Great desert skink

The great desert skink (Liopholis kintorei ), also known commonly as Kintore's egernia, is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to the western half of Australia.[3] It is a burrowing lizard and extremely social.

| Great desert skink | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Liopholis |

| Species: | L. kintorei |

| Binomial name | |

| Liopholis kintorei | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Etymology

The specific name, kintorei, is in honor of Algernon Keith-Falconer, 9th Earl of Kintore, a British politician who was a colonial governor of South Australia.[4]

Description

The great desert skink is a medium-sized skink, reaching an average snout-to-vent length (SVL) of 19 cm (about 7 in). It has smooth, small, glossy scales and is mostly rust-coloured on the top of the body, with the belly a vanilla color. It has relatively large circular eyes and a short snout.

Distribution and habitat

L. kintorei is native to the southwestern quarter of the Northern Territory, and dispersed slightly throughout most of Western Australia. As the common name suggests, it is a desert reptile, living in burrows. The burrows can extend up to 12 meters (40 ft) in length, and can have as many as 20 entrances.[5]

Behaviour

Researchers have recently made a stunning discovery with regard to L. kintorei — out of over 5,000 species of lizards documented, this species has been said to have "unique" behavior among them.[5] Individuals of the great desert skink appear to work in cooperation with one another to build and take care of their burrows, even digging out specific rooms for use as a defecatorium. Mates are faithful to one another and always mate with the same lizard, although 40 percent of males have been documented to mate with other females. The tunnels are mostly excavated by adults, while juvenile lizards contribute small "pop" holes to the system. DNA analysis has shown that immature lizards live in the same burrow with their siblings, regardless of age difference. The study, carried out in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, also revealed that all immature lizards were full siblings in 18 of 24 burrow systems. Researchers have confirmed that the lizards are family-based and keep the juveniles in the tunnel system until they mature.

References

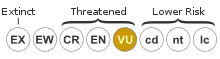

- Australasian Reptile & Amphibian Specialist Group (1996). "Liopholis kintorei ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T7040A12824494. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T7040A12824494.en.

- "Liopholis kintorei ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- Great desert skink at the Australian Reptile Online Database

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Egernia kintorei, p. 141).

- "Cooperative Lizard Living." Reptile Channel. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

Further reading

- Cogger HG (2014). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia, Seventh Edition. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. xxx + 1,033 pp. ISBN 978-0643100350.

- Stirling EC, Zietz A (1893). "Scientific Results of the Elder Exploring Expedition. Vertebrata. Mammalia. Reptilia". Trans. Royal Soc. South Australia 16: 154-176. (Egernia kintorei, new species, p. 171).

- Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry (2013). A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia, Fourth Edition. Sydney: New Holland Publishers. 522 pp. ISBN 978-1921517280.