Guatemalan immigration to the United States

Migration by the numbers

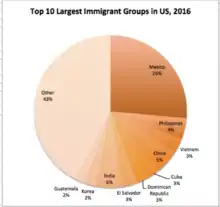

According to the 2010 US Census, the Guatemalan-born population totaled 1,044,209 people, comprising 2.1% of the overall immigrant population of the US, and making Guatemala the 10th highest sender of immigrants in the US.[1]

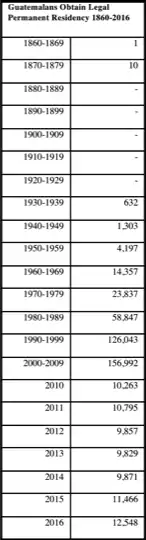

Up until the 1960s, Guatemalan migration to the US was negligible.[2] The Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Office of Immigration Statistics notes the first trickles of migration in the 1940s and 50s, but migration truly began to increase through the 1970s and 80s.[3] By the 1990s, more than 100,000 migrants were coming into the US by means of green cards each decade and then that number slightly dipped in the early 2000s.[3] More recent data is harder to gauge, as majority of Guatemalan migration is predicted to be unauthorized.[4] The US Census data in 2000 marked 372,487 Guatemalans in the US and by 2010, the number had reached over 1 million, showing a 183% increase in Guatemalans in the US over the decade. This shows that even though legal migration may have slowed, migration as a whole from the country is on the rise.[1]

Means of entry

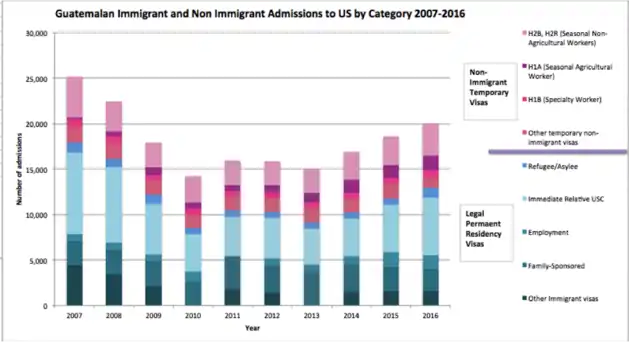

In the past decade, legal Guatemalan migration to the US has been predominantly through immediate relative petitions[5] and family sponsorship,[6] whereas "temporary" visas[7] have been granted primarily through the H2A and H1A programs for seasonal agricultural and non-agricultural labor.[8] These numbers are relatively small though (in 2016, about 13,000 Guatemalans were granted legal permanent residency, compared to about 174,500 Mexicans, Guatemala's neighbor, and about 7,500 Guatemalans were granted temporary work visas, compared to about 843,500 Mexicans).[8]

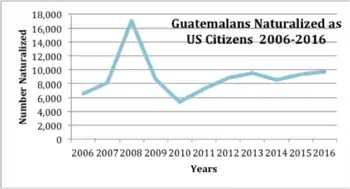

Very few Guatemalans have furthermore been granted citizenship. DHS data traces a range of about 6,500-9,700 Guatemalans granted citizenship annually since 2006.[9] In 2015, only 27% of the Guatemalans in the US were citizens.[10] Many Guatemalans, who are undocumented or on a temporary status, are blocked from a pathway to citizenship.[11] Facing immigration restrictions, such as the ceiling placed on relative-based immigration in the Immigration Act of 1990 and the massive amounts of border patrol that have increased through acts in 1996, 2001, 2005, and 2006, Guatemalans have predominantly had to enter the US without documentation.[12]

Furthermore, despite a recent spike in asylum claims, according to a 2017 report by the Center for Migration Studies, many Guatemalans with legitimate claims of persecution are being rejected and deported back to the situations of violence from which they had fled.[13] Asylum law depends on very specific instances of perception on the basis of race, religion, political opinion, nationality or membership in a social group in order to prove that one is a bona fide refugee and immigration attorneys have struggled to make the argument that being a victim of gang violence places a person in one of those categories. Furthermore, as many Guatemalans must claim their need for asylum at the border with minimal to no legal support in developing their claim, it is extremely difficult to win cases and many end up being subject to removal.[14] Despite the clear violence that more recent Guatemalan immigrants are fleeing (in 2014, Guatemala had the 9th highest murder rate in the world with 31.2 murders/100,000 residents) and the recent skyrocketing of asylum claims, the asylum grant rate has remained at an outrageously low 3-5%.[4]

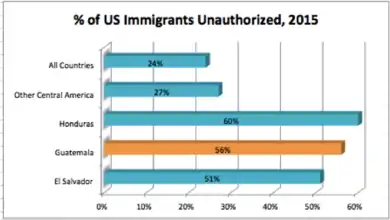

Fearful of this reality, many who can, end up entering the US via what the immigration theorist Philip Martin calls the "back door" route—entering unauthorized.[12] In fact, Pew Hispanic cites that in 2015, unauthorized migration made up the majority (56%) of Guatemalan migration, approximating 550,000 unauthorized Guatemalan immigrants that year.[4] Some Guatemalans have qualified for the program of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) since the Obama Administration instituted it in 2012, but Pew Hispanic estimates that only about 17,700 Guatemalans satisfied the requirements to receive DACA status, which is currently being contested by the Trump administration.

Geographic destinations

Guatemalans have primarily settled in California, Florida and Texas. As of 2015, 29% of Guatemalans in the US lived in California while 8% respectively lived in Florida and Texas.[4] Within California, Guatemalans are concentrated in Los Angeles (20%).[4] Within these cities, ethnic enclaves and already-present communities help receive new migrants, connecting them with jobs and easing the transition, thus decreasing the linguistic and cultural costs of migration.

References

- U.S. Census Bureau, “The Hispanic Population: 2010,” Hispanic or Latino Origin Population by Type: 2000 and 2010 Table 1. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-04.pdf. (Accessed Feb 11, 2018).

- "Table 1. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status: Fiscal Years 1820 To 2016". Department of Homeland Security. 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- Department of Homeland Security, “Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Region and Selected Country of Last Residence: Fiscal Years 1860-2016.”

- D’Vera Cohn, Jeffrey Passel, and Ana Golzalez-Barrera. "Rise in US Migration from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras Outpaces Growth from Elsewhere,” Pew Hispanic, Dec 7, 2017.

- Bureau, US Census. "Hispanic Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- USCIS (2015-07-14). "Family of Greencard Holders". US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

- "Temporary Worker Visas". travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- Department of Homeland Security. “Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status By Broad Class of Admission and Region and Country of Birth.” And “Nonimmigrant Temporary Worker Admissions (I-94 Only) By Country Of Citizenship.” Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2007-2016.

- Department of Homeland Security. “Persons naturalized by Region/ Country of Birth and Selected Characteristics.” Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2016 .

- Jeanne Batalova and Gabriel Lesser. “Central American Immigrants in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute. April 5, 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states

- USCIS. "Who Is Eligible for Naturalization?" (PDF). US Citizenship and Naturalization Services.

- Philip L Martin. “United States.” In Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, 3rd edition, James Hollifield, Philip L. Martin and Pia Orrenius (eds.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014.

- Point of No Return: The Fear and Criminalization of Central American Refugees. New York: Center for Migration Studies and Cristosal, June 2017. http://cmsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/CMS-Cristosal-Report-final.pdf.

- Jonathan Jacobs and Andrew Schoenholtz. “The State of Asylum Representation: Ideas for Change.” Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 16 (2002): 739.