d/R. Likewise, the vertex, the point on the great circle with greatest latitude, is found by substituting σ = +1⁄2π. It may be convenient to parameterize the route in terms of the longitude using

Latitudes at regular intervals of longitude can be found and the resulting positions transferred to the Mercator chart allowing the great circle to be approximated by a series of rhumb lines. The path determined in this way gives the great ellipse joining the end points, provided the coordinates are interpreted as geographic coordinates on the ellipsoid.

These formulas apply to a spherical model of the earth. They are also used in solving for the great circle on the auxiliary sphere which is a device for finding the shortest path, or geodesic, on an ellipsoid of revolution; see the article on geodesics on an ellipsoid.

Example

Compute the great circle route from Valparaíso, φ1 = −33°, λ1 = −71.6°, to Shanghai, φ2 = 31.4°, λ2 = 121.8°.

The formulas for course and distance give λ12 = −166.6°,[note 8] α1 = −94.41°, α2 = −78.42°, and σ12 = 168.56°. Taking the earth radius to be R = 6371 km, the distance is s12 = 18743 km.

To compute points along the route, first find α0 = −56.74°, σ1 = −96.76°, σ2 = 71.8°, λ01 = 98.07°, and λ0 = −169.67°. Then to compute the midpoint of the route (for example), take σ = 1⁄2(σ1 + σ2) = −12.48°, and solve for φ = −6.81°, λ = −159.18°, and α = −57.36°.

If the geodesic is computed accurately on the WGS84 ellipsoid,[4] the results are α1 = −94.82°, α2 = −78.29°, and s12 = 18752 km. The midpoint of the geodesic is φ = −7.07°, λ = −159.31°, α = −57.45°.

Gnomonic chart

A straight line drawn on a gnomonic chart would be a great circle track. When this is transferred to a Mercator chart, it becomes a curve. The positions are transferred at a convenient interval of longitude and this is plotted on the Mercator chart.

See also

Notes

- In the article on great-circle distances, the notation Δλ = λ12 and Δσ = σ12 is used. The notation in this article is needed to deal with differences between other points, e.g., λ01.

- A simpler formula is

- These equations for α1,α2,σ12 are suitable for implementation

on modern calculators and computers. For hand computations with logarithms,

Delambre's analogies[2] were usually used:

- A simpler formula is

- The direct geodesic problem, finding the position of P2 given P1, α1,

and s12, can also be solved by

formulas for solving a spherical triangle, as follows,

- A simpler formula is

- The following is used:

- λ12 is reduced to the range [−180°, 180°] by adding or subtracting 360° as necessary

References

- Adam Weintrit; Tomasz Neumann (7 June 2011). Methods and Algorithms in Navigation: Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation. CRC Press. pp. 139–. ISBN 978-0-415-69114-7.

- Todhunter, I. (1871). Spherical Trigonometry (3rd ed.). MacMillan. p. 26.

- McCaw, G. T. (1932). "Long lines on the Earth". Empire Survey Review. 1 (6): 259–263. doi:10.1179/sre.1932.1.6.259.

- Karney, C. F. F. (2013). "Algorithms for geodesics". J. Geodesy. 87 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1007/s00190-012-0578-z.

External links

- Great Circle – from MathWorld Great Circle description, figures, and equations. Mathworld, Wolfram Research, Inc. c1999

- Great Circle Mapper Interactive tool for plotting great circle routes.

- Great Circle Calculator deriving (initial) course and distance between two points.

- Great Circle Distance Graphical tool for drawing great circles over maps. Also shows distance and azimuth in a table.

- Google assistance program for orthodromic navigation