Guatemala syphilis experiments

The syphilis experiments in Guatemala were United States-led human experiments conducted in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. The experiments were led by physician John Charles Cutler who also participated in the late stages of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Doctors infected soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases, without the informed consent of the subjects. The experiment resulted in at least 83 deaths.[1] Serology studies continued through 1953 involving the same vulnerable populations in addition to children from state-run schools, an orphanage, and rural towns, though the intentional infection of patients ended with the original study. On October 1, 2010, the U.S. President, Secretary of State and Secretary of Health and Human Services[2] formally apologized to Guatemala for the ethical violations that took place. Guatemala condemned the experiment as a crime against humanity, and a lawsuit has since been filed.[3]

Experiment

Historical context

Beginning in 1947, syphilis prevention research was being conducted on rabbits through injection of penicillin. Around this same time, there was a large push by medical professionals, including the U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Thomas Parran, to further the knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases and discover more viable treatment options in humans. With the onset of World War II, this emphasis for new knowledge became stronger and won more supporters. This was largely due to an effort to protect the U.S. military population from the increasing infections of STDs such as gonorrhea as well as the particularly painful regimen of prophylaxis that involved in the injection of a silver proteinate into subjects' penises.[4] At the time, it was estimated that venereal diseases would affect 350,000 soldiers, which would equate to eradicating 2 armed divisions for an entire year. The cost of these losses, which would sum up to about $34 million at the time, put an urgent strain on research for STD treatments.[4]

The first experiment following the push for new developments in STD treatment and preventative measures were the Terre Haute prison experiments from 1943–1944, which were conducted and supported by many of the same individuals who would go on to participate in the Guatemalan syphilis experiments only a few years later.[4][5] The goal of this experiment was to find a more suitable STD prophylaxis, by infecting human subjects recruited from prison populations with gonorrhea. Though at first, the idea of using human subjects was controversial, the support of Dr. Thomas Parran, and Executive Officer of the U.S. Army Medical Corps, Colonel John A. Rodgers allowed Dr. John F. Mahoney and Dr. Cassius J. Van Slyke to begin implementing the experiments. Dr. John Cutler, a young associate of Dr. Mahoney, helped conduct the experiments, and went on to lead the Guatemala syphilis experiments.

The experiments in Terre Haute were the precursor for the Guatemalan experiments. It was the first to demonstrate how earnestly military leaders pushed for new developments to combat STDs and their willingness to infect human subjects, and also explained why the study clinicians would choose Guatemala—to avoid the ethical constraints related to individual consent, other adverse legal consequences, and bad publicity.[4]

John Charles Cutler

The experiments were led by United States Public Health Service physician John Charles Cutler,[6] who had earlier participated in the similar Terre Haute prison experiments, in which volunteer prisoners were infected with gonorrhea.[4]

Cutler also later took part in the late stages of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. While the Tuskegee experiment followed the natural progression of syphilis in those already infected, in Guatemala, doctors deliberately infected healthy people with the diseases; some of which can be fatal if untreated. The goal of the study seems to have been to determine the effect of penicillin in the prevention and treatment of venereal diseases. The researchers paid prostitutes infected with syphilis to have sex with prisoners, while other subjects were infected by directly inoculating them with the bacterium.[7] Through intentional exposure to gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid, a total of 1,308 people were involved in the experiments. Of that group, with an age range of 10-72, 678 individuals (52%) can be said to have received a form of treatment.[4] Hidden from the public, John Charles Cutler utilized healthy individuals in order to improve what he called "pure science." [4]

Dr. John F. Mahoney

Dr. John F. Mahoney led the Terre Haute Prison experiments and supervised Dr. Cutler in the Guatemala Syphilis Experiment. Mahoney graduated from medical school in 1914 and by 1918 was titled Assistant Surgeon at the United States Public Health Service. By 1929, Dr. Mahoney worked as the director of the Venereal Disease Research Lab in Staten Island, where the Terre Haute experiments began in 1943, this is also where Cutler first assisted him. After stopping the Terre Haute experiments for lack of accurate infection of subjects with gonorrhea, Dr. Mahoney moved on to study the effects of penicillin on syphilis. His research found huge success for penicillin treatments and the US army embraced it in STD prescription. Although this seemed promising, Mahoney and his collaborators questioned the long term effectiveness of eliminating the disease altogether in individuals. Mahoney, Cutler, and other researchers, felt that a smaller, more controlled group of individuals to study would be more helpful in finding this cure. This led to the use of citizens in Guatemala as subjects.[4]

Genevieve Stout

Genevieve Stout was an employee of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau who promoted and established serological research in Guatemalan laboratories. She initiated the VDRL and Training Center within Central America starting in 1948 and she stayed in Guatemala until 1951. Here she conducted several independent serological experiments for STD research following Dr. Cutler.[4]

Dr. Funes and Dr. Salvado

Dr. Funes and Dr. Salvado were also employees of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau who remained in Guatemala after the work of Dr. Cutler. In order to advance in their careers, they opted to stay and continue observations on subjects of the Syphilis experiments, including data collections from orphans, inmates, psychiatric patients, and school kids. These periodic data collections consisted of blood specimens and lumbar punctures from participants. Data was shipped backed to the United States where many of these blood samples tested positive for syphilis. Dr. Funes collected samples from participants until 1953.[4]

Study details

The experiments were funded by a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the Pan American Sanitary Bureau and involved multiple Guatemalan government ministries.[7] A total of about 1,500 study subjects were involved, although the findings were never published.[7]

In archived documents, Dr. Thomas Parran, Jr., the U.S. Surgeon General at the time of the experiments, acknowledged that the Guatemalan work could not be done domestically, and details were hidden from Guatemalan officials.[8][9]

The study is officially stated to have ended in 1948. Eighty-three individuals died during the course of the experiment, though it is unclear as to whether or not the inoculations were the source of these deaths.[5]

Subjects

In total, 1,308 people were involved in this experiment, and of this group, 678 individuals were documented as getting some form of treatment. This population consisted of commercial sex workers, prisoners, soldiers, and mental hospital patients. Their ages ranged from 10 to 72, though the average subject was in their 20s. A documented subject profile provides a detailed description of what the subjects faced within this experiment:

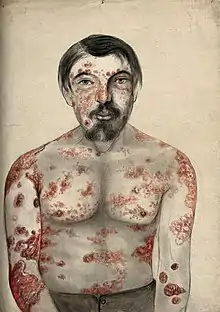

Berta was a female patient in the Psychiatric Hospital... in February 1948, Berta was injected in her left arm with syphilis. A month later, she developed scabies (an itchy skin infection caused by a mite). Several weeks later, Dr. Cutler noted that she also developed red bumps where he had injected her arm, lesions on her arms and legs, and her skin was beginning to waste away from her body. Berta was not treated for syphilis until three months after her injection. Soon after, on August 23, Dr. Cutler wrote that Berta appeared as if she was going to die, but he did not specify why. That same day he put gonorrheal pus from another male subject into both of Berta's eyes, as well as in her urethra and rectum. He also re-infected her with syphilis. Several days later, Berta's eyes were filled with pus from the gonorrhea, and she was bleeding from her urethra. Three days later, on August 27, Berta died.[4][10]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledges that "the design and conduct of the studies was unethical in many respects, including deliberate exposure of subjects to known serious health threats, lack of knowledge of and consent for experimental procedures by study subjects, and the use of highly vulnerable populations."[11] A total of 83 subjects died, though the exact relationship to the experiment remains undocumented.[4][11]

Aftermath

Apology and response

Professor Susan Mokotoff Reverby of Wellesley College uncovered information about these experiments. Reverby found the documents in 2005 while researching the Tuskegee syphilis study, in Cutler's archived papers, and shared her findings with United States government officials.[7][8]

Francis Collins, the NIH director at the time of the revelations, called the experiments "a dark chapter in history of medicine" and commented that modern rules prohibit conducting human subject research without informed consent.[12]

In October 2010, the U.S. government formally apologized and announced that the violation of human rights in that medical research was still to be condemned, regardless of how much time had passed.[13][14][15] Following the apology, Barack Obama requested an investigation to be conducted by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues on November 24, 2010. The commission concluded nine months later that the experiments "involved gross violations of ethics as judged against both the standards of today and the researchers' own understanding".[4] In a joint statement, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius said:

Although these events occurred more than 64 years ago, we are outraged that such reprehensible research could have occurred under the guise of public health. We deeply regret that it happened, and we apologize to all the individuals who were affected by such abhorrent research practices. The conduct exhibited during the study does not represent the values of the US, or our commitment to human dignity and great respect for the people of Guatemala.

President Barack Obama apologized to President Álvaro Colom, who had called the experiments "a crime against humanity".[16]

"It is clear from the language of the report that the U.S. researchers understood the profoundly unethical nature of the study. In fact the Guatemalan syphilis study was being carried out just as the “Doctors' Trial” was unfolding at Nuremberg (December 1946 – August 1947), when 23 German physicians stood trial for participating in Nazi programs to euthanize or medically experiment on concentration camp prisoners."[17]

The U.S. government asked the Institute of Medicine to conduct a review of these experiments beginning January 2011.[4][7]

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues Investigation

While the Institute of Medicine conducted their review, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues was asked to convene a panel of international experts to review the current state of medical research on humans around the world and ensure that these sorts of incidents do not occur again.[7] The Commission report, Ethically Impossible: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948, published in September 2011, aimed to answer four questions:

- What occurred in Guatemala between 1946 and 1948 involving a series of STD exposure studies funded by the U.S. PHS?

- To what extent were U.S. government officials and others in the medical research establishment at that time aware of the research protocols and to what extent did they actively facilitate or assist in them?

- What was the historical context in which these studies were done?

- How did the studies comport with or diverge from the relevant medical and ethical standards and conventions of the time? [4]

The investigation concluded that "the Guatemala experiments involved unconscionable basic violations of ethics, even as judged against the researchers' own recognition of the requirements of the medical ethics of the day."[4][18]

Human rights activists have called for subjects' families to be compensated.[6] As of 2017, the families still have not been compensated even though there have been several lawsuits.[19]

Manuel Gudiel Garcia v. Kathleen Sebelius

In March 2011, seven plaintiffs filed a federal class-action lawsuit against the U.S. government claiming damages for the Guatemala experiments.[3] This case argued that the United States was at fault due to not asking for consent. This lawsuit asked for money to compensate for medical damages and livelihood because most of the families were living in poverty. The case failed when a judge determined that the U.S. government could not be held liable for actions committed outside of the U.S.[19][20]

Estate of Arturo Giron Alvarez et al. v. The Johns Hopkins University et al.

In April 2015, 774 plaintiffs launched a lawsuit against Johns Hopkins University, the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Rockefeller Foundation seeking $1 billion for damages.[21] The hope was that compensation could be attained by targeting private institutions rather than the federal government.

In January 2019, U.S. District Judge Theodore Chuang rejected the defendants' argument that a recent Supreme Court decision shielding foreign corporations from lawsuits in U.S. courts over human rights abuses abroad also applied to domestic corporations absent Congressional authorization and decided to admit the trial.[22] The case is Estate of Arturo Giron Alvarez et al v. The Johns Hopkins University et al, U.S. District Court, District of Maryland, No. 15-00950.

See also

References

- "Guatemalans 'died' in 1940s US syphilis study". BBC News. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Maggie Fox, "U.S. apologizes for syphilis experiment in Guatemala", https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-guatemala-experiment/u-s-apologizes-for-syphilis-experiment-in-guatemala-idUSTRE6903RZ20101001

- Kakar, Aman (15 March 2011). "Guatemalans file class action suit over US medical experiments". JURIST. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015.

- Ethically Impossible: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948, Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, published 2011-09-13, accessed 2015-10-23

- Reverby, Susan M. (June 2012). "Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala". Public Health Reviews. 34 (1). doi:10.1007/bf03391665. ISSN 2107-6952.

- Chris McGreal (1 October 2010). "US says sorry for "outrageous and abhorrent" Guatemalan syphilis tests". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

Conducted between 1946 and 1948, the experiments were led by John Cutler, a US health service physician who would later be part of the notorious Tuskegee syphilis study in Alabama in the 1960s.

- "Fact Sheet on the 1946-1948 U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Inoculation Study". United States Department of Health and Human Services. nd. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- "Wellesley professor unearths a horror: Syphilis experiments in Guatemala". Boston Globe. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- "Exposed: US Doctors Secretly Infected Hundreds of Guatemalans with Syphilis in the 1940s". Democracy Now!. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "US medical tests in Guatemala 'crime against humanity'". BBC News. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- "Findings from a CDC Report on the 1946-1948 U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Inoculation Study", U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 30 September 2010

- Donald G. McNeil, Jr. (1 October 2010). "U.S. Apologizes for Syphilis Tests in Guatemala". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Hensley, Scott (1 October 2010). "U.S. Apologizes For Syphilis Experiments In Guatemala". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "U.S. apologizes for newly revealed syphilis experiments done in Guatemala". Washington Post. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

The United States issued an unusual apology Friday to Guatemala for conducting experiments in the 1940s in which doctors infected soldiers, prisoners and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

- "Time limitation under the United States Alien Tort Claims Act" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "US medical tests in Guatemala 'crime against humanity'". BBC News. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Nate, Jones. "Decades Later, NARA Posts Documents on Guatemalan Syphilis Experiments". NSA Archive. The George Washington University. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (September 14, 2011). "Lapses by American Leaders Seen in Syphilis Tests". New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015.

- Subramanian, Sushma (February 26, 2017). "Worse Than Tuskegee". SLATE. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Mariani, Mike (28 May 2015). "The Guatemala Experiments". Pacific Standard. The Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Laughland, Oliver (3 April 2015). "Guatemalans deliberately infected with STDs sue Johns Hopkins University for $1bn". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015.

- Johns Hopkins, Bristol-Myers must face $1 billion syphilis infections suit. (Reuters, Jan 2019, 5:23 PM)