Henry Charles Lea

Henry Charles Lea (September 19, 1825 – October 24, 1909) was an American historian, civic reformer, and political activist. Lea was born and lived in Philadelphia.

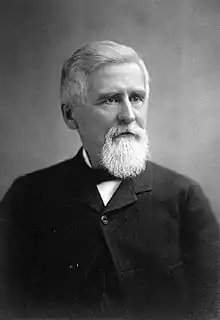

Henry Charles Lea | |

|---|---|

Lea c. 1870 | |

| Born | November 19, 1825 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | October 24, 1909 (aged 83) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Caroline Jaudon

(m. 1850) |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Mathew Carey Lea (brother) |

Early and family life

Parents

His father, Isaac Lea (1792–1886) was a distinguished naturalist and member of the American Philosophical Society, and publisher. Isaac Lea was descended from a Philadelphia Quaker family, and had been born in Wilmington, Delaware. On March 8, 1821, Isaac married Frances Anne Carey (1799–1873), daughter of Mathew Carey, the Philadelphia publisher whose business he ultimately took over. Mathew Carey, born in Ireland in 1760, came to the United States in 1784, escaping prosecution by the British government for his outspoken criticism of Britain's Irish policy. During a period of exile in Paris, Carey had met Benjamin Franklin, for whose print shop he worked. Carey and Isaac Lea's highly successful publishing house printed the works of Thomas Jefferson, Parson Weems, Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, and the first quarto Bible of American manufacture (both the Douay version and the Authorized version).

Education

Irish American theoretical mathematician Eugenius Nulty tutored both Henry Charles Lea and his elder brother the later, pioneer photographic chemist Mathew Carey Lea (called by family “Carey”) at their home in Philadelphia.[1] Nulty not only helped mold Henry Charles Lea as a scholar but also (along with his father's and grandfather's connections) opened many an academic door for Lea.

The erudite Nulty gave the Lea brothers a classical education. He singlehandedly taught the pair the entirety of the trivium (grammar, logic and rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music and celestial navigation) and classical languages and history of its standard curriculum. Nulty immersed the boys in a single subject for long periods to encourage its complete mastery. Observing Henry's precocity, Nulty early on encouraged him to master far more difficult lessons than usually expected of a student his age. Henry Lea also demonstrated a facility for languages and analytical thought.[2][3]

During their years under Nulty's tutelage, Henry and Carey also worked in the Booth & Boy chemical laboratory. This led to Henry's first published paper—at age 13—about manganese salts.[4] The avocational interests of Lea's father (a noted natural scientist and conchologist as well as publisher) and Lea's mother (a knowledgeable botanist and classical linguist as well as homemaker) supplemented Henry's and Carey's education and shaped their interests. Henry also followed his father's interest in natural history and wrote several papers on descriptive conchology. He also displayed drawing talent and illustrated his own early articles about fossil shells that he had collected. His drawings were also used for the engravings illustrating his father's revision of the Synopsis of the Naiades in 1838. Henry Charles Lea developed an interest in poetry and at his mother's suggestion, translated Greek poets and composed original verse. Later, he often wrote satirical parodies of popular songs about politics.

Marriage

On 27 May 1850, Henry Charles Lea married his first cousin and orphan Anna Caroline Jaudon (1824–1912). Her father, merchant William Latta Jaubon (1798–1832) of Bucks County, Pennsylvania had died in Cincinnati, Ohio when she was a child, followed four years later by her mother, Susan Gibson Lea Jaudon (1799–1836). The Jaudons were a wealthy Huguenot family from Soubise, France, and after the Edict of Nantes Peter Jaudon emigrated to Bucks County (and his family became Presbyterians), and Elie Jaudon emigrated to South Carolina. Perhaps the most noteworthy members were the teacher Daniel Jaudon (1767–1826, Anna Caroline's grandfather) and the financier Samuel Jaudon. Two years later Lea's brother Matthew Carey Lea married her sister Elizabeth (1827–1881), whose husband merchant William Bakewell had died in Cincinnati in 1850, leaving her with a young daughter.[5] The Leas had three sons (who succeeded their father in the publishing business) and a daughter: Francis Henry Lea (1851–1902), Charles Matthew (1853–1886), Anna (Nina) Lea (1855–1927) and Arthur Henry Lea (1859–1939).

Career

In 1843 Henry Charles Lea joined his father in business and continued with the firm (renamed Lea, Brothers & Co. and even later Lea & Febinger) until 1880 when his sons took over the business.

In 1847, after working in the family publishing firm for four years, Lea suffered a nervous breakdown and the twenty-two-year-old abandoned his intellectual and scientific work for some time. Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, one of the country's most prominent doctors in the field of nervous disorders, treated Lea and became a family friend. During his convalescence, Lea began reading French memoirs of the medieval period. They kindled his interest in medieval history and changed his career course from scientist to historian.

Historian

Thereafter Lea focused on history, mainly on church history in the later Middle Ages, and on institutional, legal, and ecclesiastical history, as well as magic and witchcraft. He also did significant work on the history of the Italian city-states. His active writing career on historical subjects spanned more than fifty years, during which Lea published ten books and numerous articles. His literary reputation rests largely on those books. Highly disciplined work habits (and the ability to purchase manuscripts in Europe and Latin America and have them shipped to Philadelphia) led Lea to continue writing despite even headaches and eye problems. His productivity increased during his final twenty-five years after he retired as a publisher and built an extension to his house at 2000 Walnut Street, for his extensive manuscript collection.

Lea became an authority on the Spanish Inquisition, and his multi-volume work was considered groundbreaking, though opinionated. Although some criticized him for anti-Catholic bias,[6] Lea received honorary degrees from universities including Harvard, Princeton, Pennsylvania in the United States, as well as the Giessen and Moscow. His study of the Inquisition was also criticized for anti-Spanish bias, which Julián Juderías in 1914 termed the 'leyenda negra' (a/k/a Black legend).

Lea became a member of the newly formed American Historical Association in 1884, contributed several articles to its American Historical Review, and was elected its president in 1903. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1888.[7] When the second annual meeting of the newly formed American Folklore Society was held in Philadelphia in 1889, Lea met with some of the founders, sent an article for publication in the Society's journal, and became the first life-member of the organization.

Civic activist

During the American Civil War Lea was a member of the Union League of Philadelphia and headed its publication committee, writing many of the League's published pamphlets. In 1863 Lea was appointed one of the Bounty Commissioners under the Enrollment Act and served until 1865, working closely with Provost Marshal General James B. Fry accounting for the city's quotas of enlisted men. He thus he became involved with recruiting African American regiments to fight in the Union army.

Outspoken about public works and health projects in Philadelphia, Lea founded the public hygiene program at the University of Pennsylvania. He strongly opposed the building of City Hall at the Penn Square location at the intersection of Broad Street and Market Street (then known as High Street) where it now stands, preferring instead that it be built in Washington Square, near Independence Hall. Lea believed that the project cost too much, and was angered by the political corruption involved in the awarding of contracts and purchase of building materials. Lea planned and held a large public meeting to recruit support for his alternative to the Penn Square project.

The National Republican League chose Lea as its president in 1880 (the year he retired from his publishing business) and five years later, Lea served as president of the Association of Republicans and Independents. In 1891 he helped found "The Reform Political League of Pennsylvania", with Herbert Welsh as president, himself and Justus C. Strawbridge as vice-presidents, and Charles E. Richardson as secretary.

Lea joined with others in 1884 and filed a lawsuit to oppose building a large slaughterhouse on the Schuylkill River at Thirtieth and Spruce streets on land owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, citing the pollution of the river, the stench, and devaluation of properties near the plant. He also opposed the construction of the Market Street elevated train, over properties he owned on Market Street, as well as building the "boulevard" from City Hall northwest to Fairmount Park, where the Philadelphia Museum of Art was later built.

Death and legacy

Lea died in Philadelphia and was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery.[8]

His children ultimately conveyed his collection of purchased manuscripts and incunabula as well as other early printed books to the University of Pennsylvania. In 1925, the University dedicated a library, which it named in his honor and which includes much of that personal collection of books and manuscripts. Speakers at the dedication included Professor George Lincoln Burr of Cornell University, who worked to complete the manuscript of Lea's Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft ; Professor Dana C. Munro of Princeton University, vice president of the American Historical Association, who had used Lea's collections as a young scholar; and Hampton L. Carson, Philadelphia historian and former attorney general of Pennsylvania.

Works

- Superstition and Force: Essays on the Wager of Law, the Wager of Battle, the Ordeal, Torture Henry C. Lea, 1866.

- Historical Sketch of Sacerdotal Celibacy, J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1867.

- Studies in Church History. The Rise of the Temporal Power - Benefit of clergy - Excommunication, Henry C. Lea, 1869.

- Translations and Other Rhymes, Privately Printed, 1882.

- A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, The Macmillan Company, 1906 [1st Pub. New York, Harper & Brothers, 1887].

- Chapters from the Religious History of Spain Connected with the Inquisition, Lea Brothers & Co., 1890.

- A Formulary of the Papal Penitentiary in the 17th Century, Lea Brothers & Co., 1892.

- The Absolution Formula of the Templars, The Knickerbocker Press, 1893.

- A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences in the Latin Church, Volume II, Volume III, Lea Brothers & Co., 1896.

- The Indian Policy of Spain, n.p., 1899.

- The Dead Hand; a Brief Sketch of the Relations between Church and State with Regard to Ecclesiastical Property and the Religious Orders, William J. Dornan, 1900.

- The Moriscos of Spain; their Conversion and Expulsion, Lea Brothers & Co., 1901.

- Léo Taxil, Diana Vaughan et l'Église Romaine: Histoire d'une mystification, Paris, France: Sociéte Nouvelle de Librairie et d'édition, 1901.

- Ethical Values in History, n.p., 1904.

- A History of the Inquisition of Spain, Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV, 1906–1907.

- The Inquisition in the Spanish Dependencies, The Macmillan Company, 1922 [1st Pub. 1908].

- Memoir, Privately printed, 1910.

- Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1939.

References

- The Biographical Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania of the Nineteenth Century Philadelphia: Galaxy Publishing Company (1874)

- Edward Sculley Bradley Henry Charles Lea. A Biography Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1931) p 42

- Edward Peters “Henry Charles Lea and the Libraries within a Library” 2 from the Penn Library Collections at 250, page 35.”

- "Henry Charles Lea Papers - Biographical Sketch". Penn Special Collections. University of Pennsylvania:Rare Book & Manuscript Library. 2003-01-31. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- Edwin Jaquett Seller, The Jaubon family of Pennsylvania, (Allen, Lane & Scott, Philadelphia, 1924) p. 19 available at from Bucks County, Pennsylvania https://books.google.com/books?id=l6HRAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=jaudon+philadelphia&source=bl&ots=48BIOA6Igf&sig=9r0coBVYHpCm7C673qAB-ANDwtE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=AnoFVeHxI4iYgwTZ34OACA&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=jaudon%20philadelphia&f=false, also available at Hathi Trust

- Dewey, R. S. "The Last Historian of the Inquisition," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XIII, N°. 51, July 1888.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- "Henry Charles Lea". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lea, Henry Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 314.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lea, Henry Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 314.

Other resources

- Henry Charles Lea papers, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

- Henry Charles Lea research collection on the Inquisition, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

- Henry Charles Lea Library at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania

Further reading

- Baumgarten, Paul Maria (1909). Henry Charles Lea's Historical Writings: A Critical Inquiry Into Their Method and Merit. New York: J.F. Wagner.

- Bouquillon, Thomas (1891). "Henry C. Lea as a Historian," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XVI, pp. 131–158.

- Bradley, Edward Sculley (1931). Henry Charles Lea. A Biography, University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bussy, R. Kenneth (1985). Two Hundred Years of Publishing: A History of the Oldest Publishing Company in the United States, Lea & Febiger 1785–1985. Lea & Febiger.

- Cheyney, Edward Potts (1911). "On the Life and Works of Henry Charles Lea," Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Coulton, G.G. (1937). Sectarian History. Barnicotts.

- O'Brien, John M. (1967). "Henry Charles Lea: The Historian as Reformer," American Quarterly, Vol. XIX, No. 1, pp. 104–113.

- Peters, Edward (1987). "Henry Charles Lea and the `Abode of Monsters'." In: The Spanish Inquisition and the Inquisitorial Mind, edited by Angel Alcal, Atlantic Research Publications.

- Tollebeek, Jo (2004). Writing the Inquisition in Europe and America: The Correspondence Between Henry Charles Lea and Paul Fredericq. Palais des Académies.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Charles Lea. |

- Works by Henry Charles Lea at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Charles Lea at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Charles Lea at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Biographical Sketch from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania

- Lea, Henry Charles from The Columbia Encyclopedia

- Henry Charles Lea at Find a Grave