Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene,[lower-alpha 1] sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine, was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and its aftermath.[2] She is mentioned by name twelve times in the canonical gospels, more than most of the apostles and more than any other woman in the Gospels, other than Jesus' family. Mary's epithet Magdalene may mean that she came from the town of Magdala, a fishing town on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee.

Mary Magdalene | |

|---|---|

Mary Magdalene (c. 1524) by Andrea Solari, showing her as a Myrrhbearer | |

| Apostle to the Apostles | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches Eastern Orthodox Churches Oriental Orthodox Churches Anglican Communion Lutheranism other Protestant churches Baháʼí Faith |

| Canonized | pre-Congregation |

| Feast | July 22 |

| Attributes | Western: alabaster box of ointment Eastern: container of ointment (as a myrrhbearer), or holding a red egg (symbol of the resurrection); embracing the feet of Christ after the Resurrection |

| Patronage | Apothecaries Arahal, Spain Atrani, Italy Casamicciola Terme, Ischia contemplative life converts glove makers hairdressers Kawit, Cavite Amadeo, Cavite Magdalena, Laguna Order of Preachers perfumeries people ridiculed for their piety pharmacists Pililla, Rizal penitent sinners tanners sexual temptation women |

The Gospel of Luke 8:2–3 lists Mary Magdalene as one of the women who traveled with Jesus and helped support his ministry "out of their resources", indicating that she was probably relatively wealthy. The same passage also states that seven demons had been driven out of her, a statement which is repeated in the longer ending of Mark. In all four canonical gospels, Mary Magdalene is a witness to the crucifixion of Jesus and, in the Synoptic Gospels, she is also present at his burial. All four gospels identify her, either alone or as a member of a larger group of women which includes Jesus's mother, as the first to witness the empty tomb,[2] and the first to witness Jesus's resurrection.[3]

For these reasons, Mary Magdalene is known in some Christian traditions as the "apostle to the apostles". Mary Magdalene is a central figure in later Gnostic Christian writings, including the Dialogue of the Savior, the Pistis Sophia, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Mary. These texts portray Mary Magdalene as an apostle, as Jesus's closest and most beloved disciple and the only one who truly understood his teachings. In the Gnostic texts, or Gnostic gospels, Mary Magdalene's closeness to Jesus results in tension with another disciple, Peter, due to her sex and Peter's jealousy of special teachings given to her; some fiction portrays her as the wife of Jesus.

The portrayal of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute began after a series of Easter sermons delivered in 591, when Pope Gregory I conflated Mary Magdalene, who is introduced in Luke 8:2, with Mary of Bethany (Luke 10:39) and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus's feet in Luke 7:36–50. This resulted in a widespread belief that she was a repentant prostitute or promiscuous woman.[4][2] Elaborate medieval legends from western Europe tell exaggerated tales of Mary Magdalene's wealth and beauty, as well as her alleged journey to southern France. The identification of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany and the unnamed "sinful woman" was a major controversy in the years leading up to the Reformation and some Protestant leaders rejected it. During the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church emphasized Mary Magdalene as a symbol of penance. In 1969, the identification of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany and the "sinful woman" was removed from the General Roman Calendar by Pope Paul VI, but the view of her as a former prostitute has persisted in popular culture.

Mary Magdalene is considered to be a saint by the Catholic, and by the Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran churches. In 2016 Pope Francis raised the level of liturgical memory on July 22 from memorial to feast, and for her to be referred as the 'Apostle of the apostles'.[5] Other Protestant churches honor her as a heroine of the faith. The Eastern Orthodox churches also commemorate her on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers, the Orthodox equivalent of one of the Western Three Marys traditions.

Life

It is widely accepted among secular historians that, like Jesus, Mary Magdalene was a real historical figure.[6][7][8] Nonetheless, very little is known about her life.[9] Unlike Paul the Apostle, Mary Magdalene has left behind no writings of her own.[10] She is never mentioned in any of the Pauline epistles or in any of the general epistles.[11][12] The earliest and most reliable sources about her life are the three Synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke, which were all written during the first century AD.[13][14][15]

During Jesus's ministry

Mary Magdalene's epithet Magdalene (ἡ Μαγδαληνή; literally "the Magdalene") most likely means that she came from Magdala,[16][17][1][lower-alpha 2] a village on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee that was primarily known in antiquity as a fishing town.[16][21][22] Mary was, by far, the most common Jewish given name for females during the first century,[16][lower-alpha 3] so it was necessary for the authors of the gospels to call her Magdalene in order to distinguish her from the other women named Mary who followed Jesus.[16] Although the Gospel of Mark, the earliest surviving gospel, does not mention Mary Magdalene until Jesus's crucifixion,[27] the Gospel of Luke 8:2–3 provides a brief summary of her role during his ministry:[28]

Soon afterwards he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. The twelve were with him, as well as some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, and Susanna, and many others, who provided for them out of their resources.

The statement that Mary had been possessed by seven demons is repeated in Mark 16:9,[32] part of the "longer ending" of that gospel – this is not found in the earliest manuscripts, and is actually a second-century addition to the original text, possibly based on the Gospel of Luke.[32][33] In the first century, demons were widely believed to be the cause of physical and psychological illness.[34][29][30] Bruce Chilton, a scholar of early Christianity, states that the reference to the number of demons being "seven" may mean that Mary had to undergo seven exorcisms, probably over a long period of time, due to the first six being partially or wholly unsuccessful.[31]

Bart D. Ehrman, a New Testament scholar and historian of early Christianity, contends that the number seven may be merely symbolic,[30] since, in Jewish tradition, seven was the number of completion,[30] so the statement that Mary was possessed by seven demons may simply mean she was completely overwhelmed by their power.[30] In either case, Mary must have suffered from severe emotional or psychological trauma in order for an exorcism of this kind to have been perceived as necessary.[29][30] Consequently, her devotion to Jesus on account of this healing must have been very strong.[16][35][36] The gospel-writers normally relish giving dramatic descriptions of Jesus's public exorcisms, with the possessed person wailing, thrashing, and tearing his or her clothes in front of a crowd.[37] The fact that Mary's exorcism is given so little attention may indicate that it was either done in private or that it was not seen as particularly dramatic.[37]

Because Mary is listed as one of the women who were supporting Jesus's ministry financially, she must have been relatively wealthy.[16][38] The places where she and the other women are mentioned throughout the gospels strongly indicate that they were vital to Jesus's ministry[39][40][41][42] and the fact that Mary Magdalene always appears first, whenever she is listed in the Synoptic Gospels as a member of a group of women, indicates that she was seen as the most important out of all of them.[43][44][45] Carla Ricci notes that, in lists of the disciples, Mary Magdalene occupies a similar position among Jesus's female followers as Simon Peter does among the male apostles.[45]

The fact that women played such an active and important role in Jesus's ministry was not entirely radical or even unique;[40][42] inscriptions from a synagogue in Aphrodisias in Asia Minor from around the same time period reveal that many of the major donors to the synagogue were women.[40] Jesus's ministry did bring women greater liberation than they would have typically held in mainstream Jewish society.[46][42] Jesus taught that, in the imminent kingdom of God, there would be a reversal of roles and those who had been oppressed would be exalted.[47] According to Ehrman, this idea would have probably been particularly appealing and empowering to women of the time, such as Mary Magdalene, who may have felt oppressed by traditional attitudes to gender roles.[48]

Witness to Jesus's crucifixion and burial

All four canonical gospels agree that Mary Magdalene, along with several other women, watched Jesus's crucifixion from a distance.[50] Mark 15:40 lists the names of the women present as Mary Magdalene; Mary, mother of James; and Salome.[50] Matthew 27:55–56 lists Mary Magdalene, Mary mother of James and Joseph, and the unnamed mother of the sons of Zebedee (who may be the same person Mark calls Salome).[50] Luke 23:49 mentions a group of women watching the crucifixion, but does not give any of their names.[50] John 19:25 lists Mary, mother of Jesus, her sister, Mary, wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene as witnesses to the crucifixion.[50]

Virtually all reputable historians agree that Jesus was crucified by the Romans under the orders of Pontius Pilate.[51][52][53][54][55] Nonetheless, the gospels' accounts of Jesus's crucifixion differ considerably[56] and most secular historians agree that some of the details in the accounts have been altered to fit their authors' theological agendas.[56] Ehrman states that the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other women at the cross is probably historical because Christians would have been unlikely to make up that the main witnesses to the crucifixion were women[57] and also because their presence is independently attested in both the Synoptic Gospels and in the Gospel of John.[58] Maurice Casey concurs that the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other women at the crucifixion of Jesus may be recorded as a historical fact.[6] According to E. P. Sanders, the reason why the women watched the crucifixion even after the male disciples had fled may have been because they were less likely to be arrested, because they were braver than the men, or because of some combination thereof.[59]

All four canonical gospels, as well as the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, agree that Jesus's body was taken down from the cross and buried by a man named Joseph of Arimathea.[50] Mark 15:47 lists Mary Magdalene and Mary, mother of Joses as witnesses to the burial of Jesus.[50] Matthew 27:61 lists Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" as witnesses.[50] Luke 23:55 mentions "the women who had followed him from Galilee", but does not list any of their names.[50] John 19:39–42 does not mention any women present during Joseph's burial of Jesus,[50] but does mention the presence of Nicodemus, a Pharisee with whom Jesus had a conversation near the beginning of the gospel.[50] Ehrman, who previously accepted the story of Jesus's burial as historical, now rejects it as a later invention on the basis that Roman governors almost never allowed for executed criminals to be given any kind of burial[61] and Pontius Pilate in particular was not "the sort of ruler who would break with tradition and policy when kindly asked by a member of the Jewish council to provide a decent burial for a crucified victim."[62]

John Dominic Crossan has controversially argued that Jesus's body was probably eaten by wild dogs.[62][63] Ehrman notes that this was the most common fate for victims of crucifixion,[64] but states that it is impossible to know for certain what actually happened to Jesus's body once it was removed from the cross.[65] Casey argues that Jesus really was given a proper burial by Joseph of Arimathea,[66] noting that, on some very rare occasions, Roman governors did release the bodies of executed prisoners for burial.[67] Nonetheless, he rejects that Jesus could have been interred in an expensive tomb with a stone rolled in front of it like the one described in the gospels,[68] leading him to conclude that Mary and the other women must not have actually seen the tomb.[68] Sanders affirms Jesus's burial by Joseph of Arimathea in the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other female followers as completely historical.[69]

Resurrection of Jesus

The earliest description of Jesus's post-resurrection appearances is a quotation of a pre-Pauline creed preserved by Paul the Apostle in 1 Corinthians 15:3–8, which was written roughly 20 years before any of the gospels.[73] This passage makes no mention of Mary Magdalene, the other women, or the story of the empty tomb at all,[74][75] but rather credits Simon Peter with having been the first to see the risen Jesus.[74][76][77] Despite this, all four canonical gospels, as well as the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, agree that Mary Magdalene, either alone or as a member of a group, was the first person to discover that Jesus's tomb was empty.[58][78] Nonetheless, the details of the accounts differ drastically.[71]

According to Mark 16:1–8, the earliest account of the discovery of the empty tomb, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome went to the tomb just after sunrise a day and half after Jesus's burial and found that the stone had already been rolled away.[71][72][79] They went inside and saw a young man dressed in white, who told them that Jesus had risen from the dead and instructed them to tell the male disciples that he would meet them in Galilee.[70][71][72] Instead, the women ran away and told no one, because they were too afraid.[70][71][72] The original text of the gospel ends here, without the resurrected Jesus ever actually making an appearance to anyone.[70][72][80] Casey argues that the reason for this abrupt ending may be because the Gospel of Mark is an unfinished first draft.[70]

According to Matthew 28:1–10, Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" went to the tomb.[70][71][72] An earthquake occurred and an angel dressed in white descended from Heaven and rolled aside the stone as the women were watching.[70][71][72] The angel told them that Jesus had risen from the dead.[71][72][70] Then the risen Jesus himself appeared to the women as they were leaving the tomb and told them to tell the other disciples that he would meet them in Galilee.[70][71][72] According to Luke 24:1–12 a group of unnamed women went to the tomb and found the stone already rolled away, as in Mark.[71][72][81] They went inside and saw two young men dressed in white who told them that Jesus had risen from the dead.[71][72][81] Then they went and told the eleven remaining apostles, who dismissed their story as nonsense.[71][72][81] In Luke's account, Jesus never appears to the women,[71][72][82] but instead makes his first appearance to Cleopas and an unnamed "disciple" on the road to Emmaus. [71][72][82] Luke's narrative also removes the injunction for the women to tell the disciples to return to Galilee and instead has Jesus tell the disciples not to return to Galilee, but rather to stay in the precincts of Jerusalem.[82][83]

Mary Magdalene's role in the resurrection narrative is greatly increased in the account from the Gospel of John.[78][85] According to John 20:1–10, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb alone when it was still dark and saw that the stone had already been rolled away.[78][84][86] She did not see anyone, but immediately ran to tell Peter and the "beloved disciple",[78][86] who came with her to the tomb and confirmed that it was empty,[78][85] but returned home without seeing the risen Jesus.[85][78] According to John 20:11–18, Mary, now alone in the garden outside the tomb, saw two angels sitting where Jesus's body had been.[78] Then the risen Jesus approached her.[78][87] She at first mistook him for the gardener,[85][78] but, after she heard him say her name, she recognized him and cried out "Rabbouni!" (which is Aramaic for "teacher").[78][85] His next words may be translated as "Don't touch me, for I have not yet ascended to my Father" or "Stop clinging to me, [etc.]" the latter more probable in view of the grammar (negated present imperative: stop doing something already in progress) as well as Jesus' challenge to Thomas a week later (see John 20:24–29[88][80] Jesus then sent her to tell the other apostles the good news of his resurrection.[85][78] The Gospel of John therefore portrays Mary Magdalene as the first apostle, the apostle sent to the apostles.[85][78]

Because scribes were unsatisfied with the abrupt ending of the Gospel of Mark, they wrote several different alternative endings for it.[89] In the "shorter ending", which is found in very few manuscripts, the women go to "those around Peter" and tell them what they had seen at the tomb, followed by a brief declaration of the gospel being preached from east to west.[89] This "very forced" ending contradicts the last verse of the original gospel, stating that the women "told no one".[89] The "longer ending", which is found in most surviving manuscripts, is an "amalgam of traditions" containing episodes derived from the other gospels.[89] First, it describes an appearance by Jesus to Mary Magdalene alone (as in the Gospel of John),[89] followed by brief descriptions of him appearing to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (as in the Gospel of Luke) and to the eleven remaining disciples (as in the Gospel of Matthew).[89]

In a book published in 2006, Ehrman states that "it appears virtually certain" that the stories of the empty tomb, regardless of whether or not they are accurate, can definitely be traced back to the historical Mary Magdalene,[90] saying that, in Jewish society, women were regarded as unreliable witnesses and were forbidden from giving testimony in court,[91] so early Christians would have had no motive to make up a story about a woman being the first to discover the empty tomb.[91] In fact, if they had made the story up, they would have had strong motivation to make Peter, Jesus's closest disciple while he was alive, the discoverer of the tomb instead.[91] He also says that the story of Mary Magdalene discovering the empty tomb is independently attested in the Synoptics, the Gospel of John, and in the Gospel of Peter.[92] N. T. Wright states that "it is, frankly, impossible to imagine that [the women at the tomb] were inserted into the tradition after Paul's day."[93][6]

Casey challenges this argument, contending that the women at the tomb are not legal witnesses, but rather heroines in line with a long Jewish tradition.[6] He contends that the story of the empty tomb was invented by either the author of the Gospel of Mark or by one of his sources, based on the historically genuine fact that the women really had been present at Jesus's crucifixion and burial.[6] In a book published in 2014, Ehrman rejects his own previous argument,[94] stating that the story of the empty tomb can only be a later invention because there is virtually no possibility that Jesus's body could have been placed in any kind of tomb[94] and, if Jesus was never buried, then no one alive at the time could have said that his non-existent tomb had been found empty.[94] He concludes that the idea that early Christians would have had "no motive" to make up the story simply "suffers from a poverty of imagination"[95] and that they would have had all kinds of possible motives,[96] especially since women were overrepresented in early Christian communities and women themselves would have had strong motivation to make up a story about other women being the first to find the tomb.[97] He does conclude later, however, that Mary Magdalene must have been one of the people who had an experience in which she thought she saw the risen Jesus,[98] citing her prominence in the gospel resurrection narratives and her absence everywhere else in the gospels as evidence.[98]

Apocryphal early Christian writings

New Testament apocrypha writings mention Mary Magdalene. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians. However, they were never admitted to the canon of the New Testament. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches generally do not view these writings as part of the Bible.[99] In these apocryphal texts, Mary Magdalene is portrayed as a visionary and leader of the early movement whom Jesus loved more than he loved the other disciples.[100] These texts were written long after the death of the historical Mary Magdalene.[13][10] They are not regarded by bible scholars as reliable sources of information about her life.[13][10][101] Sanders summarizes the scholarly consensus that:

"... very, very little in the apocryphal gospels could conceivably go back to the time of Jesus. They are legendary and mythological. Of all the apocryphal material, only some of the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas are worth consideration."[101]

Nonetheless, the texts have been frequently promoted in modern works as though they were reliable. Such works often support sensationalist statements about Jesus and Mary Magdalene's relationship.[102]

Dialogue of the Savior

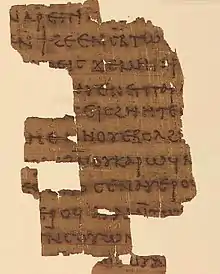

The earliest dialogue between Jesus and Mary Magdalene is probably the Dialogue of the Savior,[32] a badly damaged Gnostic text discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945.[32] The dialogue consists of a conversation between Jesus, Mary and two apostles - Thomas the Apostle and Matthew the Apostle.[104] In saying 53, the Dialogue attributes to Mary three aphorisms that are attributed to Jesus in the New Testament: "The wickedness of each day [is sufficient]. Workers deserve their food. Disciples resemble their teachers."[104] The narrator commends Mary stating "she spoke this utterance as a woman who understood everything."[104]

Pistis Sophia

The Pistis Sophia, possibly dating as early as the second century, is the best surviving of the Gnostic writings.[105] It was discovered in the eighteenth century in a large volume containing numerous early Gnostic treatises.[106] The document takes the form of a long dialogue in which Jesus answers his followers' questions.[107] Of the sixty-four questions, thirty-nine are presented by a woman who is referred to as Mary or Mary Magdalene. At one point, Jesus says, "Mary, thou blessed one, whom I will perfect in all mysteries of those of the height, discourse in openness, thou, whose heart is raised to the kingdom of heaven more than all thy brethren".[105] At another point, he tells her, "Well done, Mary. You are more blessed than all women on earth, because you will be the fullness of fullness and the completion of completion."[107] Simon Peter, annoyed at Mary's dominance of the conversation, tells Jesus, "My master, we cannot endure this woman who gets in our way and does not let any of us speak, though she talks all the time."[107] Mary defends herself, saying, "My master, I understand in my mind that I can come forward at any time to interpret what Pistis Sophia [a female deity] has said, but I am afraid of Peter, because he threatens me and hates our gender."[107] Jesus assures her, "Any of those filled with the spirit of light will come forward to interpret what I say: no one will be able to oppose them."[107] Mainstream Christianity maintains that God is one and denies the existence of other deities.

Gospel of Thomas

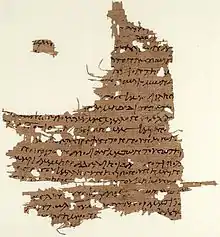

The Gospel of Thomas, usually dated to the late first or early second century, was among the ancient texts discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945.[109] The Gospel of Thomas consists entirely of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus.[110] Many of these sayings are similar to ones in the canonical gospels,[111] but others are completely unlike anything found in the New Testament.[110] Some scholars believe that at least a few of these sayings may authentically be traced back to the historical Jesus.[111][101] Two of the sayings reference a woman named "Mary", who is generally regarded as Mary Magdalene.[110] In saying 21, Mary herself asks Jesus the perfectly innocuous question, "Whom are your disciples like?"[112] Jesus responds, "They are like children who have settled in a field which is not theirs. When the owners of the field come, they will say, 'Let us have back our field.' They (will) undress in their presence in order to let them have back their field and to give it back to them". Following this, Jesus continues his explanation with a parable about the owner of a house and a thief, ending with the common rhetoric, "Whoever has ears to hear let him hear".

Mary's mention in saying 114, however, has generated considerable controversy:[112]

Simon Peter said to them: Let Mary go forth from among us, for women are not worthy of the life. Jesus said: Behold, I shall lead her, that I may make her male, in order that she also may become a living spirit like you males. For every woman who makes herself male shall enter into the kingdom of heaven.[109]

In the ancient world, it was almost universally believed that women were inferior to men[108] and that they were, in essence, "imperfect men" who had not fully developed.[108] When Peter challenges Mary's authority in this saying, he does so on the widely accepted premise that she is a woman and therefore an inferior human being.[113] When Jesus rebukes him for this, he bases his response on the same premise,[113] stating that Mary and all faithful women like her will become men and that salvation is therefore open to all, even those who are presently women.[113]

Gospel of Philip

The Gospel of Philip, dating from the second or third century, survives in part among the texts found in Nag Hammadi in 1945.[114] In a manner very similar to John 19:25–26, the Gospel of Philip presents Mary Magdalene among Jesus' female entourage, adding that she was his koinônos,[115] a Greek word variously translated in contemporary versions as partner, associate, comrade, companion:[116][115]

There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary, his mother, and her sister, and Magdalene, who was called his companion. His sister,[117] his mother and his companion were each a Mary.[114]

The Gospel of Philip uses cognates of koinônos and Coptic equivalents to refer to the literal pairing of men and women in marriage and sexual intercourse, but also metaphorically, referring to a spiritual partnership, and the reunification of the Gnostic Christian with the divine realm.[118] The Gospel of Philip also contains another passage relating to Jesus's relationship with Mary Magdalene.[115] The text is badly fragmented, and speculated but unreliable additions are shown in brackets:

And the companion of the saviour [was] Mary Magdalene. [Christ] loved Mary more than all the disciples, and used to kiss her often on the mouth. The rest of the disciples [were offended by it and expressed disapproval]. They said to him, "Why do you love her more than all of us?" The Saviour answered and said to them, "Why do I not love you like her? When a blind man and one who sees are both together in darkness, they are no different from one another. When the light comes, then he who sees will see the light, and he who is blind will remain in darkness."[119][114]

For early Christians, kissing did not have a romantic connotation and it was common for Christians to kiss their fellow believers as a way of greeting.[120][121][lower-alpha 4] This tradition is still practiced in many Christian congregations today and is known as the "kiss of peace".[115] Ehrman explains that, in the context of the Gospel of Philip, the kiss of peace is used as a symbol for the passage of truth from one person to another[122] and that it is not in any way an act of "divine foreplay".[121]

Gospel of Mary

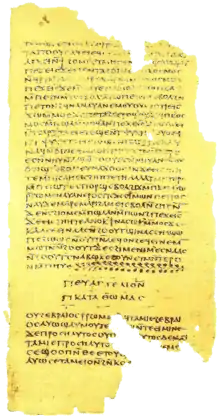

The Gospel of Mary is the only surviving apocryphal text named after a woman.[123] It contains information about the role of women in the early church.[124][125] The text was probably written over a century after the historical Mary Magdalene's death.[10] The text is not attributed to her and its author is anonymous.[10] Instead, it received its title because it is about her.[10] The main surviving text comes from a Coptic translation preserved in a fifth-century manuscript (Berolinensis Gnosticus 8052,1) discovered in Cairo in 1896.[126][127][125] As a result of numerous intervening conflicts, the manuscript was not published until 1955.[123] Roughly half the text of the gospel in this manuscript has been lost;[128][129] the first six pages and four from the middle are missing.[128][129] In addition to this Coptic translation, two brief third-century fragments of the gospel in the original Greek (P. Rylands 463 and P. Oxyrhynchus 3525) have also been discovered, which were published in 1938 and 1983 respectively.[127][125]

The first part of the gospel deals with Jesus's parting words to his followers after a post-resurrection appearance.[130] Mary first appears in the second part, in which she tells the other disciples, who are all in fright for their own lives: "Do not weep or grieve or be in doubt, for his grace will be with you all and will protect you. Rather, let us praise his greatness, for he has prepared us and made us truly human."[131] Unlike in the Gospel of Thomas, where women can only be saved by becoming men, in the Gospel of Mary, they can be saved just as they are.[132] Peter approaches Mary and asks her:[133]

"Sister we know that the Savior loved you more than the rest of woman. Tell us the words of the Savior which you remember which you know, but we do not, nor have we heard them". Mary answered and said, "What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you". And she began to speak to them these words: "I", she said, "I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to Him, Lord I saw you today in a vision".[129]

Mary then proceeds to describe the Gnostic cosmology in depth, revealing that she is the only one who has understood Jesus's true teachings.[134][135] Andrew the Apostle challenges Mary, insisting, "Say what you think about what she said, but I do not believe the savior said this. These teachings are strange ideas."[136][137] Peter responds, saying, "Did he really speak with a woman in private, without our knowledge? Should we all listen to her? Did he prefer her to us?"[136][137] Andrew and Peter's responses are intended to demonstrate that they do not understand Jesus's teachings[136][137] and that it is really only Mary who truly understands.[138][137] Matthew the Apostle comes to Mary's defense, giving a sharp rebuke to Peter:[136][137] "Peter, you are always angry. Now I see you arguing against this woman like an adversary. If the savior made her worthy, who are you to reject her? Surely the savior knows her well. That is why he loved her more than us."[139][137]

Borborite scriptures

The Borborites, also known as the Phibionites, were an early Christian Gnostic sect during the late fourth century who had numerous scriptures involving Mary Magdalene,[140][141][142] including The Questions of Mary, The Greater Questions of Mary, The Lesser Questions of Mary, and The Birth of Mary.[140] None of these texts have survived to the present,[140][142] but they are mentioned by the early Christian heretic-hunter Epiphanius of Salamis in his Panarion.[140][143][142][144] Epiphanius says that the Greater Questions of Mary contained an episode in which, during a post-resurrection appearance, Jesus took Mary to the top of a mountain, where he pulled a woman out of his side and engaged in sexual intercourse with her.[143][144] Then, upon ejaculating, Jesus drank his own semen and told Mary, "Thus we must do, that we may live."[143][141][144] Upon hearing this, Mary instantly fainted, to which Jesus responded by helping her up and telling her, "O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?"[143][141][144] This story was supposedly the basis for the Borborite Eucharist ritual in which they allegedly engaged in orgies and drank semen and menstrual blood as the "body and blood of Christ" respectively.[145][141] Ehrman casts doubt on the accuracy of Epiphanius's summary, commenting that "the details of Epiphanius's description sound very much like what you can find in the ancient rumor mill about secret societies in the ancient world".[143]

Legacy

Patristic era

Most of the earliest Church Fathers do not mention Mary Magdalene at all,[149][11][150] and those who do mention her usually only discuss her very briefly.[149][11][150] In his anti-Christian polemic The True Word, written between 170 and 180, the pagan philosopher Celsus declared that Mary Magdalene was nothing more than "a hysterical female... who either dreamt in a certain state of mind and through wishful thinking had a hallucination due to some mistaken notion (an experience which has happened to thousands), or, which is more likely, wanted to impress others by telling this fantastic tale, and so by this cock-and-bull story to provide a chance for other beggars."[151] The Church Father Origen (c. 184 – c. 253) defended Christianity against this accusation in his apologetic treatise Against Celsus, pointing to Matthew 28:1, which lists Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" both seeing the resurrected Jesus, thus providing a second witness.[152] Origen also preserves a statement from Celsus that some Christians in his day followed the teachings of a woman named "Mariamme", who is almost certainly Mary Magdalene.[153][154] Origen merely dismisses this, remarking that Celsus "pours on us a heap of names".[153]

Mary Magdalene has the reputation in Western Christianity as being a repentant prostitute or loose woman; however, these statements are not supported by the canonical gospels, which at no point imply that she had ever been a prostitute or in any way notable for a sinful way of life.[2][155][156] The misconception likely arose due to a conflation between Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany (who anoints Jesus's feet in John 11:1–12), and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus's feet in Luke 7:36–50.[2][155][157] As early as the third century, the Church Father Tertullian (c. 160 – 225) references the touch of "the woman which was a sinner" in effort to prove that Jesus "was not a phantom, but really a solid body."[152] This may indicate that Mary Magdalene was already being conflated with the "sinful woman" in Luke 7:36–50, though Tertullian never clearly identifies the woman of whom he speaks as Mary Magdalene.[152] A sermon attributed to Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170 – 235) refers to Mary of Bethany and her sister Martha seeking Jesus in the garden like Mary Magdalene in John 20, indicating a conflation between Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene.[158] The sermon describes the conflated woman as a "second Eve" who compensates for the disobedience of the first Eve through her obedience.[149][150] The sermon also explicitly identifies Mary Magdalene and the other women as "apostles".[85][159] The first clear identification of Mary Magdalene as a redeemed sinner comes from Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373).[160][161] Part of the reason for the identification of Mary Magdalene as a sinner may derive from the reputation of her birthplace, Magdala,[162] which, by the late first century, was infamous for its inhabitants' alleged vice and licentiousness.[162]

In one of his preserved sayings, Gregory of Nyssa (c. 330 – 395) identifies Mary Magdalene as "the first witness to the resurrection, that she might set straight again by her faith in the resurrection, what was turned over in her transgression."[163] Ambrose (c. 340 – 397), by contrast, not only rejected the conflation of Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and the anointing sinner,[164] but even proposed that the authentic Mary Magdalene herself was, in fact, two separate people:[164][165] one woman named Mary Magdalene who discovered the empty tomb and a different Mary Magdalene who saw the risen Christ.[164] Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430) entertained the possibility that Mary of Bethany and the unnamed sinner from Luke might be the same person,[166] but did not associate Mary Magdalene with either of them.[167] Instead, Augustine praised Mary Magdalene as "unquestionably... surpassingly more ardent in her love than these other women who had administered to the Lord".[167]

Early Middle Ages

A depiction of Mary Magdalene with thick body hair

.jpg.webp)

The unnamed "sinful woman" in Luke 7:36–50 is never identified as a prostitute[168] and, in Jewish society at the time the gospel was written, "sinful" could have simply meant that she "did not assiduously observe the law of Moses".[168] The notion of Mary Magdalene specifically being a former prostitute or loose woman dates to a narrative by Pope Gregory I ("Gregory the Great") made in an influential homily in around 591,[160][169][156] in which he not only identifies Magdalene with the anonymous sinner with the perfume in Luke's gospel and with Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus,[156] but also, for the first time, explicitly identifies her sins as ones of a sexual nature:[156]

She whom Luke calls the sinful woman, whom John calls Mary, we believe to be the Mary from whom seven devils were ejected according to Mark. What did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices? It is clear, that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts. What she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was now offering to God in a more praiseworthy manner. She had coveted with earthly eyes, but now through penitence these are consumed with tears. She displayed her hair to set off her face, but now her hair dries her tears. She had spoken proud things with her mouth, but in kissing the Lord's feet, she now planted her mouth on the Redeemer's feet. For every delight, therefore, she had had in herself, she now immolated herself. She turned the mass of her crimes to virtues, in order to serve God entirely in penance.

— Pope Gregory I (homily XXXIII)[169]

In Pope Gregory's interpretation, the seven demons expelled from Mary Magdalene by Jesus are transformed into the seven deadly sins of medieval Catholicism,[157][170] leading Mary "to be condemned not only for lust, but for pride and covetousness as well."[157] The aspect of the repentant sinner became almost equally significant as the disciple in her persona as depicted in Western art and religious literature, fitting well with the great importance of penitence in medieval theology. In subsequent religious legend, Mary's story became conflated with that of Mary of Egypt, a repentant prostitute who then lived as a hermit. With that, Mary's image was, according to Susan Haskins, author of Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor, "finally settled...for nearly fourteen hundred years,"[171] although in fact the most important late medieval popular accounts of her life describe her as a rich woman whose life of sexual freedom is purely for pleasure.[172] This composite depiction of Mary Magdalene was carried into the Mass texts for her feast day: in the Tridentine Mass, the collect explicitly identifies her as Mary of Bethany by describing Lazarus as her brother, and the Gospel is the story of the penitent woman anointing Jesus' feet.[173]

The "composite Magdalene" was never accepted by the Eastern Orthodox churches, who saw only Mary the disciple, and believed that after the Resurrection she lived as a companion to the Virgin Mary, and not even in the West was it universally accepted. The Benedictine Order always celebrated Mary of Bethany together with Martha and Lazarus of Bethany on July 29, while Mary Magdalene was celebrated on July 22.[174] Not only John Chrysostom in the East (Matthew, Homily 88), but also Ambrose (De virginitate 3,14; 4,15) in the West, when speaking of Mary Magdalene after the resurrection of Jesus Christ, far from calling her a harlot, suggest she was a virgin.[175] Starting in around the eighth century, Christian sources record mention of a church in Magdala purported to have been built on the site of Mary Magdalene's house, where Jesus exorcized her of the seven demons.[176]

In an eastern tradition supported by the western bishop and historian Gregory of Tours (c. 538 – 594), Mary Magdalene is said to have retired to Ephesus in Asia Minor with the virgin Mary, where they both lived out the rests of their lives.[177][178] Gregory states that Mary Magdalene was buried in the city of Ephesus.[178] Modestus, the Patriarch of Jerusalem from 630 until 634, describes a slightly different tradition that Mary Magdalene had come to Ephesus to live with the apostle John following the death of the Virgin Mary.[178]

Fictional biographies

Starting in early High Middle Ages, writers in western Europe began developing elaborate fictional biographies of Mary Magdalene's life, in which they heavily embellished upon the vague details given in the gospels.[179][180] Stories about noble saints were popular during this time period;[179] accordingly, tales of Mary Magdalene's wealth and social status became heavily exaggerated.[181][180] In the tenth century, Odo of Cluny (c. 880 – 942) wrote a sermon in which he described Mary as an extraordinarily wealthy noblewoman of royal descent.[182] Some manuscripts of the sermon record that Mary's parents were named Syrus and Eucharia[183] and one manuscript goes into great detail describing her family's purported land holdings in Bethany, Jerusalem, and Magdala.[183]

The theologian Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1080 – c. 1151) embellished this tale even further, reporting that Mary was a wealthy noblewoman who was married in "Magdalum",[183] but that she committed adultery, so she fled to Jerusalem and became a "public sinner" (vulgaris meretrix).[183] Honorius mentions that, out of love for Jesus, Mary repented and withdrew into a life of quiet isolation.[183] Under the influence of stories about other female saints, such as Mary of Egypt and Pelagia,[183] painters in Italy during the ninth and tenth centuries gradually began to develop the image of Mary Magdalene living alone in the desert as a penitent ascetic.[183][184] This portrayal became so popular that it quickly spread to Germany and England.[183] From the twelfth century, Abbot Hugh of Semur (died 1109), Peter Abelard (died 1142), and Geoffrey of Vendome (died 1132) all referred to Mary Magdalene as the sinner who merited the title apostolorum apostola (Apostle to the Apostles), with the title becoming commonplace during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.[185]

Alleged burial in France

In western Europe, elaborate and conflicting legends began to develop, which said that Mary Magdalene had travelled to southern France and died there.[186] Starting in around 1050, the monks of the Abbey of la Madaleine, Vézelay in Burgundy said they discovered Mary Magdalene's actual skeleton.[187][188] At first, the existence of the skeleton was merely asserted,[188] but, in 1265, the monks made a spectacular, public show of "discovering" it[188] and, in 1267, the bones were brought before the king of France himself, who venerated them.[188] On December 9, 1279, an excavation ordered by Charles II, King of Naples at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, Provence, led to the discovery of another purported burial of Mary Magdalene.[189][188] The shrine was purportedly found intact, with an explanatory inscription stating why the relics had been hidden.[190] Charles II commissioned the building of a new Gothic basilica on the site and, in return for providing accommodation for pilgrims, the town's residents were exempt from taxes.[191] Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume gradually displaced Vézelay in popularity and acceptance.[190]

The Golden Legend

The most famous account of Mary Magdalene's legendary life comes from The Golden Legend, a collection of medieval saints stories compiled in around the year 1260 by the Italian writer and Dominican friar Jacobus de Voragine (c. 1230 – 1298).[192][188][193] In this account, Mary Magdalene is, in Ehrman's words, "fabulously rich, insanely beautiful, and outrageously sensual",[192] but she gives up her life of wealth and sin to become a devoted follower of Jesus.[192][194] Fourteen years after Jesus's crucifixion, some pagans throw Mary, Martha, Lazarus (who, in this account, is their brother due to a conflation with Mary of Bethany), and two other Christians named Maximin and Cedonius onto a rudderless boat in the Mediterranean Sea to die.[192][193] Miraculously, however, the boat washes ashore at Marseille in southern France.[192][193] Mary persuades the governor of the city not to offer sacrifices to a pagan god[192] and later persuades him to convert to Christianity after she proves the Christian God's power by successfully praying to Him to make the governor's wife pregnant.[192][193] The governor and his wife sail for Rome to meet the apostle Peter in person,[192] but their ship is struck by a storm, which causes the wife to go into labor.[192] The wife dies in childbirth and the governor leaves her on an island with the still-living infant at her breast.[192] The governor spends two years with Peter in Rome[192] and, on his way home, he stops at the same island to discover that, due to Mary Magdalene's miraculous long-distance intercession, his child has survived for two years on his dead mother's breast milk.[195] Then the governor's wife rises from the dead and tells him that Mary Magdalene has brought her back.[11] The whole family returns to Marseille, where they meet Mary again in person.[11] Mary herself spends the last thirty years of her life alone as a penitent ascetic in a cave in a desert in the French region of Provence.[193][196][197][198][199] At every canonical hour, the angels come and lift her up to hear their songs in Heaven.[193] On the last day of her life, Maximin, now the bishop of Aix, comes to her and gives her the Eucharist.[193] Mary cries tears of joy[193] and, after taking it, she lies down and dies.[193] De Voragine gives the common account of the transfer of Mary Magdalene's relics from her sepulchre in the oratory of Saint Maximin at Aix-en-Provence to the newly founded Vézelay;[200] the transportation of the relics is entered as undertaken in 771 by the founder of the abbey, identified as Gerard, Duke of Burgundy.[201]

Spouse of John the Evangelist

The monk and historian Domenico Cavalca (c. 1270 – 1342), citing Jerome, suggested that Mary Magdalene was betrothed to John the Evangelist: "I like to think that the Magdalene was the spouse of John, not affirming it... I am glad and blythe that St Jerome should say so".[202] They were sometimes thought to be the couple at the Wedding at Cana, though the Gospel accounts say nothing of the ceremony being abandoned. In the Golden Legend, De Voragine dismisses talk of John and Mary being betrothed and John leaving his bride at the altar to follow Jesus as nonsense.[201]

Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

The thirteenth-century Cistercian monk and chronicler Peter of Vaux de Cernay said it was part of Catharist belief that the earthly Jesus Christ had a relationship with Mary Magdalene, described as his concubine: "Further, in their secret meetings they said that the Christ who was born in the earthly and visible Bethlehem and crucified at Jerusalem was "evil", and that Mary Magdalene was his concubine – and that she was the woman taken in adultery who is referred to in the Scriptures."[208] A document, possibly written by Ermengaud of Béziers, undated and anonymous and attached to his Treatise against Heretics,[209] makes a similar statement:[210]

Also they [the Cathars] teach in their secret meetings that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Christ. She was the Samaritan woman to whom He said, "Call thy husband". She was the woman taken into adultery, whom Christ set free lest the Jews stone her, and she was with Him in three places, in the temple, at the well, and in the garden. After the Resurrection, He appeared first to her.[211]

In the middle of the fourteenth century, a Dominican friar wrote a biography of Mary Magdalene in which he described her brutally mutilating herself after giving up prostitution,[204] clawing at her legs until they bled, tearing out clumps of her hair, and beating her face with her fists and her breasts with stones.[204] This portrayal of her inspired the sculptor Donatello (c. 1386 – 1466) to portray her as a gaunt and beaten ascetic in his wooden sculpture Penitent Magdalene (c. 1454) for the Florence Baptistery.[204] In 1449, King René d'Anjou gave to Angers Cathedral the amphora from Cana in which Jesus changed water to wine, acquiring it from the nuns of Marseilles, who told him that Mary Magdalene had brought it with her from Judea, relating to the legend where she was the jilted bride at the wedding after which John the Evangelist received his calling from Jesus.[212]

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In 1517, on the brink of the Protestant Reformation, the leading French Renaissance humanist Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples published his book De Maria Magdalena et triduo Christi disceptatio (Disputation on Mary Magdalene and the Three Days of Christ), in which he argued against the conflation of Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and the unnamed sinner in Luke.[175][214] Various authors published a flurry of books and pamphlets in response, the vast majority of which opposed Lefèvre d'Étaples.[175][215] In 1521, the theology faculty of the Sorbonne formally condemned the idea that the three women were separate people as heretical,[175][215] and debate died down, overtaken by the larger issues raised by Martin Luther.[175][215] Luther and Huldrych Zwingli (1484 – 1531) both supported the composite Magdalene.[216] Luther, whose views on sexuality were much more liberal than those of his fellow reformers,[217] reportedly once joked to a group of friends that "even pious Christ himself" had committed adultery three times: once with Mary Magdalene, once with the Samaritan woman at the well, and once with the adulteress he had let off so easily.[218] Because the cult of Mary Magdalene was inextricably associated with the Catholic teaching of the intercession of saints,[219] it came under particularly harsh criticism by Protestant leaders.[219] Zwingli demanded for the cult of Mary Magdalene to be abolished and all images of her to be destroyed.[219] John Calvin (1509 – 1564) not only rejected the composite Magdalene,[219][216] but criticized Catholics as ignorant for having ever believed in it.[219]

During the Counter-Reformation, Roman Catholicism began to strongly emphasize Mary Magdalene's role as a penitent sinner.[220][221][222] Her medieval role as a patron and advocate became minimized[220] and her penitence became regarded as her most important aspect, especially in France and in the Catholic portions of southern Germany.[220] A massive number of Baroque paintings and sculptures depict the penitent Magdalene,[220][223] often showing her naked or partially naked, with a strong emphasis on her erotic beauty.[213] Poems about Mary Magdalene's repentance were also popular.[224] Estates of nobles and royalty in southern Germany were equipped with so-called "Magdalene cells", small, modest hermitages that functioned as both chapels and dwellings, where the nobility could retreat to find religious solace.[225] They were usually located away in wild areas away from the rest of the property[226] and their exteriors were designed to suggest vulnerability.[226]

Modern era

Not she with trait'rous kiss her Saviour stung,

Not she denied Him with unholy tongue;

She, while apostles shrank, could danger brave,

Last at His cross, and earliest at His grave.— Eaton Stannard Barrett, Woman (1810), Part I, lines 141–145

Because of the legends saying that Mary Magdalene had been a prostitute, she became the patroness of "wayward women", and, in the eighteenth century, moral reformers established Magdalene asylums to help save women from prostitution.[227] Edgar Saltus's historical fiction novel Mary Magdalene: A Chronicle (1891) depicts her as a heroine living in a castle at Magdala, who moves to Rome becoming the "toast of the tetrarchy", telling John the Baptist she will "drink pearls... sup on peacock's tongues".[228][229]

The common identification of Mary Magdalene with other New Testament figures was omitted in the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar, with the comment regarding her liturgical celebration on July 22: "No change has been made in the title of today's memorial, but it concerns only Saint Mary Magdalene, to whom Christ appeared after his resurrection. It is not about the sister of Saint Martha, nor about the sinful woman whose sins the Lord forgave (Luke 7:36–50)."[230] Elsewhere it said of the Roman liturgy of July 22 that "it will make mention neither of Mary of Bethany nor of the sinful woman of Luke 7:36–50, but only of Mary Magdalene, the first person to whom Christ appeared after his resurrection".[231] According to historian Michael Haag, these changes were a quiet admission from the Vatican that the Church's previous teaching of Mary Magdalene as a repentant whore had been wrong.[232] Mary of Bethany's feast day and that of her brother Lazarus is now on July 29, the memorial of their sister Martha.[233]

Nonetheless, despite the Vatican's rejection of it, the view of Mary as a repentant prostitute only grew more prevalent in popular culture.[234][235][236] She is portrayed as one in Nikos Kazantzakis's 1955 novel The Last Temptation of Christ and Martin Scorsese's 1988 film adaptation of it,[235] in which Jesus, as he is dying on the cross, has a vision from Satan of what it would be like if he married Mary Magdalene and raised a family with her instead of dying for humanity's sins.[235] Mary is likewise portrayed as a reformed prostitute in Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice's 1971 rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar.[237][234][238] In Superstar, Mary describes her sexual attraction to Jesus in the song "I Don't Know How to Love Him", which shocked many of the play's original viewers.[239][234] Ki Longfellow's novel The Secret Magdalene (2005) draws on the Gnostic gospels and other sources to portray Mary as a brilliant and dynamic woman who studies at the fabled library of Alexandria, and shares her knowledge with Jesus.[240] Lady Gaga's song "Judas" (2011) is sung from Mary's perspective, portraying her as a prostitute who is "beyond repentance".[241]

The 2018 film Mary Magdalene, starring Rooney Mara as the eponymous character, sought to reverse the centuries-old portrayal of Mary Magdalene as a repentant prostitute, while also combating the conspiracy claims of her being Jesus's wife or sexual partner.[242][243][244] Instead, the film portrays her as Jesus's closest disciple[242][243][244] and the only one who truly understands his teachings.[242][243][244] This portrayal is partially based on the Gnostic Gospel of Mary Magdalene.[244] The film, which described as having a "strongly feminist bent",[243] was praised for its music score and cinematography,[245] its surprising faithfulness to the Biblical narrative,[243] and its acting,[243][242] but was criticized as slow-moving,[242][243][245] overwritten,[245] and too solemn to be believable.[242][245] It was also criticized by many Christians, who were offended by the film's use of extracanonical source material.[244]

In Western art

_-_copia.jpg.webp)

by Domenico Tintoretto

The early notion of Mary Magdalene as a sinner and adulteress was reflected in Western medieval Christian art, where she was the most commonly depicted female figure after the Virgin Mary. She may be shown either as very extravagantly and fashionably dressed, unlike other female figures wearing contemporary styles of clothes, or alternatively as completely naked but covered by very long blonde or reddish-blonde hair. The latter depictions represent the Penitent Magdalene, according to the medieval legend that she had spent a period of repentance as a desert hermit after leaving her life as a follower of Jesus.[186][247] Her story became conflated in the West with that of Mary of Egypt, a fourth-century prostitute turned hermit, whose clothes wore out and fell off in the desert.[186] The widespread artistic representations of Mary Magdalene in tears are the source of the modern English word maudlin,[248][249][250] meaning "sickeningly sentimental or emotional".[248]

In medieval depictions Mary's long hair entirely covers her body and preserves her modesty (supplemented in some German versions such as one by Tilman Riemenschneider by thick body hair),[251][252] but, from the sixteenth century, some depictions, like those by Titian, show part of her naked body, the amount of nudity tending to increase in successive periods. Even if covered, she often wears only a drape pulled around her, or an undergarment. In particular, Mary is often shown naked in the legendary scene of her "Elevation", where she is sustained in the desert by angels who raise her up and feed her heavenly manna, as recounted in the Golden Legend.[251]

Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross during the Crucifixion appears in an eleventh-century English manuscript "as an expressional device rather than a historical motif", intended as "the expression of an emotional assimilation of the event, that leads the spectator to identify himself with the mourners".[253] Other isolated depictions occur, but, from the thirteenth century, additions to the Virgin Mary and John as the spectators at the Crucifixion become more common, with Mary Magdalene as the most frequently found, either kneeling at the foot of the cross clutching the shaft, sometimes kissing Christ's feet, or standing, usually at the left and behind Mary and John, with her arms stretched upwards towards Christ in a gesture of grief, as in a damaged painting by Cimabue in the upper church at Assisi of c. 1290. A kneeling Magdalene by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1305) was especially influential.[254] As Gothic painted crucifixions became crowded compositions, the Magdalene became a prominent figure, with a halo and identifiable by her long unbound blonde hair, and usually a bright red dress. As the swooning Virgin Mary became more common, generally occupying the attention of John, the unrestrained gestures of Magdalene increasingly represented the main display of the grief of the spectators.[255]

According to Robert Kiely, "No figure in the Christian Pantheon except Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist has inspired, provoked, or confounded the imagination of painters more than the Magdalene".[256] Apart from the Crucifixion, Mary was often shown in scenes of the Passion of Jesus, when mentioned in the Gospels, such as the Crucifixion, Christ Carrying the Cross and Noli me Tangere, but usually omitted in other scenes showing the Twelve Apostles, such as the Last Supper. As Mary of Bethany, she is shown as present at the Resurrection of Lazarus, her brother, and in the scene with Jesus and her sister Martha, which began to be depicted often in the seventeenth century, as in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Velázquez.[257]

Noli me tangere fresco by Fra Angelico

Noli me tangere fresco by Fra Angelico.jpg.webp) Mary Magdalene Reading (c. 1500–1510) by Piero di Cosimo

Mary Magdalene Reading (c. 1500–1510) by Piero di Cosimo Noli me tangere (c. 1512) by Titian

Noli me tangere (c. 1512) by Titian Mary Magdalene (early 1500s) by Ambrosius Benson

Mary Magdalene (early 1500s) by Ambrosius Benson Magdalena Penitente (early 1500s) by Giampietrino

Magdalena Penitente (early 1500s) by Giampietrino Mary Magdalene (1615) by Juan Bautista Maíno

Mary Magdalene (1615) by Juan Bautista Maíno Penitent Magdalene (c. 1576-1578) by El Greco

Penitent Magdalene (c. 1576-1578) by El Greco Mary Magdalene (1615–1616 or 1620–1625) by Artemisia Gentileschi

Mary Magdalene (1615–1616 or 1620–1625) by Artemisia Gentileschi St Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (c. 1619–1620) by Peter Paul Rubens

St Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (c. 1619–1620) by Peter Paul Rubens Mary Magdalene (1641) by José de Ribera

Mary Magdalene (1641) by José de Ribera Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (c. 1640) by Georges de La Tour

Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (c. 1640) by Georges de La Tour Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene (between 1640 and 1650) by Pietro da Cortona

Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene (between 1640 and 1650) by Pietro da Cortona The Magdalene (before 1792) by George Romney

The Magdalene (before 1792) by George Romney Mary Magdalene (1858–1860) by Frederick Sandys

Mary Magdalene (1858–1860) by Frederick Sandys Christ and Mary Magdalene (1890) by Albert Edelfelt in a Finnish locale

Christ and Mary Magdalene (1890) by Albert Edelfelt in a Finnish locale

Religious views

Eastern Orthodox

The Eastern Orthodox Church has never identified Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany or the "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus in Luke 7:36–50[258] and has always taught that Mary was a virtuous woman her entire life, even before her conversion.[258] They have never celebrated her as a penitent.[258] Mary Magdalene's image did not become conflated with other women mentioned in Biblical texts until Pope Gregory the Great's sermon in the sixth century, and even then this only occurred in Western traditions. Instead, she has traditionally been honored as a "Myrrhbearer" (Μυροφόρος; the equivalent of the western Three Marys)[259] and "Equal to the Apostles" (ἰσαπόστολος).[259] For centuries, it has been the custom of many Eastern Orthodox Christians to share dyed and painted eggs, particularly on Easter Sunday. The eggs represent new life, and Christ bursting forth from the tomb. Among Eastern Orthodox Christians this sharing is accompanied by the proclamation "Christ is risen!" One folk tradition concerning Mary Magdalene says that following the death and resurrection of Jesus, she used her position to gain an invitation to a banquet given by the Roman Emperor Tiberius. When she met him, she held a plain egg in her hand and exclaimed, "Christ is risen!" The Emperor laughed, and said that Christ rising from the dead was as likely as the egg in her hand turning red while she held it. Before he finished speaking, the egg in her hand turned a bright red and she continued proclaiming the Gospel to the entire imperial house.[260]

Roman Catholicism

During the Counter Reformation and Baroque periods (late 16th and 17th centuries), the description "penitent" was added to the indication of her name on her feast day, July 22. It had not yet been added at the time of the Tridentine Calendar of 1569 and is no longer found in the present General Roman Calendar but, once added, it remained until the General Roman Calendar of 1960.[261] The Gospel reading in the Tridentine Mass was Luke 7:36–50 (the sinful woman anointing the feet of Jesus), while in the present version of the Roman Rite of Mass it is John 20:1–2, 11–8 (meeting of Mary Magdalene with Jesus after his resurrection).[262][263][264]

According to Darrell Bock, the title of apostola apostolorum first appears in the 10th century,[159] but Katherine Ludwig Jansen says she found no reference to it earlier than the 12th, by which time it was already commonplace.[265] She mentions in particular Hugh of Cluny (1024–1109), Peter Abelard (1079–1142), and Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) among those who gave Mary Magdalene the title of apostolorum apostola (apostle of the apostles). Jane Schaberg adds Geoffrey of Vendôme (c. 1065/70–1132).[266]

The equivalent of the phrase apostolorum apostola may have appeared already in the 9th century. Chapter XXVII of the Life of Mary Magdalene attributed to Hrabanus Maurus (c. 780 – 4 February 856) is headed: Ubi Magdalenam Christus ad apostolos mittit apostolam (Wherein Christ sends Magdalene as an apostle to the apostles).[267] The same chapter says she did not delay in exercising the office of apostolate with which he had been honoured (apostolatus officio quo honorata fuerat fungi non distulit).[268] Raymond E. Brown, commenting on this fact, remarks that Hrabanus Maurus frequently applies the word "apostle" to Mary Magdalene in this work.[269] However the work is actually no earlier than the 12th century.[270] Because of Mary Magdalene's position as an apostle, though not one of those who became official witnesses to the resurrection, the Catholic Church honoured her by reciting the Gloria on her feast day, the only woman to be so honoured apart from Mary, the mother of Jesus.[271] In his apostolic letter Mulieris Dignitatem ("On the dignity and vocation of women", parts 67–69) dated August 15, 1988, Pope John Paul II dealt with the Easter events in relation to the women being present at the tomb after the Resurrection, in a section entitled 'First Witnesses of the Resurrection':

The women are the first at the tomb. They are the first to find it empty. They are the first to hear 'He is not here. He has risen, as he said.'[Mt 28:6] They are the first to embrace his feet.[cf. Mt 28:9] The women are also the first to be called to announce this truth to the Apostles.[Mt 28:1–10] [Lk 24:–11] The Gospel of John (cf. also Mk 16:9 emphasizes the special role of Mary Magdalene. She is the first to meet the Risen Christ. [...] Hence she came to be called "the apostle of the Apostles". Mary Magdalene was the first eyewitness of the Risen Christ, and for this reason she was also the first to bear witness to him before the Apostles. This event, in a sense, crowns all that has been said previously about Christ entrusting divine truths to women as well as men.

— John Paul II[272]

On June 10, 2016, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued a decree which elevated Mary's liturgical commemoration from an obligatory memorial to a feast day, like that of most of the Apostles (Peter and Paul are commemorated with a solemnity).[273] The Mass and Liturgy of the Hours (Divine Office) remained the same as they were, except that a specific preface was added to the Mass to refer to her explicitly as the "Apostle to the Apostles".[274]

Protestantism

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer had on July 22 a feast of Saint Mary Magdalene, with the same Scripture readings as in the Tridentine Mass and with a newly composed collect: "Merciful father geue us grace, that we neuer presume to synne through the example of anye creature, but if it shall chaunce vs at any tyme to offende thy dyuine maiestie: that then we maye truly repent, and lament the same, after the example of Mary Magdalene, and by lyuelye faythe obtayne remission of all oure sinnes: throughe the onely merites of thy sonne oure sauiour Christ." The 1552 edition omitted the feast of Saint Mary Magdalene, which was restored to the Book of Common Prayer only after some 400 years.[275]

Modern Protestants honor her as a disciple and friend of Jesus.[276] Anglican Christians refer to her as a saint and may follow her example of repentance;[277] While some interpret the Thirty-Nine Articles as forbidding them to call upon her for intercession,[278] other Anglicans, citing the Episcopal burial service, say they can ask the saint to pray for them.[279] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America honors Mary Magdalene on July 22 as an Apostle, albeit as a Lesser Festival.[280] Presbyterians honor her as the "apostle to the apostles"[281] and, in the book Methodist Theology, Kenneth Wilson describes her as, "in effect", one of the "first missionaries".[282]

Baháʼí Faith

There are many references to Mary Magdalene in the writings of the Baháʼí Faith, where she enjoys an exalted status as a heroine of faith and the "archetypal woman of all cycles".[283] `Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, said that she was "the channel of confirmation" to Jesus' disciples, a "heroine" who "re-established the faith of the apostles" and was "a light of nearness in his kingdom".[284] `Abdu'l-Bahá also wrote that "her reality is ever shining from the horizon of Christ", "her face is shining and beaming forth on the horizon of the universe forevermore" and that "her candle is, in the assemblage of the world, lighted till eternity".[285] `Abdu'l-Bahá considered her to be the supreme example of how women are completely equal with men in the sight of God and can at times even exceed men in holiness and greatness.[286] Indeed he said that she surpassed all the men of her time,[287] and that "crowns studded with the brilliant jewels of guidance" were upon her head.[288]

The Baháʼí writings also expand upon the scarce references to her life in the canonical Gospels, with a wide array of extra-canonical stories about her and sayings which are not recorded in any other extant historical sources. `Abdu'l-Bahá clasaidimed that Mary traveled to Rome and spoke before the Emperor Tiberius, which is presumably why Pilate was later recalled to Rome for his cruel treatment of the Jews (a tradition also attested to in the Eastern Orthodox Church).[289] Baháʼís have noted parallels between Mary Magdalene and the Babí heroine-poet Táhirih. The two are similar in many respects, with Mary Magdalene often being viewed as a Christian antecedent of the latter, while Táhirih in her own right could be described as the spiritual return of the Magdalene; especially given their common, shared attributes of "knowledge, steadfastness, courage, virtue and will power", in addition to their importance within the religious movements of Christianity and the Baháʼí Faith as female leaders.[290]

Relics

Many of the alleged relics of the saint are held in Catholic churches in France, especially at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, where her skull (see above) and the noli me tangere are on display; the latter being a piece of forehead flesh and skin said to be from the spot touched by Jesus at the post-resurrection encounter in the garden.[291][292] A tibia also kept at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume is the object of an annual procession.[292]

Her left hand relic is kept in the Simonopetra Monastery on Mount Athos.[293]

Speculations

In 1998, Ramon K. Jusino proposed an unprecedented argument that the "Beloved Disciple" of the Gospel of John is Mary Magdalene. Jusino based his argument largely on the Nag Hammadi Gnostic books, rejecting the view of Raymond E. Brown that these books were later developments, and maintaining instead that the extant Gospel of John is the result of modification of an earlier text that presented Mary Magdalene as the Beloved Disciple.[296] Richard J. Hooper does not make the Jusino thesis his own, but says: "Perhaps we should not altogether reject the possibility that some Johannine Christians considered Mary Magdalene to be 'the disciple whom Jesus loved'."[297] Esther A. de Boer likewise presents the idea as "one possibility among others", not as a definitive solution to the problem of the identity of the anonymous disciple.[298] There is a theological interpretation of Mary as the Magdala, The Elegant Tower and certain churches honor her as a heroine of the faith in their teachings.[299]

Dan Brown's 2003 bestselling mystery thriller novel The Da Vinci Code popularized a number of erroneous ideas about Mary Magdalene,[300][301] including that she was a member of the tribe of Benjamin, that she was Jesus's wife, that she was pregnant at the crucifixion, and that she gave birth to Jesus's child, who became the founder of a bloodline which survives to this very day.[302] There is absolutely no historical evidence, from the canonical or apocryphal gospels, other early Christian writings, or any other ancient sources, to support any of these statements.[302][303] The Da Vinci Code also purports that the figure of the "beloved disciple" to Jesus's right in Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is Mary Magdalene, disguised as one of the male disciples;[304] art historians maintain that the figure is, in reality, the apostle John, who only appears feminine due to Leonardo's characteristic fascination with blurring the lines between the sexes, a quality which is found in his other paintings, such as St. John the Baptist (painted c. 1513–1516).[305] Furthermore, according to Ross King, an expert on Italian art, Mary Magdalene's appearance at the last supper would not have been controversial and Leonardo would have had no motive to disguise her as one of the other disciples,[306] since she was widely venerated in her role as the "apostle to the apostles" and patron of the Dominican Order, for whom The Last Supper was painted.[306] There would have even been precedent for it, since the earlier Italian Renaissance painter Fra Angelico had included her in his painting of the Last Supper.[307] Numerous works were written in response to the historical inaccuracies in The Da Vinci Code,[308][309] but the novel still exerted massive influence on how members of the general public viewed Mary Magdalene.[310][303]

In 2012, scholar Karen L. King published the Gospel of Jesus' Wife, a purported Coptic papyrus fragment in which Jesus says: "My wife ... she will be able to be my disciple." The overwhelming consensus of scholars, including King herself, is that the fragment is a modern forgery.[311][312][313][314] If genuine, the papyrus would have dated to sometime between the sixth and ninth centuries. Although the fragment does not contain the name of Mary Magdalene, some authors speculated that she was the woman referred to.[315]

Ehrman states that the historical sources reveal absolutely nothing about Jesus's sexuality[316] and that there is no evidence whatsoever to support the idea that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married or that they had any kind of sexual or romantic relationship.[316] None of the canonical gospels imply such a thing[317] and, even in the late Gnostic gospels, where Mary is shown as Jesus's closest disciple,[317] the love between them is not sexual.[317] The extremely late Greater Questions of Mary, which is not extant, allegedly portrayed Mary not as Jesus's wife or partner, but rather as an unwilling voyeur.[128] Ehrman says that the Essenes, a contemporary Jewish sect who shared many views with Jesus, and the apostle Paul, Jesus's later follower, both lived in unmarried celibacy,[294] so it is not unreasonable to conclude that Jesus did as well.[294]

Furthermore, according to Mark 12:25, Jesus taught that marriage would not exist at all in the coming kingdom of God.[318] Since Jesus taught that people should live as though the kingdom had already arrived, this teaching implied a life of unmarried celibacy.[319] Ehrman says that, if Jesus had been married to Mary Magdalene, the authors of the gospels would definitely have mentioned it, since they mention all his other family members, including his mother Mary, his father Joseph, his four brothers, and his at least two sisters.[320] Casey rejects the idea of Mary Magdalene as Jesus's wife as nothing more than wild popular sensationalism.[295] Kripal writes that "the historical sources are simply too contradictory and simultaneously too silent" to make absolute declarations regarding Jesus' sexuality.[321]

Music

- Magdalena lugens voce sola cum symphonia, H.343 & H.343 a, motet for 1 voice, 2 treble instruments and continuo (1686–87).

- For Mary Magdalene, H.373, motet for 2 voices, 2 flutes and continuo (date unknown).

- Magdalena lugens, H.388, motet for 3 voices and continuo (date unknown).

- Dialogus inter Magdalena et Jesum 2 vocibus Canto e Alto cum organo, H.423, for 2 voices and continuo (date unknown).

Antonio Caldara Maddalena ai piedi di Cristo, oratorio (1700).

Jules Massenet, Marie-Magdeleine, oratorio in 3 acts (1873).

"Mary Magdelene" by Meshell Ndegeocello (1996)

See also

Notes

- /ˈmæɡdəlɪn, -iːn/; Hebrew: מרים המגדלית; original Biblical Greek: Μαρία ἡ Μαγδαληνή María hē Magdalēnē, literally "Mary the Magdalene",[1]

- In Hebrew Migdal (מגדל) means "tower", "fortress"; in Aramaic, "Magdala" means "tower" or "elevated, great, magnificent".[19] Interpreters since the time of Jerome have suggested that Mary was called Magdalene because of her stature and faith, i.e. because she was like a tower: "Mary Magdalene received the epithet 'fortified with towers' because of her earnestness and strength of faith, and was privileged to see the rising of Christ first even before the apostles" (letter of St. Jerome translated by Susan Haskin, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor, p. 406). Other interpreters have seen Magdalene as referring to a kind of hairstyle. This translation stems from certain passages in uncensored versions of the Talmud, where a woman, esoterically identified as Jesus's mother, is called "hamegadela se’ar nasha", which has been translated "Miriam, the dresser of women's hair", possibly a euphemism for "prostitute". See R.T. Herford, Christianity in Talmud and Midrash, pp. 40f. The Talmudic passages are at tractate Sanhedrin 67a and tractate Hagigah 4b of the Babylonian Talmud; cf. tractate Shabbat 104b. The English theologian John Lightfoot (1602–1675) noted these passages and commented: "Whence she was called Magdalene, doth not so plainly appear; whether from Magdala, a town on the lake of Gennesaret, or from the word which signifies a plaiting or curling of the hair, a thing usual with harlots." (Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, chapter "Exercitations upon the Gospel of St. Matthew".)[20]

- Mary Magdalene's name is mostly given as Μαρία (Maria), but in Matthew 28:1 as Μαριάμ (Mariam),[23][24] both of which are regarded as Greek forms of Miriam, the Hebrew name for Moses' sister. The name was extremely popular during the first century due to its connections to the ruling Hasmonean and Herodian dynasties.[25] In the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene is also referred to simply as "Mary" at least twice.[26]

- See, for instance, 1 Thessalonians 5:26, Romans 16:16, 1 Corinthians 16:20, 2 Corinthians 13:12, Mark 14:43–45, Matthew 26:47–50, Luke 22:48, and 1 Peter 5:14

References

- Μαρία η Μαγδαληνή in Matt 27:56; 27:61; 28:1; Mark 15:40; 15:47; 16:1; 16:9 replaces "η" with "τη" because of the case change. Luke 8:1 says "Μαρία ... η Μαγδαληνή" and 24:10 says "η Μαγδαληνή Μαρία". John 19:25, 20:1 and 20:18 all say "Μαρία η Μαγδαληνή".