Hook Nose

Roman Nose (c. 1823 – September 17, 1868), also known as Hook Nose (Cheyenne: Vóhko'xénéhe,[1] also spelled Woqini and Woquini), was a Native American of the Northern Cheyenne. He is considered to be one of, if not the greatest and most influential warriors during the Plains Indian War of the 1860s. Born during the prosperous days of the fur trade in the 1820s, he was called Môséškanetsénoonáhe ("Bat") as a youth. He later took the warrior name Wokini, which the whites rendered as Roman Nose. Considered invincible in combat, this fierce warrior distinguished himself in battle to such a degree that the U.S. military mistook him for the Chief of the entire Cheyenne nation.

Biography

Hook Nose was born around 1830 and was a Northern Suhtai, a band within the Northern Cheyenne tribe. A common mistake is to confuse him with a supposed son of the Minniconjou Lakota Sioux Lone Horn and brother of Spotted Elk and Touch the Clouds called Roman Nose.

Following the Sand Creek Massacre in November 1864, Hook Nose became a principal figure among his people, leading retaliatory strikes against Euro-American settlements at the Battle of Julesburg along the Platte Road and Powder River regions of south-central Wyoming and in the Platte valley of Nebraska, western Kansas, and eastern Colorado. The Native American author and physician Charles A. Eastman allegedly wrote of Hook Nose that, "Perhaps no other warrior attacked more emigrants along the Oregon Trail between 1860–1868."[2] Contrary to popular myth, Hook Nose was never a chief, nor a leader of any of the six Cheyenne military societies. However, known to all plains Indians as a great warrior, and the acknowledged leader during combat, Hook Nose's reputation spread among the whites who credited him with initiating most hostilities between the Cheyenne and U.S military. A member of the Crooked Lance Warrior Society, Hook Nose continually refused seats among the Cheyenne Chiefs and headsmen, and never held a position of authority within his tribe.

Physically imposing in stature, there are several historical references to Hook Nose's flamboyant, intimidating personality and battle prowess. Isaac Coates, General Winfield S. Hancock's surgeon, observed a verbal confrontation between Hancock and Hook Nose outside Fort Larned in April 1867. Coates wrote in his journal; "of all the chiefs, he is one of the finest specimens, physically, of his race. He is quite six feet in height, finely formed with a large body and muscular limbs. His appearance, decidedly military, and on this occasion, particularly so, since he wore the uniform of a General in the Army. A seven-shooting Spencer carbine hung at the side of his saddle, four large Navy revolvers stuck in his belt, and a bow, already strung with arrows, were grasped in his left hand. Thus armed and mounted on a fine horse, he was a good representative of the God of War; and his manner showed plainly that he did not care whether we talked or fought..."[3]

Hook Nose opposed treaties with the United States Federal Government, while other leaders urged peace. Following the implementation of the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865, Hook Nose moved south, pledging to assist his friends, Bull Bear, Grey Beard, and the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, defend their ancestral hunting grounds along the Smoky Hill River and within the Republican Valley. He was killed by American soldiers during the Battle of Beecher Island on September 17, 1868, while attempting to charge the island in the Arikaree River, and annihilate General Forsyth's command.

He was mostly known as "Roman Nose" among the Americans. Some of his other aliases were Arched Nose, and Woo-kay-nay. Hook Nose was known by his peers as being dedicated and willing to protect his people. Hook Nose was known as a warrior with many skillful and bold tactics to fight against his enemies. Hook Nose was also known to be a very spiritual individual and practiced traditional Cheyenne medicine. Hook Nose and his peers believed it was this medicine that protected him and made him such a great warrior.[4]

He died during the Battle at Beecher Island in 1868.[5] "He had refused a chieftaincy when young, on the grounds that he spent the major portion of his time in battle rather than in council".[6] Although Hook Nose never accepted the role of chief, many of his peers respected him as a leader and protector of his people and their resources. "Roman Nose, was a leader of Indian warriors and a member of the crooked Lance Society of the Cheyenne Indian Tribe".[5] Hook Nose's intentions might have been to protect his people; however, non-Indians perceived him a malicious man. "Roman Nose, the fierce Dog Soldier Warrior, was considered a 'bad' Indian. He wanted the white man evicted from the plains. His lance meant to sweep the lands clean of whites fences, houses, cattle and the 'iron horse'".[7] Hook Nose's leadership, battle tactics, and spirituality are a few things that made him known to many. Although he died fairly young, Hook Nose left an impact on the west during his time.[5]

Battle tactics and leadership skills

Hook Nose's battle tactics and leadership skills were not only known by his tribe, but also by other people who encountered him. "His bravery came naturally and spotless; his influence was enormous as he was the acknowledged leader in war...though he was not a chief".[8] Witnesses of Hook Nose's warfare talked highly about his tactics and leadership abilities. "A common battle tactic of his was to ride up and down the line of army troops within rifle range, getting them to discharge their weapons and waste their ammunition."[9] Hook Nose used deadly and malicious tactics to protect himself, his people, and his culture. "Roman Nose was a prominent Southern Cheyenne warrior best remembered for his key role in the ongoing battle against white advancement in the west throughout the 1860s".[5] Hook Nose did not accept the idea that the west was expanding and being industrialized. Giving in to the enemy did not seem to be an option for him.[5]

Spiritual practices

Hook Nose was known to be very spiritual. "He spent endless hours in preparing his medicine, his mind and his spirit".[10] It is believed the reason he would show up late to most battles was due, in part, in that he spent a longer amount of time than usual in prayer for blessings and to prepare for warfare.[9] It is known that Hook Nose would spend days on quests to cleanse his spirit and gain strength through his medicine.[11] Not only was Hook Nose protected by his medicine he gained through ceremony, but he also felt that he was protected by his famous War-bonnet that was made and given to him by White Bull.[12] It was also believed that it was because of his war-bonnet and the medicine he practiced to be the reason why he was such a successful warrior.[13]

Death and believed causes

It was believed that through Hook Nose's spiritual practices and his war-bonnet, he and others surrounding him were protected.[14] In order for his war-bonnet to protect him, there were certain rules and rituals he had to obey.[15] Some of these rules included never shaking hands with anyone, and never eating food that had been prepared or served using metal.[15] Hook Nose had complete faith in his war-bonnet, and believed that it had always protected him in battle.[15] Hook Nose and his fellow warriors believed that, on the morning of the Battle of Beecher's Island, Hook Nose's medicine had been tampered with.[9] Hook Nose had felt that something was wrong and said, "Something was done that I was told must not be done, the bread I ate was taken out of the frying pan with something made of iron... If I go into this fight I shall certainly be killed".[16]

The war bonnet

Hook Nose possessed an elaborate warbonnet that he believed gave him special powers. The medicine man Ice, later known as White Bull, made the warbonnet, and assured Hook Nose he would be impervious to the white man's bullets as long as he followed certain conditions. Hook Nose could not shake hands in the way of the white man, nor could he eat food that had been touched with any iron implement. Ice told Hook Nose that should he violate either of these conditions, he would surely be killed in battle.[17]

Several days prior to the Battle of Beecher Island, Hook Nose visited the nearby Sioux camp, where he participated in a feast. During the feast, he ate some fry bread. However, the woman who cooked the bread had used an iron fork to remove it from the cooking pan, which violated one of the conditions of his medicine.

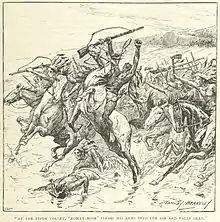

As he left for battle, he was made aware of this fact, but he did not have the time to perform the necessary cleansing ceremony to restore his medicine. Because of this, he did not participate in the fighting as he normally would, preferring to watch the battle from afar. During the battle, he was chastised by an elderly warrior named White Contrary for his lack of participation, and thus decided to enter the battle after all, knowing that he would die. After donning his war clothes, including his war bonnet, he led an assault on the island. He was shot at close range during the attack and died late that afternoon, near sunset.[18]

The demise of Hook Nose had devastating effects on the Cheyenne's efforts to defend their lands, which virtually ended with the defeat of Tall Bull and the Dog Soldiers, at the Battle of Summit Springs, near Sterling, Colorado, in July 1869.

References

- Cheyenne Dictionary, 2004–2007

- Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains, Mineola, Dover Publications, 1997, p. 86, ISBN 0-486-29608-3.

- Isaac Taylor Coates, On the Plains with Custer and Hancock: The Journal of Isaac Coates, Army Surgeon (edited by W. J. D. Kennedy), Boulder, Johnson Books, 1997, p. 64.

- Arlen, Shelly (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- Unknown (2003). "Roman Nose". Academic OneFile.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. Native American Literatures. 5 (1): 9–30. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. 5 (1): 9–30. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. 5 (1): 12. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Arlen, Shelley (1996). "Roman Nose". Encyclopedia of North American Indians.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo. 5 (1): 16. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. 5 (1): 16. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo. 5 (1): 19. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (Spring 1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. Native American Literatures. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Kenny, Maurice (1989). "Roman Nose, Cheyenne: A Brief Biography". Wicazo Sa Review. 5 (1): 23. doi:10.2307/1409218. JSTOR 1409218.

- Monnett, John H. (1992). The Battle of Beecher Island and the Indian War of 1867–1869. University Press of Colorado. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-87081-267-X.

- Monnett, John H. (1992). The Battle of Beecher Island and the Indian War of 1867–1869. University Press of Colorado. pp. 148–150. ISBN 0-87081-267-X.

Further reading

- "The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers", Chronicles of Oklahoma

- The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyenne, Stanley Hoig, University of Oklahoma Press, 1972.

- The Cheyenne Indians, George Bird Grinnell, University of Nebraska Press, 1972.

- The Battle of Beecher Island, The Beecher Island Battle Memorial Association, Wray, CO, 1996.

- "A White River Lakota Legend"

- "Butterfield Overland Dispatch" Marker, Ellis County, KS

- Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent – Caught Between the Worlds of the Indian and the White Man David F. Halaas and Andrew E. Masich, Da Capo Press, 2005.

- "Bold and Fearless" Painting, Nah si ha di ma

- Fort Wallace: Historical Marker, Wallace Co., KS

- Kidder Massacre: M Company, 2nd Cavalry

- Antonucci, Michael. Military History and Espionage. "Island of Death"