HMS Iron Duke (1912)

HMS Iron Duke was a dreadnought battleship of the Royal Navy, the lead ship of her class, named in honour of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. She was built by Portsmouth Dockyard, and her keel laid in January 1912. Launched ten months later, she was commissioned into the Home Fleet in March 1914 as the fleet flagship. She was armed with a main battery of ten 13.5-inch (340 mm) guns and was capable of a top speed of 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph).

HMS Iron Duke in 1914 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Iron Duke |

| Namesake: | Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington |

| Builder: | Portsmouth Dockyard |

| Laid down: | 12 January 1912 |

| Launched: | 12 October 1912 |

| Commissioned: | March 1914 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, March 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Iron Duke-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 622 ft 9 in (189.81 m) o/a |

| Beam: | 90 ft (27.4 m) |

| Draught: | 29 ft 6 in (8.99 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21.25 kn (24.5 mph; 39.4 km/h) |

| Range: | 7,800 nmi (8,976 mi; 14,446 km) at 10 kn (11.5 mph; 18.5 km/h) |

| Complement: | 995–1,022 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

Iron Duke served as the flagship of the Grand Fleet during the First World War, including at the Battle of Jutland. There, she inflicted significant damage on the German battleship SMS König early in the main fleet action. In January 1917, she was relieved as fleet flagship. After the war, Iron Duke operated in the Mediterranean as the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet. She participated in both the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War in the Black Sea and the Greco-Turkish War. She also assisted in the evacuation of refugees from Smyrna. In 1926, she was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, where she served as a training ship.

Iron Duke remained on active duty for only a few more years; in 1930, the London Naval Treaty specified that the four Iron Duke-class battleships be scrapped or otherwise demilitarised. Iron Duke was therefore converted into a gunnery training ship; her armour and much of her armament was removed to render her unfit for combat. She served in this capacity until the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, when she was moored in Scapa Flow as a harbour defence ship. In October, she was badly damaged by German bombers and was run aground to avoid sinking. She continued to serve as an anti-aircraft platform for the duration of the war, and was eventually refloated and broken up for scrap in the late 1940s.

Design

The four Iron Duke-class battleships were ordered in the 1911 building programme, and were an incremental improvement over the preceding King George V class. The primary change between the two designs was the substitution of a heavier secondary battery in the newer vessels. Iron Duke was 622 feet 9 inches (190 m) long overall and had a beam of 90 ft (27 m) and an average draught of 29 ft 6 in (9 m). She displaced 25,000 long tons (25,401 t) as designed and up to 29,560 long tons (30,034 t) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of four Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by eighteen Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The engines were rated at 29,000 shaft horsepower (21,625 kW) and produced a top speed of 21.25 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph). Her cruising radius was 7,800 nautical miles (14,446 km; 8,976 mi) at a more economical 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph). Iron Duke had a crew of 995 officers and ratings, though during wartime this grew to up to 1,022.[1]

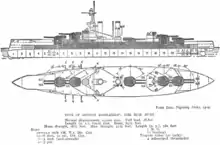

Iron Duke was armed with a main battery of ten BL 13.5-inch (343 mm) Mk V naval guns mounted in five twin gun turrets. They were arranged in two superfiring pairs, one forward and one aft; the fifth turret was located amidships, between the funnels and the rear superstructure. Close-range defence against torpedo boats was provided by a secondary battery of twelve BL 6-inch Mk VII guns. The ship was also fitted with a pair of QF 3-inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft guns and four 47 mm (2 in) 3-pounder guns.[Note 1] As was typical for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with four 21 in (530 mm) torpedo tubes submerged on the broadside.[1]

Iron Duke was protected by a main armoured belt that was 12 in (305 mm) thick over the ship's ammunition magazines and engine and boiler rooms, and reduced to 4 in (102 mm) toward the bow and stern. Her deck was 2.5 in (64 mm) thick in the central portion of the ship, and reduced to 1 in (25 mm) elsewhere. The main battery turret faces were 11 in (279 mm) thick, and the turrets were supported by 10 in (254 mm) thick barbettes.[1]

Service history

Iron Duke was laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard on 12 January 1912 and launched on 12 October of that year. After completing fitting-out work, she began sea trials on 25 November 1913.[2] The ship was completed in March 1914,[1] and she joined the Home Fleet after completing her trials. In the Home Fleet, she served as the flagship of Admiral Sir George Callaghan.[3] On 29 July 1914, as war loomed on the Continent, Iron Duke and the rest of the Home Fleet was ordered to proceed to Scapa Flow from Portland to safeguard the fleet from a possible German surprise attack.[4]

World War I

In August 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet; Iron Duke remained the flagship of the fleet, now under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe.[3] On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Iron Duke stood with the main body in support of Vice Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.[5] Iron Duke and most of the fleet initially remained in port during the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914, though the 3rd Battle Squadron was sent to reinforce the British forces in the area. After receiving further information about the possibility of the rest of the German fleet being at sea, Jellicoe gave the order for the fleet to sortie to try to intercept the Germans, though by that time they had already retreated.[6] Iron Duke went to sea with the 2nd and 4th Battle Squadrons for gunnery practice north of the Hebrides on 23 and 24 December.[7] The following day, the rest of the fleet joined Iron Duke for a sweep in the North Sea, which concluded on 27 December.[8]

_2.jpg.webp)

Iron Duke and the rest of the fleet conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney and Shetland.[9] On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet, but Iron Duke and the rest of the fleet did not become engaged in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day.[10] Upon returning from the operation, Iron Duke went to Invergordon for refit; while she was away, HMS Centurion acted as the temporary fleet flagship.[11] The work was completed by 23 February, after which she returned to Scapa Flow.[12] On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March.[13] On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[14]

The Grand Fleet conducted a sweep into the central North Sea on 17–19 May without encountering any German vessels.[15] On 25 May, Iron Duke carried Jellicoe to Rosyth to meet with Admiral Henry Jackson, the new First Sea Lord. Iron Duke returned to Scapa Flow on 28 May, in time to participate in another sweep into the North Sea on 29–31 May.[16] After returning to Scapa Flow, Iron Duke immediately departed for Cromarty.[17] The fleet conducted gunnery training in mid-June.[18] Iron Duke, the 2nd Battle Squadron, and the 1st Cruiser Squadron conducted gunnery training at Cromarty on 2 August; after completing the drills, the ships returned to Scapa Flow. On 7 August, the ship again took Jellicoe to Cromarty for another meeting, this time with the Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith.[19] Iron Duke was back in Scapa Flow by 16 August.[20]

On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills.[21] Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises.[22] Iron Duke went to Invergordon on 1 October for another period of refitting—the work lasted until 11 October.[23] Two days later, the majority of the fleet conducted another sweep into the North Sea, returning to port on 15 October.[24] On 2–5 November, Iron Duke participated in another fleet training operation west of the Orkneys.[25] Another such cruise took place on 1–4 December.[26] Later in the month, Iron Duke took part in gunnery drills, and during them, conducted an experiment of sorts to determine the accuracy of the ship's gunners. Jellicoe concluded that the "result was very satisfactory."[27]

Iron Duke collided with the tanker Prudentia on 12 January 1916 while in Scapa Flow, and the latter sank.[28] The tanker had come loose during a severe gale, which had winds of up to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). Iron Duke was undamaged in the accident. The typical routine of gunnery drills and squadron exercises occurred in January.[29] The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea.[30] On the night of 25 March, Iron Duke and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support the Battlecruiser Fleet and other light forces that raided the German zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a severe gale threatened the light craft. Iron Duke guided the destroyers back to Scapa while the rest of the fleet retired independently.[31]

On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea.[32] The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft. The Grand Fleet did not arrive in the area until after the Germans had withdrawn, however.[33][34] On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[35]

Battle of Jutland

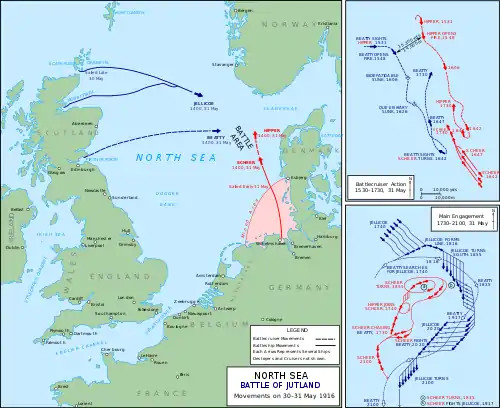

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the German High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts, six light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats, departed the Jade early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers and supporting cruisers and torpedo boats.[36] The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. The Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[37] On the day of the battle, Iron Duke steamed with the 4th Battle Squadron, and was the 9th ship in the British line.[38]

The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battlecruiser formations in the afternoon,[39] but by 18:00, the Grand Fleet approached the scene. At around 18:14, two large-calibre shells fell near Iron Duke but caused no damage.[40] Fifteen minutes later, Iron Duke had closed to effective gunnery range—some 26,000 yards (24,000 m)—of the German fleet, and took the dreadnought SMS König under fire. Iron Duke's first salvo fell short, but the next three were on target; the ship's gunner claimed at least six hits on the German battleship.[41] In fact, they had scored seven hits on König and inflicted significant damage.[42]

Shortly after 19:00, fighting around the disabled German cruiser SMS Wiesbaden—which had been badly damaged earlier in the engagement—resumed. Iron Duke opened fire on the crippled cruiser and nearby destroyers with her secondary battery at 19:11 at a range of 9,000 to 10,000 yards (8,200 to 9,100 m). Iron Duke's gunners claimed to have sunk one of the destroyers and hit a second, but they had in fact missed their targets entirely.[43] Shortly thereafter, the German destroyers attempted to launch a torpedo attack on the British line; Iron Duke began firing at 19:24. The sinking of the destroyer SMS S35 is credited to a salvo from Iron Duke, but determining which ship fired which shells in the melee is difficult, according to naval historian John Campbell.[44]

Following the German destroyer attack, the High Seas Fleet disengaged, and Iron Duke and the rest of the Grand Fleet saw no further action in the battle. This was, in part, due to confusion aboard Iron Duke over the exact location and course of the German fleet; without this information, Jellicoe could not bring his fleet to action.[45] At 21:30, the Grand Fleet began to reorganise into its nighttime cruising formation.[46] Early on the morning of 1 June, the Grand Fleet combed the area, looking for damaged German ships, but after spending several hours searching, they found none.[47] Iron Duke returned to Scapa Flow, arriving at 11:30.[48] Over the course of the battle, Iron Duke had fired ninety rounds from her main battery,[49] along with fifty rounds from her secondary guns.[50]

Subsequent actions in the North Sea

On 18 August, the Germans again sortied, this time to bombard Sunderland; Scheer hoped to draw out Beatty's battlecruisers and destroy them. British signals intelligence decrypted German wireless transmissions, allowing Jellicoe enough time to deploy the Grand Fleet in an attempt to engage in a decisive battle. Both sides withdrew, however, after their opponents' submarines inflicted losses: the British cruisers Nottingham and Falmouth were both torpedoed and sunk by German U-boats, and the German battleship SMS Westfalen was damaged by the British submarine E23. After returning to port, Jellicoe issued an order that prohibited risking the fleet in the southern half of the North Sea due to the overwhelming risk from mines and U-boats unless the odds of defeating the High Seas Fleet in a decisive engagement were high.[51]

In the aftermath of Jutland, the Royal Navy determined that horizontal protection, particularly over ammunition magazines, was insufficient. As a result, many ships in the Grand Fleet had additional armour installed; Iron Duke went into dock for this work in October. The work, which saw over 100 long tons (100 t) of armour added to the ship, was completed by December.[52] On 28 November 1916, while she was still in dry dock, Admiral Beatty replaced Jellicoe as the commander of the Grand Fleet; Iron Duke served as his flagship until January 1917, when he transferred to Queen Elizabeth.[28] In 1918, flying-off platforms for aircraft were installed on Iron Duke's "B" and "Q" turrets.[53]

Post-war career

In March 1919, Iron Duke was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet, where she again served as flagship. The ship went into the Black Sea in April to participate in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.[28] While en route, the ship stopped in Constantinople on 7 April.[54] There, Iron Duke was involved in the destruction of warships and other materiel that might be used by the Bolsheviks.[55] On 12 May, Iron Duke travelled from Constantinople to Smyrna, where she provided a landing party to occupy some of the city's outer forts.[56] She returned to the Black Sea, where she remained until June, when she returned to the Mediterranean.[28]

Iron Duke returned to the Black Sea in late 1919. She arrived in Novorossiysk on 12 October, where she met the White Russian protected cruiser General Kornilov.[57] On 14 October, the ship stopped in Sevastopol.[58] Iron Duke returned to Novorossiysk on 19 January 1920.[59] On 25 January, she stopped in the ports of Yalta and Sevastopol to inspect the situation of the White Russians there.[60] On 17 June, shore parties from Iron Duke and the destroyer Shark destroyed Turkish guns in the forts protecting the Bosporus on the Black Sea.[61]

On 2 September 1922, Iron Duke was steaming to the Dalmatian coast for a training cruise, when she received news of the Greek defeat in Turkey. Admiral Osmond Brock, the Mediterranean Fleet commander, ordered Iron Duke to proceed to Smyrna, where he expected disturbances.[62] There, she served as the flagship of the British naval forces participating in the evacuation of Greek refugees from the city. She was present during the Great Fire that devastated the city.[28] During the chaos, a number of refugees managed to come alongside Iron Duke in small boats, and were brought aboard the battleship.[63] The following month, the Allies held a conference aboard Iron Duke at Mudania to mediate the Greco-Turkish dispute.[28] The ship thereafter proceeded to Constantinople.[64]

In November 1924, Queen Elizabeth relieved Iron Duke as the Mediterranean Fleet flagship; Iron Duke was then transferred to the 3rd Battle Squadron, Mediterranean Fleet, where she became the squadron flagship. The 3rd Squadron was moved to the Atlantic Fleet in March 1926, where it was used as a training squadron. Iron Duke remained the squadron flagship during this period, until 30 May 1928, when she was relieved by her sister Benbow.[28] In 1927, the Navy considered adding anti-torpedo bulges to Iron Duke and her sister ships, but the plan was discarded because the ships were due to be replaced in 1931–1932 under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 and the plan was not economical.[65] That year, the aircraft launching-platform mounted on Iron Duke's "B" turret was removed. The ship went into dry dock in May 1928 for a periodic refit; the work lasted until May 1929. Two 4 in (100 mm) anti-aircraft guns were installed on the forward superstructure. The aircraft platform on "Q" turret was also removed during this period.[66]

Iron Duke returned to service on 30 May 1929, when she was recommissioned as a gunnery training ship. She served in this capacity for only a year and a half, however.[28] In November 1931, under the terms of the London Naval Treaty, Iron Duke was disarmed and converted into a gunnery training vessel. The work lasted until 21 September 1932, when she was commissioned for new sea trials. The ship's "B" and "Y" turrets were also removed, and several small guns of various types were installed atop "B" barbette. Two 4.7 in (120 mm) anti-aircraft guns were installed as well, but these were later removed in 1935. A high-angle director for the anti-aircraft guns was also added in place of the aft rangefinder. Over 2,500 long tons (2,500 t) of steel from her belt armour was removed during the demilitarisation; in all, 4,258 long tons (4,326 t) of material was removed from the ship and 202 long tons (205 t) added.[65] The ship was recommissioned on 4 October 1932 at Devonport, again as a gunnery training ship.[28] She was featured in the film Brown on Resolution, which was released in May 1935.[67] On 16 July 1935, she was present at the Silver Jubilee Fleet Review at Spithead for King George V. She attended another Fleet Review, the coronation review for George VI, on 20 May 1937.[28] In 1939, a twin QF 5.25-inch dual-purpose gun mount was installed aft of "Y" barbette.[65]

Second World War

During the Second World War, she was used as a base ship and a floating anti-aircraft platform at Scapa Flow.[28] Her secondary guns were removed and used for coastal defence around the base.[3] On 17 October 1939, four Junkers Ju 88 medium bombers attacked Scapa Flow, and damaged Iron Duke with several near misses. To prevent her from sinking, her crew had to run the ship aground.[68] On 16 March 1940 the ship, which was still beached, was attacked again by Luftwaffe aircraft. This time, eighteen Ju 88s attacked the harbour and surrounding installations. Iron Duke was again badly damaged, as was the heavy cruiser Norfolk.[69]

The ship's presence in Scapa Flow may have affected the Germans' plans during Operation Rheinübung, the Atlantic sortie of the battleship Bismarck in May 1941. German aerial reconnaissance spotted Iron Duke and two decoy battleships, merchant ships that had been camouflaged with wood and canvas to look like Revenge-class battleships, in the harbour, and erroneously identified them as active units of the Home Fleet. Under the mistaken impression that the heavy units of the Home Fleet were still in port, the German fleet commander, Günther Lütjens, decided to break into the Atlantic via the Denmark Strait, which resulted in the Battle of the Denmark Strait.[70]

The ship was later repaired and returned to service as a harbour ship for the duration of the war, though she remained beached.[3] Iron Duke remained in the Royal Navy inventory until March 1946, when she was sold for scrapping to Metal Industries, still beached in Scapa Flow.[1][28] The ship was refloated on 19 April 1946 and transferred to Faslane on 19 August. In September 1948, she was re-sold and moved to Glasgow, arriving on 30 November 1948, and subsequently broken up for scrap.[28][71] Iron Duke's bell is on display at Winchester Cathedral.[72]

Footnotes

Notes

- "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

Citations

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 31

- Burt, p. 216

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 32

- Massie, p. 19

- Jellicoe, pp. 163–165

- Jellicoe, pp. 177–179

- Jellicoe, p. 182

- Jellicoe, pp. 183–184

- Jellicoe, p. 190

- Jellicoe, pp. 194–196

- Jellicoe, p. 197

- Jellicoe, p. 200

- Jellicoe, p. 206

- Jellicoe, pp. 211–212

- Jellicoe, p. 217

- Jellicoe, pp. 218–219

- Jellicoe, p. 220

- Jellicoe, p. 221

- Jellicoe, pp. 234–236

- Jellicoe, p. 241

- Jellicoe, p. 243

- Jellicoe, p. 246

- Jellicoe, p. 252

- Jellicoe, p. 250

- Jellicoe, p. 253

- Jellicoe, pp. 257–258

- Jellicoe, pp. 260–261

- Burt, p. 231

- Jellicoe, pp. 267–269

- Jellicoe, p. 271

- Jellicoe, pp. 279–280

- Jellicoe, p. 284

- Jellicoe, pp. 286–287

- Marder, p. 424

- Jellicoe, pp. 288–290

- Tarrant, p. 62

- Tarrant, pp. 63–64

- Campbell, p. 16

- Campbell, p. 37

- Campbell, pp. 121–122

- Campbell, p. 156

- Campbell, pp. 188–191

- Campbell, p. 210

- Campbell, p. 212

- Campbell, p. 256

- Campbell, p. 274

- Campbell, pp. 309–310

- Campbell, p. 322

- Campbell, p. 346

- Campbell, p. 358

- Massie, pp. 682–684

- Burt, p. 215

- Burt, p. 218

- Halpern, p. 33

- Halpern, p. 47

- Halpern, pp. 67, 74

- Halpern, p. 114

- Halpern, p. 115

- Halpern, p. 143

- Halpern, p. 148

- Halpern, p. 250

- Halpern, p. 376

- Halpern, p. 381

- Halpern, p. 403

- Burt, pp. 221, 223

- Burt, p. 220

- Mackenzie, p. 17

- Rohwer, p. 7

- Rohwer, p. 17

- Zetterling & Tamelander, pp. 137–140

- Colledge & Warlow, p. 198

- Goldsmith, p. 2

References

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1558217592.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2010). Ships of the Royal Navy. Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781612000275.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Goldsmith, Robert Frederick Kinglake (1974). The Military Memorials of Winchester Cathedral. Winchester, UK: Friends of Winchester Cathedral. ISBN 0903346052.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2011). The Mediterranean Fleet, 1919–1929. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409427568.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York, NY: George H. Doran Company.

- Mackenzie, S. P. (2001). British War Films, 1939–1945: The Cinema and the Services. London: Hambledon and London. ISBN 0-826-44644-2.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1965). Volume II: The War Years to the eve of Jutland: 1914–1916. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. Oxford University Press.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345408780.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

- Zetterling, Niklas; Tamelander, Michael (2009). Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany's Greatest Battleship. Drexel Hill, PA: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-04-0.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Iron Duke (ship, 1912). |