French Revolution

The French Revolution (French: Révolution française [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ fʁɑ̃sɛːz]) began in May 1789 when the Ancien Régime was abolished in favour of a constitutional monarchy. Its replacement in September 1792 by the First French Republic led to the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793 and an extended period of political turmoil. This culminated in the appointment of Napoleon as First Consul in November 1799, which is generally taken as its end point. Many of its principles are now considered fundamental aspects of modern liberal democracy.[1]

| Part of the Atlantic Revolutions | |

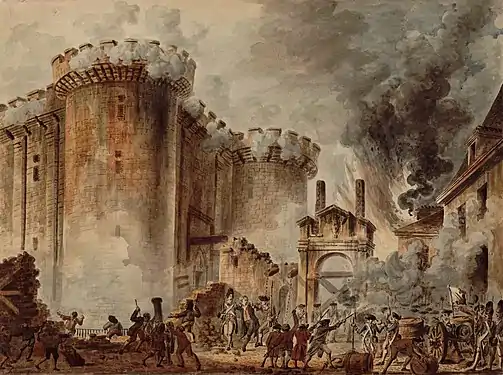

The Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789 | |

| Date | 5 May 1789 – 9 November 1799 (10 years, 6 months and 4 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Kingdom of France |

| Outcome |

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of France |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Monarchy |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Politics portal |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

| Politics portal |

Between 1700 and 1789, the French population increased from 18 million to 26 million, leading to large numbers of unemployed, accompanied by sharp increases in food prices caused by years of bad harvests.[2] Widespread social distress led to the convocation of the Estates General in May 1789, the first since 1614. In June, the Estates were converted into a National Assembly, which swept away the existing establishment in a series of radical measures. These included the abolition of feudalism, state control of the Catholic Church and extending the right to vote.

The next three years were dominated by the struggle for political control, exacerbated by economic depression and social unrest. External powers like Austria, Britain and Prussia viewed the Revolution as a threat, leading to the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in April 1792. Disillusionment with Louis XVI led to the establishment of the First French Republic on 22 September 1792, followed by his execution in January 1793. In June, an uprising in Paris replaced the Girondins who dominated the Assembly with the Committee of Public Safety under Maximilien Robespierre.

This sparked the Reign of Terror, an attempt to eradicate alleged "counter-revolutionaries"; by the time it ended in July 1794, over 16,600 had been executed in Paris and the provinces. As well as external enemies, the Republic faced a series of internal Royalist and Jacobin revolts; in order to deal with these, the Directory took power in November 1795. Despite military success, the cost of the war led to economic stagnation and internal divisions, and in November 1799, the Directory was replaced by the Consulate. This is generally viewed as marking the end of the Revolutionary period.

Many Revolutionary symbols such as La Marseillaise and phrases like Liberté, égalité, fraternité reappeared in other revolts, such as the 1917 Russian Revolution.[3] Over the next two centuries, its key principles like equality would inspire campaigns for the abolition of slavery and universal suffrage.[4] Its values and institutions dominate French politics to this day, and many historians regard the Revolution as one of the most important events in human history.[5]

Causes

%252C_rev%C3%AAtu_du_grand_costume_royal_en_1779_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Historians generally view the underlying causes of the French Revolution as driven by the failure of the Ancien Régime to respond to increasing social and economic inequality. Rapid population growth and restrictions caused by the inability to adequately finance government debt resulted in economic depression, unemployment and high food prices.[6] Combined with a regressive tax system and resistance to reform by the ruling elite, the result was a crisis Louis XVI proved unable to manage.[7][8]

From the late 17th century on, political and cultural debate became part of wider European society, rather than being confined to a small elite. This took different forms, such as the English 'coffeehouse culture', and extended to areas colonised by Europeans, particularly British North America. Contacts between diverse groups in Edinburgh, Geneva, Boston, Amsterdam, Paris, London or Vienna were much greater than often appreciated.[9] Cohesion between these groups was fostered by shared experiences; it was common to study at a foreign university or participate in the European cultural expedition known as the Grand Tour, while many were fluent in more than one language.[10]

Transnational elites who shared ideas and styles were not new; what changed was their extent and the numbers involved.[10] Under Louis XIV, the Court at Versailles was the centre of culture, fashion and political power. Improvements in education and literacy over the course of the 18th century meant larger audiences for newspapers and journals, with Masonic lodges, coffee houses and reading clubs providing areas where people could debate and discuss ideas. The emergence of this so-called "public sphere" led to Paris replacing Versailles as the cultural and intellectual centre, leaving the Court isolated and less able to influence opinion.[11]

In addition to these social changes, the French population grew from 18 million in 1700 to 26 million in 1789, making it the most populous state in Europe; Paris had over 600,000 inhabitants, of whom roughly one third were either unemployed or had no regular work.[12] Inefficient agricultural methods meant domestic farmers could not support these numbers, while primitive transportation networks made it hard to maintain supplies even when there was sufficient. As a result, food prices rose by 65% between 1770 and 1790, yet real wages increased by only 22%.[13] Food shortages were particularly damaging for the regime, since many blamed price increases on government failure to prevent profiteering.[14] By the spring of 1789, a poor harvest followed by a severe winter had created a rural peasantry with nothing to sell, and an urban proletariat whose purchasing power had collapsed.[15]

The other major drag on the economy was state debt. Traditional views of the French Revolution often attribute the financial crisis of the 1780s to heavy expenditure in the 1778–1783 Anglo-French War, but modern economic studies show this is incorrect. In 1788, the ratio of debt to gross national income in France was 55.6%, compared to 181.8% in Britain. Although French borrowing costs were higher, the percentage of tax revenue devoted to interest payments was about the same in both countries.[16]

However, these taxes were predominantly paid by the urban and rural poor, and attempts to share the burden more equally were blocked by the regional parlements which controlled financial policy.[17] The resulting impasse in the face of widespread economic distress led to the calling of the Estates-General, which became radicalised by the struggle for control of public finances.[18] However, neither the level of French state debt in 1788, or its previous history, can be considered an explanation for the outbreak of revolution in 1789.[19]

Although Louis was not indifferent to the crisis, when faced with opposition he tended to back down.[20] The court became the target of popular anger, especially Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was viewed as a spendthrift Austrian spy, and blamed for the dismissal of 'progressive' ministers like Jacques Necker. For their opponents, Enlightenment ideas on equality and democracy provided an intellectual framework for dealing with these issues, while the American Revolution was seen as confirmation of their practical application.[21]

Crisis of the Ancien Régime

Financial crisis

.png.webp)

In the century preceding the Revolution, the French state faced a series of budgetary crises. These primarily arose from structural deficiencies, rather than lack of resources; unlike Britain, where Parliament determined both expenditures and taxes, in France, the Crown controlled spending, but not revenue.[22] Only the Estates-General could approve a national tax, but this body had not been called since 1614, and its revenue collection functions had been taken over by the regional parlements. (see Map).[23]

Originally set up as law courts, by the mid-18th century the parlements had wide control over tax and legal affairs, the most powerful being the Parlement de Paris. Although willing to authorise one-time taxes, the parlements were reluctant to pass long-term measures. They outsourced tax collection to the Ferme générale, so the yield from the taxes they did approve was significantly reduced. So although larger and wealthier than Britain, France struggled to service its debt.[22]

Following a partial default in 1770, efforts were made to improve collection of revenues and reduce costs. By 1776, reforms instituted by Turgot, the Finance Minister, balanced the budget and reduced government borrowing costs from 12% per year to under 6%.[24] He opposed intervention in America, arguing that France could not afford it, and was dismissed in May 1776; his successor was the Swiss Protestant Jacques Necker, who was replaced in 1781 by Charles de Calonne.[25]

The war from 1778 to 1783 was financed by borrowing, and created a large French rentier class, which lived on interest they earned by holding government debt. By 1785, the government was struggling to cover these payments. Its options were to either default, or get the parlements to approve tax increases. When the parlements refused, Calonne persuaded Louis to summon the Assembly of Notables, an advisory council dominated by the upper nobility. Led by de Brienne, former archbishop of Toulouse, [lower-alpha 1] the Assembly argued that tax increases could only be authorised by the Estates-General.[27] In May 1787, Brienne replaced Calonne as Finance Minister; Necker was re-appointed in August 1788 and Louis summoned the Estates-General to assemble in May 1789.[28]

Estates-General of 1789

The Estates-General was split into three bodies: the clergy, or First Estate, nobility, or Second Estate, and the commons, or Third Estate.[29] Each of the three sat separately, enabling the First and Second Estates to outvote the Third,[30] despite representing less than 5% of the population. In the 1789 elections, the First Estate returned 303 deputies, representing 100,000 Catholic clergy; nearly 10% of French lands were controlled by bishops and monasteries, while the Church collected its own taxes from peasants.[31] Fifty-one were bishops; the wealthiest had incomes of 50,000 livres a year but more than two-thirds were priests who lived on less than 500 livres per year, and who were often closer to the urban and rural poor than the lawyers and officials of the Third Estate.[32]

The Second Estate elected 291 deputies, representing about 400,000 men and women, who owned about 25% of the land and collected seigneurial dues and rents from their peasant tenants. Like the clergy, this was not a uniform body, and was divided into the noblesse d'épée, or traditional aristocracy, and the noblesse de robe. The latter derived rank from judicial or administrative posts and tended to be hard-working professionals, who dominated the regional parlements and were often intensely socially conservative. Neither the First or Second Estates paid any taxes.[33]

610 deputies sat for the Third Estate, in theory representing 95% of the population, although voting rights were restricted to French-born or naturalised male taxpayers, aged 25 or more, residing where the vote was to take place. Half were well-educated lawyers or local officials, nearly a third in trades or industry, while fifty-one were wealthy land owners.[34]

To assist their delegates, each region completed a list of grievances, known as Cahiers de doléances.[35] Although they contained ideas that would have seemed radical only months before, most supported the monarchy, and assumed the Estates-General would agree to financial reforms, rather than fundamental constitutional change.[36] The lifting of press censorship allowed widespread distribution of political writings, mostly written by liberal members of the aristocracy and upper middle-class.[37] Abbé Sieyès, a political theorist and priest elected to the Third Estate, argued that since it represented 95% of the population, the Third Estate should take precedence over the other two.[38]

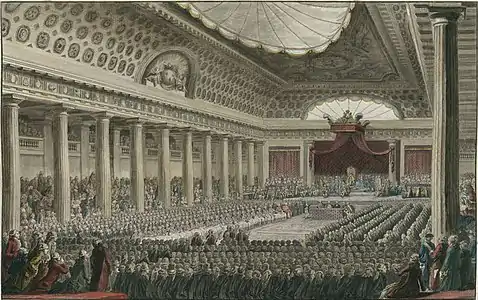

The Estates-General convened in the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi on 5 May 1789, near the Palace of Versailles rather than in Paris; the choice of location was interpreted as an attempt to control their debates. As was customary, each Estate assembled in separate rooms, whose furnishings and opening ceremonies deliberately emphasised the superiority of the First and Second Estates. They also insisted on enforcing the rule that only those who owned land could sit as deputies for the Second Estate, and thus excluded the immensely popular Comte de Mirabeau.[39]

Since the system ensured the clergy and nobility could always outvote the commons, a key objective was to ensure all three sat as one body. Led by Sieyès, the Third Estate demanded the credentials of all deputies be approved by the Estates-General as a whole, instead of each Estate verifying its own members; once they were approved, the built-in weighting of the Estates-General in favour of a minority would dissolve. After an extended stalemate, Necker suggested that each Estate verify its own members' credentials and the king act as arbitrator, but this was rejected.[40]

On 10 June, Sieyès moved that the Third Estate proceed to verify its own deputies, and invite the other two to do the same and not wait. This process was complete on 17 June. By 19 June, the Third Estate was joined by over 100 members of the clergy, and these deputies declared themselves the National Assembly. The remaining deputies from the other two Estates were invited to join, but the Assembly made it clear they intended to legislate with or without their support.[41]

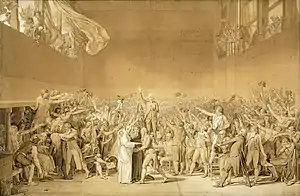

In an attempt to prevent the Assembly from convening, Louis XVI ordered the Salle des États closed down, claiming it needed to be prepared for a royal speech. On 20 June, the deputies met in a tennis court outside Versailles, where they took the Tennis Court Oath, undertaking not to disperse until they had given France a constitution.[42] By 27 June, they had been joined by the majority of the clergy, plus forty-seven members of the nobility, and Louis backed down. Messages of support for the Assembly poured in from Paris and other cities.[43]

Constitutional monarchy (July 1789 – September 1792)

Abolition of the Ancien Régime

Even these limited reforms went too far for reactionaries like Marie Antoinette and Louis' younger brother the Comte d'Artois; on their advice, Louis dismissed Necker as chief minister on 11 July.[44] On 12 July, the Assembly went into a non-stop session after rumours circulated he was planning to use the Swiss Guards to force it to close. The news brought crowds of protestors into the streets, and the elite Gardes Françaises regiment refused to disperse them.[45]

On the 14th, many of these regulars joined the mob in attacking the Bastille, a royal fortress with a large stores of arms and ammunition. After several hours of fighting that cost the lives of 83 attackers, its governor, Marquis de Launay, surrendered. He was taken to the Hôtel de Ville and executed, his head placed on a pike and paraded around the city; the fortress was then torn down in a remarkably short time. Although rumoured to hold many prisoners, the Bastille held only seven: four forgers, two noblemen held for "immoral behaviour", and a murder suspect. Nevertheless, as a potent symbol of the Ancien Régime, its destruction was viewed as a triumph and Bastille Day is still celebrated every year.[46]

Alarmed by the violence, Louis backed down and appointed the marquis de Lafayette commander of the National Guard. A new governmental structure was created for Paris known as the Commune, headed by Jean-Sylvain Bailly, former president of the Assembly. On 17 July, Louis visited Paris accompanied by 100 deputies. He was met by Bailly and accepted a tricolore cockade to loud cheers. However, it was clear power had shifted from his court; he was welcomed as 'Louis XVI, father of the French and king of a free people.'[47]

The short-lived unity enforced on the Assembly by a common threat quickly dissipated. Deputies argued over constitutional forms, while civil authority rapidly deteriorated. On 22 July, former Finance Minister Joseph Foullon and his son were lynched by a Parisian mob, and neither Bailly nor Lafayette could prevent it. In rural areas, wild rumours and paranoia resulted in the formation of militia and an agrarian insurrection known as la Grande Peur.[48] The breakdown of law and order and frequent attacks on aristocratic property led much of the nobility to flee abroad. These émigrés funded reactionary forces within France and urged foreign monarchs to back a counter-revolution.[49]

In response to this unrest, the Assembly published the August Decrees, ending feudalism and other privileges held by the nobility, notably exemption from tax. The decrees included equality before the law, opening public office to all, converting the church tithe into payments subject to redemption, freedom of worship, and cancellation of special privileges held by provinces and towns.[50]

Over 25% of French farmland had been subject to feudal dues, which provided most of the income of large landowners. The original intention was that their tenants would pay compensation, but the majority refused to do so and the obligation was cancelled in 1793, along with the tithe.[51]

The suspension of the 13 regional parlements in November 1789 meant that in the four months since August the main institutional pillars of the old regime had all been abolished. In their place, they substituted "the modern, autonomous individual, free to do whatever was not prohibited by law."

From its early stages, the Revolution displayed signs of its radical nature; what remained to be determined were the mechanisms for turning intentions into practical applications.[52]

Creating a new constitution

Assisted by Thomas Jefferson, Lafayette prepared a draft constitution known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which echoed some of the provisions of the Declaration of Independence. However France had reached no consensus on the role of the Crown, and until this question was settled, it was impossible to create political institutions. When presented to the legislative committee on 11 July, it was rejected by pragmatists such as Jean Joseph Mounier, President of the Assembly, who feared creating expectations that could not be satisfied.[53]

After editing by Mirabeau, it was published on 26 August as a statement of principle.[54] Considered one of the most important political documents in history, it contained provisions then considered radical in any European society, let alone France in 1789. Arguments between French and American historians over responsibility for its wording continue, but most agree the reality is a mix. Although Jefferson made major contributions to Lafayette's draft, he himself acknowledged an intellectual debt to Montesquieu, and the final version was significantly different.[55] French historian Georges Lefebvre argues that combined with the elimination of privilege and feudalism, it "highlighted equality in a way the (American Declaration of Independence) did not".[56]

More importantly, the two differed in intent; Jefferson saw the US Constitution and Bill of Rights as fixing the political system at a specific point in time, claiming they 'contained no original thought...but expressed the American mind' at that stage.[57] The 1791 French Constitution was viewed as a starting point, the Declaration providing an aspirational vision, a key difference between the two Revolutions. Attached as a preamble to the 1791 Constitution, and that of the Third Republic (1870-1940), it was incorporated into the current French Constitution in 1958.[58]

Discussions continued. Mounier, supported by conservatives like Gérard de Lally-Tollendal, wanted a bicameral system, with an upper house appointed by the king, who would have the right of veto. On 10 September, the majority led by Sieyès and Talleyrand rejected this in favour of a single assembly, while Louis retained only a "suspensive veto"; this meant he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it. On this basis, a new committee was convened to agree on a constitution; the most controversial issue was citizenship, linked to the debate on the balance between individual rights and obligations. Ultimately, the 1791 Constitution distinguished between 'active citizens' who held political rights, defined as French males over the age of 25, who paid direct taxes equal to three days' labour, and 'passive citizens', who were restricted to 'civil rights'. As a result, it was never fully accepted by radicals in the Jacobin club.[59]

Food shortages and the worsening economy caused frustration at the lack of progress, and the Parisian working-class, or sans culottes, became increasingly restive. This came to a head in late September, when the Flanders Regiment arrived in Versailles to take over as the royal bodyguard and in line with normal practice were welcomed with a ceremonial banquet. Popular anger was fuelled by press descriptions of this as a 'gluttonous orgy', and claims the tricolor cockade had been abused. The arrival of these troops was also viewed as an attempt to intimidate the Assembly.[60]

On 5 October 1789, crowds of women assembled outside the Hôtel de Ville, urging action to reduce prices and improve bread supplies.[61] These protests quickly turned political, and after seizing weapons stored at the Hôtel de Ville, some 7,000 marched on Versailles, where they entered the Assembly to present their demands. They were followed by 15,000 members of the National Guard under Lafayette, who tried to dissuade them, but took command when it became clear they would desert if he did not grant their request.[62]

When the National Guard arrived later that evening, Lafayette persuaded Louis the safety of his family required relocation to Paris. Next morning, some of the protestors broke into the Royal apartments, searching for Marie Antoinette, who escaped. They ransacked the palace, killing several guards. Although the situation remained tense, order was eventually restored, and the Royal family and Assembly left for Paris, escorted by the National Guard.[63] Announcing his acceptance of the August Decrees and the Declaration, Louis committed to constitutional monarchy, and his official title changed from 'King of France' to 'King of the French'.[64]

Revolution and the church

Historian John McManners argues "in eighteenth-century France, throne and altar were commonly spoken of as in close alliance; their simultaneous collapse ... would one day provide the final proof of their interdependence." One suggestion is that after a century of persecution, some French Protestants actively supported an anti-Catholic regime, a resentment fuelled by Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire.[65] Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote it was "manifestly contrary to the law of nature... that a handful of people should gorge themselves with superfluities while the hungry multitude goes in want of necessities."[66]

The Revolution caused a massive shift of power from the Catholic Church to the state; although the extent of religious belief has been questioned, elimination of tolerance for religious minorities meant by 1789 being French also meant being Catholic.[67] The church was the largest individual landowner in France, controlling nearly 10% of all estates and levied tithes, effectively a 10% tax on income, collected from peasant farmers in the form of crops. In return, it provided a minimal level of social support.[68]

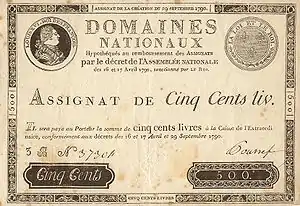

The August decrees abolished tithes, and on 2 November the Assembly confiscated all church property, the value of which was used to back a new paper currency known as assignats. In return, the state assumed responsibilities such as paying the clergy and caring for the poor, the sick and the orphaned.[69] On 13 February 1790, religious orders and monasteries were dissolved, while monks and nuns were encouraged to return to private life.[70] The Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 12 July 1790 made them employees of the state, as well as establishing rates of pay and a system for electing priests and bishops. Pope Pius VI and many French Catholics objected to this since it denied the authority of the Pope over the French Church. In October, thirty bishops wrote a declaration denouncing the law, further fuelling opposition.[71]

When clergy were required to swear loyalty to the Civil Constitution in November 1790, fewer than 24% did so; the result was a schism with those who refused, the 'non-juring' or 'Refractory clergy'.[72] This stiffened popular resistance against state interference, especially in traditionally Catholic areas such as Normandy, Brittany and the Vendée, where only a few priests took the oath and the civilian population turned against the revolution.[71] Widespread refusal led to further legislation against the clergy, many of whom were forced into exile, deported, or executed.[73]

Political divisions

The period from October 1789 to spring 1791 is usually seen as one of relative tranquility, when some of the most important legislative reforms were enacted. While certainly true, many provincial areas experienced conflict over the source of legitimate authority, where officers of the Ancien Régime had been swept away, but new structures were not yet in place. This was less obvious in Paris, since the formation of the National Guard made it the best policed city in Europe, but growing disorder in the provinces inevitably affected members of the Assembly.[74]

Centrists led by Sieyès, Lafayette, Mirabeau and Bailly created a majority by forging consensus with monarchiens like Mounier, and independents including Adrien Duport, Barnave and Alexandre Lameth. At one end of the political spectrum, reactionaries like Cazalès and Maury denounced the Revolution in all its forms, with extremists like Maximilien Robespierre at the other. He and Jean-Paul Marat gained increasing support for opposing the criteria for 'active citizens', which had disenfranchised much of the Parisian proletariat. In January 1790, the National Guard tried to arrest Marat for denouncing Lafayette and Bailly as 'enemies of the people'.[75]

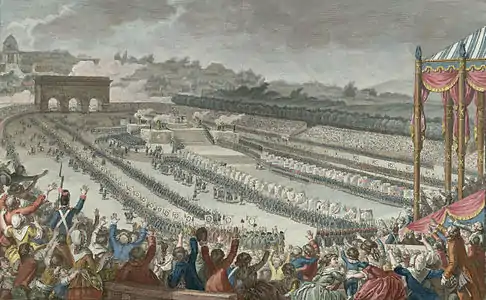

On 14 July 1790, celebrations were held throughout France commemorating the fall of the Bastille, with participants swearing an oath of fidelity to 'the nation, the law and the king.' The Fête de la Fédération in Paris was attended by Louis XVI and his family, with Talleyrand performing a mass. Despite this show of unity, the Assembly was increasingly divided, while external players like the Paris Commune and National Guard competed for power. One of the most significant was the Jacobin club; originally a forum for general debate, by August 1790 it had over 150 members, split into different factions.[76]

The Assembly continued to develop new institutions; in September 1790, the regional Parlements were abolished and their legal functions replaced by a new independent judiciary, with jury trials for criminal cases. However, moderate deputies were uneasy at popular demands for universal suffrage, labour unions and cheap bread, and over the winter of 1790 and 1791, they passed a series of measures intended to disarm popular radicalism. These included exclusion of poorer citizens from the National Guard, limits on use of petitions and posters, and the June 1791 Le Chapelier Law suppressing trade guilds and any form of worker organisation.[77]

The traditional force for preserving law and order was the army, which was increasingly divided between officers, who largely came from the nobility, and ordinary soldiers. In August 1790, the loyalist General Bouillé suppressed a serious mutiny at Nancy; although congratulated by the Assembly, he was criticised by Jacobin radicals for the severity of his actions. Growing disorder meant many professional officers either left or became émigrés, further destabilising the institution.[78]

Varennes and after

Held in the Tuileries Palace under virtual house arrest, Louis XVI was urged by his brother and wife to re-assert his independence by taking refuge with Bouillé, who was based at Montmédy with 10,000 soldiers considered loyal to the Crown.[79] The royal family left the palace in disguise on the night of 20 June 1791; late the next day, Louis was recognised as he passed through Varennes, arrested and taken back to Paris. The attempted escape had a profound impact on public opinion; since it was clear Louis had been seeking refuge in Austria, the Assembly now demanded oaths of loyalty to the regime, and began preparing for war, while fear of 'spies and traitors' became pervasive.[80]

Despite calls to replace the monarchy with a republic, Louis retained his position but was generally regarded with acute suspicion and forced to swear allegiance to the constitution. A new decree stated retracting this oath, making war upon the nation, or permitting anyone to do so in his name would be considered abdication. However, radicals led by Jacques Pierre Brissot prepared a petition demanding his deposition, and on 17 July, an immense crowd gathered in the Champ de Mars to sign. Led by Lafayette, the National Guard was ordered to "preserve public order" and responded to a barrage of stones by firing into the crowd, killing between 13 and 50 people.[81]

The massacre badly damaged Lafayette's reputation; the authorities responded by closing radical clubs and newspapers, while their leaders went into exile or hiding, including Marat. [82] On 27 August, Emperor Leopold II and Frederick William II of Prussia issued the Declaration of Pillnitz declaring their support for Louis, and hinting at an invasion of France on his behalf. In reality, Leopold and Frederick had met to discuss the Partitions of Poland, and the Declaration was primarily made to satisfy Comte d'Artois and other émigrés. Nevertheless, the threat rallied popular support behind the regime.[83]

Based on a motion proposed by Robespierre, existing deputies were barred from elections held in early September for the French Legislative Assembly. Although Robespierre himself was one of those excluded, his support in the clubs gave him a political power base not available to Lafayette and Bailly, who resigned respectively as head of the National Guard and the Paris Commune. The new laws were gathered together in the 1791 Constitution, and submitted to Louis XVI, who pledged to defend it "from enemies at home and abroad". On 30 September, the Constituent Assembly was dissolved, and the Legislative Assembly convened the next day.[84]

Fall of the monarchy

The Legislative Assembly has often been dismissed as an ineffective body, fatally compromised by divisions over the role of the monarchy and the 1791 Constitution. These were exacerbated by Louis' refusal to accept limitations on his powers and attempts to mobilise external support to reverse it, combined with discontent over rising prices due to monetary inflation, which particularly impacted the urban working class.[85] Restricting the franchise to those who paid a minimum amount of tax meant only 4 out of 6 million Frenchmen over 25 were able to vote; many of those excluded were the sans culottes, who increasingly saw the new regime as failing to meet their demands for bread and work.[86]

As a result, the new constitution was opposed by significant elements inside and outside the Assembly, which was broadly split into three main groups. 245 were affiliated with the Feuillants, led by Barnave, constitutional monarchists who considered the Revolution had gone far enough. 136 were Jacobin leftists, led by Brissot and often referred to as Brissotins, who regarded Louis with hostility and wanted a republic. The remaining 345 belonged to La Plaine, a central faction who switched votes depending on the issue; many of these were also deeply suspicious of the king.[87]

Despite being a minority, the Brissotins controlled key committees, which allowed them to focus on two issues, intended to portray Louis as hostile to the Revolution by making him use his veto. The first concerned émigrés; between October and November, the Assembly approved measures confiscating their property and threatening them with the death penalty.[88] The second was non-juring priests; opposition to the Civil Constitution had resulted in a state of near civil war in southern France, which Bernave tried to defuse by relaxing the more punitive provisions. On 29 November, the Assembly passed a decree giving refractory clergy eight days to comply, or face charges of 'conspiracy against the nation', which even Robespierre viewed as too far, too soon. As expected, Louis vetoed both.[89]

Accompanying this was a campaign for war against Austria and Prussia, also led by Brissot, whose aims have been interpreted as a mixture of cynical calculation and revolutionary idealism. It exploited popular anti-Austrianism, especially as represented by Marie Antoinette, but also a genuine belief in exporting the values of political liberty and popular sovereignty.[90] Ironically, Marie Antoinette headed a faction within the court that also favoured war, seeing it as a way to win control of the military, and restore royal authority. In December 1791, Louis made a speech to the Assembly giving foreign powers a month to disperse the émigrés or face war; it was greeted with enthusiasm by his supporters, but suspicion by his opponents.[91]

Bernave's failure to respond adequately to Austrian demands resulted in Louis appointing a new government, chiefly composed of Brissotins. On 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria and Prussia, beginning the French Revolutionary Wars, but suffered a series of disastrous defeats. In an attempt to gain support, the government ordered non-juring priests to swear the oath or be deported, dissolved the Constitutional Guard and replaced it with 20,000 fédérés; Louis agreed to disband the Guard, but vetoed the other two proposals, while Lafayette called on the Assembly to suppress the clubs.[92]

Popular anger increased when details of the Brunswick Manifesto reached Paris on 1 August; issued by the Prussian commander, it threatened the capital with 'unforgettable vengeance' should any oppose steps to restore the power of the monarchy. On the morning of 10 August, a combined force of Parisian National Guard and provincial fédérés attacked the Tuileries Palace, killing many of the Swiss Guard protecting it.[93] Louis and his family took refuge with the Assembly and shortly after 11:00 am, the deputies present voted to 'temporarily relieve the king', effectively suspending the monarchy.[94]

First Republic (1792–1795)

Proclamation of the First Republic

In late August, elections were held for the National Convention; further restrictions meant votes cast fell to 3.3 million, versus 4 million in 1791, while intimidation was widespread.[95] The former Brissotins now split into moderate Girondins led by Brissot, and radical Montagnards, headed by Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton and Jean-Paul Marat. While loyalties constantly shifted, around 160 of the 749 deputies were Girondists, 200 Montagnards and 389 members of La Plaine. Led by Bertrand Barère, Pierre Joseph Cambon and Lazare Carnot, as before this central faction acted as a swing vote.[96]

From 2 to 6 September, a series of extrajudicial killings took place in Paris, known as the September Massacres. Between 1,100 and 1,600 prisoners held in Parisian jails were summarily executed; more than 72% were common criminals.[97] A response to the capture of Longwy and Verdun by Prussia, the perpetrators were largely National Guard members and fédérés on their way to the front. Exactly who was responsible for their organisation is disputed, but even moderates expressed sympathy for the killings, which soon spread to the provinces.[98]

On 20 September, the French army won a stunning victory over the Prussians at Valmy. Emboldened by this, on 22 September the Convention abolished the monarchy and established the French First Republic. It also introduced a new calendar, and 1792 became Year One of the new republic.[99] The next few months were taken up with the trial of Citoyen Louis Capet, formerly Louis XVI. Members of the convention were evenly divided on the question of his guilt, but increasingly influenced by radicals concentrated in the Jacobin clubs and Paris Commune. The Brunswick Manifesto made it easy to portray Louis as a threat to the Revolution, confirmed when extracts from his personal correspondence allegedly showed him conspiring with Royalist exiles serving in their armies.[100]

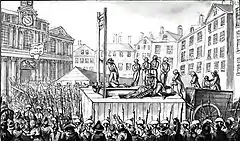

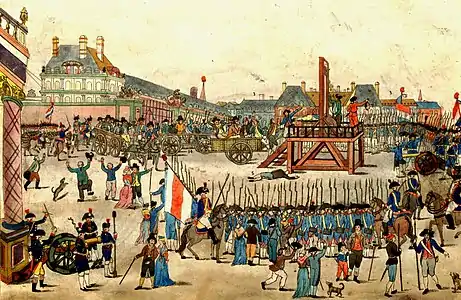

On 17 January 1793, the Assembly condemned Louis to death for "conspiracy against public liberty and general safety", by a margin of 361 to 288; another 72 members voted to execute him subject to a variety of delaying conditions. The sentence was carried out on 21 January on the Place de la Révolution, now the Place de la Concorde.[101] Horrified conservatives across Europe called for the destruction of revolutionary France; in February the Convention anticipated this by declaring war on Britain and the Dutch Republic; these countries were later joined by Spain, Portugal, Naples and the Tuscany in the War of the First Coalition.[102]

Political crisis and fall of the Girondins

.jpg.webp)

The Girondins hoped war would unite the people behind the government and provide an excuse for rising prices and food shortages, but found themselves the target of popular anger. Many left for the provinces. The first conscription measure (levée en masse) on 24 February sparked riots in Paris and other regional centres. Already unsettled by changes imposed on the church, in March the traditionally conservative and royalist Vendée rose in revolt. On 18th, Dumouriez was defeated at Neerwinden and defected to the Austrians. Uprisings followed in Bordeaux, Lyon, Toulon, Marseilles and Caen. The Republic seemed on the verge of collapse.[103]

The crisis led to the creation on 6 April 1793 of the Committee of Public Safety, an executive committee accountable to the convention.[104] The Girondins made a fatal political error by indicting Marat before the Revolutionary Tribunal for allegedly directing the September massacres; he was quickly acquitted, further isolating the Girondins from the sans-culottes. When Jacques Hébert called for a popular revolt against the "henchmen of Louis Capet" on 24 May, he was arrested by the Commission of Twelve, a Girondin-dominated tribunal set up to expose 'plots'. In response to protests by the Commune, the Commission warned "if by your incessant rebellions something befalls the representatives of the nation,...Paris will be obliterated".[103]

Growing discontent allowed the clubs to mobilise against the Girondins. Backed by the Commune and elements of the National Guard, on 31 May they attempted to seize power in a coup. Although the coup failed, on 2 June the convention was surrounded by a crowd of up to 80,000, demanding cheap bread, unemployment pay and political reforms, including restriction of the vote to the sans-culottes, and the right to remove deputies at will.[105] Ten members of the commission and another twenty-nine members of the Girondin faction were arrested, and on 10 June, the Montagnards took over the Committee of Public Safety.[106]

Meanwhile, a committee led by Robespierre's close ally Saint-Just was tasked with preparing a new Constitution. Completed in only eight days, it was ratified by the convention on 24 June, and contained radical reforms, including universal male suffrage and abolition of slavery in French colonies. However, normal legal processes were suspended following the assassination of Marat on 13 July by the Girondist Charlotte Corday, which the Committee of Public Safety used as an excuse to take control. The 1793 Constitution itself was suspended indefinitely in October.[107]

Key areas of focus for the new government included creating a new state ideology, economic regulation and winning the war.[108] The urgent task of suppressing internal dissent was helped by divisions among their opponents; while areas like the Vendée and Brittany wanted to restore the monarchy, most supported the Republic but opposed the regime in Paris. On 17 August, the Convention voted a second levée en masse; despite initial problems in equipping and supplying such large numbers, by mid-October Republican forces had re-taken Lyon, Marseilles and Bordeaux, while defeating Coalition armies at Hondschoote and Wattignies.[109]

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror began as a way to harness revolutionary fervour, but quickly degenerated into the settlement of personal grievances. At the end of July, the Convention set price controls over a wide range of goods, with the death penalty for hoarders, and on 9 September 'revolutionary groups' were established to enforce them. On 17th, the Law of Suspects ordered the arrest of suspected "enemies of freedom", initiating what became known as the "Terror". According to archival records, from September 1793 to July 1794 some 16,600 people were executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activity; another 40,000 may have been summarily executed or died awaiting trial.[110]

Fixed prices, death for 'hoarders' or 'profiteers', and confiscation of grain stocks by groups of armed workers meant that by early September Paris was suffering acute food shortages. However, France's biggest challenge was servicing the huge public debt inherited from the former regime, which continued to expand due to the war. Initially financed by sales of confiscated property, this was hugely inefficient; since few would buy assets that might be repossessed, fiscal stability could only be achieved by continuing the war until French counter-revolutionaries had been defeated. As internal and external threats to the Republic increased, the position worsened; dealing with this by printing assignats led to inflation and higher prices.[111]

On 10 October, the Convention recognised the Committee of Public Safety as the supreme Revolutionary Government, and suspended the Constitution until peace was achieved.[107] In mid-October, Marie Antoinette was found guilty of a long list of crimes and guillotined; two weeks later, the Girondist leaders arrested in June were also executed, along with Philippe Égalité. Terror was not confined to Paris; over 2,000 were killed after the recapture of Lyons.[112]

%252C_orateur_et_homme_politique_-_P712_-_mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp)

At Cholet on 17 October, the Republican army won a decisive victory over the Vendée rebels, and the survivors escaped into Brittany. Another defeat at Le Mans on 23 December ended the rebellion as a major threat, although the insurgency continued until 1796. The extent of the brutal repression that followed has been debated by French historians since the mid-19th century.[113] Between November 1793 to February 1794, over 4,000 were drowned in the Loire at Nantes under the supervision of Jean-Baptiste Carrier. Historian Reynald Secher claims that as many as 117,000 died between 1793 and 1796. Although those numbers have been challenged, François Furet concluded it "not only revealed massacre and destruction on an unprecedented scale, but a zeal so violent that it has bestowed as its legacy much of the region's identity."[114] [lower-alpha 2]

At the height of the Terror, the slightest hint of counter-revolutionary thought could place one under suspicion, and even its supporters were not immune. Under the pressure of events, splits appeared within the Montagnard faction, with violent disagreements between radical Hébertists and moderates led by Danton.[lower-alpha 3] Robespierre saw their dispute as de-stabilising the regime, and as a deist he objected to the anti-religious policies advocated by the atheist Hébert. He was arrested and executed on 24 March with 19 of his colleagues, including Carrier.[118] To retain the loyalty of the remaining Hébertists, Danton was arrested and executed on 5 April with Camille Desmoulins, after a show trial that arguably did more damage to Robespierre than any other act in this period.[119]

The Law of 22 Prairial (10 June) denied "enemies of the people" the right to defend themselves. Those arrested in the provinces were now sent to Paris for judgement; from March to July, executions in Paris increased from five to twenty-six a day.[120] Many Jacobins ridiculed the festival of the Cult of the Supreme Being on 8 June, a lavish and expensive ceremony led by Robespierre, who was also accused of circulating claims he was a second Messiah. Relaxation of price controls and rampant inflation caused increasing unrest among the sans-culottes, but the improved military situation reduced fears the Republic was in danger. Many feared their own survival depended on Robespierre's removal; during a meeting on 29 June, three members of the Committee of Public Safety called him a dictator in his face.[121]

Robespierre responded by not attending sessions, allowing his opponents to build a coalition against him. In a speech made to the convention on 26 July, he claimed certain members were conspiring against the Republic, an almost certain death sentence if confirmed. When he refused to give names, the session broke up in confusion. That evening he made the same speech at the Jacobins club, where it was greeted with huge applause and demands for execution of the 'traitors'. It was clear if his opponents did not act, he would; in the Convention next day, Robespierre and his allies were shouted down. His voice failed when he tried to speak, a deputy crying "The blood of Danton chokes him!"[122]

The Convention authorised his arrest; he and his supporters took refuge in the Hotel de Ville, defended by the National Guard. That evening, units loyal to the Convention stormed the building, and Robespierre was arrested after a failed suicide attempt. He was executed on 28 July with 19 colleagues, including Saint-Just and Georges Couthon, followed by 83 members of the Commune.[123] The Law of 22 Prairial was repealed, any surviving Girondists reinstated as deputies, and the Jacobin Club was closed and banned.[124]

There are various interpretations of the Terror and the violence with which it was conducted; Marxist historian Albert Soboul saw it as essential to defend the Revolution from external and internal threats. François Furet argues the intense ideological commitment of the revolutionaries and their utopian goals required the extermination of any opposition.[125] A middle position suggests violence was not inevitable but the product of a series of complex internal events, exacerbated by war.[126]

Thermidorean reaction

The bloodshed did not end with the death of Robespierre; Southern France saw a wave of revenge killings, directed against alleged Jacobins, Republican officials and Protestants. Although the victors of Thermidor asserted control over the Commune by executing their leaders, some of the leading "terrorists" retained their positions. They included Paul Barras, later chief executive of the French Directory, and Joseph Fouché, director of the killings in Lyon who served as Minister of Police under the Directory, the Consulate and Empire. Others were exiled or prosecuted, a process that took several months.[127]

The December 1794 Treaty of La Jaunaye ended the Chouannerie in western France by allowing freedom of worship and the return of non-juring priests.[128] This was accompanied by military success; in January 1795, French forces helped the Dutch Patriots set up the Batavian Republic, securing their northern border.[129] The war with Prussia was concluded in favour of France by the Peace of Basel in April 1795, while Spain made peace shortly thereafter.[130]

However, the Republic still faced a crisis at home. Food shortages arising from a poor 1794 harvest were exacerbated in Northern France by the need to supply the army in Flanders, while the winter was the worst since 1709.[131] By April 1795, people were starving and the assignat was worth only 8% of its face value; in desperation, the Parisian poor rose again.[132] They were quickly dispersed and the main impact was another round of arrests, while Jacobin prisoners in Lyon were summarily executed.[133]

A committee drafted a new constitution, approved by plebiscite on 23 September 1795 and put into place on 27th.[134] Largely designed by Pierre Daunou and Boissy d'Anglas, it established a bicameral legislature, intended to slow down the legislative process, ending the wild swings of policy under the previous unicameral systems. The Council of 500 was responsible for drafting legislation, which was reviewed and approved by the Council of Ancients, an upper house containing 250 men over the age of 40. Executive power was in the hands of five Directors, selected by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the lower house, with a five-year mandate.[135]

Deputies were chosen by indirect election, a total franchise of around 5 million voting in primaries for 30,000 electors, or 0.5% of the population. Since they were also subject to stringent property qualification, it guaranteed the return of conservative or moderate deputies. In addition, rather than dissolving the previous legislature as in 1791 and 1792, the so-called 'law of two-thirds' ruled only 150 new deputies would be elected each year. The remaining 600 Conventionnels kept their seats, a move intended to ensure stability.[136]

Directory (1795–1799)

The Directory has a poor reputation amongst historians; for Jacobin sympathisers, it represented the betrayal of the Revolution, while Bonapartists emphasised its corruption to portray Napoleon in a better light.[137] Although these criticisms were certainly valid, it also faced internal unrest, a stagnating economy and an expensive war, while hampered by the impracticality of the constitution. Since the Council of 500 controlled legislation and finance, they could paralyse government at will, and as the Directors had no power to call new elections, the only way to break a deadlock was to rule by decree or use force. As a result, the Directory was characterised by "chronic violence, ambivalent forms of justice, and repeated recourse to heavy-handed repression."[138]

Retention of the Conventionnels ensured the Thermidorians held a majority in the legislature and three of the five Directors, but they faced an increasing challenge from the right. On 5 October, Convention troops led by Napoleon put down a royalist rising in Paris; when the first elections were held two weeks later, over 100 of the 150 new deputies were royalists of some sort.[139] The power of the Parisian san culottes had been broken by the suppression of the May 1795 revolt; relieved of pressure from below, the Jacobins became natural supporters of the Directory against those seeking to restore the monarchy.[140]

Removal of price controls and a collapse in the value of the assignat led to inflation and soaring food prices. By April 1796, over 500,000 Parisians were reportedly in need of relief, resulting in the May insurrection known as the Conspiracy of the Equals. Led by the revolutionary François-Noël Babeuf, their demands included the implementation of the 1793 Constitution and a more equitable distribution of wealth. Despite limited support from sections of the military, it was easily crushed, with Babeuf and other leaders executed.[141] Nevertheless, by 1799 the economy had been stabilised and important reforms made allowing steady expansion of French industry; many remained in place for much of the 19th century.[142]

Prior to 1797, three of the five Directors were firmly Republican; Barras, Révellière-Lépeaux and Jean-François Rewbell, as were around 40% of the legislature. The same percentage were broadly centrist or unaffiliated, along with two Directors, Étienne-François Letourneur and Lazare Carnot. Although only 20% were committed Royalists, many centrists supported the restoration of the exiled Louis XVIII in the belief this would end the War of the First Coalition with Britain and Austria.[143] The elections of May 1797 resulted in significant gains for the right, with Royalists Jean-Charles Pichegru elected President of the Council of 500, and Barthélemy appointed a Director.[144]

With the royalists apparently on the verge of power, the Republicans staged a coup on 4 September. Using troops from Bonaparte's Army of Italy under Pierre Augereau, the Council of 500 was forced to approve the arrest of Barthélemy, Pichegru and Carnot. The election results were cancelled, sixty-three leading royalists deported to French Guiana and new laws passed against émigrés, Royalists and ultra-Jacobins. Although the power of the monarchists had been destroyed, it opened the way for direct conflict between Barras and his opponents on the left.[145]

Despite general war weariness, fighting continued and the 1798 elections saw a resurgence in Jacobin strength. The invasion of Egypt in July 1798 confirmed European fears of French expansionism, and the War of the Second Coalition began in November. Without a majority in the legislature, the Directors relied on the army to enforcing decrees and extract revenue from conquered territories. This made generals like Bonaparte and Joubert essential political players, while both the army and the Directory became notorious for their corruption.[146]

It has been suggested the Directory did not collapse for economic or military reasons, but because by 1799, many 'preferred the uncertainties of authoritarian rule to the continuing ambiguities of parliamentary politics'.[147] The architect of its end was Sieyès, who when asked what he had done during the Terror answered "I survived". Nominated to the Directory, he now turned his attention to removing Barras, using a coalition that included Talleyrand and former Jacobin Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother and president of the Council of 500.[148] On 9 November 1799, the Coup of 18 Brumaire replaced the five Directors with the French Consulate, Bonaparte, Sieyès, and Roger Ducos; most historians consider this the end point of the French Revolution.[149]

French Revolutionary Wars

The Revolution initiated a series of conflicts that began in 1792 and ended only with Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo in 1815. In its early stages, this seemed unlikely; the 1791 Constitution specifically disavowed "war for the purpose of conquest", and although traditional tensions between France and Austria re-emerged in the 1780s, Emperor Joseph cautiously welcomed the reforms. Austria was at war with the Ottomans, as were the Russians, while both were negotiating with Prussia over partitioning Poland. Most importantly, Britain preferred peace, and as Emperor Leopold stated after the Declaration of Pillnitz, "without England, there is no case".[150]

In late 1791, factions within the Assembly came to see war as a way to unite the country and secure the Revolution by eliminating hostile forces on its borders and establishing its "natural frontiers".[151] France declared war on Austria in April 1792 and issued the first levée en masse (conscription) orders. Since it expected a short war, the recruits were to serve for twelve months. By the time peace finally came in 1815, the conflict had involved every major European power as well as the United States, redrawn the map of Europe and expanded into the Americas, the Middle East and Indian Ocean.[152]

From 1701 to 1801, the population of Europe grew from 118 to 187 million; combined with new mass production techniques, this allowed belligerents to support large armies, requiring the mobilisation of national resources. It was a different kind of war, fought by nations rather than kings, intended to destroy their opponents' ability to resist, but also to implement deep-ranging social change. While all wars are political to some degree, this period was remarkable for the emphasis placed on reshaping boundaries and the creation of entirely new European states.[153]

In April 1792, French armies invaded the Austrian Netherlands but suffered a series of setbacks before victory over an Austrian-Prussian army at Valmy in September. After defeating a second Austrian army at Jemappes on 6 November, they occupied the Netherlands, areas of the Rhineland, Nice and Savoy. Emboldened by this success, in February 1793 France declared war on the Dutch Republic, Spain and Britain, beginning the War of the First Coalition.[154] However, the expiration of the 12-month term for the 1792 recruits forced the French to relinquish their conquests. In August, new conscription measures were passed and by May 1794 the French army had between 750,000 and 800,000 men.[155] Despite high rates of desertion, this was large enough to manage multiple internal and external threats; for comparison, the combined Prussian-Austrian army was less than 90,000.[156]

By February 1795, France had annexed the Austrian Netherlands, established their frontier on the left bank of the Rhine and replaced the Dutch Republic with the Batavian Republic, a satellite state. These victories led to the collapse of the anti-French coalition; Prussia made peace in April 1795, followed soon after by Spain, leaving Britain and Austria as the only major powers still in the war.[157] In October 1797, a series of defeats by Bonaparte in Italy led Austria to agree to the Treaty of Campo Formio, in which they formally ceded the Netherlands and recognised the Cisalpine Republic.[158]

Fighting continued for two reasons; first, French state finances had come to rely on indemnities levied on their defeated opponents. Second, armies were primarily loyal to their generals, for whom the wealth achieved by victory and the status it conferred became objectives in themselves. Leading soldiers like Hoche, Pichegru and Carnot wielded significant political influence and often set policy; Campo Formio was approved by Bonaparte, not the Directory, which strongly objected to terms it considered too lenient.[158]

Despite these concerns, the Directory never developed a realistic peace programme, fearing the destabilising effects of peace and the consequent demobilisation of hundreds of thousands of young men. As long as the generals and their armies stayed away from Paris, they were happy to allow them to continue fighting, a key factor behind sanctioning Bonaparte's invasion of Egypt. This resulted in aggressive and opportunistic policies, leading to the War of the Second Coalition in November 1798.[159]

French colonial policy

Although the French Revolution had a dramatic impact in numerous areas of Europe,[160] the French colonies felt a particular influence. As the Martinican author Aimé Césaire put it, "there was in each French colony a specific revolution, that occurred on the occasion of the French Revolution, in tune with it."[161]

The Haitian Revolution (Saint Domingue) became a central example of slave uprisings in French colonies. In the 1780s, Saint-Domingue had been France's wealthiest colony, producing more sugar than all of the British West Indies colonies put together. During the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794, months after rebelling slaves had already announced an abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue.[162] However, the 1794 decree was only implemented in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and Guyane, and was a dead letter in Senegal, Mauritius, Réunion and Martinique, the last of which had been conquered by the British, who maintained the institution of slavery on that Caribbean island.[163]

Media and symbolism

Newspapers

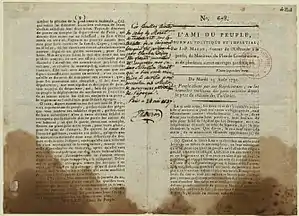

Newspapers and pamphlets played a central role in stimulating and defining the Revolution. Prior to 1789, there have been a small number of heavily censored newspapers that needed a royal licence to operate, but the Estates-General created an enormous demand for news, and over 130 newspapers appeared by the end of the year. Among the most significant were Marat's L'Ami du peuple and Elysée Loustallot's Revolutions de Paris.[164] Over the next decade, more than 2,000 newspapers were founded, 500 in Paris alone. Most lasted only a matter of weeks but they became the main communication medium, combined with the very large pamphlet literature.[165]

Newspapers were read aloud in taverns and clubs, and circulated hand to hand. There was a widespread assumption writing was a vocation not a business, and the role of the press advancement of civic republicanism.[166] By 1793 the radicals were most active but initially the royalists flooded the country with their publication the "L'Ami du Roi" (Friends of the King) until they were suppressed.[167]

Revolutionary symbols

To illustrate the differences between the new Republic and the old regime, the leaders needed to implement a new set of symbols to be celebrated instead of the old religious and monarchical symbols. To this end, symbols were borrowed from historic cultures and redefined, while those of the old regime were either destroyed or reattributed acceptable characteristics. These revised symbols were used to instil in the public a new sense of tradition and reverence for the Enlightenment and the Republic.[168]

La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" (French pronunciation: [la maʁsɛjɛːz]) became the national anthem of France. The song was written and composed in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin". The French National Convention adopted it as the First Republic's anthem in 1795. It acquired its nickname after being sung in Paris by volunteers from Marseille marching on the capital.

The song is the first example of the "European march" anthemic style, while the evocative melody and lyrics led to its widespread use as a song of revolution and incorporation into many pieces of classical and popular music. De Lisle was instructed to 'produce a hymn which conveys to the soul of the people the enthusiasm which it (the music) suggests.'[169]

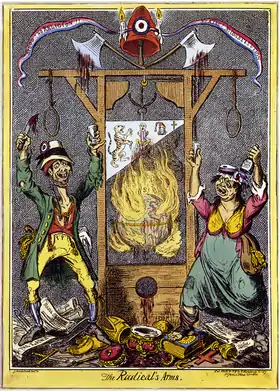

Guillotine

The guillotine remains "the principal symbol of the Terror in the French Revolution."[170] Invented by a physician during the Revolution as a quicker, more efficient and more distinctive form of execution, the guillotine became a part of popular culture and historic memory. It was celebrated on the left as the people's avenger and cursed as the symbol of the Terror by the right.[171]

Its operation became a popular entertainment that attracted great crowds of spectators. Vendors sold programmes listing the names of those scheduled to die. Many people came day after day and vied for the best locations from which to observe the proceedings; knitting women (tricoteuses) formed a cadre of hardcore regulars, inciting the crowd. Parents often brought their children. By the end of the Terror, the crowds had thinned drastically. Repetition had staled even this most grisly of entertainments, and audiences grew bored.[172]

Cockade, tricolore and liberty cap

Cockades were widely worn by revolutionaries beginning in 1789. They now pinned the blue-and-red cockade of Paris onto the white cockade of the Ancien Régime. Camille Desmoulins asked his followers to wear green cockades on 12 July 1789. The Paris militia, formed on 13 July, adopted a blue and red cockade. Blue and red are the traditional colours of Paris, and they are used on the city's coat of arms. Cockades with various colour schemes were used during the storming of the Bastille on 14 July.[173]

The Liberty cap, also known as the Phrygian cap, or pileus, is a brimless, felt cap that is conical in shape with the tip pulled forward. It reflects Roman republicanism and liberty, alluding to the Roman ritual of manumission, in which a freed slave receives the bonnet as a symbol of his newfound liberty.[174]

Role of women

The role of women in the Revolution has long been a topic of debate. Deprived of political rights under the Ancien Regime, the 1791 Constitution classed them as "passive" citizens, leading to demands for social and political equality for women and an end to male domination. They expressed these demands using pamphlets and clubs such as the Cercle Social, whose largely male members viewed themselves as contemporary feminists.[175] However, in October 1793, the Assembly banned all women's clubs and the movement was crushed; this was driven by the emphasis on masculinity in a wartime situation, antagonism towards feminine "interference" in state affairs due to Marie Antoinette, and traditional male supremacy.[176] A decade later the Napoleonic Code confirmed and perpetuated women's second-class status.[177]

At the beginning of the Revolution, women took advantage of events to force their way into the political sphere, swore oaths of loyalty, "solemn declarations of patriotic allegiance, [and] affirmations of the political responsibilities of citizenship." Activists included Girondists like Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, and Charlotte Corday, the killer of Marat. Others like Théroigne de Méricourt, Pauline Léon and the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women supported the Jacobins, staged demonstrations in the National Assembly and took part in the October 1789 March to Versailles. Despite this, the constitutions of 1791 and 1793 denied them political rights and democratic citizenship.[178]

On 20 June 1792 a number of armed women took part in a procession that "passed through the halls of the Legislative Assembly, into the Tuileries Garden, and then through the King's residence."[179] Women also assumed a special role in the funeral of Marat, following his murder on 13 July 1793 by Corday; as part of the funeral procession, they carried the bathtub in which he died, as well as a shirt stained with his blood.[180] On 20 May 1793 women were in the forefront of a crowd demanding "bread and the Constitution of 1793"; when they went unnoticed, they began "sacking shops, seizing grain and kidnapping officials."[181]

The Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, a militant group on the far left, demanded a law in 1793 that would compel all women to wear the tricolour cockade to demonstrate their loyalty to the Republic. They also demanded vigorous price controls to keep bread – the major food of the poor people – from becoming too expensive. After the Convention passed the law in September 1793, the Revolutionary Republican Women demanded vigorous enforcement, but were countered by market women, former servants, and religious women who adamantly opposed price controls (which would drive them out of business ) and resented attacks on the aristocracy and on religion. Fist fights broke out in the streets between the two factions of women.

Meanwhile, the men who controlled the Jacobins rejected the Revolutionary Republican Women as dangerous rabble-rousers. At this point the Jacobins controlled the government; they dissolved the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, and decreed that all women's clubs and associations were illegal. They sternly reminded women to stay home and tend to their families by leaving public affairs to the men. Organised women were permanently shut out of the French Revolution after 30 October 1793.[182]

Prominent women

Olympe de Gouges wrote a number of plays, short stories, and novels. Her publications emphasised that women and men are different, but this shouldn't prevent equality under the law. In her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen she insisted that women deserved rights, especially in areas concerning them directly, such as divorce and recognition of illegitimate children.[183]

Madame Roland (a.k.a. Manon or Marie Roland) was another important female activist. Her political focus was not specifically on women or their liberation. She focused on other aspects of the government, but was a feminist by virtue of the fact that she was a woman working to influence the world. Her personal letters to leaders of the Revolution influenced policy; in addition, she often hosted political gatherings of the Brissotins, a political group which allowed women to join. As she was led to the scaffold, Madame Roland shouted "O liberty! What crimes are committed in thy name!"[184]

Most of these activists were punished for their actions. Many of the women of the Revolution were even publicly executed for "conspiring against the unity and the indivisibility of the Republic".[185]

Counter-revolutionary women

A major aspect of the French Revolution was the dechristianisation movement, a movement strongly rejected by many devout people. Especially for women living in rural areas of France, the closing of the churches meant a loss of normalcy.[186]

When these revolutionary changes to the Church were implemented, it sparked a counter-revolutionary movement among women. Although some of these women embraced the political and social amendments of the Revolution, they opposed the dissolution of the Catholic Church and the formation of revolutionary cults like the Cult of the Supreme Being.[187] As Olwen Hufton argues, these women began to see themselves as the "defenders of faith".[188] They took it upon themselves to protect the Church from what they saw as a heretical change to their faith, enforced by revolutionaries.

Counter-revolutionary women resisted what they saw as the intrusion of the state into their lives.[189] Economically, many peasant women refused to sell their goods for assignats because this form of currency was unstable and was backed by the sale of confiscated Church property. By far the most important issue to counter-revolutionary women was the passage and the enforcement of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790. In response to this measure, women in many areas began circulating anti-oath pamphlets and refused to attend masses held by priests who had sworn oaths of loyalty to the Republic. These women continued to adhere to traditional practices such as Christian burials and naming their children after saints in spite of revolutionary decrees to the contrary.[190]

Economic policies

.png.webp)

The French Revolution abolished many of the constraints on the economy that had slowed growth in the Ancien régime. It abolished tithes owed to local churches and feudal dues owed to landlords. The results hurt tenants, who paid both higher rents and higher taxes.[191] It nationalised all church lands, as well as lands of royalists who went into exile. It planned to use these seized lands to finance the government by issuing assignats. It abolished the guild system as a worthless remnant of feudalism.[192] It also abolished the highly inefficient system of tax farming, whereby private individuals would collect taxes for a hefty fee. The government seized the foundations that had been set up (starting in the 13th century) to provide an annual stream of revenue for hospitals, poor relief, and education. The state sold the lands but typically local authorities did not replace the funding and so most of the nation's charitable and school systems were massively disrupted.[193]

The economy did poorly in 1790–96 as industrial and agricultural output dropped, foreign trade plunged, and prices soared. The government decided not to repudiate old debts. Instead it issued more and more paper money (assignats) supposedly backed by seized lands. The result was escalating inflation. The government imposed price controls and persecuted speculators and traders in the black market. People increasingly refused to pay taxes and the annual government deficit increased from 10% of gross national product in 1789 to 64% in 1793. By 1795, after the bad harvest of 1794 and the removal of price controls, inflation reached a level of 3500%. The assignats were withdrawn in 1796 but their replacements also fuelled inflation. Inflation was finally ended by Napoleon in 1803 with the franc as the new currency.[194]

Napoleon after 1799 paid for his expensive wars by multiple means, starting with the modernisation of the rickety financial system.[195] He conscripted soldiers at low wages, raised taxes, placed large-scale loans, sold lands formerly owned by the Catholic Church, sold Louisiana to the United States, plundered conquered areas and seized food supplies, and levied requisitions on countries he controlled, such as Italy.[196]

Long-term impact

The French Revolution had a major impact on Europe and the New World, decisively changing the course of human history.[197] It ended feudalism and created the path for future advances in broadly defined individual freedoms.[198] [199] [5] Its impact on French nationalism was profound, while also stimulating nationalist movements throughout Europe.[200] Its influence was great in the hundreds of small German states and elsewhere, where it was either inspired by the French example or in reaction against it.[201]

France

The changes in France were enormous; some were widely accepted and others bitterly contested into the late 20th century.[202] Before the Revolution, the people had little power or voice. The kings had so thoroughly centralised the system that most nobles spent their time at Versailles, and thus played only a small direct role in their home districts. Thompson says that the kings had "ruled by virtue of their personal wealth, their patronage of the nobility, their disposal of ecclesiastical offices, their provincial governors (intendants) their control over the judges and magistrates, and their command of the Army."[203]

After the first year of revolution, the power of the king had been stripped away, he was left a mere figurehead, the nobility had lost all their titles and most of their land, the Church lost its monasteries and farmlands, bishops, judges and magistrates were elected by the people, and the army was almost helpless, with military power in the hands of the new revolutionary National Guard. The central elements of 1789 were the slogan "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity" and "The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen", which Lefebvre calls "the incarnation of the Revolution as a whole."[204]

The long-term impact on France was profound, shaping politics, society, religion and ideas, and polarising politics for more than a century. Historian François Aulard writes:

"From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life.... The French Revolution differed from other revolutions in being not merely national, for it aimed at benefiting all humanity."[205]

Religion and charity

The most heated controversy was over the status of the Catholic Church.[206] From a dominant position in 1788, it was almost destroyed in less than a decade, its priests and nuns turned out, its leaders dead or in exile, its property controlled by its enemies, and a strong effort underway to remove all influence of Christian religiosity, such as Sundays, holy days, saints, prayers, rituals and ceremonies. The movement to de-Christianise France not only failed but aroused a furious reaction among the pious.[207][208]

During the Terror, extreme efforts of dechristianisation took place, including the imprisonment and massacre of priests and destruction of churches and religious images throughout France. An effort was made to replace the Catholic Church altogether, with civic festivals replacing religious ones. The establishment of the Cult of Reason was the final step of radical de-Christianisation. These events led to widespread disillusionment with the Revolution and to counter-rebellions across France. Locals often resisted de-Christianisation by attacking revolutionary agents and hiding fugitive members of the clergy.

Robespierre, himself a deist, and the Committee of Public Safety were forced to denounce the campaign,[209] replacing the Cult of Reason with the deist but still non-Christian Cult of the Supreme Being. The Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon and the Church ended the de-Christianisation period and established the rules for a relationship between the Catholic Church and the French State that lasted until it was abrogated by the Third Republic via the separation of church and state on 11 December 1905. The persecution of the Church led to a counter-revolution known as the revolt in the Vendée.[210]

The Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon and the Church ended the de-Christianisation period and established the rules for a relationship between the Catholic Church and the French state that lasted until it was abrogated by the Third Republic via the separation of church and state on 11 December 1905. Napoleon's Concordat was a compromise that restored some of the Catholic Church's traditional roles but not its power, its lands or its monasteries. Priests and bishops were given salaries as part of a department of government controlled by Paris, not Rome. Protestants and Jews gained equal rights.[211] Battles over the role of religion in the public sphere, and closely related issues such as church-controlled schools, that were opened by the Revolution have never seen closure. They raged into the 20th century. By the 21st century, angry debates exploded over the presence of any Muslim religious symbols in schools, such as headscarves, for which Muslim girls could be expelled. J. Christopher Soper and Joel S. Fetzer explicitly link the conflict over religious symbols in public to the French Revolution, when the target was Catholic rituals and symbols.[212]

The revolutionary government seized charitable foundations that had been set up (starting in the 13th century) to provide an annual stream of revenue for hospitals, poor relief, and education. The state sold the lands but typically local authorities did not replace the funding and so most of the nation's charitable and school systems were massively disrupted.[193]