Hacienda Luisita

Hacienda Luisita is a 6,453-hectare sugar plantation located in the province of Tarlac, Philippines. The hacienda spans 11 barangays in three towns of Tarlac province. Most of the original farmworkers reside in 10 villages – Barangays Balete, Cutcut (or Sta. Catalina), Lourdes (formerly Texas), Mapalacsiao (formerly Luisita), Asturias, and Bantog in Tarlac City; Barangay Motrico in La Paz town; and Barangays Parang (formerly San Sebastian), Mabilog (formerly Pasajes) and Pando in Concepcion town. The original estate includes the Central Azucarera de Tarlac (CAT) sugar mill and a golf course. The eleventh village is Barangay Central in Tarlac City which houses the CAT sugar mill, the St. Martin de Porres Hospital and the Our Lady of Lourdes Church. It features Luisita Golf and Country Club, a golf course and Las Haciendas de Luisita Subdivision, a 5-interconnected luxury subdivision.[1]

| Hacienda Luisita | |

|---|---|

Hacienda Luisita main road, from Barangay San Miguel, Tarlac to Balite, Lourdes, Central and Mapalacsiao, Tarlac City | |

| Town/City | Tarlac City, La Paz, and Concepcion |

| Province | Tarlac |

| Country | Philippines |

| Coordinates | 15°26′N 120°39′E |

| Owner | Hacienda Luisita, Inc. |

| Area | 6,453 ha (15,950 acres) |

| Produces | Sugar |

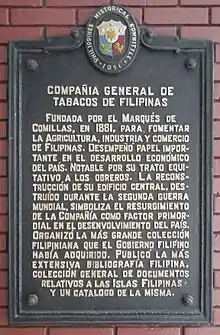

Originally owned by the Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas, it is now owned by the Cojuangco family who acquired the hacienda in the late 1950s. The estate's incorporators, who control 70 percent of Hacienda Luisita's stock shares, are Pedro Cojuangco, Josephine C. Reyes's heirs, Teresita C. Lopa's heirs, José Cojuangco, Jr., and María Paz C. Teopaco, all siblings of the late former President Corazón C. Aquino who, on the day she became President of the Philippines, bequeathed her shares to her children and the Daughters of Charity and other non-profit organizations. The remaining 30 percent of the stock shares was given to farm workers under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program's stock distribution option scheme.[2]

History

Spanish era

Hacienda Luisita was once part of the holdings of Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas, Sociedad Anónima, better known as Tabacalera. The land was owned by Spain, by virtue of the country's colonial relationship to the Philippines. The tobacco company was founded on 26 November 1881 by the Spaniard Antonio López y López from Comillas, Cantabria and Santiago de Cuba, and Don Guillermo Rubio born in Santander, Cantabria.[3]

In 1780, the popularity of cigars in the Philippines prompted Spanish authorities to impose a tobacco monopoly, such that the only ones able to plant, manufacture, and sell cigars were the colonial government. Tabacalera was a private enterprise Lopez y Lopez founded with the sole intention of taking over the Philippine tobacco monopoly from the Spanish colonial government; the monopoly was abolished a year after Lopez y Lopez acquired the estate. This included the Hacienda Antonio (named after his eldest son), Hacienda San Fernando and Hacienda Isabel (named after his eldest daughter) in Cagayán and Isabela provinces where the La Flor de Isabela cigar was cultivated.[4] Due to the high profits of sugar and tobacco in the Philippines, Antonio López y López and his son, Claudio López Bru, the second to hold the title, donated some of the profits to the Jesuits to create the Pontifical University of Comillas, a university outside Madrid.[5]

American period

During the American period, the hacienda supplied almost 20% of America's sugar from 1898 to the 1940s (from the Spanish–American War until World War II) back when the Tabacalera still owned it.[6] Because of this, the Luisita sugar became popular locally as well. The Spanish-owned hacienda flourished mainly because of America's obsession with sugar. In the 1920s, Tabacalera then left the tobacco business to focus on the growing sugar industry to cater to US’ needs since this product was more profitable at the time.[4] They invested heavily on the business by constructing a sugar refinery known as "Central Azcurarera de Tarlac" (CAT) which used America's centrifugal machinery technology in order to double the production and lessen the cost of shipping sugar to a refinery in Laguna owned by the Roxas Family.[6]

The refinery became the largest sugar central in the Philippines thus increasing Tabacalera's profits. With a new production line, the refinery required a new system for more efficiency. Workers were laid off or forced to retire since old farm workers were not familiar with the new technology. This then resulted to continuous protests for a year. The Hacienda produced 126,129 tons of sugar in 1928 as well as allegedly receiving additional tons of sugar with current prices of Php 23,450. The workers then found out that the hacienda was receiving multiple fines that were deducted from the workers’ wages, which sparked outrage.[6]

Japanese occupation of the Philippines

During the Japanese period, the Hacienda still continued all operations in sugar production. A Japanese policy was put in place to ensure that supplies in commodities such as rice and sugar were not interrupted and were made available to Filipinos in order to avoid insurgencies or rebellions. The continuation of the production both served the Japanese and the Spanish's interests at that time.[1]

In 1942, Luis Taruc and 200 members formed HUKBALAHAP, a peasant based guerrilla army to fight the Japanese forces. Many of these members were farmers of Hacienda Luisita because of their discontent with Tabacalera, advocating for the distribution of land. On 25 January 1945, General Douglas Macarthur set up his headquarters at Hacienda Luisista to fight Japanese forces in the Philippines.

In 1947, a farmer's wife was reported to be raped by one of the remaining Spanish directors of the hacienda. In support of her, other wives lay themselves on the railroad tracks to stop the trains carrying sugar from being delivered. The Spanish director immediately left for Spain which pushed the Huks to execute Spanish "encargados" or managers in front of the guest house when they refused to admit to the crime.[6]

José Cojuangco period (1957-1976)

In 1957, the owners of the Tabacalera decided to sell Hacienda Luisita as well as the sugar mill, Central Azcurarera de Tarlac (CAT), because of the HUKBALAHAP rebels who were causing them problems.[1] The CAT was supposed to be sold to the Lopez family of Iloilo but then the purchase was vetoed by President Ramon Magsaysay due to the clan owning multiple businesses such as Meralco, ABS-CBN, the Manila Chronicle, Negros Navigation, as well as a number of substantial agricultural holdings, which the president deemed to problematic because the Lopez's were becoming too powerful.[1] President Magsaysay then offered the Central Azcurarera de Tarlac to Jose Cojuangco Sr. through Ninoy Aquino Jr (Jose's son-in-law) in early 1957. Ninoy Aquino was Magsaysay's political prodigy and personal assistant at that time, which helped the Cojuangcos in purchasing the CAT.[6] As agreed upon, the hacienda would be paid for in pesos, while the CAT would be paid for in US dollars. The Philippine government aided the Cojuangcos in obtaining the loans needed to pay the price.[7]

In 1957, the clan took control of the CAT and the hacienda through Manufacturer's Trust Co New York. endorsed by the Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) as well as Government System Insurance Service (GSIS).[1] The BSP then approved the loan in August 1957 under two conditions, one of which states that the CAT be bought together with Hacienda Luisita and that the hacienda shall be distributed to farmers under the Magsaysay's social justice program.[7][8] The government then authorized a P 5.9 million loan from GSIS which was approved in November 1957. The Cojuangcos were given a ten-year window to distribute the lands to farmers as stipulated.[1] Finally on 1958, Jose Cojuangco Sr.’s Tarlac Development Corporation (TADECO) became the new owner of Hacienda Luisita as well as the CAT. Ninoy Aquino then became Luisita’s first administrator.[6]

Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos (1965-1986)

The year 1967 marked the end of the 10-year window given to the Cojuangcos that the Philippine government gave in order to distribute the land. However, the Cojuangcos failed to distribute any land. In response, farmers’ organizations began to form in order to push for the distribution.This was combined with political unrest in the nation. The United Luisita Workers Union (ULWU) was created because of this. This year was also when Benigno Aquino Jr. was elected senator.[9][10]

Nationwide Martial Law was declared on 21 September 1972, and Benigno Aquino Jr., the son-in-law of Jose "Pepe" Cojuangco, was among the first to be imprisoned for treason, murder, subversion and weapons possession.[11] During this time, the Marcos administration took an interest in enforcing land reform.[12]

Jose Cojuangco died on 21 August 1976, five years from the day of the Plaza Miranda bombing. On 7 May 1980, the government filed a case against Tarlac Development Corporation, or TADECO (a Cojuangco company) before the Manila Regional Trial Court (RTC). The case (Republic of the Philippines vs. TADECO, Civil Case No. 131654, Manila Regional Trial Court, Branch XLIII) sought the surrender of the hacienda to the Ministry of Agrarian Reform in order to properly distribute the land to the qualified farm workers. The Cojuangcos responded to the case saying that there were no such tenants or farm workers qualified to receive such land.[7] This was during the same time that Ninoy Aquino and his family were to leave for exile in the United States. At the time, the anti-Marcos block portrayed this lawsuit as an attack on the Aquino family by the Marcoses, while the farmers viewed it as the government taking action to help them.[10]

Ninoy Aquino was shot on 21 August 1983, as he was descending the plane. On 2 December 1985, the Manila RTC ordered TADECO to surrender Hacienda Luisita to the Ministry of Agrarian Reform (MAR, now the Department of Agrarian Reform, or DAR) due to noncompliance of the land reform act. TADECO alleged that the hacienda housed no tenants, and that the hacienda's sugar lands are not covered by existing agrarian reform legislations. The Cojuangcos brought the case to the Court of Appeals due to their belief that the case was an act of harassment by the Marcos administration because Corazon Aquino took her late husband's place to run against Marcos in the 1986 snap elections. Of note is that land reform was one of the issues her campaign focused on. The snap elections were fraught with anti-Marcos allegations, and led to the People Power Revolution.[7][13][14]

Presidency of Corazón “Cory” C. Aquino (1986-1992)

Despite the installation of Corazon Aquino as president, the farmland was not being distributed. Thousands of farmers marched to Malacañang Palace on 22 January 1987. 13 protesting farmers were shot in what is now known as the "Mendiola Massacre." On 22 July 1987, Aquino issues Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229, which outlines her agrarian reform program. On 18 May 1988, the case the Marcos administration filed against TADECO was dismissed by the Court of Appeals, and the Philippine government, under the Aquino administration, moved to dismiss its own case. On 10 June 1988, the Republic Act No. 6657 (Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law) is signed into law by President Aquino. The law includes a Stock Distribution Option (SDO) which would allow landowners to distribute the stock shares of the land to the farmers, instead of actual land.[15]

In compliance with the CARP, 4915.75 hectares of Hacienda Luisita were folded into Hacienda Luisita Inc. (HLI) on 23 August 1988, in order to comply with a stock distribution agreement between the landowners and farm workers. The hacienda's farmers voted 92.9% in favor of the SDO route with regards to the land reform act. This agreement was implemented on 11 May 1989. The farm workers' therefore now owned 33% of the plantation, while the Cojuangcos retained ownership of the remaining 67% of stocks. In accordance with the SDO agreement, there would be a 30-year schedule for distributing and transferring the stocks to the farmers.[13]

Present period (1992-onwards)

On 1 September 1995, 3,290 hectares of the hacienda was reclassified from agricultural to commercial, industrial, and residential land. This was passed by the Provincial Board of Tarlac, the governor of which was Margarita "Tingting" Cojuangco, wife of Jose "Peping" Cojuangco, Jr., brother of Cory Aquino. The Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) approved the conversion of 500 hectares in 1996.[13]

In 2003, hacienda workers filed a petition to have the SDO agreement revoked, and in 2005, the DAR cancelled the stock distribution agreement. It was cited that the SDO had failed to improve the lives of the more than 5,000 farmer beneficiaries. HLI appealed this decision, but in May 2006, the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council rejected with finality the motion of HLI to reconsider the revocation of the stock distribution agreement.[16] However, the Supreme Court issued a temporary restraining order, stopping the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council from parceling out the land to the workers.[17][18]

Criticisms of ownership

The Cojuangcos have often garnered criticism for their ownership of the estate with some critics comparing the situation to problems seen in oligarchy based systems.[19] The estate's incorporators, who control 70 percent of the stock shares of the Hacienda, are Pedro Cojuangco, the children of Josephine C. Reyes, the heirs of Teresita C. Lopa, José Cojuangco, Jr., and María Paz C. Teopaco—all of whom were siblings of the late former President Corazón C. Aquino who, on the day she became President of the Philippines, bequeathed her shares to her children and non-profit organizations such as the Daughters of Charity for fear that it would be used as political propaganda.[20] The remaining 30 percent of the stock shares was given to farm workers under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program's Stock Distribution Option scheme.[17]

Current Issues and Problems

Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP)

The signing into law of Republic Act No. 6657 or the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law (CARL) on 10 June 1988 signaled the beginning of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) under former President Corazon Aquino. One of the clauses of the CARP provided for a Stock Distribution Option (SDO), which would allow for compliance with the agrarian reform law by distributing stocks of the hacienda to the farm workers rather than actual land.[21]

On 9 May 1989, a referendum was held among the farm workers of Hacienda Luisita to determine whether stocks or land would be the means by which the hacienda would be distributed. The results of the May 1989 referendum, as well as a second referendum held in October of the same year, found that a great majority of the Hacienda farm workers voted in favor of distribution of stock rather than land.[13] The terms of the SDO agreement of the Hacienda are quoted as follows:

“At the end of each fiscal year, for a period of 30 years, the SECOND PARTY (HLI) shall arrange with the FIRST PARTY (TADECO) the acquisition and distribution to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers) on the basis of number of days worked and at no cost to them of one-thirtieth (1/30) of 118,391,976.85 shares of the capital stock of the SECOND PARTY (HLI) that are presently owned and held by the FIRST PARTY (TADECO), until such time as the entire block of 118,391,976.85 shares shall have been completely acquired and distributed to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers)."[7]

The SDO agreement however was met with considerable criticism, most notably in 2003 when hacienda workers (farmers, HLI supervisory group workers, union officers) began filing petitions to the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) to have the SDO agreement revoked due to their dividends and other promised benefits not being given. Daily wage was at P194.50, and there was only one working day per week, due to the mechanizing of some tasks in the hacienda. A petition with more than 5,300 signatures was filed to revoke the SDO agreement and stop land conversion in the hacienda.

In 2004, the workers' union tried to negotiate with the management to increase daily wages to P225 and increase work days to 2–3 days weekly. Management refused. In 1 October of that year, 327 workers (farm workers and union officers) were retrenched.[13][22]

November 2004 Massacre

On 6 November 2004, United Luisita Workers Union (ULWU) and the Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor Union (CATLU) launched a strike near Gate 1 of the Central Azucarera de Tarlac sugar mill. The protesters were pushing for an increase in their P9.50 weekly wage, increased worker benefits and, more broadly, a greater commitment for national land reform.[23][24] Over a thousand farmers, and another several thousand union members attended the demonstration.

On 16 November 2004, ten days after the start of the said strike, police and soldiers were dispatched by then Labour Secretary Patricia Santo Tomás, to storm and disperse the blockade. The enforcers utilized tear gas, water cannons, guns, and military vehicles to disseminate the crowd. Seven of the people participating in the rally were killed, an estimated number of 121 people, adults and children, were injured, and 133 people were arrested and detained.[25]

The incident has sparked a national outcry, however, then Deputy Speaker Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III, Representative of Tarlac, claims that the dispersal done by the enforcers was justified. A case was filed against the police and military with regards to the injuries and deaths, however it was dismissed by the office of the Ombudsman in 2010. Proceeding that, a motion to reopen the case was filed by the families of the victims, however, it was declined by the Office of the Ombudsman on 2 October 2014.

The November 2004 massacre or more popularly known as the Hacienda Luisita massacre is one of the most prominent instances of protest related deaths of Filipinos in recent years.[26] In the months following the Hacienda Luisita massacre, eight more people who either supported or provided evidence to the farmers’ cause were found murdered, beginning with the assassination of peasant leader Marcelino Beltran just before he was to testify about the massacre.[27]

Revocation of the Stock Distribution Option Agreement

In the aftermath of the November 2004 massacre, the DAR established Task Force Luisita to conduct further investigations and conduct focus group discussions among the farmers. On 22 September 2005, based on the findings of its investigations, Task Force Luisita recommended the revocation of the SDO agreement forged between Hacienda Luisita Inc. (HLI) and the farm workers.[13] Three months later, on December of the same year, the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC) issued a resolution ordering the revocation of the SDO agreement and the distribution of the hacienda's land among the farm workers. Land distribution and the cancellation of the SDO agreement was halted however in June 2006 when the Supreme Court granted the petition of HLI and issued a temporary restraining order on the PARC resolution.[17]

On 18 August 2010, oral arguments on the Hacienda Luisita case were heard by the Supreme Court for the first time since the dispute was brought to its doors in 2006. A landmark decision was ultimately reached on 5 July 2011, wherein the Supreme Court lifted the temporary restraining order on the 2005 PARC resolution and upheld both the distribution of land to the hacienda's farm workers and the revocation of the SDO agreement forged in 1989.[7][13] In acknowledgement of the fact that 93% of the hacienda's farm workers voted in favor of SDO in the 1989 referendum, included in the July 2011 decision was the further mandating of the DAR to hold another referendum to determine which among the hacienda's farm workers would wish to receive land or to remain as stockholders of HLI. This decision to hold another referendum was met with considerable criticism however as critics asserted that agrarian reform laws stipulate that land distribution should be the only viable option and alternatives such as the SDO violate this.[28]

On 22 November 2011, the Supreme Court modified its July 2011 decision and revoked the option for the hacienda farm workers to remain as stockholders of HLI, stating:

“Upon a review of the facts and circumstances, We realize that the FWBs [Farmer-Worker Beneficiaries] will never have control over these agricultural lands for as long as they remain as stockholders of HLI…

In line with Our finding that control over agricultural lands must always be in the hands of the farmers, We reconsider our ruling that the qualified FWBs should be given an option to remain as stockholders of HLI, inasmuch as these qualified FWBs will never gain control given the present proportion of shareholdings in HLI.”[29]

Disputes over Landowner Compensation

In compliance with agrarian reform laws, the Supreme Court decisions further stated that HLI was entitled to payment by the government as just compensation for distributing the hacienda's lands to the farm workers.[7][29] The corporation was to receive compensation for the distributed land based on its valuation on the date of its taking from HLI.

In line with this, HLI presented 2 January 2006 as the appropriate date of taking based on when a Notice of Coverage was issued by the DAR placing the hacienda's land under compulsory acquisition. However the Supreme Court maintained its initial stance that the date of taking be marked at 21 November 1989, based on when the original stock distribution plan was approved, stating this was when ownership of the lands was initially relinquished to make way for its distribution to the farm workers via stock.[30] Under the 2006 valuation of the distributed land, the compensation payment would have amounted to about P5 billion while under the 1989 valuation of the distributed land, the compensation would total only about P200 million.[31]

April 2012 Supreme Court Ruling

On 24 April 2012, the Supreme Court released a final and executory decision regarding Hacienda Luisita:

"To recapitulate, the Court voted on the following issues in this manner:

1. In determining the date of taking, the Court voted 8-6 to maintain the ruling fixing November 21, 1989 as the date of taking, the value of the affected lands to be determined by the LBP and the DAR;

2. On the propriety of the revocation of the option of the FWBs [Farmer-Worker Beneficiaries] to remain as HLI stockholders, the Court, by unanimous vote, agreed to reiterate its ruling in its November 22, 2011 Resolution that the [stock distribution option] granted to the FWBs stays revoked;

3. On the propriety of returning to the FWBs the proceeds of the sale of the 500-hectare converted land and of the 80.51-hectare SCTEX land, the Court unanimously voted to maintain its ruling to order the payment of the proceeds of the sale of the said land to the FWBs less the 3% share, taxes and expenses specified in the fallo of the November 22, 2011 Resolution;

4. On the payment of just compensation for the homelots to HLI, the Court, by unanimous vote, resolved to amend its July 5, 2011 Decision and November 22, 2011 Resolution by ordering the government, through the DAR, to pay to HLI the just compensation for the homelots thus distributed to the FWBS.

WHEREFORE, the Motion to Clarify and Reconsider Resolution of November 22, 2011 dated December 16, 2011 filed by petitioner Hacienda Luisita, Inc. and the Motion for Reconsideration/Clarification dated December 9, 2011 filed by private respondents Noel Mallari, Julio Suniga, Supervisory Group of Hacienda Luisita, Inc. and Windsor Andaya are hereby DENIED with this qualification: the July 5, 2011 Decision, as modified by the November 22, 2011 Resolution, is FURTHER MODIFIED in that the government, through DAR, is ordered to pay Hacienda Luisita, Inc. the just compensation for the 240-square meter homelots distributed to the FWBs.

The July 5, 2011 Decision, as modified by the November 22, 2011 Resolution and further modified by this Resolution is declared FINAL and EXECUTORY. The entry of judgment of said decision shall be made upon the time of the promulgation of this Resolution.

No further pleadings shall be entertained in this case.

SO ORDERED."[30]

Current status

The Supreme Court ruling states that the 4,916 hectares of Hacienda Luisita is to be redistributed to 6,296 registered farm-worker beneficiaries, while the Hacienda Luisita Incorporated (HLI) will be receiving 40,000 pesos per hectare as compensation.[31] This is based on the 1989 valuation of the Hacienda Luisita that the Supreme Court had voted upon.[32] But from the 4,916 hectares to be redistributed, 500 hectares were converted into non-agricultural use on 18 August 1996 by the Department of Agrarian Reform, while 80.5 hectares was also subtracted for the development of the Subic Clark Tarlac Expressway (SCTEX).[33] Other inconsistencies within area size have caused conflicting numbers, but according to the DAR this then leaves only 4,099.92 hectares of land to be distributed.[1]

The process of land distribution was decided to be through lottery system, wherein the names of the beneficiaries are placed into a drum, and those chosen will be given the Lot Allocation Certificate (LAC).[34] Farmer-worker Beneficiaries then sign the Application to Purchase and Farmers' Undertaking (APFU), for the registry of their Certificate of Land Ownership Award (CLOA), which is the actual land title. The lottery system had started on 18 July 2013 in Barangay Cutcut, Tarlac City with 340 farmers being given the first batch of Lot Allocation Certificates.[34] But it was on 30 September 2013, where DAR Secretary Virgilio de los Reyes started awarding the actual Certificate of Land Ownership (CLOA) to 600 Farmer-worker beneficiaries in Barangay Pando.[35]

As of 12 July 2016, 4,099 hectares have been already distributed to farmers, but the sales shares from the Hacienda Luisita's converted land to be paid to the farmer-worker beneficiaries have been left unpaid which amounts to 1.3 billion pesos.[36] On 24 April 2017, protesters consisting of the Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (UMA) and other militant organizations had gone to Hacienda Luisita to protest against the 348 hectare land that was turned over to Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (RCBC) back on 25 November 2004 for a 431.7 million peso loan obligation.[37] The protest led to property damage, where protesters had destroyed over 100 meters of a wall surrounding the contested lot. On 21 February 2018, Luisita Land Corporation has since filed a case against 15 farmers for the protest, for malicious mischief and trespassing of the RCBC owned land.[38]

As of 4 July 2018, the Hacienda Luisita has fully complied with distributing the sales shares to farmers.[39] The 1.3 billion peso was broken down as such: P500 million received from Luisita Realty Inc. for a 200 hectare lot sold in 1996, P750 million for the selling of Luisita Industrial Park, and around P80 million for the 80.51 hectares used for the SCTEX road network.[40] The ruling also states that 3% of the earlier stock transfers that were paid to the farmers will be deducted from the 1.3 billion to be received.

See also

References

- Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (UMA) (November 2013). "For Land and Justice: The Continuing Agrarian Struggle in Hacienda Luisita. Report of the 2013 Hacienda Luisita National Fact-Finding Mission" (PDF). Luisita Watch. UMA Pilipinas. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Cervantes, Ding (4 January 2016). "DAR set to raffle off Hacienda Luisita land". Philstar Global. The Philippine Star. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "Our History". Tabacalera. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Sison, Norman (5 December 2011). "Tabacalera: 130 years of cigars and Philippine history". Philstar Global. The Philippine Star. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY". comillas.edu. Comillas Pontifical University. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- McMurray, Marisse Reyes (1996). Tide of Time. Makati City, Philippines: Jose Cojuangco and Sons, Inc. pp. 263–309. ISBN 978-9719161004.

- "G.R. No. 171101. July 5, 2011". sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Supreme Court of the Philippines. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Hacienda Luisita Timeline". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Dychiu, Stephanie (22 November 2009). "Ghosts of Hacienda Luisita back to haunt Noynoy candidacy". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Dychiu, Stephanie (10 January 2010). "Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Benigno Aquino Jr". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Kerkvliet, Benedict (1974). "Land Reform in the Philippines Since the Marcos Coup". Pacific Affairs. 47 (3): 286–304. doi:10.2307/2755767. JSTOR 2755767.

- "Holding on: A Hacienda Luisita timeline from the Spanish to the Noynoy eras". GMA News Online. GMA. 18 August 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Elections of 1986". Malacañan Palace: Presidential Museum and Library. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 229 July 22, 1987". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Landlordism in the Philippines: Hacienda Luisita as large as Makati and Pasig Cities combined". la.indymedia.org. Los Angeles Independent Media Center. 13 September 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- Calonzo, Andreo (12 September 2009). "Sen. Noynoy eyes giving up family rights over Luisita". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "Hacienda Luisita". fian.org. FIAN International. 28 November 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Doronila, Amando (14 September 2009). "Aquino meets estate issue head-on". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009

- Tanola, Nadezhda (13 September 2009). "Solve Hacienda Luisita massacre first, Noynoy urged". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- Makabenta, Yen (30 May 2014). "Arroyo's and Corona's ordeal: It was always about Hacienda Luisita". manilatimes.net. The Manila Times. Retrieved 9 July 2018..

- Pastrana, Dante (7 May 2010). "Hacienda Luisita haunts Philippine presidential candidate Aquino". World Socialist Web Site. International Committee of the Fourth International. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Cepeda, Cody (15 July 2016). "Within confines: A farmer's life in Hacienda Luisita". thelasallian.com. The LaSallian. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Simbol, Dax (16 November 2016). "12 years on, still no justice for Hacienda Luisita massacre victims". Rappler.com. Rappler. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Dychiu, Stephanie (26 January 2010). "How a workers' strike became the Luisita Massacre". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Over a Dozen Hacienda Luisita Strikers and Their Children Killed". internationalist.org. Internationalist Group. December 2004. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Dychiu, Stephanie (11 February 2010). "After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Dedace, Sophia (5 July 2011). "Stocks or land? SC calls for new Luisita referendum". GMA News Online. GMA. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "G.R. No. 171101. November 22, 2011". sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Supreme Court of the Philippines. 22 November 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "G.R. No. 171101. April 24, 2012". sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Supreme Court of the Philippines. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Pedrasa, Ira (3 May 2012). "SC releases final ruling on Hacienda Luisita". ABS-CBN News. ABS-CBN Corporation. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- de Santos, Jonathan (24 April 2012). "SC votes for 1989 rates valuation of Luisita land". Yahoo! News. Yahoo!. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Ranada, Pia (24 April 2014). "Two years on, Luisita land distribution a failure – farmers". Rappler.com. Rappler. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Gutierrez, Natashya (18 July 2013). "Hacienda Luisita land distribution begins". Rappler.com. Rappler. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Cruz, Efren S. (3 October 2013). "Hacienda Luisita and agrarian reform". Philstar Global. The Philippine Star. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Mia, Ian Benedict (12 July 2016). "28 years of agrarian reform in Hacienda Luisita". thelasallian.com. The LaSallian. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Simbol, Dax (24 April 2017). "Farmers break Hacienda Luisita walls". Rappler.com. Rappler. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Orejas, Tonette (21 February 2018). "Luisita firm sues farmers for breaking into bank lot". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Hacienda Luisita done distributing sale shares to farmers – SC". Rappler.com. Rappler. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Pedrasa, Ira (23 November 2011). "SC orders distribution of Hacienda Luisita". ABS-CBN News. ABS-CBN. Retrieved 18 July 2018.