History of South Africa (1815–1910)

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Cape Colony was annexed by the British and officially became their colony in 1815. Britain encouraged settlers to the Cape, and in particular, sponsored the 1820 Settlers to farm in the disputed area between the colony and the Xhosa in what is now the Eastern Cape. The changing image of the Cape from Dutch to British excluded the Dutch farmers in the area, the Boers who in the 1820s started their Great Trek to the northern areas of modern South Africa. This period also marked the rise in power of the Zulu under their king Shaka Zulu. Subsequently, several conflicts arose between the British, Boers and Zulus, which led to the Zulu defeat and the ultimate Boer defeat in the Second Anglo-Boer War. However, the Treaty of Vereeniging established the framework of South African limited independence as the Union of South Africa.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of South Africa |

Arms of South Africa |

| Timeline |

|

|

British colonization

At the tip of the continent, the British found an established colony with 25,000 slaves, 20,000 white colonists, 15,000 Khoisan, and 1,000 freed black slaves. Power resided solely with a white élite in Cape Town, and differentiation on the basis of race was deeply entrenched. Outside Cape Town and the immediate hinterland, isolated black and white pastoralists populated the country.

Like the Dutch before them, the British initially had little interest in the Cape Colony, other than as a strategically located port. As one of their first tasks they tried to resolve a troublesome border dispute between the Boers and the Xhosa on the colony's eastern frontier. In 1820 the British authorities persuaded about 5,000 middle-class British immigrants (most of them "in trade") to leave England behind and settle on tracts of land between the feuding groups with the idea of providing a buffer zone. The plan was singularly unsuccessful. Within three years, almost half of these 1820 Settlers had retreated to the towns, notably Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth, to pursue the jobs they had held in Britain.

While doing nothing to resolve the border dispute, this influx of settlers solidified the British presence in the area, thus fracturing the relative unity of white South Africa. Where the Boers and their ideas had before gone largely unchallenged, European Southern Africa now had two language groups and two cultures. A pattern soon emerged whereby English-speakers became highly urbanised, and dominated politics, trade, finance, mining, and manufacturing, while the largely uneducated Boers were relegated to their farms.

The gap between the British settlers and the Boers further widened with the abolition of slavery in 1833, not because the slaves were freed, but the way in which they were freed (compensation for freed slaves, for example, had to be fetched personally in London). Yet the British settlers' conservatism and sense of racial superiority stopped any radical social reforms, and in 1841 the authorities passed a Masters and Servants Ordinance, which perpetuated white control. Meanwhile, British numbers increased rapidly in Cape Town, in the area east of the Cape Colony (present-day Eastern Cape Province), in Natal and, after the discovery of gold and diamonds, in parts of the Transvaal, mainly around present-day Gauteng.

Difaqane and destruction

The early 19th century saw a time of immense upheaval relating to the military expansion of the Zulu kingdom. Sotho-speakers know this period as the difaqane ("forced migration"); while Zulu-speakers call it the mfecane ("crushing").

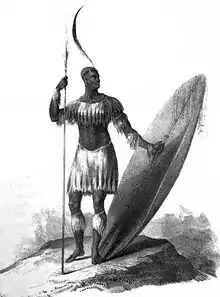

The full causes of the difaqane remain in dispute, although certain factors stand out. The rise of a unified Zulu kingdom had particular significance. In the early 19th century, Nguni tribes in KwaZulu-Natal began to shift from a loosely organised collection of kingdoms into a centralised, militaristic state. Shaka Zulu, son of the chief of the small Zulu clan, became the driving force behind this shift. At first something of an outcast, Shaka proved himself in battle and gradually succeeded in consolidating power in his own hands. He built large armies, breaking from clan tradition by placing the armies under the control of his own officers rather than of the hereditary chiefs. Shaka then set out on a massive programme of expansion, killing or enslaving those who resisted in the territories he conquered. His impis (warrior regiments) were rigorously disciplined: failure in battle meant death.

Peoples in the path of Shaka's armies moved out of his way, becoming in their turn aggressors against their neighbours. This wave of displacement spread throughout Southern Africa and beyond. It also accelerated the formation of several states, notably those of the Sotho (present-day Lesotho) and of the Swazi (now Swaziland).

In 1828 Shaka was killed by his half-brothers Dingaan and Umthlangana. The weaker and less-skilled Dingaan became king, relaxing military discipline while continuing the despotism. Dingaan also attempted to establish relations with the British traders on the Natal coast, but events had started to unfold that would see the demise of Zulu independence.

The Great Trek

Meanwhile, the Boers had started to grow increasingly dissatisfied with British rule in the Cape Colony. Various factors contributed to the migration, including Anglicization policies and restrictive laws on slavery. Beginning in 1835, several groups of Boers, together with large numbers of Khoikhoi and black servants, decided to trek off into the interior in search of greater independence. North and east of the Orange River (which formed the Cape Colony's frontier) these Boers or Voortrekkers ("Pioneers") found vast tracts of apparently uninhabited grazing lands. They had, it seemed, entered their promised land, with space enough for their cattle to graze and their culture of anti-urban independence to flourish. Little did they know that what they found – deserted pasture lands, disorganised bands of refugees, and tales of brutality – resulted from the difaqane, rather than representing the normal state of affairs.

With the exception of the more powerful Ndebele, the Voortrekkers encountered little resistance among the scattered peoples of the plains. The difaqane had dispersed them, and the remnants lacked horses and firearms. Their weakened condition also solidified the Boers' belief that European occupation meant the coming of civilization to a savage land. However, the mountains where King Moshoeshoe I had started to forge the Basotho nation that would later become Lesotho and the wooded valleys of Zululand proved a more difficult proposition. Here the Boers met strong resistance, and their incursions set off a series of skirmishes, squabbles, and flimsy treaties that would litter the next 50 years of increasing white domination.

British vs. Boers vs. Zulus

The Great Trek first halted at Thaba Nchu, near present-day Bloemfontein, where the trekkers established a republic. Following disagreements among their leadership, the various Voortrekker groups split apart. While some headed north, most crossed the Drakensberg into Natal with the idea of establishing a republic there. Since the Zulus controlled this territory, the Voortrekker leader Piet Retief paid a visit to King Dingaan, where the suspicious Zulu promptly killed him. This killing triggered other attacks by Zulus on the Boer population, and a revenge attack by the Boers. The culmination came on 16 December 1838, in the Battle of Blood River, fought at the Ncome River in Natal. Though several Boers suffered injuries, they managed to overcome the Zulus without suffering a single death. They killed several thousand Zulus, reportedly causing the Ncome's waters to run red.

After this victory, which resulted from the possession of superior weapons, the Boers felt that their expansion really did have a long suspected stamp of divine approval. Yet their hopes for establishing a Natal republic remained short lived. The British annexed the area in 1843, and founded their new Natal colony at present-day Durban. Most of the Boers, feeling increasingly squeezed between the British on one side and the native African populations on the other, headed north.

The British set about establishing large sugar plantations in Natal, but found few inhabitants of the neighbouring Zulu areas willing to provide labour. The British confronted stiff resistance to their encroachments from the Zulus, a nation with well-established traditions of waging war, who inflicted one of the most humiliating defeats on the British army at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879, where over 1400 British soldiers were killed. During the ongoing Anglo-Zulu Wars, the British eventually established their control over what was then named Zululand, and is today known as KwaZulu-Natal.

The British turned to India to resolve their labour shortage, as Zulu men refused to adopt the servile position of labourers and in 1860 the SS Truro arrived in Durban harbour with over 300 people on board. Over the next 50 years, 150,000 more indentured Indians arrived, as well as numerous free "passenger Indians", building the base for what would become the largest Indian community outside of India. As early as 1893, when Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Durban, Indians outnumbered whites in Natal. (See Asians in South Africa.)

Growth of independent South Africa

The Boer republics

The Boers meanwhile persevered with their search for land and freedom, ultimately establishing themselves in various Boer Republics, e.g. the Transvaal or South African Republic and the Orange Free State. For a while it seemed that these republics would develop into stable states, despite having thinly spread populations of fiercely independent Boers, no industry, and minimal agriculture. The discovery of diamonds near Kimberley turned the Boers' world on its head (1869). The first diamonds came from land belonging to the Griqua, but to which both the Transvaal and Orange Free State laid claim. Britain quickly stepped in and annexed the area for itself.

The discovery of the Kimberley diamond-mines unleashed a flood of European and black labourers into the area. Towns sprang up in which the inhabitants ignored the "proper" separation of whites and blacks, and the Boers expressed anger that their impoverished republics had missed out on the economic benefits of the mines.

The Anglo-Boer Wars

First Anglo-Boer War

Long-standing Boer resentment turned into full-blown rebellion in the Transvaal (under British control from 1877), and the first Anglo-Boer War, known to Afrikaners as the "War of Independence", broke out in 1880. The conflict ended almost as soon as it began with a crushing Boer victory at Battle of Majuba Hill (27 February 1881). The republic regained its independence as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek ("South African Republic"), or ZAR. Paul Kruger, one of the leaders of the uprising, became President of the ZAR in 1883. Meanwhile, the British, who viewed their defeat at Majuba as an aberration, forged ahead with their desire to federate the Southern African colonies and republics. They saw this as the best way to come to terms with the fact of a white Afrikaner majority, as well as to promote their larger strategic interests in the area.

Inter-war period

In 1879, Zululand came under British control. Then in 1886, an Australian prospector discovered gold in the Witwatersrand, accelerating the federation process and dealing the Boers yet another blow. Johannesburg's population exploded to about 100,000 by the mid-1890s, and the ZAR suddenly found itself hosting thousands of uitlanders, both black and white, with the Boers squeezed to the sidelines. The influx of English labour in particular worried the Boers, many of whom resented the English miners.

The enormous wealth of the mines, soon became irresistible for British imperialists. In 1895, a group of renegades led by Captain Leander Starr Jameson entered the ZAR with the intention of sparking an uprising on the Witwatersrand and installing a British administration. This incursion became known as the Jameson Raid. The scheme ended in fiasco, but it seemed obvious to Kruger that it had at least the tacit approval of the Cape Colony government, and that his republic faced danger. He reacted by forming an alliance with Orange Free State.

Second Anglo-Boer War

The situation peaked in 1899, when the British demanded voting rights for the 60,000 foreign whites on the Witwatersrand. Until that point, Kruger's government had excluded all foreigners from the franchise. Kruger rejected the British demand and called for the withdrawal of British troops from the ZAR's borders. When the British refused, Kruger declared war. This Second Anglo-Boer War lasted longer, and the British preparedness surpassed that of Majuba Hill. By June 1900, Pretoria, the last of the major Boer towns, had surrendered. Yet resistance by Boer bittereinders continued for two more years with guerrilla-style battles, which the British met in turn with scorched earth tactics. By 1902, 26,000 Boers (mainly women and children) had died of disease, hunger and neglect in concentration camps. On 31 May 1902 a superficial peace came with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging. Under its terms, the Boer republics acknowledged British sovereignty, while the British in turn committed themselves to reconstruction of the areas under their control.

Roots of union

.jpg.webp)

During the immediate post-war years the British focussed their attention on rebuilding the country, in particular the mining industry. By 1907 the mines of the Witwatersrand produced almost one-third of the world's annual gold production. But the peace brought by the treaty remained fragile and challenged on all sides. The Afrikaners found themselves in the position of poor farmers in a country where big mining ventures and foreign capital rendered them irrelevant. Britain's unsuccessful attempts to anglicise them, and to impose English as the official language in schools and the workplace particularly incensed them. Partly as a backlash to this, the Boers came to see Afrikaans as the volkstaal ("people's language") and as a symbol of Afrikaner nationhood. Several nationalist organisations sprang up.

Blacks and Coloureds remained marginalised in society. After much negotiation with the Boers a form of "segregation" was introduced. The authorities imposed unpopular taxes, while the British caretaker administrator encouraged the immigration of thousands of Chinese that undercut wages. Resentment exploded in the Bambatha Rebellion of 1906, in which 4,000 Zulus lost their lives after rebelling due to onerous tax legislation.

The British meanwhile moved ahead with their plans for union. After several years of negotiations, the South Africa Act 1909 brought the colonies and republics – Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal, and Orange Free State – together as the Union of South Africa. Under the provisions of the act, the Union remained British territory, but with home-rule for Afrikaners. The British High Commission territories of Basutoland (now Lesotho), Bechuanaland (now Botswana), Swaziland, and Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe) continued under direct rule from Britain.

English and Dutch became the official languages. Afrikaans did not gain recognition as an official language until 1925. Despite a major campaign by Blacks and Coloureds, the voter franchise remained as in the pre-Union republics and colonies, and only whites could gain election to Parliament.

1910 Union of South Africa

In 1910 the Union of South Africa was created by the unification of four areas, by joining the two former independent Boer republics of the South African Republic (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) and the Orange Free State (Oranje Vrystaat)with the British dominated Cape Province and Natal. Most significantly, the new self-governing Union of South Africa gained international respect with British Dominion status putting it on par with three other important British dominions and allies: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.[1]

References

- "The South Africa Act, 1909". The American Journal of International Law. 1 January 1910 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Lagden, Godfrey (1905). . The Empire and the century. London: John Murray. pp. 539–556.