History of Pocklington

The town of Pocklington in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England has a recorded written history that goes back around 1,500 years, and archaeological evidence shows settlement at the site as long as 2,500 years ago. This gives it a longer history of settlement than larger contemporary settlements in the region and country such as York and even London. During this time, it has experienced plague, several invasions, the loss of its railway, and its marginalisation to a backwater under the Romans. Nevertheless, Pocklington has prospered where other market towns have failed. It has always been the commercial and civic centre for the district and was at one point the second largest settlement in Yorkshire.[1] It is the focal point of an area which has seen significant events through the centuries, many influencing English history.

Pocklington gets its name via the Old English "Poclintun" from the Anglian settlement of Pocel's (or Pocela's) people and the Old English word "tun" meaning farm or settlement [A D Mills, The Popular Dictionary of English Place-Names], but though the town's name can only be traced back to around 650 AD, the inhabitation of Pocklington as a site is thought to extend back a further 1000 years or more to the Bronze Age.

Historical timeline

Bronze Age Pocklington

It is not known exactly when there was first a settlement at Pocklington – archaeologists have found Iron Age remains in and around the town and many Bronze Age burials and other finds have been discovered in the neighbourhood. More recently in 2016 builders uncovered an earlier, Bronze Age, settlement, dating to around 800 BC.[2]

In 1937, wooden planks belonging to an ancient boat were discovered by a local man in nearby Ferriby. Originally estimated to date from 1300 BC, newer estimates using radiocarbon dating have placed the boats between the years 1890 BC to 1700 BC.

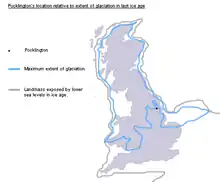

Certainly the Wolds area as a whole was a very attractive location for settlements to ancient man, who preferred to stay clear of the poorly drained and often flooded neighbouring vales – before the draining of a lot of land in the medieval era the flat land to the west and south of Pocklington was very marshy.

Archaeologists have experienced problems in recovering early remains and artefacts from the area intact because of the damage and disruption caused by centuries of arable land use – one skeleton discovered in 2005 was intact apart from its skull, which had been sheared off and crushed by a plough.[3]

Iron Age Pocklington

Ptolemy relates that the Parisii, an ancient Briton tribe (with branches in France, and after which Paris itself is named) inhabited a large part of what is now the East Riding of Yorkshire in the late Iron Age (50 BC) [Ptolemy, Geography]. They were probably displaced to Britain by population movements on the continent. It is possible that Pocklington was settled by the Parisii as early as the 5th century BC, but certainly by the time the Parisii participated in the general rising of Vercingetorix against Julius Caesar in 52 BC there is strong evidence that their regional capital was based at Pocklington itself.

In 2017, a Celtic warrior's grave, dated to about BC 320 to 174, was discovered at a housing development under construction in Pocklington at the Yorkshire Wolds. After archeologists had completed a very long excavation project, the site was found to include a bronze shield, remains of a chariot and the skeletons of ponies. The shield's boss bears a resemblance to the Wandsworth shield boss (circa BC 350 to 150), owned by the British Museum. One design element on the extremely-well preserved Pocklington shield, a scalloped border, "is not comparable to any other Iron Age finds across Europe, adding to its valuable uniqueness", said Paula Ware, managing director at MAP Archaeological Practice Ltd in late 2019.[4][5] Horses were rarely included in Iron Age burials, making the find particularly significant. "The discoveries are set to widen our understanding of the Arras (Middle Iron Age) culture and the dating of artefacts to secure contexts is exceptional," according to Paula Ware.[6]

Romano-British Pocklington

It is during the era of the Roman occupation that Pocklington suffered something of a reversal in its development. It was eclipsed by York as the prominent settlement within the Yorkshire region, with the City of York effectively beginning its life during this era and swiftly eclipsing Pocklignton in size and importance. Despite Pocklington's existing status and size at the time, York was favoured as the site of the Roman city Eboracum in around 71 AD. It is thought to have been selected, whilst Pocklington was ignored, because of its better water access (River Ouse, accessible via Humber estuary) and because it was a naturally crossing point on a plain of routes from all directions.

Despite Ermine Street (the primary Roman arterial road north from London) running close by Pocklington, the town was not garrisoned by Roman forces. A legionary barracks and important Roman town were constructed in York, which was for several years the home of the Roman Imperial Court and effectively the centre of administration for the Roman Empire, but Pocklington likely remained a Roman-influenced but little altered Iron Age settlement. There is archaeological evidence for some signs of Romanization (cultural) in Pocklington, including a Roman-style bath-house.[7]

The Roman name for Pocklington is not known but it is thought that Pocklington might be the presently unlocated Delgovicia, meaning "out of the way place" or, literally, backwater. However, Millington and Malton are competing candidates for this place-name also. By the time Ptolemy wrote his Geography in approximately 140 AD, he made no mention of Pocklington but instead referred to the capital of the Romano-British Parisi as being located in Petuaria, near modern-day Brough. Given that the Parisi themselves were non-literate and Ptolemy was writing at some remove, it is difficult now to know whether their capital shifted from Pocklington to Brough, or whether it was always at Pocklington, or always at Brough.

Around this time, the Roman authorities raised an irregular auxiliary unit from the area, known as the Company of Newcomers [Collingwood & Wright, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain].

There is also evidence of a Roman villa just outside Pocklington,[8] and although it is not known who occupied it, is suspected to have been a Romano-British chief.

In 2004 diggers excavating the site near Pocklington unearthed fragments of a human skeleton which almost certainly dated back to Roman times. A quantity of Roman era pottery dating back to between 70 AD and 410 AD has also been uncovered scattered across the same field.[3]

It is known that at least as early as the 4th century large tracts of land in the Pocklington area and the Wolds were granted to Germanic "Foederati" – continental warlords (possibly of the Alemanni) who were given areas of farmland in return for military service. It is not known to what extent this influx replaced or mingled with the earlier inhabitants.

Anglo-Saxon and Viking era

It was some time before 650 AD that Pocklington gained its current name, meaning "farmstead belonging to Pocela's people". It is not known what name Pocklington was known by before that date.

It is reputed that the ancient kingdom of Deira has its capital nearby. It is likely that the missionary Paulinus established the first Christian church in Pocklington on his way from Goodmanham to found York Minster. Certainly, the Sotheby Cross, dating from the late 14th century in the churchyard at All Saints' Church, has the inscription "Paulinus here preached and celebrated AD627".

The Great Heathen Army of the Vikings captured much of the area in 866, and, in 876, their remnants settled permanently in parts of the Yorkshire countryside. Viking kings ruled this area, known to historians as "The Viking Kingdom of Jorvik", for almost a century. In 954, the last Viking king, Eric Bloodaxe, was expelled and his kingdom was incorporated in the newly consolidated Anglo-Saxon state.

High Middle Ages in Pocklington

Many English towns are able to find mention of themselves in the Domesday Book, William the Conqueror's catalogue of the country. Even before the Norman Conquest, however, records of Pocklington are found in taxation census' of Anglo Saxon kings.

Pocklington steadily evolved from Anglo Saxon times as the centre of the surrounding agricultural area. Before the Norman conquest, when King Harold's brother-in-law Earl Morcar was Lord of the Manor, it was a prosperous settlement.

Late Middle Ages – medieval Pocklington

The Battle of Stamford Bridge was fought just 4 miles from Pocklington, and was the first of two major battles in that year for control of the country (the other being the Battle of Hastings. The former marked the end of Viking rule in England and the latter ushered in a period of Norman rule.

After the Norman conquest the manor at Pocklington became a royal manor – with the Percy family as the King's overlords – and under this royal patronage, Pocklington continued to prosper. Pocklington was recorded in the Domesday Book as "Poclinton"[1] and, given its current size, it is surprising to note that at the time of Domesday (1086) it is recorded as being the second largest settlement in Yorkshire after York itself, showing clearly that it had bounced back from its marginalisation in Roman Britain.

Pocklington developed through the Middle Ages while many similar places fell into dramatic decline. Pocklington owed much of its prosperity in the Middle Ages to the fact it was a local centre for the trading of wool[9] and that it lay on the main road to York, an important national centre for the export of wool to the Continent. Wool was England's principal export in the Middle Ages.

A weekly market and regular fairs in the town were held by Royal Charter in 1245. Regular fairs continued until the early 1900s.

The town's All Saints' Church is the only survivor from the Middle Ages. Known as the "Cathedral of the Wolds", it dates from the late 12th to early 15th centuries. Although containing some fragments of the earlier Norman church, its foundations go back further to the original Saxon era. The clerestory is 13th century and the tower is 15th.

Parish records show that the Black Death (the bubonic plague) struck Pocklington hard in 1350, a year after its first outbreak in London and the south coast.

Pocklington School was founded in 1514 as the Guild of the Parish Church by senior churchmen and politician John Dolman. His family became Lords of the Manor in the 14th century.

In 1400 Pocklington was one of 30 East Riding of Yorkshire settlements which could be termed market towns. By 1750 there were just 10 and Pocklington was one. Over the next 150 years the town trebled in size with a host of new trades joining existing agricultural, brewing and milling interests.

Early Modern Period in Pocklington

Pocklington has one of the few Cromwellian charters in the country. The town charter was granted on 8 September 1656, one of the few during Oliver Cromwell's 11 years.

Pocklington also lays claim to being the last place in England to hold a witch burning. In 1630 the parish register for that year records Old Wife Green burnt in Market for being a witch.

In 1848 a cache of more than 500 coins from 1500 to 1700 was found on the edge of town.

And 19 years later, the town's most notorious resident Isabella Bilington aged 32 was sentenced to death at York Assizes for crucifying her mother at Pocklington. After the killing she burnt a calf and a cock as a sacrifice. Her husband too was hanged as an accomplice.

Early Industrial Pocklington

William Wilberforce wrote his first public letter against the slave trade while at Pocklington School from 1771 to 1776 and went on to be the driving force behind the abolition of slavery in the early 19th century. This is celebrated by the broken linked chain in the present town coat of arms.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was a frequent visitor to Pocklington in the late 18th century, and is among several notable churchmen, bishops and titular archbishops, born or educated in the town. A Wesleyan Methodist Church survives in use in Pocklington to this day.

Entertainment also earned the town notoriety. The celebrated Flying Man of Pocklington, Thomas Pelling, attempted in 1733 to travel along a rope between the church and the Star Inn in the Market Square. He crashed to his death fracturing his skull against the wall of the church following a misunderstanding with men working the windlass. He is buried where he fell at the east end of the church where a plaque celebrates his memory.

In 1759 a Pocklington brewer called Timothy Overland received a piece of land on the York to Beverley road on the southern fringe of Pocklington and built the Pocklington New Inn. By 1778, the establishment was a prosperous Coach House at the height of the coaching era. The building is still in the same use today as the Pocklington Motel.

By this time the seat of the Lord of the Manor had transferred to Kilnwick Percy Hall. The present house was built in 1784 although there had been a hall there for many centuries. Unfortunately, a large section of it fell into disrepair and was pulled down during the 1940s. The remainder has (belatedly) been classed as a Grade II listed Georgian mansion.

19th century Pocklington

Steady further growth continued during the 19th century which saw much of the town completely rebuilt.

In 1814, an act of parliament was passed for making a navigable canal from East Cottingwith to Street Bridge (about a mile from Pocklington). An early draft of this Parliamentary act was recently discovered in the attic of a Pocklington house.[10] By 1818 the Pocklington Canal linked Pocklington to the River Derwent. It fell into disuse with the decline of Britain's canals but has been continuously resurrected by the Pocklington Canal Amenity Society since 1971 and the old mill house is now classed as a Grade II listed water mill of historic interest: most of the mill mechanism still exists.

In 1821, the entire parish contained 2,163 inhabitants, of which 1,962 were of the township of Pocklington itself.[11]

In 1868, Pocklington's inhabitants are described as being "for the most part employed in agricultural pursuits, and in ropemaking, brickmaking, brewing, and malting. There are besides corn mills, iron foundries, and agricultural implement manufactories which materially contribute to the industrial wealth of the town."[12]

In 1890, extensive repairs and alterations were made to All Saints' Church and, in a foreshadowing of modern interest in "time capsules", a message detailing the work was sealed in a glass bottle along with an 1890 newspaper and buried underneath the plith of the medieval Sotheby Cross. Unearthed accidentally during repairs in 2005, the sealed message and a copy of the 1890 newspaper were re-buried in the same spot, along with a contemporary copy of the Pocklington Post.[13]

20th century Pocklington

The group of five airfields based in and around Pocklington played an active role in the Second World War. Pocklington Airfield was completed in April 1941. The first operational unit to occupy Pocklington was the Canadian No. 405 Squadron with Wellington aircraft, but in 1942 the RAF's 102 (Ceylon) Squadron took over the airfield, flying night sorties to bomb targets in France. They still hold an annual reunion in Pocklington. It was disbanded on 20 October 1954.

During the Second World War a few houses in Pocklington were subject to bombing, after their street was mistaken for the airfield.

Those serving on HMS Volage also keep close ties with the town that adopted them during the war, sending letters and parcels. The association with Pocklington continues with a new housing estate being named 'Volage Court' in recognition of the links with HMS Volage.[14]

Pocklington used to be served by a railway connection but this was closed in the Beeching Report era of the 1960s. Some existing lengths of trackway can be seen behind the old railway station (now used as the sports hall for Pocklington School). There has been some talk of bringing the railway line back to Pocklington but there has been substantial development along the original line after the land was sold off and the original route is no longer practical. There are serious doubts also as to the financial feasibility of re-opening the line.

Pocklington experienced a rapid expansion in the final two decades of the 20th century, with large amounts of "green land" being ceded to new housing development to meet the demands of both lower housing occupancy rates (a trend common across the country) and also demand for commuter belt housing for the cities of York and Leeds.

Throughout its long history, Pocklington has faced difficult times like recession, wartime and the closing of the railway, but each time the town has overcome and gone on to develop further.

See also

References

- "Builders uncover Iron Age village in East Yorkshire". BBC News. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "Ancient bones may be Iron Age". The York Press. 11 September 2004. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- "Celtic warrior from 2,000 years ago buried in chariot with weapons and ponies hailed as most important find of its kind in UK". The Independent. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Iron Age shield found in Pocklington is "one of most important ancient finds this millennium"". Yorkshire Post. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Iron Age shield found in Pocklington is "one of most important ancient finds this millennium"". The Telegraph. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "In Praise of Pocklington". Yorkshire Today. Business Link Magazine Group. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 August 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Denison, Simon "One-upmanship in Roman Yorkshire", British Archaeology, no 30, December 1997, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Staff Writer "Ancient bones may be Iron Age", The Evening Press, 11 September 2004, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Pocklington Town Council "Pocklington's connection with HMS Volage", Pocklington Town Council website, 31 August 2006, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Pocklington Town Council "Pocklington Town Council", Pocklington Town Council website, 31 August 2006, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Staff Writer "Erasure of Town Heritage", Pocklington Post, 13 May 2005, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Staff Writer "Message in a bottle", Pocklington Post, 22 August 2005, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Hinson, Colin (tr.) "Pocklington", Pigot's National Commercial Directory for 1828–29, 9 August 2003, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Hinson, Colin (tr.) "Pocklington Parish", The National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland 1868, 8 August 2006, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Visit East Yorkshire "Welcome to the Wolds", Visit East Yorkshire, 2006, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Arundel, Chris "The Beverley to York Railway", BBC, 2006, retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Staff Writer "Ancient Yorkshire men copy Roman style", Yorkshire Post (Leeds), 15 September 1997, retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Halkon, Peter, Dr. "A Roman villa near Pocklington", Britannia, no. 30, 1998, retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Domesday Book "Pocklington, Yorkshire", National Archives, retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Staff Writer "Historical document found in attic", Pocklington Post, 10 July 2003, retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Mills, A D The Popular Dictionary of English Place-Names, Parragon, 1996 ISBN 0-7525-1851-8 (Based on A Dictionary of English Place-Names, OUP, 1991), retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus), "Geography", Book 2, Part 2 – "The Tribes and Cities of Mainland Britain"

- David Neave, Pocklington 1660–1914: A Small East Riding Market Town, Third Edition, W & C Forth