Stanford prison experiment

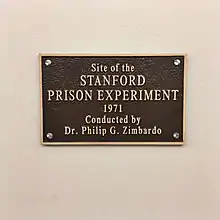

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a social psychology experiment that attempted to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power, focusing on the struggle between prisoners and prison officers. It was conducted at Stanford University on the days of August 15–21, 1971, by a research group led by psychology professor Philip Zimbardo using college students.[1] In the study, volunteers were assigned to be either "guards" or "prisoners" by the flip of a coin, in a mock prison, with Zimbardo himself serving as the superintendent. Several "prisoners" left mid-experiment, and the whole experiment was abandoned after six days. Early reports on experimental results claimed that students quickly embraced their assigned roles, with some guards enforcing authoritarian measures and ultimately subjecting some prisoners to psychological torture, while many prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse and, by the officers' request, actively harassed other prisoners who tried to stop it. The experiment has been described in many introductory social psychology textbooks,[2] although some have chosen to exclude it because its methodology is sometimes questioned.[3]

The U.S. Office of Naval Research[4] funded the experiment as an investigation into the causes of difficulties between guards and prisoners in the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps. Certain portions of it were filmed, and excerpts of footage are publicly available.

The experiment's findings have been called into question, and the experiment has been criticized for unscientific methodology.[5] Although Zimbardo interpreted the experiment as having shown that the "prison guards" instinctively embraced sadistic and authoritarian behaviors, Zimbardo actually instructed the "guards" to exert psychological control over the "prisoners". Critics also noted that some of the participants behaved in a way that would help the study, so that, as one "guard" later put it, "the researchers would have something to work with," which is known as demand characteristics. Variants of the experiment have been performed by other researchers, but none of these attempts have replicated the results of the SPE.[6]

Zimbardo's goals

The (archived) official website of the Stanford Prison Experiment describes the experiment goal as follows:

We wanted to see what the psychological effects were of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. To do this, we decided to set up a simulated prison and then carefully note the effects of this institution on the behavior of all those within its walls.[7]

A 1997 article from the Stanford News Service described experiment goals in a more detailed way:

Zimbardo's primary reason for conducting the experiment was to focus on the power of roles, rules, symbols, group identity and situational validation of behavior that generally would repulse ordinary individuals. "I had been conducting research for some years on deindividuation, vandalism and dehumanization that illustrated the ease with which ordinary people could be led to engage in anti-social acts by putting them in situations where they felt anonymous, or they could perceive of others in ways that made them less than human, as enemies or objects," Zimbardo told the Toronto symposium in the summer of 1996.[8]

Experimental method

Male participants were recruited and told they would participate in a two-week prison simulation. The team selected the 24 applicants whose test results predicted they would be the most psychologically stable and healthy.[9] These participants were predominantly white[10] and of the middle class.[7] The group was intentionally selected to exclude those with criminal backgrounds, psychological impairments, or medical problems. They all agreed to participate in a 7- to 14-day period and received $15 per day (roughly equivalent to $95 in 2019).[11]

The experiment was conducted in a 35-foot (10.5 m) sections of a basement of Jordan Hall (Stanford's psychology building). The prison had two fabricated walls, one at the entrance, and one at the cell wall to block observation. Each cell (6 × 9 feet, or 1.8 × 2.7 m), contained only a cot for the prisoners.[12] Prisoners were confined 24 hours/day. In contrast, the guards lived in a very different environment, separated from the prisoners. They were given rest and relaxation areas, and other comforts.

Twelve of the twenty-four participants were assigned the role of prisoner (nine plus three potential substitutes), while the other twelve were assigned the role of guard (also nine plus three potential substitutes). Zimbardo took on the role of the superintendent and an undergraduate research assistant took on the role of the warden. Zimbardo designed the experiment in order to induce disorientation, depersonalization, and deindividuation in the participants.

The researchers held an orientation session for the guards the day before the experiment, during which guards were instructed not to harm the prisoners physically or withhold food or drink. In the footage of the study, Zimbardo can be seen talking to the guards: "You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me, and they'll have no privacy ... We're going to take away their individuality in various ways. In general what all this leads to is a sense of powerlessness. That is, in this situation we'll have all the power and they'll have none."[13]

The researchers provided the guards with wooden batons to establish their status,[14] clothing similar to that of an actual prison guard (khaki shirt and pants from a local military surplus store), and mirrored sunglasses to prevent eye contact. Prisoners wore uncomfortable, ill-fitting smocks and stocking caps, as well as a chain around one ankle. Guards were instructed to call prisoners by their assigned numbers, sewn on their uniforms, instead of by name.

The prisoners were "arrested" at their homes and "charged" with armed robbery. The local Palo Alto police department assisted Zimbardo with the simulated arrests and conducted full booking procedures on the prisoners, which included fingerprinting and taking mug shots. The prisoners were transported to the mock prison from the police station, where they were strip searched and given their new identities.

The small mock prison cells were set up to hold three prisoners each. There was a small corridor for the prison yard, a closet for solitary confinement, and a bigger room across from the prisoners for the guards and warden. The prisoners were to stay in their cells and the yard all day and night until the end of the study. The guards worked in teams of three for eight-hour shifts. The guards were not required to stay on-site after their shift.

Guards had differing responses to their new roles. One, described by Stanford Magazine as "the most abusive guard" felt his aggressive behavior was helping experimenters to get what they wanted. Another who had joined the experiment hoping to be selected as a prisoner, instead recalls "I brought joints with me, and every day I wanted to give them to the prisoners. I looked at their faces and saw how they were getting dispirited and I felt sorry for them,"[15] "Warden" David Jaffe intervened to change this guard's behavior, encouraging him to "participate" more and become more "tough."[16]

Results

After a relatively uneventful first day, on the second day the prisoners in Cell 1 blockaded their cell door with their beds and took off their stocking caps, refusing to come out or follow the guards' instructions. Guards from other shifts volunteered to work extra hours, to assist in subduing the revolt, and subsequently attacked the prisoners with fire extinguishers without being supervised by the research staff. Finding that handling nine cell mates with only three guards per shift was challenging, one of the guards suggested they use psychological tactics to control them. They set up a "privilege cell" in which prisoners who were not involved in the riot were treated with special rewards, such as higher quality meals. The "privileged" inmates chose not to eat the meal in commiseration with their fellow prisoners.

After only 35 hours, one prisoner began to act "crazy", as Zimbardo described: "#8612 then began to act crazy, to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control. It took quite a while before we became convinced that he was really suffering and that we had to release him." Guards forced the prisoners to repeat their assigned numbers[17] to reinforce the idea that this was their new identity. Guards soon used these prisoner counts to harass the prisoners, using physical punishment such as protracted exercise for errors in the prisoner count. Sanitary conditions declined rapidly, exacerbated by the guards' refusal to allow some prisoners to urinate or defecate anywhere but in a bucket placed in their cell. As punishment, the guards would not let the prisoners empty the sanitation bucket. Mattresses were a valued item in the prison, so the guards would punish prisoners by removing their mattresses, leaving them to sleep on concrete. Some prisoners were forced to be naked as a method of degradation. Several guards became increasingly cruel as the experiment continued; experimenters reported that approximately one-third of the guards exhibited genuine sadistic tendencies. Most of the guards were upset when the experiment was halted after only six days.

Zimbardo mentions his own absorption in the experiment. On the fourth day, some of the guards stated they heard a rumor that the released prisoner was going to come back with his friends and free the remaining inmates. Zimbardo and the guards disassembled the prison and moved it onto a different floor of the building. Zimbardo himself waited in the basement, in case the released prisoner showed up, and planned to tell him that the experiment had been terminated. The released prisoner never returned, and the prison was rebuilt in the basement.

Zimbardo argued that the prisoners had internalized their roles, since some had stated they would accept "parole" even if it would mean forfeiting their pay, despite the fact that quitting would have achieved the same result without the delay involved in waiting for their parole requests to be granted or denied.[18] Zimbardo argued they had no reason for continued participation in the experiment after having lost all monetary compensation, yet they did, because they had internalized the prisoner identity.

Prisoner No. 416, a newly admitted stand-by prisoner, expressed concern about the treatment of the other prisoners. The guards responded with more abuse. When he refused to eat his sausages, saying he was on a hunger strike, guards confined him to "solitary confinement", a dark closet: "the guards then instructed the other prisoners to repeatedly punch on the door while shouting at 416."[19] The guards said he would be released from solitary confinement only if the prisoners gave up their blankets and slept on their bare mattresses, which all but one refused to do.

Zimbardo aborted the experiment early when Christina Maslach, a graduate student in psychology whom he was dating (and later married),[20] objected to the conditions of the prison after she was introduced to the experiment to conduct interviews. Zimbardo noted that, of more than 50 people who had observed the experiment, Maslach was the only one who questioned its morality. After only six days of a planned two weeks duration, the experiment was discontinued.[18]

Conclusions

On August 20, 1971, Zimbardo announced the end of the experiment to the participants.

According to Zimbardo's interpretation of the SPE, it demonstrated that the simulated-prison situation, rather than individual personality traits, caused the participants' behavior. Using this situational attribution, the results are compatible with those of the Milgram experiment, where random participants complied with orders to administer seemingly dangerous and potentially lethal electric shocks to a shill.[21]

The experiment has also been used to illustrate cognitive dissonance theory and the power of authority.

Participants' behavior may have been shaped by knowing that they were watched (Hawthorne effect).[22] Instead of being restrained by fear of an observer, guards may have behaved more aggressively when supervisors observing them did not step in to restrain them.[21]

Zimbardo instructed the guards before the experiment to disrespect the prisoners in various ways. For example, they had to refer to prisoners by number rather than by name. This, according to Zimbardo, was intended to diminish the prisoners' individuality.[23] With no control, prisoners learned they had little effect on what happened to them, ultimately causing them to stop responding, and give up.[12] Quick to realize that the guards were the highest in the hierarchy, prisoners began to accept their roles as less important human beings.

One positive result of the study is that it has altered the way US prisons are run. For example, juveniles accused of federal crimes are no longer housed before trial with adult prisoners, due to the risk of violence against them.[22]

Shortly after the study was completed, there were bloody revolts at both the San Quentin and Attica prison facilities, and Zimbardo reported his findings on the experiment to the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary.

Criticism and response

There has been controversy over both the ethics and scientific rigor of the Stanford prison experiment since nearly the beginning, and it has never been successfully replicated.[6] French academic and filmmaker Thibault Le Texier, in a 2018 book about the experiment, Histoire d'un mensonge ("Story of a lie"), wrote that it could not be meaningfully described as an experiment and that there were no real results to speak of.[24] In response to criticism of his methodology, Zimbardo himself has agreed that the SPE was more of a "demonstration" than a scientific "experiment":

From the beginning, I have always said it's a demonstration. The only thing that makes it an experiment is the random assignment to prisoners and guards, that's the independent variable. There is no control group. There's no comparison group. So it doesn't fit the standards of what it means to be "an experiment." It's a very powerful demonstration of a psychological phenomenon, and it has had relevance.[25]

In 2018, in response to criticism by Le Texier and others, Philip Zimbardo wrote a detailed rebuttal on his website. In his summary, he wrote:

I hereby assert that none of these criticisms present any substantial evidence that alters the SPE's main conclusion concerning the importance of understanding how systemic and situational forces can operate to influence individual behavior in negative or positive directions, often without our personal awareness. The SPE's core message is not that a psychological simulation of prison life is the same as the real thing, or that prisoners and guards always or even usually behave the way that they did in the SPE. Rather, the SPE serves as a cautionary tale of what might happen to any of us if we underestimate the extent to which the power of social roles and external pressures can influence our actions.[26]

In turn, Le Texier published a peer-reviewed article which used videos, recordings, and notes from the experiment in Stanford University Archives to argue that "The guards knew what results the experiment was supposed to produce ... far from reacting spontaneously to this pathogenic social environment, the guards were given clear instructions for how to create it ... the experimenters intervened directly in the experiment, either to give precise instructions, to recall the purposes of the experiment, or to set a general direction ... in order to get their full participation, Zimbardo intended to make the guards believe that they were his research assistants."[27] Since this English-language publication, the debate has returned to the media in the United States.[28]

Treatment of "prisoners"

Some of the guards' behavior allegedly led to dangerous and psychologically damaging situations. According to Zimbardo's report, one third of the guards were judged to have exhibited "genuine sadistic tendencies", while many prisoners were emotionally traumatized, and three of them had to be removed from the experiment early. Zimbardo concluded that both prisoners and guards had become deeply absorbed in their roles and realized that he had likewise become as deeply absorbed in his own, and he terminated the experiment.[29]

Ethical concerns surrounding the experiment often draw comparisons to the similarly controversial experiment by Stanley Milgram, conducted ten years earlier in 1961 at Yale University, which studied obedience to authority.[21]

With the treatment that the guards were giving to the prisoners, the guards would become so deeply absorbed into their role as a guard that they would emotionally, physically and mentally humiliate the prisoners:

"Each prisoner was systematically searched and stripped naked. He was then deloused with a spray, to convey our belief that he may have germs or lice[...] Real male prisoners don't wear dresses, but real male prisoners do feel humiliated and do feel emasculated. Our goal was to produce similar effects quickly by putting men in a dress without any underclothes. Indeed, as soon as some of our prisoners were put in these uniforms they began to walk and to sit differently, and to hold themselves differently – more like a woman than like a man."[30]

These guards had taken their role seriously when Zimbardo had assigned them their role. The prisoners were stripped from their identity of who they are from the outside world, were given ID numbers and were only referred to by their numbers rather than their names. The paper reports a quote from a prisoner suggesting that this was effective: "I began to feel I was losing my identity."

Reliance on anecdotal evidence

Because of the nature of the experiment, Zimbardo found it impossible to keep traditional scientific controls in place. He was unable to remain a neutral observer, since he influenced the direction of the experiment as the prison's superintendent. Conclusions and observations drawn by the experimenters were largely subjective and anecdotal, and the experiment is practically impossible for other researchers to accurately reproduce. Erich Fromm claimed to see generalizations in the experiment's results and argued that the personality of an individual does affect behavior when imprisoned. This ran counter to the study's conclusion that the prison situation itself controls the individual's behavior. Fromm also argued that the amount of sadism in the "normal" subjects could not be determined with the methods employed to screen them.[31][32][33]

Coaching of "guards"

Carlo Prescott, who was Zimbardo's "prison consultant" during the experiment by virtue of having served 17 years in San Quentin for attempted murder, spoke out against the experiment publicly in a 2005 article he contributed to the Stanford Daily, after he had read about the various ways in which Zimbardo and others used the experiment to explain atrocities that had taken place in real prisons. In that article, entitled "The Lie of the Stanford Prison Experiment",[34] Prescott wrote:

[...] ideas such as bags being placed over the heads of prisoners, inmates being bound together with chains and buckets being used in place of toilets in their cells were all experiences of mine at the old "Spanish Jail" section of San Quentin and which I dutifully shared with the Stanford Prison Experiment braintrust months before the experiment started. To allege that all these carefully tested, psychologically solid, upper-middle-class Caucasian "guards" dreamed this up on their own is absurd. How can Zimbardo and, by proxy, Maverick Entertainment express horror at the behavior of the "guards" when they were merely doing what Zimbardo and others, myself included, encouraged them to do at the outset or frankly established as ground rules?

Like Zimbardo, Prescott has spoken before Congress on issues of prison reform.

(Zimbardo, in his 2018 response, wrote that, though Prescott attached his name to the article, it was in fact written by Hollywood writer/producer Michael Lazarou, who had unsuccessfully tried to get film rights to the Stanford prison experiment story, and when he was turned down began to publicly criticize it.[26])

In 2018, digitized recordings available on the official SPE website were widely discussed, particularly one where "prison warden" David Jaffe tried to influence the behavior of one of the "guards" by encouraging him to "participate" more and be more "tough" for the benefit of the experiment.[35][16] In his 2018 response, Zimbardo wrote that the instructions they gave to the guards were "mild compared to the pressure exerted by actual wardens and superior officers in real-life prison and military settings, where guards failing to participate fully can face disciplinary hearings, demotion, or dismissal."[26]

Implied demands by Zimbardo

The study was criticized in 2013 for demand characteristics by psychologist Peter Gray, who argued that participants in psychological experiments are more likely to do what they believe the researchers want them to do, and specifically in the case of the Stanford prison experiment, "to act out their stereotyped views of what prisoners and guards do."[36] Gray stated that he did not include the experiment in his introductory textbook, Psychology, because he thought it lacked scientific rigor.

"John Wayne" (the real-life Dave Eshelman), one of the guards in the experiment, said that he caused the escalation of events between guards and prisoners after he began to emulate a character from the 1967 film Cool Hand Luke. He further intensified his actions because he was nicknamed "John Wayne" by the other participants, even though he was trying to mimic actor Strother Martin, who had played the role of the sadistic prison Captain in the movie.[37] As he described it:

What came over me was not an accident. It was planned. I set out with a definite plan in mind, to try to force the action, force something to happen, so that the researchers would have something to work with. After all, what could they possibly learn from guys sitting around like it was a country club? So I consciously created this persona. I was in all kinds of drama productions in high school and college. It was something I was very familiar with: to take on another personality before you step out on the stage. I was kind of running my own experiment in there, by saying, "How far can I push these things and how much abuse will these people take before they say, 'knock it off?'" But the other guards didn't stop me. They seemed to join in. They were taking my lead. Not a single guard said, "I don't think we should do this."[15]

In his 2018 rebuttal, Zimbardo wrote that Eshelman's actions had gone "far beyond simply playing the role of a tough guard", and that his and the other guards' acts, given "their striking parallels with real-world prison atrocities", "tell us something important about human nature".[26]

Reporting and interpretation of outcome

Two students from the "prisoners" group left the experiment before it was terminated on the sixth day. Douglas Korpi was the first to leave, after 36 hours; he had a seeming mental breakdown in which he yelled "Jesus Christ, I'm burning up inside!" and "I can't stand another night! I just can't take it anymore!" His outburst was captured by a camera, and has become, in one commentator's words, "a defining moment" of the study.[6] In a 2017 interview, Korpi stated that his breakdown had been fake, and that he did it only so that he could leave and return to studying. (He had originally thought that he could study while "imprisoned", but the "prison staff" would not allow him.)[6] Zimbardo later stated that participants only had to state the phrase "I quit the experiment" in order to leave,[6] but transcripts from a taped conversation between Zimbardo and his staff show him stating "There are only two conditions under which you can leave, medical help or psychiatric."[24] In the 2017 interview, Korpi expressed regret that he had not filed a false imprisonment charge at the time.[6]

In his 2018 rebuttal, Zimbardo noted that Korpi's description of his actions had changed several times before the 2017 interview, and that in Zimbardo's 1992 documentary Quiet Rage Korpi had stated that the experiment "was the most upsetting experience of his life".[26]

Small and unrepresentative sample

Critics contend that not only was the sample size too small for extrapolation, but also having all of the experimental subjects be US male students gravely undercut the experiment's validity. In other words, it is conceivable that replicating the experiment using a diverse group of people (with different objectives and views in life)[22] would have produced radically distinct results.

Researchers from Western Kentucky University argued that selection bias may have played a role in the results. The researchers recruited students for a study using an advertisement similar to the one used in the Stanford Prison Experiment, with some ads saying "a psychological study" (the control group), and some with the words "prison life" as originally worded in Dr. Zimbardo's experiment. It was found that students who responded to the classified advertisement for the "prison life" were higher in traits such as social dominance, aggression, authoritarianism, etc. and were lower in traits related to empathy and altruism when compared to the control group participants.[38]

Ethical issues

The experiment was perceived by many to involve questionable ethics, the most serious concern being that it was continued even after participants expressed their desire to withdraw. Despite the fact that participants were told they had the right to leave at any time, Zimbardo did not allow this.[22]

Since the time of the Stanford Prison Experiment, ethical guidelines have been established for experiments involving human subjects.[39][40][41] The Stanford Prison Experiment led to the implementation of rules to preclude any harmful treatment of participants. Before they are implemented, human studies must now be reviewed and found by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) to be in accordance with ethical guidelines set by the American Psychological Association.[22] These guidelines involve the consideration of whether the potential benefit to science outweighs the possible risk for physical and psychological harm.

A post-experimental debriefing is now considered an important ethical consideration to ensure that participants are not harmed in any way by their experience in an experiment. Though Zimbardo did conduct debriefing sessions, they were several years after the Stanford prison experiment. By that time numerous details were forgotten; nonetheless, many participants reported that they experienced no lasting negative effects.[22] Current standards specify that the debriefing process should occur as soon as possible to assess what psychological harm, if any, may have been done and to rehabilitate participants, if necessary. If there is an unavoidable delay in debriefing, the researcher is obligated to take steps to minimize harm.[42]

With how the results of this experiment had ended, there have been some stir in ethical consequences involving this experiment. This study received much criticism with the lack of full consent from the participants with the knowledge from Zimbardo that he himself could not have predicted how the experiment would have turned out to be. With the participants playing the roles of prisoners and guards, there was no certain fact that they would get the help that they need in process of this study.[43] Zimbardo has come out to explain that he himself never thought his experiment would conclude how it did.

Comparisons to Abu Ghraib

When acts of prisoner torture and abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were publicized in March 2004, Zimbardo himself, who paid close attention to the details of the story, was struck by the similarity with his own experiment. He was dismayed by official military and government representatives' shifting the blame for the torture and abuses in the Abu Ghraib American military prison onto "a few bad apples" rather than acknowledging the possibly systemic problems of a formally established military incarceration system.

Eventually, Zimbardo became involved with the defense team of lawyers representing one of the Abu Ghraib prison guards, Staff Sergeant Ivan "Chip" Frederick. He was granted full access to all investigation and background reports, and testified as an expert witness in SSG Frederick's court martial, which resulted in an eight-year prison sentence for Frederick in October 2004.

Zimbardo drew from his participation in the Frederick case to write the book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, published by Random House in 2007, which deals with the similarities between his own Stanford Prison Experiment and the Abu Ghraib abuses.[19]

Similar studies

BBC prison study

Psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher conducted the BBC Prison Study in 2002 and published the results in 2006.[44] This was a partial replication of the Stanford prison experiment conducted with the assistance of the BBC, which broadcast events in the study in a documentary series called The Experiment. Their results and conclusions differed from Zimbardo's and led to a number of publications on tyranny, stress, and leadership. The results were published in leading academic journals such as British Journal of Social Psychology, Journal of Applied Psychology, Social Psychology Quarterly, and Personality and Social Psychology Review. The BBC Prison Study is now taught as a core study on the UK A-level Psychology OCR syllabus.

While Haslam and Reicher's procedure was not a direct replication of Zimbardo's, their study casts further doubt on the generality of his conclusions. Specifically, it questions the notion that people slip mindlessly into roles and the idea that the dynamics of evil are in any way banal. Their research also points to the importance of leadership in the emergence of tyranny of the form displayed by Zimbardo when briefing guards in the Stanford experiment.[45][46]

Experiments in the United States

The Stanford prison experiment was in part a response to the Milgram experiment at Yale beginning in 1961 and published in 1963.[47]

The Third Wave experiment involved the use of authoritarian dynamics similar to Nazi Party methods of mass control in a classroom setting by high school teacher Ron Jones in Palo Alto, California, in 1967 with the goal of demonstrating to the class in a vivid way how the German public in World War II could have acted in the way it did.[48] Although the veracity of Jones' accounts has been questioned, several participants in the study have gone on record to confirm the events.[49]

In both experiments, participants found it difficult to leave the study due to the roles they were assigned. Both studies examine human nature and the effects of authority. Personalities of the subjects had little influence on both experiments despite the test prior to the prison experiment.[50]

In the Milgram and the Zimbardo studies, participants conform to social pressures. Conformity is strengthened by allowing some participants to feel more or less powerful than others. In both experiments, behavior is altered to match the group stereotype.

In popular culture

The 2001 film Das Experiment starring Moritz Bleibtreu is based on the experiment. It was remade in 2010 as The Experiment

The 2015 film The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on the experiment.[51]

The YouTube series Mind Field (hosted by Michael Stevens) features an episode discussing the experiment.

Season 3, episode 2 of the television series Veronica Mars entitled "My Big Fat Greek Rush Week" features a similar experiment.

In The Overstory by Richard Powers, the fictional character Douglas Pavlicek is a prisoner in the experiment, an experience which shapes later decisions.

In episode 7 of television show Battleground, Political Machine, one of the characters divides a group of elementary school children into prisoners and guards.

In Season 15, Episode 11 of television show American Dad, American Data, Roger recruits Steve, Toshi, Snot and Barry into a similar experiment.

See also

Footnotes

- Victoria Bekiempis (August 4, 2015). "What Philip Zimbardo and the Stanford Prison Experiment Tell Us About Abuse of Power". Newsweek.

- "Intro to psychology textbooks gloss over criticisms of Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment". September 7, 2014.

- "Psychology Itself Is Under Scrutiny".

- "FAQ on official site". Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- Le Texier, Thibault (August 5, 2019). "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment". American Psychologist. 74 (7): 823–839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 31380664.

- Blum, Ben. "The Lifespan of a Lie – Trust Issues". Medium. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Slideshow on official site". Prisonexp.org. p. Slide 4. Archived from the original on May 12, 2000.

- "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Still powerful after all these years (1/97)". News.stanford.edu. August 12, 1996. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In the prison-conscious autumn of 1971, when George Jackson was killed at San Quentin and Attica erupted in even more deadly rebellion and retribution, the Stanford Prison Experiment made news in a big way. It offered the world a videotaped demonstration of how ordinary people, middle-class college students, can do things they would have never believed they were capable of doing. It seemed to say, as Hannah Arendt said of Adolf Eichmann, that normal people can take ghastly actions.

- Smith, J. R.; Haslam, S. A., eds. (2012). Social Psychology: Revisiting the Classic Studies. Sage.

- Saletan, William (May 12, 2004). "Situationist Ethics". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Haney, C.; Banks, W. C.; Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). "Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison". International Journal of Criminology and Penology. 1: 69–97.

- "Index of /downloads". zimbardo.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "C82SAD L07 Social Influence II The BBC Prison Experiment (handout)". Psychology.nottingham.ac.uk.

- Haney, C.; Banks, W. C. & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). "Research reviews" (PDF). Zimbardo.com.

- Ratnasar, Romesh (2011). "The Menace Within". Stanford Alumni Magazine. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In 1973, an investigation by the American Psychological Association concluded that the prison study had satisfied the profession's existing ethical standards. But in subsequent years, those guidelines were revised to prohibit human-subject simulations modeled on the SPE. "No behavioral research that puts people in that kind of setting can ever be done again in America," Zimbardo says.

- Van Bavel, J.J. (July 12, 2018). "Rethinking the 'nature' of brutality: Uncovering the role of identity leadership in the Stanford Prison Experiment". doi:10.31234/osf.io/b7crx. hdl:10023/18565.

The transcript of the meeting between Jaffe and Mark provides striking evidence that the Warden encouraged the Guard to discard his personal identity, to adopt a collective identity, and to embody stereotypic expectations associated with that collective identity

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Slide tour". The Stanford Prison Experiment.

- Zimbardo, P.G. (2007). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. New York: Random House.

- "The Lucifer Effect". lucifereffect.com.

- "The Standard Prison Experiment". Stanford University News Service.

- Konnikova, Konnikova (June 12, 2015). "The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment". New Yorker. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

Occasionally, disputes between prisoner and guards got out of hand, violating an explicit injunction against physical force that both prisoners and guards had read prior to enrolling in the study. When the "superintendent" and "warden" overlooked these incidents, the message to the guards was clear: all is well; keep going as you are. The participants knew that an audience was watching, and so a lack of feedback could be read as tacit approval. And the sense of being watched may also have encouraged them to perform.

- "Zimbardo – Stanford Prison Experiment | Simply Psychology". www.simplypsychology.org. Retrieved November 11, 2015.|quote=Zimbardo (1973) was interested in finding out whether the brutality reported among guards in American prisons was due to the sadistic personalities of the guards (i.e., dispositional) or had more to do with the prison environment (i.e., situational).

- Zimbardo (2007), The Lucifer Effect , p.54.

- Thibault Le Texier, Histoire d'un mensonge. Enquête sur l'expérience de Stanford, Paris: Zones, 2018, 296 p., ISBN 9782355221200.

- Resnick, Brian (June 28, 2018). "Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work". Vox. Retrieved July 9, 2018.|quote=From the beginning, I have always said it's a demonstration. The only thing that makes it an experiment is the random assignment to prisoners and guards, that's the independent variable. There is no control group. There's no comparison group. So it doesn't fit the standards of what it means to be "an experiment." It's a very powerful demonstration of a psychological phenomenon, and it has had relevance

- Philip Zimbardo’s Response To Recent Criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment, Stanford Prison Experiment website

- Thibault Le Texier, "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment." American Psychologist, Vol 74(7), Oct 2019, 823-839dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000401

- Rationally Speaking Episodes 241 - Thibault Le Texier on "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment http://rationallyspeakingpodcast.org/show/rs-241-thibault-le-texier-on-debunking-the-stanford-prison-e.html

- "Conclusion". Stanford Prison Experiment.

- "3. Arrival". Stanford Prison Experiment. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- "1971: Philip Zimbardo, Stanford Prison Experiment - precursor for Abu Ghraib torture. - AHRP". AHRP. December 28, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- Griggs, Richard A. (July 13, 2014). "Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in Introductory Psychology Textbooks". Teaching of Psychology. 41 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1177/0098628314537968. S2CID 145707676.

- "Fromm...on Zimbardo's Prison Experiment". angelfire.com. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

The purpose of the experiment was to study the behavior of normal people under a particular situation, that of playing the roles of prisoners and guards respectively, in a "mock prison." The general thesis that the authors believe is proved by the experiment is that many, perhaps the majority of people, can be made to do almost anything by the strength of the situation they are put in, regardless of their morals, personal convictions, and values (P. H. G. Zimbardo, 1972)

- "The Stanford Daily 28 April 2005 — The Stanford Daily". stanforddailyarchive.com. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- Masterson, Andrew (July 9, 2018). "New evidence shows Stanford Prison Experiment conclusions "untenable"". Cosmos. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

Archival recordings show one of the world's most famous psychology experiments was poorly designed – and its use to justify brutality baseless.

- Gray, Peter (2013). "Why Zimbardo's Prison Experiment Isn't in My Textbook". Freedom to Learn blog.

- "'John Wayne' (name withheld) Interview: 'The Science of Evil'". Primetime: Basic Instincts. KATU. January 3, 2007.

- Carnahan, Thomas; Sam McFarland (2007). "Revisiting the Stanford prison experiment: could participant self-selection have led to the cruelty?" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 33 (5): 603–14. doi:10.1177/0146167206292689. PMID 17440210. S2CID 15946975.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects

- The Belmont Report, Office of the Secretary, Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects for Biomedical and Behavioral Research, April 18, 1979

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, The Nuremberg Code

- American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, Sec. 8.07. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- "Stanford Prison Experiment | Simply Psychology". www.simplypsychology.org. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- "Welcome to the official site for the BBC Prison Study. Home - The BBC Prison Study". bbcprisonstudy.org.

- Interview of Alex Haslam at The Guardian

- Reicher, Steve; Haslam, Alex. "Learning from the Experiment". The Psychologist (Interview). Interviewed by Briggs, Pam. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- "Milgram Experiment | Simply Psychology". simplypsychology.org. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- Jones, Ron (1976). "The Third Wave". The Wave Home. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "Lesson Plan: The Story of the Third Wave (The Wave, Die Welle)". lessonplanmovie.com.

- "Comparing Milgram's Obedience and Zimbardo's Prison Studies". PSY 101 – Introduction to Psychology by Jeffrey Ricker, Ph.D. November 25, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Highfill, Samantha (July 17, 2015). "Billy Crudup turns college students into prison guards in The Stanford Prison Experiment". Entertainment Weekly.

References

- Haney, C.; Banks, W. C.; Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). "A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison". Naval Research Review. 30: 4–17.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2003). "Beyond Stanford: questioning a role-based explanation of tyranny". Dialogue (Bulletin of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology). 18: 22–25.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2006). "Stressing the group: social identity and the unfolding dynamics of responses to stress". Journal of Applied Psychology. 91 (5): 1037–1052. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1037. PMID 16953766. S2CID 14058651.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2012). "When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 16 (2): 154–179. doi:10.1177/1088868311419864. PMID 21885855. S2CID 30021002.

- Musen, K. & Zimbardo, P. G. (1991). Quiet rage: The Stanford prison study. Video recording. Stanford, CA: Psychology Dept., Stanford University.

- Reicher; Haslam, S. A. (2006). "Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study". British Journal of Social Psychology. 45 (Pt 1): 1–40. doi:10.1348/014466605X48998. PMID 16573869.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). "The power and pathology of imprisonment", Congressional Record (Serial No. 15, 1971-10-25). Hearings before Subcommittee No. 3, of the United States House Committee on the Judiciary, Ninety-Second Congress, First Session on Corrections, Part II, Prisons, Prison Reform and Prisoner's Rights: California. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). "Understanding How Good People Turn Evil." Interview transcript. Democracy Now!, March 30, 2007. Accessed January 17, 2015.

External links

- Stanford Prison Experiment, a website with info on the experiment and its impact

- Interviews with guards, prisoners, and researchers in July/August 2011 Stanford Magazine

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). From Heavens to Hells to Heroes. In-Mind Magazine.

- The official website of the BBC Prison Study

- "The Lie of the Stanford Prison Experiment", The Stanford Daily (April 28, 2005), p. 4 —Criticism by Carlo Prescott, ex-con and consultant/assistant for the experiment

- BBC news article – 40 years on, with video of Philip Zimbardo

- Philip G. Zimbardo Papers (Stanford University Archives)

- Photographs at cbsnews.com

Abu Ghraib and the experiment: