Gustav von Schmoller

Gustav Friedrich (after 1908: von) Schmoller (German: [ˈʃmɔlɐ] (![]() listen); 24 June 1838 – 27 June 1917) was the leader of the "younger" German historical school of economics.

listen); 24 June 1838 – 27 June 1917) was the leader of the "younger" German historical school of economics.

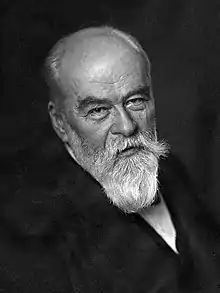

Gustav von Schmoller | |

|---|---|

Gustav von Schmoller by Nicola Perscheid c. 1908 | |

| Born | 24 June 1838 Heilbronn, Germany |

| Died | 27 June 1917 (aged 79) Bad Harzburg, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Field | Economics |

| School or tradition | Historical school of economics |

| Influences | Karl Wolfgang Christoph Schüz |

| Contributions | Inductive approach to economics |

He was a leading Sozialpolitiker (more derisively, Kathedersozialist, "Socialist of the Chair"), and a founder and long-time chairman of the Verein für Socialpolitik, the German Economic Association, which continues to exist.[1]

The appellation "Kathedersozialist" was given to Schmoller and other members of the Verein by their enemies. Schmoller disavowed the "socialist" label, instead tracing his thought to the heterodox liberalism represented by Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi, John Stuart Mill, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, Bruno Hildebrand, Thomas Edward Cliffe Leslie, Lorenz von Stein, and Émile de Laveleye and radicals such as Frederic Harrison and Edward Spencer Beesly.[2] His goal was to reconcile the Prussian monarchy and bureaucracy "with the idea of the Liberal state and complemented by the best elements of parliamentarianism" to carry out social reform.[2][3]

Life

Schmoller was born in Heilbronn. His father was a Württemberg civil servant. Young Schmoller studied Kameralwissenschaft (a combination of economics, law, history, and civil administration) at the University of Tübingen (1857–61). In 1861, he obtained an appointment at the Württemberg Statistical Department.[4] During his academic career, he held appointments as a professor at the universities of Halle (1864–72), Strasbourg (1872–82), and Berlin (1882–1913).[5] After 1899, he represented the University of Berlin in the Prussian House of Lords.

Schmoller's influence on academic policy, economic, social and fiscal reform, and economics as an academic discipline for the time between 1875 and 1910[6] can hardly be overstated. He was an outspoken proponent of the assertion of German naval power and the expansion of the German overseas empire.

Work

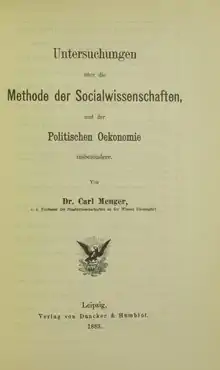

As an outspoken leader of the "younger" historical school, Schmoller opposed what he saw as the axiomatic-deductive approach of classical economics and, later, the Austrian school—indeed, Schmoller coined the term to suggest provincialism in an unfavorable review of the 1883 book Investigations into the Method of the Social Sciences with Special Reference to Economics (Untersuchungen über die Methode der Socialwissenschaften und der politischen Oekonomie insbesondere) by Carl Menger, which attacked the methods of the historical school. This led to the controversy known as the Methodenstreit, which today often appears as a waste of energies and one of the main reasons for the later demise of the whole historical school, although—as Joseph Schumpeter once pointed out—this was really a quarrel within that school. Schmoller's primarily inductive approach, requesting careful study, comparative in time and space,[6] of economic performance and phenomena generally, his focus on the evolution of economic processes and institutions, and his insistence on the cultural specificity of economics and the centrality of values in shaping economic exchanges stand in stark contrast to some classical and most neoclassical economists, so that he and his school fell out of the mainstream of economics by the 1930s, being replaced in Germany by the successor Freiburg school.

However, it is often overlooked that Schmoller's primary preoccupation in his lifetime was not with economic method but with economic and social policy to address the challenges posed by rapid industrialization and urbanization. That is, Schmoller was first and foremost a social reformer.[7] As such, Schmoller's influence extended throughout Europe, to the Progressive movement in the United States, and to social reformers in Meiji Japan. His most prominent non-German students and followers included William J. Ashley, W.E.B. Du Bois, Richard T. Ely, Noburu Kanai, Albion W. Small, and E.R.A. Seligman.

Since the 1980s, Schmoller's work has been re-evaluated and found relevant to some branches of heterodox economics, especially development economics, behavioral economics, evolutionary economics, and neo-institutional economics. He has long had an influence within the subfield of economic history and the discipline of sociology.

- Works by Schmoller

His works, the majority of which deal with economic history and policy, include:

- Der französiche Handelsvertrag und seine Gegner (The French trade treaty and its opponents, 1862)

- Zur geschichte der deutschen Kleingewerbe im 19. Jahrhundert (History of German Small Businesses in the 19th Century, 1870)

- Strassburg zur Zeit der Zunftkämpfe (Strassburg During the Guild Fights, 1875)

- Zur Litteraturgeschichte der Staats- und Sozialwissenschaften (1888)

- Umrisse und Untersuchungen zur Verfassungs-, Verwaltungs-, und Wirtschaftsgeschichte (1898)

- Grundriss der allgemeinen Volkswirthschaftslehre (Layout of General Economics, 1900–1904)

- Ueber einige Grundfragen der Sozialpolitik (About a few Questions of Social Politics, 1904)

After 1881, Schmoller was editor of the Jahrbuch für Gesetzebung, Verwaltung, und Volkswirthschaft im deutschen Reich. From 1878 to 1903, he edited a series of monographs entitled Staats- und sozialwissenschaftliche Forschungen. He was also an editor and major contributor to Acta Borussica, an extensive collection of Prussian historical sources undertaken by the Berlin Academy of Science upon Schmoller's and Sybel's instigation.

One of the reasons why Schmoller is not more widely known today is that most of his books and articles were not translated,[1] as during his time Anglo-American economists generally read German, which was the dominant scholarly language of the time. German having fallen out of favor, the untranslated texts are now inaccessible to readers without knowledge of German. Two exceptions are:

- The Mercantile System and Its Historical Significance, New York: Macmillan, 2nd ed. 1910. This is a chapter from Schmoller's much larger work Studien über die wirtschaftliche Politik Friedrichs des Grossen which was published in 1884. The chapter was translated by William J. Ashley and published in 1897 under the English title above. online edition

- "The Idea of Justice in Political Economy." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 4 (1894): 697–737. in JSTOR

His magnum opus is

- Grundriss der allgemeinen Volkswirtschaftslehre,[1] Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1900–1904.

- Important recent books on Schmoller in English

- Backhaus, Jürgen G. (1994), ed. Gustav Schmoller and the Problems of Today. History of Economic Ideas, vol.s I/1993/3, II/1994/1.

- Backhaus, Jürgen G. (1997), ed. Essays in Social Security and Taxation. Gustav von Schmoller and Adolph Wagner Reconsidered. Marburg: Metropolis.

- Balabkins, Nicholas W. (1988). Not by theory alone...: The Economics of Gustav von Schmoller and Its Legacy to America. Berlin: Duncker u. Humblot.

- Grimmer-Solem, Erik (2003). The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany, 1864–1894. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Koslowski, Peter, ed. The Theory of Ethical Economy in the Historical School. Wilhelm Roscher, Lorenz v. Stein, Gustav Schmoller, Wilhelm Dilthey and Contemporary Thought. Berlin etc.: Springer.

- Shionoya, Yuichi (2001), ed. The German Historical School: The Historical and Ethical Approach to Economics. London etc.: Routledge.

See also

Notes

- Bonn, M.J. (1938). "Gustav Schmoller und die Volkswirtschaftslehre". The Economic Journal. 48 (192): 713–714. doi:10.2307/2225060. JSTOR 2225060.

- Grimmer-Solem, Erik (2003). The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany, 1864-1894. Clarendon Press. pp. 197–198.

- Nau, Heino Heinrich (2000). "Gustav Schmoller's Historico-Ethical Political Economy : ethics, politics and economics in the younger German Historical School, 1860-1917". European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 7 (4): 523. doi:10.1080/09672560050210098. S2CID 154920944.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Encyclopedia of Law and Society: American and Global Perspectives, 3rd ed., "Schmoller, Gustav von."

- Powers, Charles H. (1995). "Review". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 54 (3): 287–288. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1995.tb03427.x. JSTOR 3487093.

- Grimmer-Solem, Erik (2003) The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany, 1864–1894 (Oxford: Oxford University Press.

References

- Clark, David S. Encyclopedia of Law and Society American and Global Perspectives . Minneapolis: Sage Publications, Inc, 2007.

- Grimmer-Solem, Erik. The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany, 1864–1894. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Iggers, Georg G. Historiography in the Twentieth Century: From Scientific Objectivity to the Postmodern Challenge (Wesleyan University Press, 1997).

- Richter, Rudolf. "Bridging Old and New Institutional Economics: Gustav Schmoller, the Leader of the Younger German Historical School, Seen With Neoinstitutionalists' Eyes," Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft Vol. 152, No. 4 (December 1996), pp. 567–592 (in JSTOR).

- Shionoya, Yuichi. The Soul of The German Historical School: Methodological Essays on Schmoller, Weber and Schumpeter New York: Springer, 2005.

- Veblen, Thorstein. "Gustav Schmoller's Economics," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 16 no. 1 (Nov. 1901): 69–93 (in JSTOR).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gustav Schmoller. |