Greater stick-nest rat

The greater stick-nest rat, also known as the house-building rat[3] and wopilkara[4] (Leporillus conditor) is a species of rodent in the family Muridae. They are about the size of a small rabbit and construct large nests of interwoven sticks. Once widespread across southern Australia, the population was reduced after European colonisation to one offshore island. The species has since been reintroduced to a series of protected and monitored areas, with varying levels of success.[5]

| Greater stick-nest rat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Muridae |

| Genus: | Leporillus |

| Species: | L. conditor |

| Binomial name | |

| Leporillus conditor (Sturt, 1848)[2] | |

.png.webp) | |

Taxonomy

A description of the species was given in a report of the explorer Charles Sturt, and published in 1848.[2][6] The species was placed as genus Mus, and later assigned to Leporillus, and so allied to the murid family of rodents. The type was collected in vegetation on the Darling River, around 45 miles from Laidley Ponds, the disposition of this specimen is unknown.[6]

Description

The species has a broad and short head, with wide and rounded ears. The length of the head and body combined in 190 to 260 millimetres, and a tail noticeably shorter than that, measuring from 148 to 180 mm. The weight ranges from 190 to 450 grams. The pelage is a uniform grey-brown colour at the upper-side, the buff to grey beneath is paler and the two colours blend where they meet. The visible parts of the foot are whitish at the inside and greyish brown at the outside, this is from 42 to 48 mm in length. The female possesses four teats, two pairs at the inguinal region.[7]

Behaviour

The behavioural description is of a passive and gentle species, largely active at night, with a herbivorous diet largely composed of succulent leaves. The 'nest' of L. conditor is sited at a cave, rocky outcrop or over a shrub, the construction reaching a metre in height and around two metres in width. The larger part of the nest is tightly woven from sticks, the inner part is built from softer grassy material.[7]

Mainland populations were reported to prefer building nests over slight depressions in the ground or above the burrows of other animals - which were used as escape routes - and some animals were known to weight their nests with small rocks.[8][9][10]

Nests were reported to be strong and secure enough to repel dingos and other predators.[10]

Breeding may occur throughout the year, although most often recorded during the austral spring, April to May, and they produce a litter of between one and four young.[7]

Distribution and habitat

It is now found naturally only in Australia on the Franklin Islands, with introduced or reintroduced populations on St Peter Island in the Nuyts Archipelago, Reevesby Island, Salutation Island, and a fenced off area at Roxby Downs in South Australia.[11]

Reintroduction attempts at Faure Island and Heirisson Prong in WA, Yookamurra Sanctuary and Venus Bay Conservation Park in SA, and Scotia Sanctuary in NSW all failed.[5] The longterm success of a series of translocations to the fenced Mount Gibson Sanctuary in WA is as yet undetermined,[5] while reintroduction attempts began in NSW's Mallee Cliffs National Park in September 2020.[12]

The species is scheduled to be reintroduced to Dirk Hartog Island following the complete removal of livestock and feral cats from the island.[13] It will also be translocated to a fenced landscape in NSW's Sturt National Park.[14]

It was formerly widespread in semi-arid habitat on the mainland,[15] where the soils were shallow with calcareous underlying strata.[16] Before the sharp decline in population in the late nineteenth century, the species was found south of a line from Shark Bay to the meeting of the rivers at the Murray–Darling basin and above the 28° southern latitude. The drastic contraction of the distribution range continued until the species could only be found at an island in the Nuyts Archipelago, from this population the species was reintroduced to the protected areas on the mainland and other islands.[7]

The drastic reduction in the range of this mammal is associated with the collapse of mammalian fauna in Australia (1875–1925), the causes of which are uncertain. The susceptibility of this species to a theorised epizootic event, an unidentified disease spreading from Western Australia, was estimated to be high in modelling of mammal's relative immunity.[17]

Its natural habitat is dry savanna, with perennial shrubland, especially of succulent and semi-succulent plant species including the chenopod and pig-face genera.[18]

The species is currently being bred in captivity at Monarto Safari Park and Adelaide Zoo, with progeny provided to reintroduction projects.[19]

References

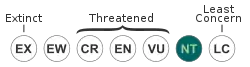

- Morris, K. & Copley, P. (2008). "Leporillus conditor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008. Listed as Vulnerable(VU D2 v3.1)

- Sturt, C. (1848). Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia (transcript). 1. London: T & W Boone. p. 120.

- "Stick-nest rat, house building rat (Leporillus conditor) / Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service". Trove. 18 October 2020.

- "Greater Stick-nest Rat - profile | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Short, Jeff; Copley, Peter; Ruykys, Laura; Morris, Keith; Read, John; Moseby, Katherine (8 October 2019). "Review of translocations of the greater stick-nest rat (Leporillus conditor): lessons learnt to facilitate ongoing recovery". Wildlife Research. 46 (6): 455–475. doi:10.1071/WR19021. ISSN 1448-5494.

- Musser, G.G.; Carleton, M.D. (2005). "Superfamily Muroidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 894–1531. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780195573954.

- "Our Curious Animals". Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 - 1954). 24 January 1935. p. 64. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "A RAT-HOUSE". World's News (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 1955). 19 July 1952. p. 30. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "JERBOA RAT". Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 - 1954). 3 March 1934. p. 21. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Stick-nest building mammal back in the Mallee". AWC - Australian Wildlife Conservancy. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- "Catch me if you can: WA's most wanted feline". PerthNow. 8 October 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Reintroducing locally extinct mammals to Sturt National Park | Centre for Ecosystem Science". www.ecosystem.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Ellis, M. (1995). A discussion of the large extinct rodents of Mootwingee National Park, western New South Wales. Australian Zoologist. 30:1-4.

- Josephine Flood (2004) Archaeology of the Dreamtime, J.B Publishing, Marleston p. 206 ISBN 1-876622-50-4

- Abbott, I. (December 2006). "Mammalian faunal collapse in Western Australia, 1875-1925: the hypothesised role of epizootic disease and a conceptual model of its origin, introduction, transmission, and spread". Australian Zoologist. 33 (4): 530–561. doi:10.7882/az.2006.024. ISSN 0067-2238.

- "The Action Plan for Australian Rodents". Department of the Environment. 1 April 1995. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Fluffy stick-nest rats born at Monarto Safari Park as part of conservation program". Monarto Safari Park. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.