Great Phenol Plot

The Great Phenol Plot was a clandestine effort by the German Government during the early years of World War I to divert American-produced phenol away from the manufacture of high explosives that supported the British war effort. It was used by the German-owned Bayer company, who could no longer import phenol from Britain, to produce aspirin.

Background

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, most phenol used by American manufacturers was imported from the United Kingdom.[1] A major precursor compound in organic chemistry, phenol was used to make both the salicylic acid used to make aspirin, and the high explosive picric acid (trinitrophenol).[2] It was also a primary component for Thomas Edison's "Diamond Disc" phonograph records, which were made from glue-bound wood flour or ceramic coated in a layer of an early phenol-based plastic (unlike other disc records of the time, which were made from shellac).[3]

British phenol was soon being used almost exclusively for making explosives for the war effort, leaving little for export.[1] By 1915, the price of phenol rose to the point that Bayer's aspirin plant was forced to drastically cut production; this was especially problematic because Bayer was instituting a new branding strategy in anticipation of the expiry of the aspirin patent in the United States. Counterfeiters and Canadian importers and smugglers were stepping up to meet demand for aspirin, and the war had disrupted the links between the American Bayer plant (in Rensselaer, New York) and the central Bayer headquarters in Germany. Thomas Edison was also facing phenol supply problems; in response, he built a factory near Johnstown, Pennsylvania capable of manufacturing 12 short tons (11 t) of phenol per day. Edison's excess phenol seemed destined for American trinitrophenol production, which would be used to support the British.[3]

Plot

Although the United States remained officially neutral until April 1917, it was increasingly throwing its support to the Allies through trade, especially after the May 1915, sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania (whose death toll included 128 American passengers) by a German U-boat. While many Americans, including President Woodrow Wilson, supported the British, there was also considerable pro-German sentiment (though considerably less after the Lusitania's sinking). German ambassador Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff and Interior Ministry official Heinrich Albert were tasked with undermining American industry and maintaining public support for Germany. One of their agents was a former Bayer employee, Hugo Schweitzer.[4]

Schweitzer, with money funneled from Germany through Albert, set up a contract for a front company called the Chemical Exchange Association to buy all of Edison's excess phenol. Much of the phenol would go to the German-owned Chemische Fabrik von Heyden's American subsidiary; Heyden was the supplier of Bayer's salicylic acid for aspirin manufacture. By July 1915, Edison's plants were selling about three tons of phenol per day to Schweitzer; Heyden's salicylic acid production was soon back on line, and in turn Bayer's aspirin plant was running as well. Schweitzer sold the remainder of the phenol at a considerable profit, being careful to distribute it to only non-war-related industries.[5]

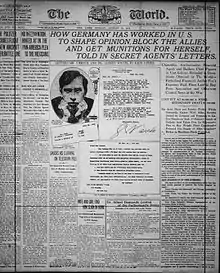

Albert, however, was under investigation by the Secret Service because of his propaganda activities. On July 24, 1915, he accidentally left his briefcase on a train; it was recovered by a Secret Service agent who had been following him.[6] The briefcase contained details about the phenol plot and other covert activities to indirectly aid the German war effort. Although it was not incriminating enough to bring charges against Albert or the other conspirators (since the United States was still officially neutral and trade with Germany was legal), the documents were soon leaked to the New York World, an anti-German newspaper.[7] The World published an exposé on August 15, 1915,[6] and the publicity soon forced Albert to stop funding the phenol purchases.[7]

Schweitzer quickly sought other financial backers. By September, he had signed a deal (backdated to June to hide Albert's involvement) with Richard Kny, a relative of the Heyden plant's manager. This allowed the phenol transfers to continue for a short while longer. By the time the plan was discontinued, it had succeeded in diverting enough phenol, according to Albert, to make about 4.5 million pounds (2,000 tonnes) of explosives. Schweitzer defended his actions, arguing that making medicine and disinfectants was a better use of the phenol than making weapons.[7] The public pressure soon forced Schweitzer and Edison to end the phenol deal, with the embarrassed Edison subsequently sending his excess phenol to the U.S. military, but by that time the deal had netted the plotters over $2 million (equivalent to $37.1 million in 2019) and there was already enough phenol to keep Bayer's aspirin plant running. Bayer's reputation took a large hit, however, just as the company was preparing to launch an advertising campaign to secure the connection between aspirin and the Bayer brand.[8]

References

- Schwarcz 2001, p. 60.

- Jeffreys 2008, pp. 109–110.

- Mann & Plummer (1991), pp. 39–40; Jeffreys (2008), pp. 109–113

- Mann & Plummer (1991), pp. 38–39

- Mann & Plummer (1991), pp. 40–41

- Jeffreys (2008), pp. 113

- Mann & Plummer (1991), pp. 41–42

- Jeffreys (2008), pp. 113–114

Notes

- Jeffreys, Diarmuid (2008). Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN 9781596918160.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mann, Charles C. & Plummer, Mark L. (1991). The Aspirin Wars: Money, Medicine, and 100 Years of Rampant Competition. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780394578941.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwarcz, Joe (2001). Radar, Hula Hoops, and Playful Pigs: 67 Digestible Commentaries on the Fascinating Chemistry of Everyday Life. Macmillan. ISBN 9780805074079.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)