Heliographic copier

A heliographic copier or heliographic duplicator[1] is an apparatus used in the world of reprography for making contact prints on paper from original drawings made with that purpose on tracing paper, parchment paper or any other transparent or translucent material using different procedures. In general terms some type of heliographic copier is used for making: Hectographic prints, Ferrogallic prints, Gel-lithographs or Silver halide prints. All of them, until a certain size, can be achieved using a contact printer with an appropriate lamp (ultraviolet, etc...) but for big engineering and architectural plans, the heliographic copiers used with the cyanotype and the diazotype technologies, are of the roller type, which makes them completely different from contact printers.

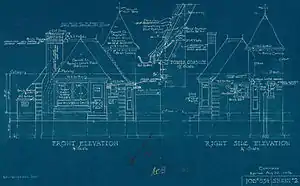

In the "argot" of engineers, architects and designers, the resulting plan copies coming from any type of heliographic copier no matter they were either blue or white, were traditionally called blueprints, name derived from the blue background color of the cyanotype technique, which was the previous process for obtaining blueprints, When the diazo based compounds changed the background color to white, in technical environments, -by tradition-, the name for copies of technical drawings remained Blueprint , although in English-speaking countries, it was intended, without much success, to change the name from Blueprint to Whiteprint. Depending on the color or the line and background, the appropriate paper may be developed for blueprints (blue background), whiteprints (blue line and white background), black line (white background) and sepia, using the same machine and process.

Using the right compound some "cyano copiers" could be adapted to be used as "diazo copiers".[2]

History

The light sensitivity of certain chemicals used in the cyanotype process, was already known when the English scientist and astronomer Sir John Herschel discovered the procedure in 1842 and several other related printing processes were patented by the 1890s .[3] When Herschel developed the process, he considered it mainly as a means of reproducing notes and diagrams, as its use in blueprints.[4]

Cyano copier

This is a simple process for the reproduction of any light transmitting document. Engineers and architects used to draw their designs on cartridge paper; these were then traced by hand on to tracing paper using Indian ink, which were kept to be reproduced with the cyano-copier whenever they were needed.

Introduction of the blueprint process eliminated the high expenses of photolithographic reproduction or of hand-tracing of original drawings. By the latter 1890s in American architectural offices, a blueprint was one-tenth the cost of a hand-traced reproduction.[5] The blueprint process is still used for special artistic and photographic effects, on paper and fabrics.[6]

Features

Different blueprint processes based on photosensitive ferric compounds have been used. The best known is probably a process using ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide.[7] In this procedure a distinctly blue compound is formed and the process is also known as cyanotype. The paper is impregnated with a solution of ammonium ferric citrate and dried. When the paper is illuminated a photoreaction turns the trivalent (ferric) iron into divalent (ferrous) iron. The image is then developed using a solution of potassium ferricyanide forming insoluble ferroferricyanide (Turnbull's blue identical to Prussian blue) with the divalent iron. Excess ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide are then washed away.

Diazo copier

The process of diazotype (Whiteprints) replaced the cyanotype process (blueprints) for reproducing architectural and engineering drawings because the process was simpler and involved fewer toxic chemicals.[8]

A blue-line print is not permanent and will fade if exposed to light for weeks or months, but a drawing print that lasts only a few months is sufficient for many purposes (test prints)

The different names blue-line copier, whiteprint copier or diazo copier,[9] were given, due to the nature of the process, which consists in exposing to an ultraviolet light a previously sensitized paper with a component called diazo, and finally developing it in a bath (a solution of ammonia in water) which converts the parts not exposed to light, to a dark blue colour (blue-line) over an almost white background.

Features

A little smell of ammonia and a faintly purplish paper colour are the main characteristics of a whiteprint. The dark lines in the original are converted to a dark violet colour, while the white parts degrade to a light purplish colour. The back of the drawings is a cream colour in which the folds are degraded to a lighter colour.

The diazo copies are of different sizes and for this reason the diazo paper is obtainable in standard sizes that vary from 30 cm to 60 cm wide, after de process the copied paper can be cut to the desired size.

The paper used for the diazo copies is usually a bond paper or similar type, with a diazo coating sensitive to the UV light.

Operation

The original plan and the sensitized paper , are introduced, in perfect contact, within the copier rollers that pull and expose them to a source of ultraviolet light, typically a blacklight lamp, similar to the manual action to expose both sheets strongly bonded directly to the sunlight, and once exposed:

- In the cyano copier, the copied paper is immersed in a developer solution made from potassium ferricyanide and it must be washed with water to eliminate the excess ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide.

- In the diazo copier, the paper is immersed in a developer solution made from ammonia (or ammonia vapor) converting the parts of the paper not exposed to the light source to a characteristic dark blue colour .

See also

References

- League of Nations (1937). Economic Committee: Sub-committee of Experts for the Unification of Customs Tariff Nomenclature. Draft Customs Nomenclature.

- David L. Taylor (2004). Blueprint Reading for MachineTrades. Cengage Learning. pp. 3 –. ISBN 1-4018-9998-6.

- "Exploring Photography – Photographic Processes – Cyanotype". V&A. 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- "The Cyanotype". Vernacular Photography. 2012-12-12. Archived from the original on 2013-03-30. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- Mary N. Woods From Craft to Profession: The Practice of Architecture in Nineteenth-Century America University of California Press, 1999 ISBN 0520214943, page 239-240

- Gary Fabbri, Malin Fabbri Blueprint to Cyanotypes - Exploring a Historical Alternative Photographic ProcessLulu.com, 2006 ISBN 141169838X page 7

- Blue, WS: PSLC.

- Eva Zeisel; Robert Sabella (2006). Blueprints replaced by whiteprints. Que Certification. pp. 244–. ISBN 978-0-7897-3504-1.

- FJM Wijnekus; E.F.P.H. Wijnekus (22 October 2013). Dictionary of the Printing and Allied Industries: In Inglés (with definitions), French, German, Dutch, Spanish andItalian. Elsevier Science. pp. 844 –. ISBN 978-1-4832-8984-7.

Bibliography

- Blacklow, Laura. (2000) New Dimensions in Photo Processes: a step by step manual. 3rd ed.

- Ware, M. (1999) Cyanotype: the history, science and art of photographic printing in Prussian blue. Science Museum, UK

- María de los Santos García Felguera; Marie-Loup Sougez; Helena Pérez Gallardo; Carmelo Vega (2007). Historia general de la fotografía. Cátedra. ISBN 978-84-376-2344-3.