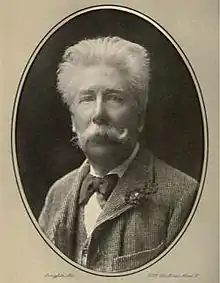

Henry Lucy

Sir Henry William Lucy JP, (5 December 1842 – 20 February 1924) was one of the most famous English political journalists of the Victorian era. He was acknowledged as the first great lobby correspondent. Lucy wrote articles for Punch, Strand Magazine, The Observer, The New York Times and many others. He also wrote books detailing the workings of the Houses of Parliament and two autobiographies. He was Knighted in 1909. Lucy was widely known in the United Kingdom and in North America. President Woodrow Wilson said his articles in The Gentleman's Magazine inspired his mind and propelled him into public life. Lucy was a serious commentator of parliamentary affairs, but also an accomplished humourist and a parliamentary sketch-writer. His friend, the explorer Ernest Shackleton, named a mountain in Antarctica after him.

.jpg.webp)

Life and career

Henry Lucy was born in Crosby, near Liverpool in 1842,[lower-alpha 1][1] the son of Robert Lucy, a rose-engine turner in the watch trade, and his wife, Margaret Ellen Kemp. He was baptised, William Henry on 23 April 1843 at St. Michael's Church, Crosby. While he was still an infant the family removed to Everton, Liverpool, where he attended the private Crescent School until August 1856; thereafter until 1864 he was junior clerk to Robert Smith, hide merchant, of Redcross Street, Liverpool.

While working as a clerk he had poetry published in the Liverpool Mercury; taught himself shorthand. Worked for the Shrewsbury Chronicle as chief reporter from 1864,[2] and for Shrewsbury's local Observer, and the Shropshire News. Before giving notice to the Chronicle he wrote leader articles for the other Shrewsbury papers, which mostly replied to his own leaders in the Chronicle the week before, besides writing "penny-a-liners" of Shropshire news for London newspapers.[3]

Lucy married on 29 October 1873 Emily Anne (1847–1937), daughter of his old schoolmaster at Liverpool, John White. There were no children of the marriage.

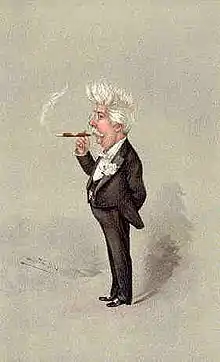

Lucy lived in Paris during 1869 and learned French. After returning to England he wrote for Pall Mall Gazette from 1870 and as parliamentary reporter for Daily News from 1873. He stayed with the Liberal newspaper, for which he was promoted the editor. He was a parliamentary sketch writer for Punch from 1881.[4] He used the pseudonym "Toby, M.P." from 1881 to 1916. He wrote the weekly column "The Essence of Parliament" in Punch magazine for 35 years. When not writing under one of his pseudonyms, he was usually styled Henry W. Lucy.

In 1880, Lucy began writing for The Observer the Cross Bench column. This he continued to do for 29 years.

Lucy's lasting memorial is in the volumes he compiled from his Punch parliamentary sketches: A Diary of Two Parliaments (2 vols., 1885–1886), A Diary of the Salisbury Parliament, 1886–1892 (1892), A Diary of the Home Rule Parliament, 1892–1895 (1896), A Diary of the Unionist Parliament, 1895–1900 (1901), and The Balfourian Parliament, 1900–1905 (1906). They amount to a history of the Commons in its heyday and have been extensively mined by historians.

Lucy was a long-running friend and fund-raiser for Shackleton's expeditions to the South Pole. His generosity exceeded Shackleton's expectations, guaranteeing their success. Knighted in 1909, he was the first lobby correspondent to be seen as a social equal of the politicians in the Commons on whom he reported. He rose to national prominence during the constitutional crises of 1909–1910, during which he revealed to the Commons that Navy estimates had been as much as £60 million all along. His article was used as evidence by Hugh Foster MP to demand clarity from the government on the budgetary proposals being blocked in the Lords.[5]

His London home was at 42 Ashley Gardens, and he was a member of the National Liberal Club.

Sir Henry Lucy left a huge sum of money, over £250,000,[6] and was probably the wealthiest Victorian journalist who was not also a newspaper proprietor. In his will he endowed a "Sir William Henry Lucy Bed" at Shrewsbury's Royal Salop Infirmary "in memory of his pleasant connection with Shrewsbury" as a journalist.[7] A pioneer of the profession of public affairs consultancy, Lucy had already been awarded a knighthood, when invited to Buckingham Palace by Queen Mary, to whom he presented a gift of his political anecdote collection.[8]

Sir Henry Lucy died of bronchitis at Whitethorn, his country house at Hythe, Kent in 1924, aged 81. (The house is now known as "Lucys" on Lucys Hill).[1] In 1935, his widow Lady Lucy donated £1,000 to found the Sir Henry Lucy Scholarship at Merchant Taylors' School, Crosby. There are several portraits of Sir Henry Lucy at the National Portrait Gallery, including one by John Singer Sargent.

The mixed perceptions of his personality have been left to modern biographers to examine more deeply.[9]

Quotes about him

US President Woodrow Wilson credited Lucy with propelling him into public life,[10] describing his articles in The Gentleman's Magazine as "the deciding impulse of [my] life; vivid descriptions of Parliament, which took an enthralling hold on [my] young imagination" (New York Times, 1912).[11]

"Never in the House, but always of it, Lucy seemed to occupy for a long time a position of his own, as a species of familiar spirit or licensed jester, without which no Parliament was complete." Times Obit., 1924[12]

The journalist and writer Frank Harris said of Lucy: "He met everyone, and knew no-one."[13]

Mount Henry Lucy (3,020 m) in Antarctica was named after him by Shackleton in 1909,[14] as thanks for Lucy's help in publicising his Nimrod Expedition and raising funds.

"Shackleton's naming an Antarctic mountain after Sir Henry Lucy amuses me. I knew Lucy very well – a little toadie, who afterwards toadied himself into a title..." Ambrose Bierce, letter, 1910 [15]

Works

Articles

Lucy wrote many articles for Punch, Strand Magazine, Harper's Magazine, Cornhill Magazine, The New York Times and others. Some of these are noted below.

- "Mr. Gladstone at Hawarden" (1882) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "Glimpses Of Great Britons" (1882) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "Hatfield House and the Marquess of Salisbury" (1885) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "Men of the Salisbury Parliament" (1891) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "Electioneering methods in England" (1892) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "The Power of the British Press" (1896) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "The Queen's Parliaments, Part I" (1897) Online version at Cornell University Library

- "The Queen's Parliaments, Part II" (1897) Online version at Cornell University Library

Autobiographies

Lucy wrote two autobiographies, each in three volumes:

Sixty Years in the Wilderness

- Volume I "Some passages by the way" (1909) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Volume II "More passages by the way" (1912) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Volume III "Nearing Jordan" (1916) Online version at The Internet Archive

The Diary of a Journalist

- Volume I (1920) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Volume II "Later Entries" (1922) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Volume III "Fresh Extracts" (1923)

Pseudonyms

On occasion Lucy used one of the following pseudonyms for his works.

- Toby, M.P.

- The Member for the Chiltern Hundreds

- The Member for Barks

- Baron de Book-Worms

Books

Lucy wrote a number of books:

- Gideon Fleyce [novel] (1883) Online version at The Internet Archive

- East by West: a journey in the Recess (1885) Online version at The Internet Archive

- A Diary Of Two Parliaments: The Disraeli Parliament, 1874-1880 (1885) Online version at The Internet Archive

- A Diary Of Two Parliaments: The Gladstone Parliament, 1880-1885 (1886) Online version at The Internet Archive

- A Popular Handbook of Parliamentary Procedure (1886) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Faces and Places (1892) Online version at Project Gutenberg

- A Diary of the Salisbury Parliament, 1886-1892 (1892) Online version at The Internet Archive

- The Right Honourable W. E. Gladstone: A Study from Life (1895) Online version at The Internet Archive

- A Diary of the Home Rule Parliament, 1892-1895 (1896) Online version at The Internet Archive

- The Log of the Tantallon Castle (1896)[16]

- The Miller's Niece, and some distant connections [short stories] (1896)

- The Law and Practice of General Elections: A Popular Handbook (1900)

- A Diary of the Unionist Parliament, 1895-1900 (1901) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Peeps at Parliament, taken from behind the Speaker's Chair (1904) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Later peeps at Parliament, taken from behind the Speaker's Chair" (1905) Online version at The Internet Archive

- The Balfourian Parliament, 1900-1905" (1906) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Memories of Eight Parliaments (1908) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Men and Manner in Parliament (1919) Online version at The Internet Archive

- Lords and Commoners (1921) Online version at The Internet Archive

Quotes

Lucy's analytical observations of the Conservative antagonist were characteristic:

The physical energy with which this election speech was delivered was certainly very remarkable for a man in his seventy-fourth year. There is, however, unmistakeable evidence of pumping up in the Premier's (Beaconsfield's) latest oratorical feats. The vigour is spasmodic, the strength artificial, and the listener has a feeling that at any moment a spring may break, a screw go loose, and the whole machinery come to a sudden stop.

Remarking on the Liberal counterpart's performance in the Chamber, he sensed that

Gladstone's tours de force are perfectly natural. When after one of his great speeches he resumes his seat, he is, and often proves himself to be, ready to start again. With the Premier, the excitement of the moment over and the appointed task achieved, he falls into a state of prostration painful to witness. His eyes seem to lose all expression, his cheeks fall in, and his face takes on a ghastly hue. Physically he is at least ten years older than Gladstone.[17]

The House of Commons is unique in many ways. I believe the main foundation of the position it holds among the parliaments of the world is the condition of volunteered unremunerated service. In spite of the sneers from disappointed or flippant persons, a seat in the House of Commons remains one of the highest prizes of citizen life. There is no reason why any constituency desiring to do so may not return a member on the terms of paying him a salary. It is done in several cases, in two at least with the happiest results. It would be a different thing to throw the whole place open with standing advertisement for eligible Members at a salary. The horde of impecunious babblers and busybodies attracted by such a bait would trample down the class of man who compose the present House of Commons and who are, in various ways, in touch with all the multiform interests of the nation. Strand Magazine, 1893 [18]

"I would rather have been editor of Punch, than Emperor of India..."[19]

"Yesterday Herbert Spencer died at Brighton. His natural temperament was such that many things that other men got along with placidly gave him acute pain. To put the incontestable fact another way, he was perhaps the most irascible man who has ever been faced by the inconvenience of other people presuming to inhabit the same globe"[20]

Notes

- Most early references give 5 December 1845 as the birthdate, as did Lucy himself. DNB cites a baptism in April 1843 and gives a putative birthdate of March 1843. English civil registration records the birth in the first quarter of 1843, as William Henry Lucy. Thus 5 December 1842 seems the most likely date of birth.

References

- [District:West Derby Vol:XX Page:863]

- Rachel Matthews (18 May 2017). The History of the Provincial Press in England. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-4411-5646-4. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Through Nine Reigns, 200 years of The Shrewsbury Chronicle. p. 52.

- "LUCY, Henry W." Who's Who. Vol. vol. 9. 1907. pp. 1090–1091.

- FINANCE BUSINESS (PROCEDURE).HC Deb 21 March 1910 vol 15 cc777-839

- probate, 14 April 1925, £263,672 1s. 5d., CGPLA Eng. & Wales

- Keeling-Roberts, Margaret (1981). In Retrospect, A Short History of The Royal Salop Infirmary. North Shropshire Printing Company. p. xvi. ISBN 0-9507849-0-7.From list of beds and cots endowed "in perpetuity".

- https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/1171553/diary-of-a-journalist

- A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce, Ambrose Bierce, S. T. Joshi, Tryambak Sunand Joshi, David E. Schultz.

- Woodrow Wilson and the Lost World of the Oratorical Statesman by Robert Alexander Kraig, 2004

- Governor Woodrow Wilson as his biographer knows him - New York Times article, 28 July 1912

See also the dedication and letter in Men and Manner in Parliament (1919), and Chapter 1 "The Orator", which first appeared pseudonymously in The Gentleman's Magazine in 1874. - Times Obituary (22 February 1924), p. 17.

- My Life and Loves by Frank Harris, Vol. 2, Chapter XXII.

- MapPlanet

- A Much Misunderstood Man – Selected letters of Ambrose Bierce edited by S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz.

- Weblog description of the book

- A Diary of Two Parliaments London, Cassell, 1885 p. 151

- YourMoneyDownTheDrain blog quotation from the Daily Mail, 16 January 2007

- Quoted in Writers, Readers and Reputations by Philip Waller, p. 78.

- quoted in On the Up and Up by Bruce Barton (reprinted Kessinger, 2004) p.154

External links

- Works by Henry Lucy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Lucy at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Lucy at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Mark Twain makes some parting remarks - New York Times article, 25 October 1903

- Sensation in the Lords witnessed by Toby, M.P. - New York Times article, 29 May 1904

- Toby, M.P. tells how late dinners worry the Government - New York Times article, 17 July 1904

- The Parliamentary Game - Review of Memories of Eight Parliaments, New York Times article, 16 May 1908

- To build 8 Dreadnoughts – New York Times article, 4 April 1909

- 'Toby, M.P.', Pinero and Tree knighted – New York Times article, 25 June 1909

- Sixty Years in the Wilderness – Review of Sixty years in the Wilderness, Vol. 1, New York Times article, 26 June 1909

- Humor in the House of Commons, by Toby, M.P. – New York Times article, 27 November 1910

- Toby, M.P. writes of the English Peerage – New York Times article, 25 December 1910

- Governor Woodrow Wilson as his biographer knows him – New York Times article, 28 July 1912

- Toby, M.P. – Review of Sixty years in the Wilderness, Vol. 2, New York Times article, 23 March 1913

- Washington ghost disclosed by Lucy – New York Times article, 25 July 1912

- A Humorist writes History – Review of The Diary of a Journalist, New York Times article, 9 January 1921

- Men and Manners in Parliament – Review of Men and Manner in Parliament, New York Times article, 24 July 1921

- Sir Toby, M.P. sketches Parliament – Review of Lords and Commoners, New York Times article, 25 June 1922

- Later Diary of Toby, M.P. – Review of The Diary of a Journalist: Later Entries, New York Times article, 10 September 1922

- Sir William Harcourt, Victorian Statesman – Book review by Sir Henry Lucy, New York Times article, 29 October 1922

- Death notice – notice of death in TIME Magazine, 3 March 1924

- Portraits of Sir Henry Lucy – Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Lucy. |