Hamburg Observatory

Hamburg Observatory (German: Hamburger Sternwarte) is an astronomical observatory located in the Bergedorf borough of the city of Hamburg in northern Germany. It is owned and operated by the University of Hamburg, Germany since 1968, although it was founded in 1825 by the City of Hamburg and moved to its present location in 1912. It has operated telescopes at Bergedorf, at two previous locations in Hamburg, at other observatories around the world, and it has also supported space missions.

| |

| Organization | University of Hamburg |

|---|---|

| Observatory code | 029 |

| Location | Bergedorf, Hamburg, Germany |

| Coordinates | 53.480°N 10.241°E |

| Established | 1909 (1802) |

| Website | www |

Location of Hamburg-Bergedorf Observatory | |

The largest near-Earth object was discovered at this Observatory by German astronomer Walter Baade at the Bergedorf Observatory in Hamburg on 23 October 1924.[1][2] That asteroid, 1036 Ganymed is about 20 miles (35 km) in diameter.[3]

The Hamburg 1-meter reflector telescope (first light 1911) was one of the biggest telescopes in Europe at that time, and by some measures the fourth largest in the World.[4][5] The Observatory also has an old style Great Refractor (a Großen Refraktor), a long telescope with a lens (60 cm/~23.6 in aperture) with a tube focal length of 9 meters (~10 yards), and there is also a smaller one from the 19th century that has survived.[4] Another historical item of significance is the first and original Schmidt telescope, a type noted for its wide-field views.[4]

Among its achievements, the director of the Observatory won the 1854 Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society for a 1852 star catalog.[6]

History

Stintfang (1802–1811)

The precursor of Hamburg Observatory was a quasi-private observatory by Johann Georg Repsold built in 1802, originally located at the Stintfang in Hamburg.[7] It was built in the city with permission of the Congress.[6] It started in 1803, and had a meridian circle built by Repsold .[8][6] However, it was destroyed in 1811 by a war. Repsold, Reinke, and J.C. von Hess submitted a proposal to Hamburg for city observatory that same year, to rebuild.

Millerntor (1825–1906)

Funding for a new Observatory was approved in August 1821, on the condition J. G. Repsold built the instruments. The new observatory was completed in 1825 next to the Millerntor. However, in 1830 Repsold died while fighting a fire (he was also a Hamburg fireman) and the City of Hamburg voted to take over and continue running the observatory in 1833.[9] First director became Charles Rümker who had accompanied Thomas Brisbane to build the first Australian observatory at Parramatta.[10] Christian August Friedrich Peters became assistant director in 1834. In 1856 Rümker's son George became director of the observatory.

In 1854 Carl Rumaker won the Gold Medal from the Royal Society for year, for his 1852 Star catalog, which had the positions of 12000 stars.[6]

In 1876 funding was received for 'The Equatorial', a 27 cm (11 in) refractor; it was later moved to Bergedorf.

After the move to Bergedorf, the site was partially demolished and rebuilt into the Museum of Hamburg History (Hamburgmuseum / Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte).

Bergedorf (1912–present)

Because of the increasing light pollution, in 1906 it was decided to move the observatory to Bergedorf. In 1909 the first instruments were moved there, and in 1912 the new observatory was officially dedicated.

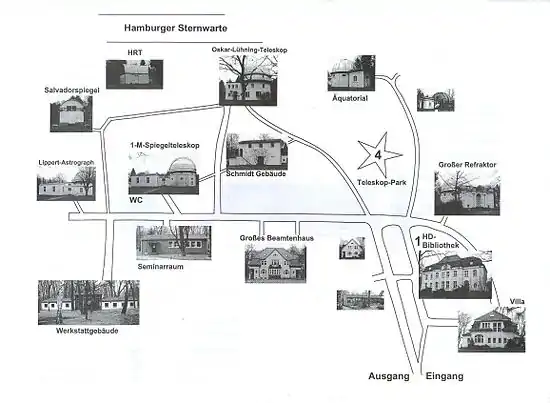

One of the overall design elements of Bergeforf, is that each instrument was placed in its own building, rather than integrated in one large building.[11]

Two new instruments for the Bergedorf location were the 60 cm (~23.6 inch) aperture Great Refractor by Reposold, and Meridian Circle.[12] One unique feature of Hamburg Great Refractor is an Iris control that allows the aperture to be adjusted from 5 to 60 cm.[13] Two lens were produced by Steinheil, one for photography and another for visual observing, both delivered in the early 1910s.[13]

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) was founded at Bergedorf in 1962. That organization put a lot telescopes in the southern hemisphere, which is not as viewable from northern part of Earth.

The Hamburg 1 m Reflector (39″/100 cm objective aperture) was the world's fourth largest reflector when it began operations in 1911.[14] Catalogs include the AGK3-Sternkatalog (completed over 1956-1964)

In 1968 the observatory became part of Hamburg University.[15] In 1979 a small museum to Bernard Schmidt was inaugurated.[8] In 2012, 100 years at Bergedorf was celebrated.[16]

In 2019, the Great Refractor building was re-open in June after it was modernized.[17]

1-meter reflector

The 1 meter reflector at Hamburg Observatory was the largest by aperture in Germany, and one of the largest in Europe, and was also among the largest telescopes of any type in the World at that time.

- Largest telescopes (all types) in 1911)

Note that the prevailing glass mirror technology at this time was silver coated glass, not vapor deposited aluminum which did not debut until several decades later. Speculum metal mirror reflected something like 2/3 of the light, and the lens telescopes were popular for their virtues but had enormous and expensive domes due to their long focal length (also they had issue with chromatic aberration that were solved in a different way by reflecting designs)

Telescopes

- Telescopes [26]

- The Great Refractor, a great refractor telescope with an objective diameter (60 cm) and focal length (9 m). By Repsold, and with optics from Steinheil. (The observatory's Großen Refraktor)

- The Equatorial, a refractor with aperture of 26 cm and focal length. Built in the 1870s and moved to Bergedorf.

- Salvador Mirror, a Cassegrain with 8 m focal length and 40 cm mirror.

- The Meridian Circle, a meridian circle built in 1907. (by A. Repsold & Söhne)

- Lippert Telescope, three astrographs refractors on one mount. Built by Carl Zeiss, funded by Eduard Lippert

- 1 Meter Reflector Telescope, activated in 1911. By Carl Zeiss. The largest telescope in Germany from 1911 to 1920

- Astrograph, with 8.5 cm objective, focal length 2.06 m. Built in 1924.[8]

- Schmidtspiegel, the first Schmidt telescope by Bernhard Schmidt. Now part of a Schmidt Museum

- Photographic refractor (Zonenastrograph), an instrument funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in 1973. 23 cm diameter aperture and 205.3 cm focal length. It was built by Carl Zeiss Oberkochen.

- Oskar-Lühning Telescope, s Ritchey-Chretien with 1.20 m aperture diameter and a focal length of 15.60m in the Cassegrain focus. Built in 1975 and refurbished as robotic telescope in 2001.

- A planned large Schmidt telescope was finished in 1954 and moved to Calar Alto Observatory in 1976, with the Oskar-Lühning taking over its spot in the Observatory.

- Hamburg Robotic Telescope (HRT) was built by Halfmann Teleskoptechnik. It was tested in 2002, and went online in 2005.

Offsite telescopes

- In 1968 a 38 cm reflector was set up by the Hamburg Observatory at Stephanion Observatory in Greece.[27]

- The aforementioned Schmidt was moved to Calar Alto Observatory in 1976. Some work was done with data from Effelsberg

- The HRT telescope has been installed in March 2013 in Guanajuato, Mexico at the LaLuz Observatory of the University of Guanajuato. It is now in successful operation under its new name TIGRE. The costs and observing time are shared according to a trilateral agreement between the Universities of Liege, Guanajuato and Hamburg, the latter still leading the effort.

People of Hamburg Observatory

Directors of the Observatory:

- Johann Georg Repsold (from 1802–1830)[28]

- Christian Karl Ludwig Rümker (director from 1833–1857) [29]

- George Rümker (director from 1857–1900)

- Richard Schorr (1900–1941)

- Otto Heckmann (1941–1968) [30] 1962 became 1st head of the newly formed European Southern Observatory

- Alfred Behr (1968–1979)

- Co-Director with Behr: Alfred Weigert (1969–1992)[31]

Bernhard Schmidt, inventor of the Schmidt camera worked at the Observatory including making telescopes, instruments, and observations starting in 1916. Walter Baade successfully petitioned the Hamburg senate to have Schmidt camera installed in 1937, and it was completed in 1954 after work restarted on in 1951 after being interrupted by WWII. Walter Baade also succeeded in having a Schmidt camera built at Palomar Observatory in California.[32]

In 1928, Kasimir Graff made many observations at Hamburg until he left for the Vienna Observatory.

In 2009, South African pop star, singer and composer Ike Moriz filmed a music video called 'Starry Night'[33] both inside and outside the observatory buildings.[34] It features the Equatorial refractor telescope as well as the library and garden areas.[35] He also sang at the 100th anniversary exhibition 'Vision Sternwarte'.[36]

Association

Due to the difficult economic situation of the observatory, the "Förderverein Hamburger Sternwarte e.V." was founded in 1998.[37] The goals of the association are primarily to preserve the buildings and astronomical equipment of the observatory in accordance with the preservation order. In addition, it does public relations work and aims to open up parts of the site to the public in the future. The application for a World Heritage Site, which has been running since 2012, is an important focus of their work.

References

- "1036 Ganymed (1924 TD)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(1036) Ganymed". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 89. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_1037. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- Browne, Malcolm W. (25 April 1996). "Mathematicians Say Asteroid May Hit Earth in a Million Years". Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Telescopes and photographic plates". Hamburg University – Hamburg Observatory. 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Journal for the History of Astronomy. Science History PUblications. 2005.

- Anderson, S. R.; Engels, D. (April 2004). "A short history of Hamburg Observatory". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 114: 78–87. Bibcode:2004JBAA..114...78A. ISSN 0007-0297.

- J.G. Repsold, the founder of Hamburg observatory (in German)

- "A short history of the Hamburg Observatory—Principal Instruments of Hamburg Observatory". Uni-Hamburg. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Charles Rümker, Erster Sternwartendirektor in Hamburg (in German)

- Lockyer, Sir Norman (1911). Nature. Macmillan Journals Limited.

- "A SHORT HISTORY OF HAMBURG OBSERVATORY". www.hs.uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "The Hamburg Observatory" (PDF).

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 100 100 Years of the Observatory Bergedorf

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo - Hamburg, Germany. 19th June, 2019. The Great Refractor building was reopened on 19.06.2019 after a phase of modernisation. The observatory has one of the largest telescopes in". Alamy. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "New York Times "NEW HARVARD TELESCOPE.; Sixty-Inch Reflector, Biggest in the World, Being Set Up. "April 6, 1905, Thursday", Page 9". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Largest optical telescopes of the world". stjarnhimlen.se. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mt. Hamilton Telescopes: CrossleyTelescope". www.ucolick.org. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Tobin, William (1987). "Foucault's invention of the silvered-glass reflecting telescope and the history of his 80-cm reflector at the observatoire de Marseille". Vistas in Astronomy. 30 (2): 153–184. Bibcode:1987VA.....30..153T. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(87)90015-8. ISSN 0083-6656.

- Gascoigne, S. C. B. (June 1996). "The Great Melbourne Telescope and other 19th-century Reflectors". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 37: 101. Bibcode:1996QJRAS..37..101G. ISSN 0035-8738.

- "1914Obs....37..245H Page 248". Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Roger Hutchins (2008). British University Observatories, 1772-1939. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-7546-3250-4.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Stephanion Observatory, homepage

- "Hamburg Observatory". www.physik.uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A020359b.htm

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Otto Heckmann

- "Nachrufe : Alfred Weigert". Mitteilungen der Astronomischen Gesellschaft Hamburg. 76: 11. 1993. Bibcode:1993MitAG..76...11.. ISSN 0374-1958.

- Donald E. Osterbrock; Walter Baade (2001). Walter Baade: A Life in Astrophysics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04936-X.

- "Starry Night". YouTube.

- "Ike Moriz". Discogs. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- "Bergedorfs Stern in Südafrika". www.bergedorfer-zeitung.de (in German). 16 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Hamburg, Hamburger Abendblatt- (13 August 2011). "In die Sterne schauen, Gedichten lauschen und Musik genießen". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Förderverein Hamburger Sternwarte".

Bibliography

- Die Hamburger Sternwarte. ("The Hamburg Observatory"), Report on the Hamburg Observatory by R. Schorr, English Translation by Hamburg Observatory

- Einleitung zum Jahresbericht der Sternwarte Bergedorf für das Jahr 1906 ("The annual report for the Bergedorf Observatory for 1906), English Translation by Hamburg Observatory

- Agnes Seemann: Die Hamburger Sternwarte in Bergedorf. In: Lichtwark-Heft Nr. 73. Verlag HB-Werbung, Hamburg-Bergedorf, 2008. ISSN 1862-3549.

- Jochen Schramm: Die Bergedorfer Sternwarte im Dritten Reich. In: Lichtwark-Heft Nr. 58. Hrsg. Lichtwark-Ausschuß, Hamburg-Bergedorf, 1993.

- J. Schramm, Sterne über Hamburg - Die Geschichte der Astronomie in Hamburg, 2. überarbeite und erweiterte Auflage, Kultur- & Geschichtskontor, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-9811271-8-8