Hannah Cullwick

Hannah Cullwick (26 May 1833 – 9 July 1909) was a diarist who revealed less-known aspects of the relations between Victorian servants and their masters.

Working in domestic service, she caught the attention of Arthur Munby, a prominent barrister and philanthropist, who was making a close study of the conditions of working women.

To escape poverty, she married him reluctantly and secretly in 1873, but it was an unconventional partnership, with role-playing, as documented in both their diaries, which have survived, along with letters and photographs.

Early life

Cullwick was born on 26 May 1833 and raised in Shifnal, Shropshire, England. Her surname is pronounced as Cullwick, not Cullick. She came from solid Salopian yeoman stock, not the working-class origins sometimes claimed. Her father was Charles Fox Cullwick (1803–1847), a Master Saddler of Shifnal and a Burgess (Parliamentary voter) of Bridgnorth. The Cullwicks had been voters in Bridgnorth since 1630, usually voting in the Whitmore interest. The family had been Master Saddlers in Shropshire since one of Charles's great-great-grandfathers, Richard Cullwick (1648–c1720), of Newport, set up his saddlery business, about 1670.

Hannah's mother was Martha Owen (1800–1847), who had been a Lady's Maid to the aristocratic Mrs Eyton, the wife of the Rev. John Eyton, Rector of Wellington, Salop. Martha's elder brother was Richard Owen (1791–1864), a schoolmaster in Shifnal, who was also parish clerk. Martha's two sisters—Sarah Smallman (1805 – after 1881) and Eleanor Morris (1803–1863)—were both married to farmers, Charles Skelton Smallman (1799–1877) and John Morris (1796–1885), of The Firs, Flashbrook, Adbaston.

Hannah Cullwick had more than a dozen uncles and aunts and more than fifty first cousins. All of them were literate; and most of them were in business, as farmers, publicans, and saddlers.

Charles, Hannah's father, appears to have suffered business losses; the family were subsequently very poor. There were five children: James (1830–1915), Hannah, Dick (1836–1887), Ellen (1839–1919), and Polly (1844–1924). James was a master wheelwright and later owned houses. Dick was a master saddler and became a harness maker in London. Ellen married William Cook, the Registrar for Poplar in London. Polly owned a large haberdashery store in the Ipswich Buttermarket.

The five children received a rudimentary schooling. Hannah was sent for a couple of [two?] years to the Bluecoat Charity school in Shifnal. Money was so short that Hannah had to contribute to the family purse from the age of eight—first in the home of a solicitor's wife, Mrs Andrew Phillips, a friend and neighbour of the Cullwicks, and then in the inn next door [to the Phillips house or the Cullwick house?] before embarking on her long career in service.

Nursemaid

When she was fourteen, Hannah Cullwick became sole nursemaid to the large family of the Rev Robert Eyton (son of the Rev John Eyton) at Ryton Rectory. In that year, her mother, aged 47, died suddenly of an infection, and Hannah's employer in the Eyton household refused to let her travel the three miles to visit her family, for fear that the fever would spread to Ryton. A fortnight later, Hannah's father died, aged 44, leaving the five children (aged 16 down to 3) as orphans. James was in a wheelwright apprenticeship with Richard Pointon, in Shifnal, and Hannah was in service at Ryton Rectory. The three youngest children needed to be housed: Dick was placed in a saddlery apprenticeship in Horsely Fields, Wolverhampton, with his uncle, William Cullwick (1781–1853); Ellen lived with Aunt Small (née Sarah Owen) on her large farm, in Westbury, near Albrighton; and Polly went to live with her spinster aunt Elizabeth Cullwick (1789–1866), in Haughton, Shifnal.

When Hannah Cullwick was seventeen, she worked as under-housemaid for Lady Boughey at Aqualate Hall, Forton. She was dismissed after eight months because her mistress saw her (as she later recorded) "playing as we was cleaning our kettles".

Cullwick then worked for Lady Louisa Cotes (1814–1887), wife of John Cotes (1799–1874), of Woodcote, Sherriffhales. Louisa Harriet Cotes was the daughter of Charles Cecil Cope Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool, and half brother of Robert Banks Jenkinson, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool, who was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827. Lady Cotes took Cullwick to London.

Meeting with Arthur Munby

There, in 1854, Cullwick met Arthur Munby during one of his regular urban expeditions to investigate working women. Munby was struck by her size (5 feet and 7½ inches (171.45 cm), 161 pounds (73 kg)) and strength, combined with the nobility of character he claimed to see in working women. Cullwick saw him as an idealised gentleman, who celebrated the intense labour she did as a maid of all work. To be near Munby, she began to work in various middle-class households in London, including an upholsterer's, a beer merchant's, and that of a widow with several daughters, and in lodging houses (which gave her more freedom from supervision). She and Munby formed a lasting relationship, which led to a secret marriage in 1873.

Before she met Munby, Cullwick saw a lavish musical, The Death of Sardanapalus; it was the first time she attended the theatre in her life. The musical, based on the play by Lord Byron, told of an ancient, pacifist king who loved one of his slave girls. The slave, Myrrha, loved the king, but also had her own democratic and republican desires. Cullwick sympathised strongly with the play's heroine.

The relationship between Cullwick and Munby

Cullwick proudly called herself Munby's "drudge and slave", and called him "Massa", in a Master/slave relationship. For much of her life, she wore a leather strap around her right wrist and a locking chain around her neck, to which Munby had a key. She wrote letters almost daily to him, describing her long hours of work in great detail. She would arrange to visit him "in [her] dirt", showing the results of full day's cleaning and other domestic work. She had a particular interest in boots, cleaning hundreds each year, sometimes by licking them. She once told Munby that she could tell where her "Massa" had been by how his boots tasted.

Despite her display of subservience and loyalty, Cullwick remained independent. She stood up for herself if she thought the terms of her relationship with Munby were being violated. It was reluctantly that she entered marriage with Munby, seeing it as dependency and boredom. Once they were married, she moved to his lodgings in Fig Tree Court, Inner Temple, central London, where she lived as his servant, though she sometimes played the role of his wife. She also retained her own surname and insisted that Munby continue to pay her wages, and she had her own monetary savings. She left him far more often than he left her, and in 1877 she returned to domestic service in Shropshire. Munby was a regular visitor from 1882 until her death.

Later life

Hannah lived in several places between 1880 and 1900. She lived in Wolverhampton with her only niece—Jim's daughter, Emily Griffiths Gibbs (1856–1920), née Cullwick. Then Hannah lived for some time in Bearley, near Stratford-on-Avon, with Emily's father-in-law, Charles Gibbs; Charles's elderly mother, Hannah Bonehill Gibbs; and her two bachelor sons. Then Hannah Cullwick moved to a cottage between Shifnal and Wellington, close to her brother, Jim.

Hannah moved in 1903 to a small rented cottage in Wyke Place, Shifnal, owned by Jim Cullwick. She remained active until shortly before her death. On 9 July 1909, she died, aged 76; the cause of death was recorded as "failure of heart action and senile decay". Her remains were buried in St Andrew's churchyard in Shifnal; her gravestone bears the words "she was for 36 years of pure and unbroken love the wedded wife of Arthur Munby of Clifton Holme in the Wapentake of Bulmer".

Munby died in January 1910, aged 81. He left an estate of £26,000. He bequeathed his books and 2 deed-boxes filled with correspondence, diaries, and photographs, to the British Museum. They were unable to accept this legacy, and provision was made for the items to be kept at Trinity College, Cambridge, and not opened until 1950. The daughter of Emily Gibbs (Hannah's niece) was Ada Perks (1882–1971), of Bankes Road, Small Heath, Birmingham. She asked to represent the Cullwick family at the opening of the boxes; her request was denied, the reason given that the opening was a private matter. Dr. Ann Munby (great-nephew of Arthur Munby) attended.

Diaries

Hannah Cullwick's diaries reveal that her erotic games with Munby often included infantilism and ageplay, with Cullwick carrying Munby in her arms and holding him on her lap.

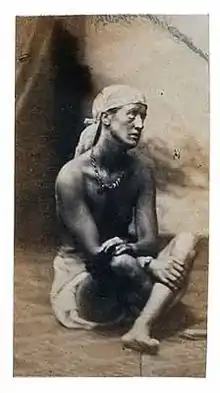

Cullwick appeared in Munby's photographs in many different roles: a farm girl, a kitchen drudge, a chimney sweep with blackface, a well dressed lady (though with her hands, unmistakably those of a working woman, prominently displayed), a Magdalen, and a man. Her ability to take different roles delighted Munby.

Cullwick's diaries (small, prejudicial selections of which are published as The Diaries of Hannah Cullwick, Victorian Maidservant in the controversial edition by the Marxist historian Lizbeth Stanley, not approved by Cullwick's family) provide detailed information on the lives of working-class Victorian servant women. They are a record of sixteen-hour days and profound respect for the middle-class morality of the era despite her obvious deviancy from sexual norms especially.

In 2003, a short independent film based on Cullwick's diaries, On My Knees, was made by Kim Wood. It stars Melora Creager, of Rasputina.

Sources

- Judith Flanders. Inside the Victorian Home: A Portrait of Domestic Life in Victorian England. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Diane Atkinson. Love and Dirt: The Marriage of Arthur Munby and Hannah Cullwick. New York: Macmillan, 2003 (ISBN 0-333-78071-X).

- Barry Reay. Watching Hannah: Sexuality, Horror and Bodily De-formation in Victorian England. Reaktion, 2002. (ISBN 1-86189-119-9)

- Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sex in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge, 1995. (ISBN 0-415-90890-6)

- Liz Stanley, ed. The Diaries of Hannah Cullwick, Victorian Maidservant. Rutgers, 1984 (ISBN 0-8135-1070-8).