Abolitionism in the United Kingdom

Abolitionism in the United Kingdom was the movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to end the practice of slavery, whether formal or informal, in the United Kingdom, the British Empire and the world, including ending the Atlantic slave trade. It was part of a wider abolitionism movement in Western Europe and the Americas.

.jpg.webp)

The buying and selling of slaves was made illegal across the British Empire in 1807, but owning slaves was permitted until it was outlawed completely in 1833, beginning a process where from 1834 slaves became indentured "apprentices" to their former owners until emancipation was achieved for the majority by 1840 and for remaining exceptions by 1843. Former slave owners received formal compensation for their losses from the British government, known as compensated emancipation.

Origins

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, English Quakers and a few evangelical religious groups condemned slavery (by then applied mostly to Africans) as un-Christian. A few secular thinkers of the Enlightenment criticised it for violating the rights of man.[1] James Edward Oglethorpe was the first to operationalize the Enlightenment case against slavery, banning slavery in his Province of Georgia on humanistic grounds, arguing against it in Parliament and eventually encouraging his friends Granville Sharp and Hannah More vigorously to pursue the cause. Soon after his death in 1785, they joined with William Wilberforce and others in forming the Clapham Sect.[2] Oglethorpe's prohibition was reversed and all the American colonies rapidly built up slave systems.

The slave trade had been banned in England in 1102.[3] In a 1569 court case involving Cartwright, who had bought a slave from Russia, the court ruled that English law could not recognise slavery, as it was never established officially. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments. It was upheld in 1700 by Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt when he ruled that "As soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free".[4]

English colonists imported slaves to the North American colonies and by the 18th century, traders began to import slaves from Africa, India and East Asia (where they were trading) to London and Edinburgh to work as servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians have been documented in colonial records.[5][6] Historian David Olusoga wrote of the sea change that had taken place:

To fully understand how remarkable the rise of British abolitionism was, both as a political movement and as a popular sentiment, it is important to remember how few voices were raised against slavery in Britain until the last quarter of the eighteenth century.[7]

Some of the first freedom suits, court cases in Britain to challenge the legality of slavery, took place in Scotland in 1755 and 1769. The cases were Montgomery v. Sheddan (1755) and Spens v. Dalrymple (1769). Each of the slaves had been baptised in Scotland and challenged the legality of slavery. They set the precedent of legal procedure in British courts that would later lead to success for the plaintiffs. In these cases, deaths of the plaintiff and defendant, respectively, brought an end to the action before a court decision could be rendered.[8]

African slaves were not bought or sold in London itself but were brought by masters from other places. Together with people from other nations, especially non-Christian ones, Africans were considered foreigners and thus ineligible to be English subjects. At the time, England had no naturalisation procedure. The African slaves' legal status was unclear until the 1772 Somersett's Case, when the fugitive slave James Somersett forced a decision by the courts. Somersett had escaped and his master, Charles Steuart, had him captured and imprisoned on board a ship, intending to ship him to Jamaica to be resold into slavery. While in London, Somersett had been baptised and three godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result, Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King's Bench, had to judge whether Somersett's abduction was lawful or not under English Common Law. No legislation had ever been passed to establish slavery in England. The case received national attention and five advocates supported the action on behalf of Somersett.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772, Mansfield held,

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory. It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.[9]

Although the legal implications of the judgement are unclear when analysed by lawyers, the judgement was generally taken at the time to have determined that slavery did not exist under English common law and was thus prohibited in England.[10] As a result, by 1774, between 10,000 and 15,000 slaves gained freedom in England.[11] The decision did not apply to British overseas territories; e.g. the American colonies had established slavery by positive laws.[12] Somersett's case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English-speaking world and it helped launch the movement to abolish slavery.[13]

After reading about Somersett's Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African who had been purchased by his master John Wedderburn in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, left him. Married and with a child, he filed a freedom suit, on the grounds that he could not be held as a slave in Great Britain. In the case of Knight v. Wedderburn (1778), Wedderburn said that Knight owed him "perpetual servitude". The Court of Session of Scotland ruled against him, saying that chattel slavery was not recognised under the law of Scotland, and slaves could seek court protection to leave a master or avoid being forcibly removed from Scotland to be returned to slavery in the colonies.[8]

At this point the plantocracy became concerned, and got organised, setting up the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants to represent their views. From its inception in 1780, the organisation played a major role in resisting the abolition of the slave trade and that of slavery itself. The Society brought together three different groups: British sugar merchants, absentee planters and colonial agents.[14]

Writing critically of English altruism in abolishing the slave trade, African-American historian W. E. B. Du Bois in 1948 said,

The rise of liberal and philanthropic thought in the latter part of the eighteenth century accounts, of course, for no little of the growth of opposition to slavery and the slave trade; but it accounts for only a part of it. Other and dominant factors were the diminishing returns of the African slave trade itself, the bankruptcy of the West Indian sugar economy through the Haitian revolution, the interference of Napoleon and the competition of Spain. Without this pressure of economic forces, Parliament would not have yielded so easily to the abolition crusade. Moreover, new fields of investment and profit were being opened to Englishmen by the consolidation of the empire in India and by the acquisition of new spheres of influence in China and elsewhere. In Africa, British rule was actually strengthened by the anti-slavery crusade, for new territory was annexed and controlled under the aegis of emancipation. It would not be right to question for a moment the sincerity of Sharpe, Wilberforce, Buxton and their followers. But the moral force they represented would have met with greater resistance had it not been working along lines favorable to English investment and colonial profit.[15]

Activists organize

Antislavery sentiment may have grown in the British Isles in the first few years after the Somersett case. In 1774, influenced by the case and by the writings of Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet, John Wesley, the leader of the Methodist tendency in the Church of England, published Thoughts Upon Slavery, in which he passionately criticized the practice.[18] In his 1776 A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals, the clergyman Humphry Primatt wrote, "the white man (notwithstanding the barbarity of custom and prejudice), can have no right, by virtue of his colour, to enslave and tyrannize over a black man."[19] In 1781 the Dublin Universal Free Debating Society challenged its members to consider if "enslaving the Negro race [is] justifiable on principles of humanity of [sic] policy?"[20]

Despite the ending of slavery in Great Britain, the West Indian colonies of the British Empire continued to practice it. British banks continued to finance the commodities and shipping industries in the colonies they had earlier established which still relied upon slavery, despite the legal developments in Great Britain.[21] In 1785, the English poet William Cowper wrote,

We have no slaves at home.—Then why abroad?

And they themselves once ferried o'er the wave

That parts us, are emancipate and loos'd.

Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs

Receive our air, that moment they are free,

They touch our country and their shackles fall.

That's noble, and bespeaks a nation proud

And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then,

And let it circulate through ev'ry vein

Of all your empire. That where Britain's power

Is felt, mankind may feel her mercy too.(from The Task, Book 2)[22]

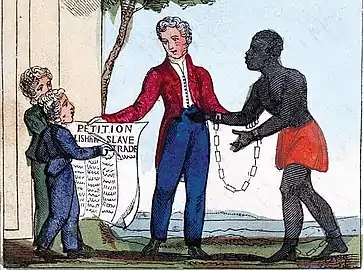

In 1783, an anti-slavery movement began in Britain. That year a group of Quakers founded their first abolitionist organization. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the lifetime of the movement, in many ways leading the campaign.[23] On 17 June 1783, Sir Cecil Wray (one of the Members of Parliament for Westminster) presented the Quaker petition to parliament. Also in 1783, Dr Beilby Porteus, Bishop of Chester, issued a call to the Church of England to cease its involvement in the slave trade and to formulate a policy to improve the conditions of Afro-Caribbean slaves. The exploration of the African continent by such British groups as the African Association (1788) promoted the abolitionists' cause. Such expeditions highlighted the sophistication of African social organisation; before this, Europeans had considered them 'other' and uncivilized. The African Association had close ties with William Wilberforce, who became known as a prominent figure in the campaign for abolition in the British Empire.[24]

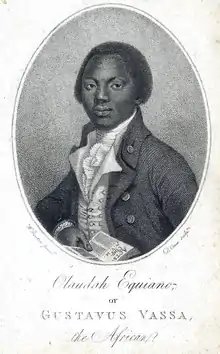

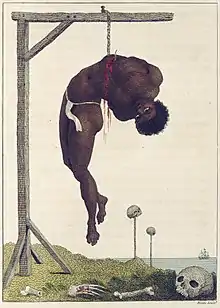

Africans themselves played a visible role in the abolition movement. In Britain, Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiography was published in nine editions in his lifetime, campaigned tirelessly against the slave trade. More important were horrific images such as the famous Wedgwood medallion of 1787 and the engraving showing the ghastly layout of the slave ship, the Brookes.[25]

Growth of the movement

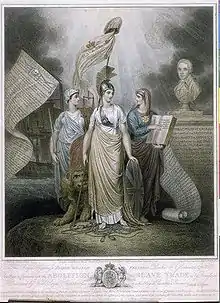

After the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787, William Wilberforce led the cause of abolition through the parliamentary campaign. It finally abolished the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. He continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, which he lived to see in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The Atlantic slave trade, also called Triangle trade, encompassed the trafficking in slaves by British merchants who exported manufactured goods from ports such as Bristol and Liverpool, sold or exchanged these for slaves in West Africa (where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery), and shipped the slaves to British colonies and other Caribbean countries or the American colonies. There traders sold or exchanged the slaves for rum and sugar (in the Caribbean) and tobacco and rice (in the American South), which they took back to British ports. The merchants traded in three places with each round-trip. Political influence against the inhumanity of the slave trade grew strongly in the late 18th century.

Europeans and Africans worked for abolition of the slave trade and slavery. Well-known abolitionists in Britain included James Ramsay, who had seen the cruelty of the trade at first hand; the Unitarian William Roscoe who courageously campaigned for parliament in the port city of Liverpool for which he was briefly M.P., Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood, who produced the "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?" medallion for the Committee; and other members of the Clapham Sect of evangelical reformers, as well as Quakers.

Quakers made up most of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and were the first to present a petition against the slave trade to the British Parliament. As Dissenters, Quakers were not eligible to become British MPs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Anglican evangelist William Wilberforce led the parliamentary campaign. Clarkson became the group's most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of data and gaining first-hand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

Mainly because of Clarkson's efforts, a network of local abolition groups was established in England. They campaigned through public meetings and the publication of pamphlets and petitions. One of the earliest books promoted by Clarkson and the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was the autobiography of the freed slave Olaudah Equiano. The movement had support from such freed slaves, from many denominational groups such as Swedenborgians, Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and others. They reached out for support from the new industrial workers of the cities in the Midlands and north of England. Even women and children, previously un-politicised groups, became involved in the campaign. At this time, women often had to hold separate meetings as there were social rules against their appearing in public meetings. They could not vote, nor could the majority of the men in Britain at the time.

The abolitionists negotiated with chieftains in West Africa to purchase land to establish 'Freetown' – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire (the Poor Blacks of London) and the United States. Great Britain had promised freedom to American slaves who left rebel owners to join its cause during the American Revolutionary War. It evacuated thousands of slaves together with its troops and transported 3,000 Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia for resettlement. About a decade later, they were offered a chance to resettle in Freetown and several hundred made the move. Freetown was the first settlement of the colony of Sierra Leone, which was protected under a British Act of Parliament in 1807–08. British influence in West Africa grew through a series of negotiations with local chieftains to end trading in slaves. These included agreements to permit British navy ships to intercept chieftains' ships to ensure their merchants were not carrying slaves.

Also from 1800 the Royal African Corps was recruited from West African volunteers, and eventually included freed slaves from the Caribbean before it was disbanded in 1819.

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to the Dutch-controlled Surinam in South America as part of a military force sent out to subdue bosnegers, former slaves living in the interior. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It was an example of what became a large body of abolitionist literature.

Slave Trade Act 1807

The Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire. The Act imposed a fine of £100 for every slave found aboard a British ship. At a time when Napoleon decided to revive slavery, which had been abolished during the French Revolution and to send his troops to re-enslave the people of Haiti, Guadeloupe and the other French Caribbean possessions, the British took the moral high ground with their prohibition of the slave trade.[source?]

Slave Trade Felony Act 1811

The 1807 act’s intention was to entirely outlaw the slave trade within the British Empire, but the lucrative trade continued through smuggling. Sometimes captains at risk of being caught by the Royal Navy would throw slaves into the sea to reduce their fines. Abolitionist Henry Brougham realized that trading would continue, and so as a new MP successfully introduced the Slave Trade Felony Act 1811. This law at last made slave trading a criminal felony throughout the empire, and for British subjects worldwide. This proved far more effective and ended the trade across the Empire, as the Royal Navy ruthlessly pursued slave ships. In 1827, Britain defined participation in the slave trade as piracy and punishable by death. Between 1808 and 1860, the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.[26] Britain used its influence to coerce other countries to agree to treaties to end their slave trade and allow the Royal Navy to seize their slave ships.[27][28] Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade. For example, in 1851 it deposed “the usurping King of Lagos”. Britain signed anti-slavery treaties with more than 50 African rulers.[29]

Slavery Abolition Act 1833

After the 1807 Act, enslaved persons could still be held, though not sold, within the British Empire. In the 1820s, the abolitionist movement may have revived the campaign against the institution of slavery. In 1823 the first Anti-Slavery Society was founded in Britain. The Society's members consisted of a union of non-conformist churches and many had previously campaigned against the slave trade.[30] In 1831, enslaved man Sam Sharpe led the Christmas Rebellion (Baptist War) in Jamaica, an event that catalyzed anti-slavery sentiment. This combination of political pressure and popular uprisings convinced the British government that there was no longer any middle ground between slavery and emancipation.[31]

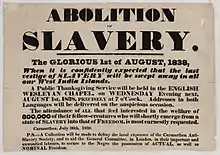

On 28 August 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act received Royal Assent, paving the way for the abolition of slavery within the British Empire and its colonies. On 1 August 1834, all enslaved persons in the British Empire (except for India) were emancipated, but they were indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system that meant gradual abolition: the first set of apprenticeships came to an end on 1 August 1838, while the final apprenticeships were scheduled to cease on 1 August 1840, two years later.[32]

The apprenticeship system was deeply unpopular with enslaved persons. On 1 August 1834, as the Governor in Port of Spain, Trinidad addressed an audience about the new laws, the mostly elderly, unarmed enslaved persons began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out his voice. Peaceful protests continued until the government passed a resolution to abolish apprenticeship and the enslaved persons gained de facto freedom. Full emancipation for all enslaved persons was legally granted on 1 August 1838, ahead of schedule, making Trinidad the first British slave society to fully end slavery.[33] The government set aside £20 million for compensation of slave owners for their "property" across the Empire, but it did not offer formerly enslaved people compensation or reparations.[34] This was because abolitionists had not planned for much more than the long-awaited reform of the law, and felt that freedom along with the option of returning to Africa to live in Freetown, or the nearby state of Liberia, was infinitely preferable to continued chattel slavery.

In context, the £20 million voted by Parliament to compensate slave owners under the 1833 Act can be compared with the Gross Domestic Product of the UK in 1832, which was £459 million.[35]

Campaigning after the act

In 1839, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society was formed. At the time, the British economy continued to import cotton and other commodities from the U.S. Deep South, which relied on slavery for cotton production, to fuel the spinning and weaving mills in Manchester and other northern cities. The finished goods furnished Britain's low-wage, export, manufacturing economy with surpluses exported to Europe and India. London merchant-banks made loans throughout the supply-chain to planters, factors, ware-housers, carters, shippers, spinners, weavers, and exporters.[21]

The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society campaigned to outlaw slavery in other countries and pressured the British government to do more to enforce the suppression of the slave trade, by declaring slave traders to be pirates and pursuing them as such. It is in operation today as Anti-Slavery International, the world's oldest international human rights organisation.[36]

On 20 December 1841, the first multilateral treaty for the suppression of the slave trade, the Treaty for the Suppression of the African Slave Trade, was signed in London by the representatives of Austria, Britain, France, Prussia and Russia.[37][38]

See also

- Abolition of slavery timeline

- Abolitionism in the United States

- Abolitionism in France

- Abolitionism and paintings of Queen Charlotte

- List of Abolitionist Forerunners (Thomas Clarkson)

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

- Slavery in the British Isles

- Slavery in the British Virgin Islands

References

- Matthew Wyman‐McCarthy, "British abolitionism and global empire in the late 18th century: A historiographic overview." History Compass 16.10 (2018) .

- Wilson, Thomas D (2012). The Oglethorpe Plan: Enlightenment Design in Savannah and Beyond. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 201–206. ISBN 9780813932903. OCLC 907676628.

- "The Viking slave trade: entrepreneurs or heathen slavers?". History Ireland. 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- Mtubani, V. C. D. (1981). "African Slaves and English Law" (PDF). Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies. 3 (2): 71–75. ISSN 0256-2316.

- Heinegg, Paul. "Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware". www.freeafricanamericans.com. Retrieved 2019-08-09., "WEAVER FAMILY: Three members of the Weaver family, probably brothers, were called "East Indians" in Lancaster County,[VA] [court records] between 1707 and 1711."; "'The indenture of Indians (Native Americans) as servants was not common in Maryland ... the indenture of East Indian servants was more common.", Retrieved 15 February 2008

- Francis C. Assisi, "First Indian-American Identified: Mary Fisher, Born 1680 in Maryland" Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, IndoLink, Quote: "Documents available from American archival sources of the colonial period now confirm the presence of indentured servants or slaves who were brought from the Indian subcontinent, via England, to work for their European American masters.", Retrieved 20 April 2010

- Black and British: A Forgotten History

- "Slavery, freedom or perpetual servitude? – the Joseph Knight case". National Archives of Scotland. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Moncreiff, Frederick Charles (2006). The Wit and Wisdom of the Bench and Bar. Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781584777243. OCLC 65538391.

- Mowat, Robert Balmain; Slosson, Preston William (1943). History of the English Speaking Peoples. London: Oxford University Press. p. 162. OCLC 560320214.

- Murrin, John M (2013). Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Volume I: To 1877 (Concise sixth ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. p. 119. ISBN 9781133947738. OCLC 857231893.

- MacEwen, Martin (2002). Housing, Race and Law: The British Experience. London: Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 9780203032428. OCLC 1086444682.

- Hinks, Peter P; McKivigan, John R; Williams, R. Owen (2007). Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 643. ISBN 9780313015243. OCLC 230763683.

- Butler, Kathleen Mary (1995). The Economics of Emancipation: Jamaica & Barbados, 1823-1843. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books. p. 8.

- Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt (July 1, 1943). "The Realities in Africa: European Profit or Negro Development?". Foreign Affairs. Vol. 21 no. 4. ISSN 0015-7120.

- Walvin, James (1997). "Ignatius Sancho: The Man and His Times". In King, Reyahn (ed.). Ignatius Sancho: an African Man of Letters. London, UK: National Portrait Gallery. p. 96.

- Carey, Brycchan. "Ignatius Sancho: African Man of Letters". Brycchan Carey. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- Carey, Brycchan (2002). "John Wesley (1703-1791)". Brycchan Carey. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Primatt, Humphry (1776). A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals. London: R. Hett. p. 11.

- Higgins, Padhraig (2010). A Nation of Politicians: Gender, Patriotism, and Political Culture in Late Eighteenth-Century Ireland. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 10.

- Christopher Hollis: Two Nations: A Financial Study of English History

- Cowper, William, The task: a poem, in six books. By William Cowper, ... (London: printed for J. Johnson, 1785), p. 47. Online at "Eighteenth Century Texts Online"

- Tomkins, Stephen (22 March 2007). "BBC NEWS | Magazine | Keeping it under their hats". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- Hague, William (2008). William Wilberforce: The Life of the Great Anti-Slave Trade Campaigner. London: Harper Perennial. p. 327. ISBN 9780007228867. OCLC 192026996.

- McGrath, Elizabeth; Massing, Jean Michel (2012). The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem. London: Warburg Institute. ISBN 9781908590435. OCLC 811970449.

- Loosemore, Jo (2008-07-08). "Sailing against slavery". BBC. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007). Encyclopedia of the middle passage. Greenwood Press. pp. xxi, xxxiii–xxxiv. ISBN 9780313334801.

- "The legal and diplomatic background to the seizure of foreign vessels by the Royal Navy".

- "The West African Squadron and slave trade". pdavis.nl. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- "Why was Slavery finally abolished in the British Empire?". The Abolition of Slavery Project. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- Drescher, Seymour (2000). "Abolitionist expectations: Britain". Slavery & Abolition. Informa UK Limited. 21 (2): 53. doi:10.1080/01440390008575305. ISSN 0144-039X. S2CID 145059848.

- Oldfield, Dr John (February 17, 2011). "British Anti-slavery". BBC History. BBC. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

the new legislation called for the gradual abolition of slavery. Everyone over the age of six on August 1, 1834, when the law went into effect, was required to serve an apprenticeship of four years in the case of domestics and six years in the case of field hands

- Dryden, John. 1992 "Pas de Six Ans!", In: Seven Slaves & Slavery: Trinidad 1777–1838, by Anthony de Verteuil, Port of Spain, pp. 371–379.

- "Slavery Abolition Act 1833". 28 August 1833. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- "Public Spending Details for 1832". UK Public Spending. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- "Anti-Slavery International". UNESCO Education. 2006. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- Lewis Hertslet (ed.), A Complete Collection of the Treaties and Conventions, and Reciprocal Regulations, at Present Subsisting Between Great Britain and Foreign Powers, vol. 6 (London, 1845), pp. 2-20. On Google Books.

- Randall Lesaffer, Vienna and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Oxford Public International Law, 2020.

Further reading

- Bader-Zaar, Birgitta: Abolitionism in the Atlantic World: The Organization and Interaction of Anti-Slavery Movements in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2010, retrieved: June 14, 2012.

- Brown, Christopher Leslie. Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (2006)

- Davis, David Brion, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (1999); The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1988)

- Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (2009)

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of Slavery (1999)

- Gould, Philip. Barbaric Traffic: Commerce and Antislavery in the 18th-century Atlantic World (2003)

- Hinks, Peter, and John McKivigan, eds. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition (2 vol. 2006) ISBN 0-313-33142-1; 846pp; 300 articles by experts

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains, Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves (2005)

- Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America (2008)

- Olusoga, David. Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016)

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. "Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World" (2007)

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery (1997)

- Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution (London: BBC Books, 2005) (New York: Ecco, 2006 )

- Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870 (2006).

- Wyman‐McCarthy, Matthew. "British abolitionism and global empire in the late 18th century: A historiographic overview." History Compass 16.10 (2018): e12480.