History of Routledge surname 15th to 18th centuries

People with the surname Routledge, and its numerous variant spellings, are first found in historical records living along the Anglo Scottish border. During these 400 years, many volatile events directly affected the lifestyles of every border family, from tenant farmer to landlord to border official. Border inhabitants, commoner and aristocrat alike, lived through intermittent warfare, violent religious reforms, and periods of famine and pestilence. Under such constant stress, civility broke down the predominantly agricultural society based on feudal tenure. Lawlessness prevailed whereby the term Border Reiver (raider) characterized about 75 surnames, Routledge included, that engaged in livestock rustling as normal activity. Many Routledge men and their peers lived and died by the sword as the following chronology will attest. History recorded their misdeeds and misfortunes without acknowledging any joys and pleasures they might have experienced during these times. Ultimately, some of these rough and ready Routledges survived to move on and thrive in all walks of life in all parts of the modern world. The quoted sources listed below place them within context of the powerful forces that defined their lives and recorded their names for posterity.

Routledge in the 15th Century

Routledge and Douglas of Roxburghshire Scotland

AD 1400. To date, Routledge families have been recorded living in Hawick and Cavers, communities located alongside the River Teviot, often referred to as Teviotdale, in the southeast region of Scotland, adjacent to the English counties of Northumberland and Cumbria. The earliest documents indicate that they occupied respectable positions as officials for the powerful Douglas family, overlords of much of the county of Roxburghshire. Two main Douglas factions influenced Scottish politics and social life of the day: the so-called "Black" Douglases headed by the Earls of Douglas and the "Red" Douglases headed by the Earls of Angus. According to documents so far uncovered, Routledges were aligned with cadet barons of the "Black" Douglases at the beginning of the 15th century.

Just as the place-name "Roxburgh" appears in historic records with numerous spellings—anything from "Rokysburgh" to "Rocheburch,"[1][2] likewise the same peculiarities apply to most surnames, and Routledge is no exception. Many more imaginative forms occur other than the commonly accepted alternative of "Rutledge," for example: Rootlige, Rutlage, Routleche, Rutliche, Routleidge, Rouchligis, Rudlege, Rowledge, Routelych, Rutley, Ratlish, Rookledge, Rowtledge, Routleach, Rouchelug, Rotheluge, Rotheloige, Routlagh, Rowtlugh, to name only a few. NOTE: Spelling throughout this chronology is given as in the original document.

Routledge, Douglas and Lands of Crouk

AD 1429. William Routlech, son of the deceased John Routlech, resigned his rights to half of his lands of Crouk located in the parish of Cavers, Scottish Borders to an "honourable man" by the name of James Douglas on behalf of Martin Douglas. The document asserts that William had these lands by "the kindness" of one James Routlech, implying that the word "kindness" in this context either referred to previous generations of Routledge families holding the land by hereditary right or by friendly permission of the landlord.[3] The transaction was done in the "Parish Church of Caveris in presence of Thomas Rutherfurd, Sir James Zung [Young?], canon, John Scot in Orchart, elder and younger, and Thomas Runseman, 15 January 1429-30."[4] NOTE: Some historians claim the date was incorrectly ascribed and should be 1529, not 1429.

Routledge, Douglas and Lands of Birkwood and Burnflat

AD 1433. William of Douglas, Lord of Drumlanrig, granted a Feu Charter [feudal tenure of land wherein the vassal returned money or grain instead of military service] to Symon de Routluge describing the lands of Birkwood and Burnflat.[5][6] Notably, the use of "de" before a surname normally referred to a specific place, though no such place has been found, unless it be "Roughley" in nearby Liddesdale. According to Douglas Scott, author of "A Hawick Wordbook," Roughley is a "farmstead" dating back to 1365, to the "east of Hermitage off the Roughley Burn."[7] Given the many outlandish spellings of early documents, it could be argued if not proved that Roughley is a transcription or dialect corruption of Routledge similar to that of other medieval documents.

AD 1453. Simon Routledge was one of two baileys [barony officer or town magistrate] to witness a legal document between John Turnbule of Cavillyng and Robert Wayte, burgess of Hawick before Sir Archibald Douglas of Caveris, knight, sheriff of Roxburgh.[8]

Demise of the Earls of Douglas — Rise of the Scotts of Buccleuch

AD 1440. In the mid-1400s, jealousy and treachery ran rife among Scotland's great landowners, with earls and barons across the land scheming for control of the young King James II (1437-1460). The "black" Douglases, in particular, were seen to be growing too powerful and, in 1440, sixteen-year-old William, the 6th Earl of Douglas and third Dếuke of Touraine (France), was lured to Edinburgh Castle on some sham pretext only to be seized, tried, and beheaded along with his younger brother David.

AD 1452. Once again an Earl of Douglas came to a brutal end when William, the 8th Earl of Douglas (1425-1452), was invited to Stirling Castle for a friendly dinner with King James. After dinner, the king demanded that William end certain alliances with nobles deemed to be a threat. William refused. Furious, the king grabbed a dagger and stabbed his stubborn vassal to death: "'Then this shall [end it],' said the king, and he twice stabbed his guest. 'Sir Patrick Grey...no safe neighbour if the Douglas were at disadvantage, came up and felled him with a pole-axe. His body was cast from the chamber window into the court below."[9]

AD 1455. Outrage over the killing of the 6th and 8th Earls of Douglas spawned open rebellion among Douglas followers. At this turn of events, the Scotts of Buccleuch seized an opportunity to advance their own interests. Assembling an opposing troop of borderers, Sir Walter Scott, his son David, and related Scotts of Kirkurd joined George Douglas, 4th Earl of Angus who was chief of the so-called "Red" line of Douglases and who had his own reasons for supporting the king against his "Black" Douglas cousins. A desperate melee ensued at the Battle of Arkinholm (now Langholm on the River Esk) on May 1, 1455, resulting in a rout for James Douglas, 9th Earl of Douglas. In June 1455, he and his heirs were declared forfeited, and the king's supporters, including Angus and Scott, acquired most of their lands in Roxburgh and Selkirk.[10] Evidence of exactly how the Routledges fit into these events has yet to be found, but it may be surmised that they rode with the Black Douglas faction as their feudal lords.

AD 1464. On the 6th of February, Simon of Routlagh witnessed an "Instrument of seisin" [possession], certifying that "John of Anysle, laird of Dolfinstone, sheriff of Roxburgh, specially deputed in that part by letters patent of the King, gave seisin and heritable state to Archibald of Dowglas by interposition of earth, wood, and stone as use was, of all the lands of the regality of the barony of Caverys, together with the office of the sheriffship of Roxburgh. Done at the manor place of Caverys, present, James of Dowglas, James Scot, George of Dowglas, Simon of Routlagh esquires, and others."[11]

AD 1484. On the 19th October, Symonem Rowtlugh was among a list of men witnessing the "retour" [return] of James Douglas, as heir of his father, William Douglas of Drumlangrig, in the barony of Hawick.[12]

AD 1508. David Routledge, sergeando [possibly a Latinized term for a castle official] was a witness for the 2nd Earl of Bothwell (Adam Hepburn), lord of Liddesdale. Douglases had held Liddesdale until 1491 when Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Angus (1449-1513), resigned the lordship over to the Hepburns.[13]

AD 1511. Mathew Routledge witnessed a "Sasine" [delivery of feudal property] of William Dowglas of Drumlanark [Drumlanrig], knight, in the town of Hawick.[14]

AD 1512. Dated at Jedburgh 14 January 1512-13, David Routlege witnessed a charter by "William Douglas of Drumlanrig knight and lord of the barony of Hawick, granting and selling to Alexander Lord Home great chamberlain of Scotland, the lands of Braidlie in the barony of Hawick and sheriffdom of Roxburgh. To be held of the granter and his heirs for a blench duty of a red rose at Midsummer. Witnesses, Andrew Ker of Fairneyhirst, Andrew Macdowall of Mackerstouon, William Maitland, William Scot, David Routlege and James Blair."[15]

AD 1512. David Routlesche witnessed a "precept [deed] of seizin [possession] by James Douglas of Caveris directing David Routlesche, Andrew Cranstoun, and others his baileys [bailiffs] in that part to give heritable seizin to William Cranstoun of that ilk, knight, of all and whole the ten pound lands of the granter's dominical lands of Dennome [Denholm] and various other lands specified in the preceding, in the barony of Cavers and shire of Roxburgh, which lands belonged to the said William heritably."[11]

AD 1514. English raiders attacked Hawick but were routed by the town's youth. It is presumed that Routledges, as citizens of Hawick, were involved when, as recounted by historian Robert Wilson, "a marauding party of the English, the year after the Battle of Flodden [1513] came up the Teviot for plunder...Recollections of Flodden sharpened the revenge of the people...about 200 stout men...met the English plunderers at Trows, two miles below Hawick, where a desperate conflict took place. The enemy, about forty in number, with a flag were come upon rather by surprise...a complete massacre ensued. The flag was taken and scarcely a soldier escaped. This colour or its emblem has been carried round the marches of the burgh property at the Common Riding ever since."[16]

AD 1537. James Douglas of Drumlanrig ordered a new charter for the town of Hawick, replacing an earlier one that had been lost and certifying land distribution. Hawick citizens mentioned in the charter included one David Rutlethe or Routlach who received "eight particates," [one particate = about one-quarter of a Scots acre],[17] second only in size to that of William Scott who received 11 particates. This charter is significant because it was written at a period when "vassal" rights were "precarious" due to the might-makes-right mentality that prevailed during these times. Later on, when Hawick became a corporation, the Charter became the "measure" of property rights.[18]

Routledge and Scott of Buccleuch

AD 1446. Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch had made a deal significant to his rise in power about 10 years prior to the stand-off at the Battle of Arkinholm. In 1446 he held half of Branxholm, a Teviotdale estate located about 3 miles southwest of Hawick Roxburgh. Sir Walter extended his ownership to much of the other half of Branxholm through a land exchange with Thomas Inglis. Scott gave over his lands of Murthoustoun [Murthockston] and Hertwod, in the barony of Bothwell Lanarkshire and received from Inglis the lands at Todschawhil, Todschawhauch, Goldylandis, Quhitlaw [Whitelaw], and Quhiteryg, with a fourth part of the lands of Overharwode in the barony of Hawick in the Shire of Roxburgh.

Routledge, Scott and the Branxholm Estate

AD 1447. One other party had an interest in the Branxholm estate at this time. One Symonis de Routluge held a portion called "Cusingisland" through his wife Margaret Cusing or Cusyne, and Scott wanted that piece of land to consolidate his position as a major landholder in Teviotdale. Curiously, this charter makes no mention of the purchase amount, suggesting the possibility that it is a copy made at some later date.[19][20][21]

Routledge, Scott and the Birkwood and Burnflat Estates

AD 1448. Symon of Routlug served as "bailie" [municipal officer or magistrate] for Hawick and, since 1433, had held there the lands of Birkwood and Burnflat, which Sir Walter Scott determined to acquire in addition to the Branxholm lands formerly held by Margaret and Symon de Routlug. The costs, terms, and conditions of this transfer of property are not given, but accordingly with subsequent events in 1494, it is quite possible that the arrangement was not mutually amicable.[22][23]

Routledge and Liddesdale Scotland, Bewcastle England

AD 1480s. While King James III of Scotland (1451-1488) struggled to maintain control of his ever-rebellious nobility, his younger brother Alexander Duke of Albany and the exiled Earl of Douglas were in England conspiring with King Edward IV (1442-1483) who was contending with rebellions of his own. The Wars of the Roses raged on between the Yorkist and Lancastrian factions of the Plantaganet dynasty regardless of intermittent hostilities erupting among the turbulent inhabitants along both sides of the English/Scottish border.

During this time, King Edward's brother, Richard (1452-1485) Duke of Gloucester and later King Richard III, had management of England's northern territories, including an appointment, in 1471, as Warden of the English West March and governorship of the ancient fortress city of Carlisle, Cumbria along with nearby royal estates at Bewcastle and Nicholforest. Additionally, Gloucester had permission to create a "buffer state" in Scotland if he could take control of Scottish territory in Eskdale, Annandale, Wauchopedale, Clydesdale, and especially Liddesdale where many fierce border raiders lived. Liddesdale and its formidable stronghold, Hermitage Castle, lie about 20 miles southeast of Hawick. After witnessing nearly two centuries of cross-border political intrigue and turmoil, the people living thereabouts had little loyalty for one king or the other. Borderers, including some Routledges, would pledge allegiance to whichever side suited their current needs.

.jpg.webp)

AD 1485. Depositions taken in evidence in 1538, over a Bewcastle land dispute, indicate that Cuthbert and John Routlege had been enticed to England by Gloucester's offer to acquire land, as attested by 80-year-old James Noble of Kirkbekmouth, and others.

. . .60 years 'bipast' when the Liddisdale men came into England and were sworn to King Richard at Carlisle...Sir Richard Ratcliff and three others, King Richard's commissioners, let all the lands of Bewcastle to Cuthbert and John Routlege, Robert Elwald and Gerard Nyxon...as well the said castle and all the lands belonging to the same. . .The said four men paid no rent to Lord Dacre or any other, but were 'to maintain the King's wars and to keep the borders.'[24]

Routledge, Douglas, Scott feud

AD 1494. The Scotts of Buccleuch had fared very well in the decades following the forfeited Earls of Douglas and their vassals. It is a reasonable assumption that certain Douglas and Routledge descendants burned with indignation over the loss of their lands to the upstart Scotts of Buccleuch. These were ruthless times when rival clans commonly settled disputes by punitive even murderous raids. Thus, in 1494 the Buccleuch manor house was raided and burned by Simon Routlage in the Trowis [a place near Hawick], Matthew his son and their accomplices, "after removing the cattle, horses, and sheep, plundered the mansion and set it on fire." Perhaps these raiders went under orders from William Douglas or possibly only with his blessing, but either way the two families subsequently appeared jointly before the courts of the day. They were summoned to appear before the Justice Air of Jedburgh, and "William of Douglas of Hornyshole [Hornshole] became surety for the satisfaction of the injured party."

Claiming damages of 1,000 Scottish "merks," Walter Scott, grandson of the deceased David Scott of Buccleuch, obtained, on 25 June 1494, a "decreet" against the "depredators" for the loss of "five horses and mares, forty kye and oxen, forty sheep, household plenishing to the value of 40 pounds, two chalders of victual, 30 salt martis, 80 stones of cheese and butter, and two oxen." Subsequently, on October 11, the Council of Lords "assigned to Walter Scott to prove the avail of the goods, and the damage alleged to extend to 1000 merks, and that the party be warned to hear them sworn.". . .(Acta Dominorum Concilii, p 338.)[25]

AD 1501. By this time, at least one Routledge family was well acquainted with settling disputes by vengeful means, and, if given names are any proof, they were probably descendants of Simon Routledge who had lost all of his Hawick and Branxholm lands to the Scotts of Buccleuch in the mid-1400s. In the Scottish Exchequer Rolls Mathei Routlich, Jacobi Routlich, Johannis Routlich, and Symonis Routlich were listed among a group of 25 mostly Rutherford men whose fines for some mischief had been compounded and charged to Walter Ker of Cessford and Henry Haitle of Mellostanis. Evidently Ker and Haitle, as landlords, had been required to stand as "surety" for the crimes of their tenants. The specific crimes are not disclosed but likely had to do with one of the many clan feuds typical of this era.[26]

AD 1510. More evidence that certain Routledges held a grudge against the Scotts of Buccleuch comes via the indictment of one John Dalgleish who must have had his own reasons for attacking the powerful Buccleuch clan. John Dalglese [Dalgleish] was indicted for the "treasonable in-bringing of Black John Roucleche and his accomplices, traitors of Leven [Line River, Bewcastle England], to the burning of Branxham, and the hereschip [plunder] of horses, oxen, grain, and other goods, extending to [??] markis, and...And because he could not find sureties to satisfy the parties, judgment was given that he [John Dalgleish] should be warded by the Sheriff forty days; and, if he could not find sureties in the meantime, that he should be hanged.[27]

Routledge in the 16th Century

AD 1510 to 1530. Rival factions vied for control of the infant King James V of Scotland (1512-1542) and, as in the previous century, Douglases were aiming for ultimate power: in 1514, hardly a year after the death of her husband James IV, the Dowager Queen Mother, Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), married Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus (1489-1557). That truculent marriage eventually ended in divorce but in the meantime was only one force at work against the tranquillity of Scotland. While Margaret's faction gained support from James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran (1475-1529), Angus headed an English faction conspiring with Margaret's brother, Henry VIII of England (1491-1547). Henry was bent on gaining sovereignty of Scotland by marrying young James to his daughter, the Princess Mary (1516-1558). A pro-French faction also held sway under John Stewart, Duke of Albany (1481-1536) who had been born and raised in France.

AD 1525-1526. In January 1526, Walter Scott of Branxholme and Buccleuch (1504-1552), led a party of 150 men against the Earl of Arran and the pro-Margaret side. It isn't clear whether this move was in support of any particular faction. Most likely Buccleuch was simply manoeuvring for future favour from King James who was bound to come into his own sooner or later, in which case, his assumption proved correct as evidenced by a letter of pardon from James. What the Routledges had to gain in this scenario is anybody's guess, but John and Archibald Routlage appear among a long list of names to be pardoned along with "Walter Scot of Branxhelme, knycht, Andro Ker of Prymside, John Cranstoun of that Ilk, William Stewart of Tracquar, James Stewart his bruther. . .and ilkane of thame for thair tresonable art and part of convocatioun of our liegis [and coming] in feir of weir. . ."[28][29]

Routledge and Border Reivers

AD 1520s-1530s. People living along the Scottish/English border were so entangled in their dual heritage during the previous 200 years of intermittent warfare that they hardly knew or cared to which king or country they owed allegiance. Duty to family assumed utmost importance. When called upon during frequent hostilities either between the two countries or, just as often, between feuding overlords, nobility and commoner alike would don their steel helmets and pikes, saddle their "nags," as their small but robust horses were called, and head into a fray on one side or the other—but only to the extent it suited each man's own purpose.

During truce or peace times, with their homelands neglected or ravaged by fire and sword, borderers, prompted by physical need or self-righteous anger, made a living rustling livestock, usually by cross-border incursions into enemy territory or maybe even closer to home if some feud or another needed settling. Rather than planting crops only to see them razed to the ground, reiving became normal routine for border inhabitants. Some 70+ surnames, including certain Routlege families, made a sporting game of these raiding activities, and the prize was booty; any goods that could be carried or livestock herded was fair game. Reiving parties sallied forth on horseback over bog and moss trails known only to the initiated. Sooner or later "hot-trod" posses and/or retaliation raids followed wherein the victims became perpetrators. Betrayal, ambush, and blind-siding all had a place in the game so that a raid might turn into a rout.[30]

Ludicrously, the political elite of both countries branded the reiving surnames as thieves and traitors, which would have been true enough if the so-called authorities had included themselves in those criminal categories. History shows that kings to nobles to officers of both crowns either complicitly or actively employed marauding tactics, each and all claiming their ends justified whatever means. In actuality, what was really happening was the beginning of the end of a centuries-old feudal system that kept the common-born population firmly under control of one noble-born master or another.

Routledge families lived on both the English and Scottish sides of the border, including the most notorious communities such as Liddesdale on the Scottish side, or in Bewcastle and surrounding villages on the English side, all of which were situated adjacent to long-disputed, lawless territory called the Debatable Lands, a region "lying between the Sark and the Esk as far up the latter as its junction with the Liddel" which was "conveniently situated for the resort of lawless men of both nations [who]...had become demoralised by the incessant Border warfare into nothing better than banditti."[31]

Routledge and Dacre

AD 1528, 28 February. Territories on both sides of the border were divided into three "Marches": east, middle, and west, with each March governed by an appointed Warden. The reiving families of Liddesdale (Scotland) and the Debatable Lands had grown so powerful as to be a law unto themselves. Most notorious among the reiving clans, the Armstrongs were reported able to raise a force of 3,000 armed English and Scottish followers, including some of the surname Routledge. Clearly, these night-riding raiders had lost all respect for feudal authority. Both English and Scottish regimes aimed to subdue them. At this time William Dacre, 3rd Baron Dacre, as Warden of the English West March, determined to take on the Liddesdale riders and their friends even though Liddesdale was not in his jurisdiction. Dacre reported on prisoners taken during a foray and lodged in Carlisle Castle. Notably, nicknames were commonly used to distinguish between close family members who shared the same given name: Dande Nicson, Clement's brother; John Nicson of the Maynes; Cristol Routlege, Lyon's son; James Routlege, Geo[rge] Routledge, Donned Rolland's son; Matho Lytell called Gutterholes; Peter Whithede; Davy Crawe. New made: Cristoll Nobill; Jok Nikson, called Deif Jok.[32]

AD 1528, 25 May. After a series of retaliation and revenge forays perpetrated by Armstrong cohorts, deputy Warden Christopher Dacre led a failed attempt at destroying Scottish Routledges, called "Qwyskes." As described by Elizabeth Dacre in a letter to her husband, Lord Dacre, by the time the English officers arrived, the Routleges had already departed to the wilds of Terras "in the uttermost part of the Debateable Ground." They could not be overtaken "by reason of the great strength of the woods and mosses." Nevertheless, Dacre took away "four-score head of nolt, five-score sheep and forty gate [goats], and returning burnt the houses of Black Joke's sons upon the Mere burn adjoining the side of Lidisdale."[33]

AD 1530s. England's King Henry VIII, having found himself without a male heir to the throne after 23 years married to Katherine of Aragon, determined to divorce her and marry the ill-fated Anne Boleyn—the second of Henry's six wives. To gain this end, he defied the Church of Rome, declared himself head of a reformed Church of England and set about the dissolution of Catholic monasteries, thus inspiring much alarm among his predominantly Catholic northern counties. From Yorkshire to Cumberland, thousands of rebellious noblemen and commoners joined in a popular uprising called Pilgrimage of Grace in October 1536. Loyalist and rebel clashes ensued across the land, adding to tensions exacerbated by successive bad harvests, rising grain prices, complaints between landlords and tenants, and an assortment of nasty family feuds. With the quelling of the uprising, many rebels faced execution.

AD 1537. Whether or not William Routlege and his son Thomas "of Lukkyns de Levyn" were rebel supporters or merely engaging in typical reiver activities against their old persecutor, Lord Dacre, is not clear. But on the 7th of June, they along with "Will Armstrang alias Willy Cut, Edm Armstrang his brother, Alan Forster alias Blontwod, John alias Jok Halidaye, John Graye" and up to 50 Scotsmen, attended a riot at "Hestedeheshe on the water of King" at Gilsland, a town in Lord Dacre's barony, located about 10 miles from Bewcastle. They were accused of attacking and murdering Thomas and John Crawe and Thomas junior for which they were indicted and tried for treason. On the 5th of October, William was acquitted but Thomas was found guilty and, presumably, ended his life on a hangman's rope or worse if the medieval punishment for treason were applied, that of hanging, disembowelling, drawing, and quartering.[34]

Routledge and Wharton

AD 1540s. The aging and increasingly tyrannical Henry VIII, in keeping with his Rough Wooing policies, issued instructions to his English March wardens to induce the riding surnames to the English side by bribery, coercion, or any means available—no matter which side of the border they lived on—the purpose being to weaken Scottish resolve to remain independent of England. And, it was evidently clear that rebels and outlaws fought for whichever side produced the right enticements. Thus, a duplicitous Thomas Wharton, 1st Baron Wharton, Warden of the English West March, wrote to his superior, Suffolk, (the English field commander) about recent "exploits" of his accomplice reivers, including one "Wille Routlege Ynglishman ande others Ynglish ande Scotismen to the nombre of xiiijt [16] persons" going to Jedworth Roxburgh where they burned the Abbot's corn and barn and then on going home the same night they burned more corn at a "graynge callid the Lard of Langlandes, as one Routleg namyd him."[35]

Of another exploit, the night of 2 November, Wharton wrote that "James Routledge, Davie Blakburn, and John Foster," with about 60 other English and Scotsmen burned the towns of "Sonnyside, Lathome, and Wowfferes," located on a stream called "Rowllie" on the Humes' lands. From there they took three horses and hurt [sundry] Scotsmen. Some of their own were also "hurt," but "none left behind."[36]

Scotland Complains of English Incursions

AD 1541. Cross-border raiding and posting of complaints were standard practice, with opposing wardens, injured parties, and accused reivers expected to attend truce days whereby complaints were filed, sureties and penalties were dutifully ordered and frequently ignored, all according to a set of rules that had evolved as border-law over the centuries.

Thir ar ane part of the slauchteris [slaughters] committit and done in the Myddle Marchis [central borders] sen the taking of the trewis [truce]...Complenis [complains] the lord of Fernieheist and his puir tennentis of Abbot Rowll [Abbot Rule], upon Don[ned] George Rowtleische, his brodir [brother], Jame Rowtleische, sone to Reyd Rolland, James Rowtleische [Englishmen] of the Todhoillis, Wille Grame callit [called] Will of the Belle, Mathew Frostar of the Dowhill, Cudde Graham, Dand Ellot, callit Baggott, Wille Grame, Arthuris maich, the Grame callit Ser, John Richartson, servand to Thomas Dacre, and thair fallowis, that thai cruellie slew Thome Oliver and Will Kowman.

Complenis Robene Scott of Alanehauch and his puir tennentis of Quhitchister, apon Jawfray Routleische, Blak Jok Rowtleische his sone, Ady Frostar of the Dowhill, Mathew Frostar his broder, Hobbis Robene Frostar, Wille Frostar his brodre, and their fallowis to the numer of fyfty men, that thai come to Quhitchistar, and thair brynt [burnt] and tuik away thre scoir ky [cow] and oxin, horss, meris, and insycht [furnishings], and presonaris [prisoners], again the vertu of the trewis, and breking of the Wardanis band maid at Expethgaitt...

Complenis Gynkeyn Armstrang, Niniane Armstrang, Archibald Armstrang, Berty Armstrang, Alexander Armstrang, Thome Noble, Quyntyne Rowtleisch, and thair nychtbowris [neighbours], Scottismen, apon Thomas Dacre, brodre to the Lord Dacre, and Wardane deput undir Schir Thomas Whairtoun, Wardane of the West Marchis of Ingland...and slew Andro Armstrang, as of befoir, tuik and drave away xx? of ky and oxin, xxx? Sheip, x? gait, j? swyne, xfj horse and meris, and udir guides...[37]

England Complains of Scottish Incursions

"Thomas Trumbull, George Rutherford, and other Scotishmen, to the nombre of anne hundreth men, comme to the baly in the realme of Inglond, and cruelly slewe and murdured John Routlege and Robert Nobill, Inglishmen... " Davy Pennango, and other Scotsmen, to the nombre of x personnes with hym, comme to a place in Gilleslande called Brome, and there cruelly slewe and murdured the wif of Andro Routlege, Englishwoman.[38]

Joke Routlege Swears Allegiance to England

AD 1543. King Henry VIII of England lost all patience in persuading the Scots to see value in uniting the two kingdoms. Scotland's "Auld Alliance" with France seemed to be gaining import as French soldiers and money arrived in Scotland. Finally, the death, in 1541, of Scotland's dowager Queen Margaret (Henry's sister) left no incentive for peace, and so began the wretched decade of "Rough Wooing" with Henry determined to subdue Scotland by force. Meanwhile, many Scottish reiving families, having become completely disenchanted with their feudal masters, decided to declare for the English faction. Numerous Armstrongs and one Joke Routlege went to Carlisle to take a solemn oath before Sir Thomas Wharton, in his capacity at that time as Captain of Carlisle Castle. They swore that they and their kin would "henceforth" serve the king of England and, as assurance of their loyalty, they "appointed sixteen persons to lie in pledge."[39]

Evidently, Wharton's superior, the Duke of Suffolk, had little faith in oaths made by Scotsmen:

Nowe of late I, the Duke of Suffolk, am advertised that the chief of the Armestranges, and of the Rowteleges, and the Nycsones of Lyddesdale, offred to Syr Thomas Wharton to serve the kinge with an hundreth horse men and an hundreth foote men, and to be sworne the kinges subjects and to dwell in Lyddesdale or in the Batable Ground or where the king will apointe theim in Englonde to dwell, so that they may have their frendes now beinge prisoners in the castles of Carlisle and Alnwik, who were takinge, robbinge and burninge in Englond, to be discharged and set at libertie, and also to put at libertie foure prisoners Englisshe men, which they toke at the burning of Sleyley, whan there kynnesmen were taken. Wherunto Syr Thomas Wharton, to whome they made this offre hath made none other aunswer but that he woll advertise the lorde warden therof, and so aftre make aunswer. Whereunto I have advised my said lorde warden to followe the same aunswer that hertofore hath bene given theim, whereby the Scottes shall not have occasion to saye that we have broken the treux in takinge to maytenaunce there subjectes breakers of the same treux. And besides that thies broken men be of that sorte that no promyse by them made dureth longer then it maketh for there purpose.[40]

AD 1550. Despite Suffolk's opinion of the loyalty of Scots reivers, the Liddesdale Routledges, at least, appear to have been sincere as, from this point on, history regards them as more English than Scottish. No doubt some of the surname Routledge continued living peacefully and without much notice in Scotland, with the exception of certain outlawed cohorts of the Liddesdale and Eskdale reivers, such as one Routledge called "tyn spede," who resided with George Armstrang called "Georgy gay with hym."[41]

AD 1561. While there had been no state-sponsored wars between the two countries since the so-called "Rough Wooing," border feuding continued to plague all attempts at civilizing the people whose very livelihood had so long depended on livestock rustling, protection rackets and hostage-taking. Such was the case on January 30, 1561 when a group of Scottish Elliots captured Thomas Routledge and turned him over to Sir John Kerr, lord of Fernieherst. Neither the underlying cause nor the final outcome of this event are clear but no doubt had something to do with cross-border reiving.[42]

Last of the Reiving Routledges of Scotland

AD 1569. With religious reformation well underway in both England and Scotland, Protestant versus Catholic clashes added religious zeal to civil breakdown among nobility and commoners alike. The reign of England's zealously Catholic Mary Tudor (1516-1558) had come and gone as had that of her Protestant half-brother, Edward VI (1537-1553), who died at the age of 16. Elizabeth I (1533-1603) , the last of the Tudor monarchs, held the throne of England. Elizabeth's cousin, Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587), a devout Catholic, had returned from France to assume her disastrous reign in Scotland. By 1569, she had been forced to abdicate and was on the run. Her Protestant half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (1530-1570), as Regent of Scotland, assembled a force supposedly to rid border communities of disorderly reivers, including those of the surname Routlaige. But more than one historian concluded that this cleanup foray was a thinly disguised excuse for retaliating against any border family that had rallied against the Protestant party to fight on the side of Queen Mary.[43]

. . .thirty-two of the principal barons, provosts, and bailies of towns, and other chief men, subscribed a band [bond] at Kelso, on the 6th April 1569. Representing the counties of Berwick, Roxburgh, Selkirk, and Peebles, they bound themselves to concur to resist the rebellious people of Liddesdale, Ewesdale, Eskdale, and Annandale, and especially all of the names of Armstrong, Elliot, Nixon, Liddel, Bateson, Thompson, Irving, Bell, Johnston, Glendonyng, Routlaige, Henderson, and Scotts of Ewesdale. Further, they undertook that they would not intercommune with any of them, nor suffer any meat, drink, or victuals to be bought or carried to them nor suffer them to resort to markets or trysts within the bounds, nor permit them to pasture their flocks or abide upon any lands 'outwith Liddesdale,' unless within eight days they should find sufficient and responsible sureties. 'And all others not finding sureties within said space, we shall pursue to the death with fire and sword, and all other kinds of hostility.'. . . signed [by] Lord Home, Walter Ker of Cessford, Thomas Ker of Fernihirst, and Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch. NOTE: Printed in Pitcairn's Criminal Trials, from the Original in H.M. General Register House, Edinburgh.[44]

Routledge and Musgrave

Routledges had been living in England since the 1480s, having been awarded land at Bewcastle Cumberland in exchange for military service to King Richard III of England. There they remained and proliferated as tenants of the English crown while gradually spreading to other parts of England. Accordingly with their expected military duty, many Routledge men proved themselves ready and willing to bear arms under the command of the Musgraves of Eden Hall, a family of ancient lineage whose men were "trained in service for defence of Her Majesty's poor people."[45] A succession of Musgrave men served as captains or constables of Bewcastle during the 16th to early 17th centuries. The Musgraves and Routledges alike were born and bred to take up arms. Evidence that the sword topped the Routledge sense of duty and pride is displayed on most of their gravestones extant from that era.

Routledge [arms] are found at Bewcastle and Stapleton. All the shields...bear or are intended to bear a chevron between a garb and a sprig of willow, and in chief a sword fessways.[47]

Routledge, Musgrave, Dacre

AD 1534. In those turbulent times, it was the legal duty of officials to raise a "hot trod" posse to pursue raiders, and, furthermore, it was the duty of all men within hearing of the alarm to respond. According to Sir William Musgrave, nothing of the sort had happened when, in 1534, a band of Scots from Liddesdale murdered one John Rutlage, a liegeman of Musgrave, without William Dacre, Warden of the English West March, taking reprisals against the perpetrators. Incensed, Musgrave formally accused Dacre with treasonous activities and dereliction of duty. Musgrave claimed Dacre had "machinated" that he, Sir William Musgrave and "all his tenants, might be slain by the Scots, and their houses and chattels destroyed." Dacre was indicted, tried, and subsequently acquitted.[48]

Routledge, Musgrave and the Battle of Solway Moss

AD 1542. The reign of James V of Scotland came to a sorry end shortly after a devastating defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss wherein a Scottish army of some 15-20,000 invaded England's West March and was thoroughly beaten and routed by a hastily assembled English force of 3,000 light horsemen. Many Scots noblemen were taken hostage. A jubilant Sir Thomas Wharton wrote a lengthy letter to Henry VIII triumphantly listing the prisoners to be held for ransom, including the "Earl of Cassill who Batill Routlege has taken, though John Musgrave claimeth a part for the loan of his horse to the said Routlege."[49]

Routledge, Musgrave and Cross-Border Connections

AD 1583. Throughout their tenure at Bewcastle, Musgraves were frequently engaged in self-serving and controversial disputes with other English border officials such as certain persons of the Dacre, Carleton, and Graham families. In 1583, Sir Simon Musgrave, wrote to Queen Elizabeth's principal secretary, Francis Walsingham:

I am sore trobled and put in great danger of my lyf by the disordered Graymes [Grahams] and the envious Carletons, who seek my lyfe and lyvinge both by false and untrue dealing and by confederating with Scotishmen to murder me and my son Thomas who, being in Scotland to take revenge of injuries done to the office of Bewcastle. . .was assaulted in English ground by Arthur Grayme and his accomplices to the number of 100 English men and Scottish men. . .[and by] a jury of their own men and appointment of Thomas Carleton. . .found my son guilty of willful murder [and also] forty of my servants.[50]

Contrarily, in 1583, Francis Graham petitioned the same Walsingham complaining that Sir Simon Musgrave and his son Thomas had taken away 160 cows and oxen, and during that fray Thomas had "murdered" one Arthur Graham.

Quite likely Routledge men stood alongside Musgraves in these quarrels as well as partaking in hot-trod reprisals against the Armstrongs, Elliots, Grahams, and other notorious English and Scottish reivers. On one occasion, Sir Simon Musgrave wrote to a friend explaining that his son Christopher had rounded up four notable Armstrong thieves and delivered them to "Her Majesty's gaol at Carlisle where three of them were executed." Since then, Musgrave concluded:

the friends of the said prisoners, to the number of 400 men, have confederated themselves against me, my friends and children, to run upon us with fire and sword, and have put the same in proof by spoiling a man of mine named George Rowtledge. . .This attempt has put all the inhabitants of Cumberland in great fear, for the like has not been done since I was born.[51]

AD 1583. Desperate that the powers in London might understand the difficulties facing him and his under officers, Thomas Musgrave, as Deputy Captain of Bewcastle, wrote to one of Queen Elizabeth's chief counsellors, William Cecil 1st Baron Burghley. First, Musgrave complained that in his official capacity he had endured not only "the loss of my blood and many troblesome travels and dangers, but [also] the loss of my dear frends and companyons which have been cruelly murdered by the rebellious Scottes." Musgrave then followed his opening remarks with complete descriptions of the "riders and ill doers both of England and Scotland," including the "names, dwellynges, and allyaunces" of every family living along the rivers Lydall, Eske, Sarke, and their small tributaries as they proceed to the sea from Scotland to England, including many of the surname Routledge.

. . .John Rutledge of the Cructborne slayne by Scottish riders, Gerry his son; Adam Rutledge of the Netclugh, Anton Rutledge and Andrew Rutledge of the same; Dikes Rowe Rutledge; Jeme Rutledge of the Neuk; Jeme Rutledge of the Baley Head, Thom Rutledge of the same. All these dwell in a place called the Bale, within the Fosters. More Rutlidges dwell down the water of Leven, John Ruttlidge of the Black Dobs, Nicoll Rutlidge his brother; Andrew Rutlidge called Black stafe; Gourthe Rutledge of Sletbeke, Jeme Rutlidge of the same; Will Rutlidge of Comerauke, Riche, John, and Jeme of the same; John Ruttlidge of Troughed, Rich and John Rutlidge of the same, Allan Rutlidge his brother; Willi Rutledge of the Lukknes, and many more I omit for tedyousnes to your honor. . .John Rutlidge of Kemorflat, Will Rutlidge of Kyrkbekmouth dwell within the demayne of Bewcastell. More Rutliges live at the Belbank, namely Clem Rutlidge of the Kyll, Jenkin Rutlidge of Belbanke, Will Rutlidge of Nunsclughe, Gorth Rutlidge of Masthorne, these join upon Gilsland my lorde of Arrundalls land. How be it the furthest part of Lyddisdale and the furthest part of Bewcastell are not distance of xvj [16] miles so as the ryders may by night easily come to anie part of it, do their accustomed evil deeds, and be at their own howses long before daie; . . .Bewcastell goes to 'Souport' [Southport] belonging to William Musgrave where mostly Taylors live, except Will Rutlidge of the Lukins and Will Rutlidge of the Sinke Head.[52]

The Musgraves more or less adhered to a prevailing law of the day that prohibited,[53] except on licence, marriage between English and Scottish borderers. It was, Musgrave said, the entanglements of cross-border marriage alliances that made it near impossible to govern the "lawless" people. Such imposed legalities went largely ignored by many borderers, but evidently not so much by the "Ruttligis." Of the dozens of Scottish Armstrongs, Grahams, and others much aligned by English marriages, Musgrave names only one Routledge, that of Gourth Routlishe daughter of Shetbelt, married to Thome Armestronge of Chengles.

According to Musgrave, "the Ruttligis and their alleyance with Scotland is but little, for that they are every man's pray." While that curious statement is open to interpretation, it certainly supports the premise that the Routledges living in Cumberland England had, within the past fifty years, distanced themselves from their Scottish heritage and accepted Musgrave-style law and order. These Routledge families were prime targets for every passing Scottish foray partly because of their disdain of Scottish marriage alliances and partly because of their willingness to fight alongside their Musgrave commanders.

Routledge regard for the Musgrave family is further evidenced in three of five Routledge wills testated between 1597 and 1631, which were interpreted by J V Harrison and presented to the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society in 1967.

In his final will and testament, in 1597, John Rowtlidge of the Blackdubs entrusted his "master," Thomas Musgrave, captain of Bewcastle, with the task of collecting a debt owed by one Marmaduke Stavely. Furthermore, he entrusted Musgrave to be "umpear" [umpire] in case of any disputes to this will.

NOTE: That Rowtlidge loaned Stavely money suggests some sort of relationship between the two men. Stavely is recorded in a 1583 "brief abstract of the musters of light horsemen. . .in Beaucastell" as one of two "gentlemen deputies to Sir Symonde Musgrave," the second gentleman being John Musgrave.[54]

NOTE: A second relationship between Stavely and Routledge families is recorded in the parish registers of St Olave York or St Michael le Belfrey when Anne Stavely of York married Hector Rowtlidge on November 26, 1587.[55]

In his 1597 will, Rowland Rutledge of the Nook wrote about the marriage of his granddaughter Elizabeth Rutledge, that she "shall marrie when it pleaseth my maister Thomas Musgrave captain of Bewcastle."

In 1631, John Routledge of Dapleymoor made Edward Musgrave "supervisor" of his will because of the "good opinion I have."[56]

Mayhem Reigns Over Bewcastle

AD 1580s-1590. Lawlessness escalated and a sort of gangland justice prevailed. Criminal elements of larger clans terrorized more peaceful farmers with protection rackets, and officials went begging for help from England's Queen Elizabeth I and Scotland's James VI. Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton, as Warden of England's West March, wrote to Queen Elizabeth's secretary of the deplorable state of "Beaucastell" with many of "her Majestie's" tenants so "decayed by reason of great spoiles they have sustained by the Lyddisdails" that they were unable to arm themselves in her Majesty's service as was required. To which Burghley callously replied: "The Lord Scrope would be advised to charge all the Queen's tenants who are bound by their leases" and noncompliance would "void" their leases. "By this means the defaults would soon be repaired."[57]

The Calendar of Letters and Papers Borders of England and Scotland chronicles a litany of complaints that went well beyond the sporting activity of livestock rustling to outright mayhem. In 1582, John Rowtledg called Gerardes John was murdered as was Allan Rowtlege of Bewcastle. In 1583, William, Thom, and John Rowtledge were "maimed and hurt in peril of death, wherof one hath his leg cut off." Rowy and Dand Rowtlege of Bewcastle, Dick Rowtledge of Kirkleventon and his son were "maimed and wounded in peril of death." Even relatively defenceless widows were mercilessly targeted, including Margaret Forster, Hecky Noble, a Mrs Hetherington, and Isabell Routledge. One of only two Routledge females found thus far in the historic records, Isabell Routledge was attacked by thirty Elliots who made off with her only horse and six cows.[58]

In December 1583, four Routledge brothers, — George, Thomas, Andrew, and William — "dwellers in Bewcastledale," petitioned Walsingham:

for and in the name of all our neighbours of the barony of Bewcastle, that the Scotts to the number of one hundredth and an half rode a forrowe [foray] against us. . .and drove away from us, by force and hostility, four score head of cattle, and killed Allen Routlage our poor brother. Lorde Scrope, Warden of the Marches, willed us to inform your honour by this token — when you were upon the border that the bloody shirts were shewed — that your honour asked him what might be a fit remedy. And then the Lord Scrope said that soldiers in convenient places upon the border might help. . .May it please your honour to have consideration of your poor supplicants, for they, their wives, bairns [children] and neighbours are beggared and utterly cast away.[59]

AD 1588. Notoriously dubbed the "Bold Buccleuch" for his many daring exploits, Walter Scott, 1st Lord Scott of Buccleuch (1565-1611) mustered up 100 to 200 men and regularly crossed the border with Bewcastle in his sites, prompting English officials to record "Outrages by Buccleuch," two of which involved Routledges.

The captain of Bewcastle and the surnames of the Rowtledges, Nixsons, Nobles and others of Graistangflatt within the office of Bewcastle, complain upon Walter Scott laird of Buckclughe and his accomplices who ran a day foray and reft from them 200 kye and oxen, 300 sheep, and 'gait'.

Captain Steven Ellis and the surnames of the Rowtledges in Bewcastle, complain upon the laird of Bucklugh, the laird of Chesame, the young laird of Whithawghe, and their accomplices to the number of 120 horsemen 'arrayed with jackes, steel caps, spears, guns, lances, swords, and daggers,' purposely mustered by Bucklugh, who broke the house of Wille Rowtledge, took 40 kye and oxen, 20 horse and mears, and also laid an ambush to slay the soldiers and others who should follow the fray, whereby they cruelly slew and murdered Mr Rowden, Nichel Tweddell, Jeffray Nartbie, and Edward Stainton, soldiers, maimed sundry others, and drove 12 horse and meares, whereof they crave redress.[60]

Beginning of the End of Reiving Years

AD 1580. According to muster rolls taken in 1580, Routledge men were living and "fit for service" in both the West and East Marches of England. In Cumberland, Mathew and John Rowtledge lived in Askerton Lordshippe; Randell Reutledge lived in Lannercost; Thomas, Andrew, and William Reutledge lived in "Watton Parish;" and Lancelote Reutledge lived in Skailby. In 1584, John, Christofer, Thomas, and Rigmone Rutliche were found to be "effective men" living in Kilham, a village in Northumberland located near the border of Roxburghshire Scotland. Many other Routledge men went uncounted in the more unruly districts because, as the officials recorded, the "inhabitants within Eske, Leven, Bewcastell, and Kirklinton" did not muster-up.[61]

AD 1593. A delegation headed by the Earl of Huntington reported on managing and subduing the "bad and most vagrant sort of the great surnames of the borders":

namely, of the Grames, Armstrongs, Fosters, Bells, Nixons, Hethertons, Taylors, Rootlidges with other very insolent members appertaining to them. . .His lordship concluded with himself to call the principal and chief of every branch. . .and to constrain them to enter bond in good security for their own appearance before him when called upon. . .and to make answerable for any matter to be laid to their charge. . .[whosoever refuses] the lord of the manor where the transgressor dwelleth shall. . .seize the tenement and shall utterly expel and put out from the same the wife, children, servants, and friends of the offender.[62]

AD 1595. Again, a plea for help with John and James Rutledge complaining for themselves and other tenants of Bewcastle of the spoils and oppressions committed against them by the Scots, and Lord Scrope unable to defend them for lack of soldiers.[63]

AD 1596. A deadly feud broke out between East March inhabitants of Kilham Northumberland and underlings of Sir Robert Kerr of Roxburghshire. According to "Cessford's Roll of Wrongs," Ninian Rowtlage and Jame Rutledge were among others accused of pillaging the "Guidman of Gaitschaw" and taking "10 score ewes and wodders." In retribution, 15 Davison cohorts went to Kilham and cruelly slew Renian Routledge in the field while he was loading hay, "giving him 20 wounds, and not leaving him till dead." [64]

AD 1599. As the 16th century and Queen Elizabeth's reign drew to a close, and with Scotland's James VI expecting to inherit her realm, life on the borders went on in the usual tit-for-tat revenge reprisals. Various commissioners and wardens tried, with little if any success, to impose "redress" for decades-old bills and countless grievances. In 1596, as if exasperated with all previous attempts to aid the Queen's tenants at Bewcastle, her Privy Council wrote to Thomas Musgrave offering their only advice, to which Musgrave replied: "I received your letter, that if no justice could be had otherwise, I might recover the worth of their goods as I can. Whereon with my kinsmen and friends, I took from John Armstrong of the Hollus, 'the leder of these incurcions, somme vj [six] or vij [seven] score of cattill [cattle]."[65]

While the records quoted thus far in this article may imply that the Routledges and other borderers on the English side were worsted by their Scottish counterparts, a more complete, unbiased, account would imply a rather different story. The evidence is found in a 1593 letter written by West March Warden Scrope to Queen Elizabeth's secretary Burghley. The letter includes a tally of monetary redress demanded by the English West March against the Scottish West March and Liddesdale. Whereas England wanted a total of £9,700, Scotland wanted £41,600. So, Scrope concludes, England was to "answer for" £32,000 more than the Scots. Even assuming gross exaggeration, the figures clearly show that the inhabitants of Liddesdale and the Scottish West March suffered much more than their Bewcastle counterparts.[66]

Routledge in the 17th Century

In 1603 England's Queen Elizabeth I died without issue and her cousin James VI of Scotland became James I (1566-1625) of both Scotland and England. Determined to unite the two countries and rid the borders of unlawful activities, James had it proclaimed that, with the exception of "noblemen and gentlemen unsuspected of felony or theft," border inhabitants "shall put away all jacks, spears, lances, swords, daggers, steelcaps, hagbuts, pistols, plate sleeves, and such like - and shall not keep any horse, gelding, or mare, above the price of 50 sterling. . .upon pain of imprisonment."[67]

Routledge on the Move

Church of England records show that some border surnames had tired of the reiving way of life long before the dawning of the 17th century. Routledge families were certainly among those who searched for land and peace away from border strife by the mid-1500s. Numerous baptisms, marriages, and burials are recorded by parish vicars all over southern Britain, albeit with the outlandish spellings typical of the era but nonetheless bearing some proximity to Rutledge or Routledge. Perhaps the earliest available baptismal record is for a Humphrey Rettleg christened in Staffordshire England in 1516.[68]

Many notorious border surnames sought refuge as yeoman tenants on manors near the city of York while others set up trades. Johannes Rowtleache, in 1585, married Alicia Gawthrop at Saint Olave church, York. Their son Georgius Routledge was baptized there in 1589.[69] Quite likely this father and son pair of milners [hat makers] were the same men admitted later on to the "Freedom of York" and thereby allowed to practice trade within city limits. Johannes Rutledge was admitted in 1607 and Georgius Routledge was admitted later on in 1640. Preceding these two were Hector Rowtlidge, a tailor, who had been admitted in 1584, and Edwardus Rutleedge, also a tailor, admitted in 1604.[70]

AD 1605-1625. Unifying Scotland and Britain would take decades to accomplish, and reiving activities continued to plague the newly-termed "middle shires" despite every attempt to pacify truculent borderers and eliminate a way of life inbred during three previous centuries of sporadic warfare and associated depredations. In 1605 Thomas Routledge alias Bailiehead of Bewcastle, was on the move, hiding out from local authorities and evidently clinging to the old ways as he was included among the more unruly types that warranted close attention "for the bettering of his majesty's service." A local garrison occupied Thomas' house until such time he made himself "answerable to his majesty's laws."[71]

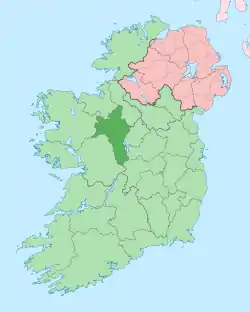

In 1606, border authorities hatched a scheme to rid the country of the worst malefactors by transporting them to the Plantation of Ulster, a British colony in Northern Ireland seized from Irish owners after the Nine Years' War. Most of the colonists came from England and Scotland, some of them having been forced to settle there. The Grahams of Cumberland were especially targeted for transportation, along with other "dangerous" reivers. The Bishop of Carlisle, writing to the Earl of Salisbury in 1606, stated that the Routledges, "have been as offensive as the Grames [sic] though not so powerful."[72]

Meanwhile, for those remaining on the English, Scottish borders, life went on as precariously as ever. Thompson's-Walls, Northumberland was a typical farming hamlet near Kilham and the Scottish border where a "sudden quarrel" ended violently for Lancelot Routledge. Fortunately for Lancelot, he received a pardon for "manslaughter" on March 22, 1615. Nothing is said of the victim.[73]

In Scotland, one Robert Routledge of Thorlieshope, a farm located in Newcastleton Roxburghshire [Liddesdale], appears in a long list of free-spirited troublemakers called to the Jedburgh Circuit Court in April 1623, and having not appeared, all were publicly declared "thrie several tymis, outlawis and fugitives.".[74]

Routledge and the Colonial Era

Colonizing the east coastal regions of North America and offshore islands from Newfoundland to the Caribbean (West Indies) had been underway ever since explorers Christopher Columbus and John Cabot set sight of land in 1492 and 1497 respectively. During the 1600s, thousands left their European homelands for life in the New World. They came from all classes of society: from younger sons of the nobility seeking their own fortunes, to religious dissenters, to adventurous opportunists, to unfortunates such as prisoners-of-war and common criminals who were transported into indentured service.

AD 1635. According to a document covering various lists of Britains who went to American plantations between 1600-1700, there was, in July 1635, a Jo Rowlidge, age of 19, among 64 men and 11 women sailing from London to "Virginea" aboard the ship Merchant's Hope, upon having taken oath "touching their conformitie to the Church discipline of England."[75]

AD 1625-1649. These years cover the disastrous reign of Charles I (1600-1649) of England, Scotland, and Ireland, yet another of the Stewart line whose rule ended unhappily. A steadfast believer in the divine rights of kings, Charles sought to assert his authority against the power of Parliament while religious reformers of conflicting views, such as the English Puritans and Scottish Covenanters, brought Protestant and Catholic differences to a head. Political and religious turmoil led to the English Civil War (1642-1651) between monarchists and parliamentarians, and Charles' eventual beheading in 1649.

In 1624, a John Rutledge was "Keeper of the North Park, Hampton Court,"[76] a magnificent royal palace located on the River Thames about 12 miles from London. Perhaps this was the same man acquainted with Sir Allen Apsley, a prominent courtier of the day who, as Lieutenant of the Tower of London in 1626, recommended a John Rutlege for an appointment as Purser of the St Mary.[77] Incidentally, Apsley was also one of the founders of the New England Company,[78] which begs the unanswered question of whether or not a Rutledge was among the first colonizers of New England. Later on, in 1629, a John Rutlish, "purser of the St Mary," found himself arrested by the bailiff of the liberty of St Katharine's [a precinct near the Tower of London] while doing the king's business of "victualling the St Claude out of his own purse," despite having produced a warrant by the Duke of Buckingham testifying that Rutlege was "his Majesty's servant." Rutlege's petition "prays for payment of 59 pounds and discharge from arrest."[79] Both the St Mary and the St Claude appear in a List of early warships of the English navy as having been captured from the French fleet.

Routledge and Cromwell − the Commonwealth Era

AD 1642 to 1659. Civil war raged across Britain. By 1648, the so-called United Kingdom was on the brink of devastation what with religious extremists and troops loyal either to the royalists or to the parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell spreading terror across all of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Carlisle, the western gateway city to border counties, surrendered to Cromwell in October 1648, and a garrison of foot and horse was established there for "suppressing the insurrections of Moss-troopers" who might take advantage of the unrest to resort to criminal activities that had formerly plagued border regions for centuries past.[80]

AD 1649. A list of Irish-born officers, known as the "49ers," who had served in English armies before the 5th day of June 1649, was assembled for adjudication of their claims for unpaid arrears. Included were a Lieutenant Edward Rutledge and a Thomas Rutlidge.[81]

Parliamentary forces prevailed in 1651, and Oliver Cromwell assumed government of the Commonwealth of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland under the title of Lord Protector until his death in 1658. His son, Richard Cromwell (1658-1659) succeeded his father's position for less than a year and willingly stepped down in 1659.

AD 1652. Some soldiers who had served the Commonwealth in Ireland were promised land in lieu of pay, and names of those who qualified were duly recorded during earlier Cromwellian Settlements. A Francis Rowlidg claimed land in counties Meath and Kilkenny. Nicholas Rutleidge made a claim in county Sligo, and Thomas Rutlidge claimed land in Tipperary. Nicholas and Thomas subsequently appeared in a list of grants made under the Acts of Settlement (1652) and Explanation (1666), enacted during the Restoration reign of King Charles II.[82]

AD 1660-1685. British politicians and civilians soon tired of a republican government dominated by Puritan moral strictures. After the downfall of the Cromwell Protectorate it was decided to revert to a monarchy system, and Charles Stuart (1630-1685) returned from exile in mainland Europe to reclaim the crown as Charles II. Parliament forced him to reestablish the Church of England as the primary religion, although he preferred religious tolerance, and he also pardoned all past treasons against the crown with the exception of the 59 commissioners who had signed his father's (Charles I) death warrant in 1649.

Rutlish School for Boys

AD 1670-1687. The village of Merton, located about 9 miles from London, is home to a 12th century parish church dedicated to St Mary. In the church-yard is the tomb of William Rutlish (1605-1687) who held the post of embroiderer to Charles II.[83] Rutlish was one of three embroiderers appointed along with George Pinckney and Edmund Harrison. These gentlemen appear in Treasury and State Papers in a variety of ways. Rutlish and Pinckney had a long-standing "patent" dispute with Harrison, which eventually resolved when Harrison "surrendered" to Rutlish and Pinckney.[84]

Rutlish and Pinckney were listed in Loans into the Exchequer as having loaned the government money towards British war efforts, likely against France. A Treasury order for "£247, 10 shillings," dated 1670, was entered with "repayment of the loan to be registered on the fee farms with only 6 percent interest."[85] Evidently, getting repaid for services rendered sometimes required legal action as shown in a petition for £680, 16 shillings as presented by "one Applegarth, Rutlish's solicitor."[86]

William Rutlish died in 1687 leaving £400 for "apprenticing poor children," in part to be used for schooling and part to be "distributed in clothes, bread and coals." That legacy eventually grew sufficiently to support a school and, over succeeding centuries, the Rutlish School became one of the foremost educational institutions in England.[87]

Routledge in the 18th Century

Routledge and the Jacobite Era

AD 1686-1701. Charles II died in 1685, and his brother received the crown as James II of England and Ireland. Scotland preferred the title of James VII of Scotland, exemplifying the ever precarious state of religious and political affairs within the United Kingdom. James II espoused tolerance of non-conformist Protestants as well as Roman Catholics, but war with Catholic France was on the horizon. Suspected of being pro-Catholic and pro-France, James soon got on a collision course not only with England's political elites but also with his own daughter, Princess Mary (1662-1694). Mary who had been raised Anglican married a Dutch Protestant, William Prince of Orange. Parliament invited William to bring an invasion force to English shores; thereupon James II fled to France where he died in 1701 having only once attempted to regain the crown. In 1690, with French assistance, James launched a war in Ireland but was defeated by William, now William III of England, at the Battle of the Boyne.

The Church of England regained the upper hand in Great Britain under the reign of Mary II and William III with the Act of Settlement 1701 proclaiming that only Protestants could ascend the joint thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Nevertheless, Catholic sympathisers called Jacobites championed the Stuart cause for the next half-century. James Rutledge and son Walter would play significant parts in those Jacobite uprisings.[88] After Mary II died in 1694, William ruled alone until his death in 1702 and then Mary's sister Anne, also a Protestant, inherited the crown. Queen Anne had married her second cousin George of Hanover who, as her closest living Protestant relative, inherited the British crown upon Anne's death in 1714. George I held the crown until 1727 when it passed to his son George II who had it until 1760. All the while, Stuart descendants of James II lingered in exile conspiring for any opportunity to reestablish a Stuart dynasty.

AD 1701. Aside from exiled royalty and their supporters, many persecuted religious dissenters, such as the Quakers, left Britain in the hopes of finding tolerance elsewhere. In Five Bewcastle Wills, Harrison wrote that, in 1677, "Thomas Routledge of 'Toddels' was presented as a Quaker by the rector and churchwardens of Bewcastle."[89] Perhaps this Thomas or his descendants were among the first of the Society of Friends recruited to colonize Quaker settlements in Pennsylvania, which had been established by William Penn (1644-1718) in the mid-1600s. The earliest Routledge record found to date in Pennsylvania is the marriage between John Routledge and Margaret Dalton celebrated on May 9, 1701, at the Fallsington Friends Meeting.[90] Formed in 1683, the "Falls Meeting was the first religious organization in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.[91]

AD 1708-1719. James Francis Edward Stuart (1688-1766), the son of James II, carried on the Stuart cause in exile. His Jacobite friends styled him as King James III of England and VIII of Scotland while British loyalists nicknamed him the Old Pretender. Aided by sympathisers in Britain plus a large contingent of dispossessed Irish exiles who joined and fought for Irish Brigades in France and Spain, he led several unsuccessful French and Spanish-backed invasions of Britain via Scotland. Among those dispossessed Irishmen, James Rutledge was a Jacobite supporter who left Ireland and established himself in France after losing property during the Williamite confiscations.[92]

AD 1713-1714. On the loyalist side, a Captain Rutlidge served with English forces and died under the command of Major General Thomas Whetham. By this time, Wetham had led campaigns in Scotland, West Indies, and Spain, so it is likely Rutlidge died while on duty during one of those conflicts. The Captain's first name is not recorded, rather "Declared Accounts" for this period state that the Captain's wife Anne Rutlidge received a widow's pension of £26 per annum.[93]

AD 1743-1746. This period chronicles the efforts of Charles Edward Stuart (1720-1788), popularized in history and folklore as Bonnie Prince Charlie. He was born and raised in exile in Rome but at age 23 went to France to renew Jacobite support for another French-backed invasion intended to restore a Stuart monarchy in England, Scotland, and Ireland. In France, Charles met with two wealthy merchants and privateers: Antony Walsh of Nantes, and Walter Rutlidge of Dunkirk.[94] These expat Irishmen outfitted two ships from which Charles could launch the invasion: the Elisabeth, a 66-gun man-of-war to accompany the Doutelle, a 14-gun privateer with Charles and friends on board. The Doutelle successfully landed at Eriskay Scotland on 23 July 1745. After some early successes in Scotland and England, the last significant Jacobite rebellion culminated in a crushing rout at the Battle of Culloden on April 16, 1746.[95][96]

Routledge and the British Empire

AD 1750s-1800. International conflicts between rival European powers escalated for domination of overseas trade routes and colonization rights across the globe from Africa to Asia, Australia, and the Americas where certain Rutledge families had, by this time, already become prominent in colonial affairs. Increased colonization led to a British Empire that would soon encircle the globe. Unprecedented opportunities for adventure and wealth would send thousands upon thousands to far-flung corners of the world, even for some at the bottom of society who went abroad against their will.

AD 1765. Convicted of "horse-stealing at the city of York, Richard Routledge was imprisoned and sentenced to death" but then he received respite via 14 years' transportation.[97]

AD 1770. Thomas Rutledge was tried, convicted for stealing, and confined at the Old Bailey prison awaiting transportation for 7 years when he received a pardon to serve on a ship of war.[98]

Meanwhile, as the first rumblings of the steam-powered Industrial Revolution began making noise across the land, the reiving way of life fell into folk story and legend while its former adherents pursued legal livings in every sort of new-age craft and profession in every part of Great Britain. A census taken in 1800 recorded Routledge and Rutledge families living in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Massachusetts, New York as well as in the Carolinas and with the usual variety of odd spellings such as Ratledge, Ruttidge, Rudleage, and Ruthlidge.[99]

Routledge and the Carolinas

AD 1663. Britain's Charles I had, in 1629, created the Province of Carolina in territory comprising what is now North and South Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia. His successor, Charles II, regranted the land to eight royalist gentlemen who had helped him regain the crown in 1660. Known as Lords Proprietor, these men were to establish a class society similar to that of England: aristocrats owned huge tracts of land tenanted out to farmers who held heritable, tradeable, and sellable rights to their plantations. Farming families would work the land, helped by indentured labourers and, increasingly, by slaves imported from Africa either directly or via other colonies in the West Indies. It is not known exactly when a Routledge first landed in Carolina but within the next 100 years the Rutledges of South Carolina would be among the leaders of a new nation.

AD 1677. Small-hold planters having been squeezed out of Barbados moved to Carolina. It is not known if Routledge families were among those Barbadian emigres, but it is certain that a Katharine Rutlidge lived on the island of Barbados during that era because Church of England records indicate that she married Hugh Kenna there in 1677.[100]

AD 1729. Disputes between the Lords Proprietor and Carolina citizens led to the Province reverting to a crown colony in 1719, and by 1729 it was split in two – North Carolina and South Carolina, with each colony to be governed by a crown-appointed Governor and a House of Commons. Robert Johnson (1682-1735) was appointed Royal Governor of South Carolina. He is credited with having devised a plan for settling the interior with "poor European Protestants" upon land divided into 10 townships. By 1735 "nine townships had been surveyed and hundreds of Irish, Swiss, German, and Welsh settlers had immigrated into six of them."[101]

Andrew Rutledge (1706-1755)

AD 1733. Not everyone in the prosperous colony of South Carolina approved of Johnson's land distribution scheme. A "Mr Frewin" felt compelled to write to the Council of Trade and Plantations on behalf of certain land developers about "several strange resolves and ordinances of the Upper and Lower Houses of Assembly." Claiming that the "wealthy merchants and principal inhabitants" were put at the "mercy of a few. . .in power here," Frewin wrote that the Chief Justice [Wright] and all the lawyers in the Province were opposed to recent enactments, "except the present Attorney General and Mr Rutlidge his Excellency's [Johnson's] Prime Minister." The "Mr Rutlidge" mentioned is presumed to have been Andrew Rutledge, the first of the Rutledge surname recorded in South Carolina. In 1733, Rutledge was elected to the Commons House of Assembly wherein he proved himself a champion of commons power as attested above by Mr Frewin's indignant letter, which further claimed that the offensive legalities were purely "a creature of Rutledge's brain."[102]

Rutledge may have arrived in South Carolina shortly after graduating from Middle Temple, London (Inns of Court) where he was admitted to study British law in 1725/6. The Register of Admissions states as follows: "February 1, Andrew Rutledge, son and heir of Thomas R, late of Callan, County Kilkenny Ireland, esq, dec'd [deceased],"[103]

The first notice of Andrew Rutledge's career in public service is his name on a commemorative plaque serving, in 1731, as Deputy Surveyor General. Other records have him serving, at various times, as adjutant general of the militia; as Justice of Peace, and as Christ Church Warden.[104] From 1749-1752, he was Speaker of the Commons House of Assembly.[105]

AD 1739. The land distribution views of both Johnson and Rutledge coincided with those of philanthropist James Edward Oglethorpe (1696-1785) and his group of 114 colonists who anchored in Charleston in January 1733, having sailed from Gravesend England aboard the ship Anne with a mandate to found a colony for the "worthy poor" in what is now the State of Georgia. Certainly, James Oglethorpe thought highly of Andrew Rutledge. In 1739, when the post of Chief Justice became available, Oglethorpe wrote to the authorities in England, recommending Rutledge for the position. To the Duke of Newcastle, Oglethorpe wrote:

I take the liberty of laying before you that Andrew Rutledge, who was bred to the study of law in England, is a very worthy and deserving man; that he hath acquired a very great character in Carolina; and that he is distinguished by his zeal to His Majesty's person and government. And I should have thought myself very wanting in justice to the public as well as to him if I had not acquainted you with his merits since I know you will interest yourself for the person who is most capable of executing so great a trust.[106]

Dr John Rutledge (c 1713-1750)

Andrew's brother, known as Dr John Rutledge, also immigrated to South Carolina during the 1730s and distinguished himself in public affairs. He served as surgeon to the Charleston Militia in 1738, as vestryman for Christ Church Parish 1745-1750; and from 1745-1750 was the legislative representative, first for St Paul's Parish and then Christ Church Parish. Both men had married into the wealthy Hext family, Andrew to Sarah Boone Hext in 1735, and in 1738 Dr John married Andrew's stepdaughter Sarah. That marriage produced 7 children: John in 1739; Andrew 1740; Thomas 1741; Sarah 1742; Hugh 1745; Mary 1747; Edward 1749. Three of Dr John's sons followed their uncle Andrew's lead and studied law at the Middle Temple: John Rutledge in 1754, Hugh Rutledge in 1765, and Edward Rutledge in 1767,[107] while Andrew and Thomas went into business. Dr John died in 1750, when his eldest son, John, was only 11.[108] In succeeding decades, many of Dr John's descendants would become prominent in social and political circles, not only in South Carolina but also in a new country yet to be named the United States of America.

John Rutledge 1739-1800

.jpg.webp)

John Rutledge, the eldest son of Dr John Rutledge and Sarah Hext, studied law at the Inns of Court in England and, in 1761, followed his father and uncle as a representative in the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly. In 1764, Rutledge was appointed Attorney General of South Carolina and actively participated in the American Independence movement (1765-1783). He was the youngest delegate to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, which petitioned King George III for repeal of the Act, and he was in charge as President (1778) and then Governor of South Carolina (1779) when the British attacked Charleston and took control of the entire state of South Carolina (1780-1782). After the war, in 1787, Rutledge headed the South Carolina delegation to the Constitutional Convention and, as chairman of the Committee of Detail, presided over the writing of the first draft. The following year, he was a member of the South Carolina Ratification Convention. On September 24, 1789, President George Washington nominated Rutledge as one of the original Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, a post he resigned in 1791 to become Chief Justice of South Carolina’s highest court. Again, in 1795, Washington nominated Rutledge, this time as Chief Justice of the United States. He served in that position as a recess appointee for four months, pending approval by the Senate.[109] In the interim, Rutledge gave a speech in Charleston vehemently denouncing the Jay Treaty (a highly controversial document meant to redress issues with Britain since the American Revolutionary War), thereby putting himself in the middle of a political maelstrom between Federalists led by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson's Republicans. Despite President Washington's continued support, the Senate refused to confirm Rutledge's appointment by a vote of 10 to 4, a defeat that more or less ended his otherwise exemplary career in public service.[110][111]