Horace Moore-Jones

Horace Millichamp Moore-Jones, first known as Horace Jones, (3 February 1868 – 3 April 1922) was a notable New Zealand artist, soldier and art teacher.

Horace Millichamp Moore-Jones | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Horace Moore-Jones | |

| Birth name | Horace Jones |

| Born | 3 February 1868 |

| Died | 3 April 1922 (aged 54) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | sapper |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Other work | War artist |

Born in Malvern Wells, Worcestershire, England, Moore-Jones and his family emigrated to New Zealand when he was about 17 years old. He soon became a professional artist and worked in both New Zealand and Australia. On the outbreak of the First World War, he volunteered for service in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). He participated in the Gallipoli Campaign initially as a sapper but later as a war artist. During his war service and for a time afterwards following his discharge from the NZEF in 1916 he produced a number of sketches and watercolour paintings of Gallipoli. After leaving the NZEF, he worked as an art teacher and conducted a number of exhibitions and lectures around New Zealand. He died in 1922 as a result of extensive burns while rescuing people from a fire which destroyed the Hamilton Hotel, in the city of Hamilton.

Early life

Born on 3 February 1868, Horace Jones was one of ten children of David Jones, an engineer by trade, and a school teacher, Sarah Ann née Garner. The family lived in Malvern Wells in the county of Worcestershire, England, at the time of his birth.[1] The Jones family emigrated to New Zealand around 1885, settling in Auckland, where Sarah Ann found work at a girls' school on Wellesley Street, in Remuera. Even as a child, Jones expressed an interest in art from an early age, and as a 22-year-old he received formal tuition from Anne Dobson, an art teacher in Auckland. Jones soon began a relationship with Dobson and the two married on 5 September 1891.[2]

Art career

Following their wedding, the couple moved to Australia to develop their respective careers as artists, settling in Sydney. It was at this time he changed his name to Horace Millichamp Moore-Jones. He soon developed a good reputation for portraiture and semi-allegorical works which were exhibited with the Art Society of New South Wales. Dobson, who had trained for a time at the Royal Academy in London, also enhanced her already well-known profile.[3] With his wife, Moore-Jones also operated an art school but finances were tight. When, Dobson became ill with tuberculosis, many of the couple's possessions were sold to keep make ends meet. In June 1901, Dobson died and this left Moore-Jones to raise a two-year-old daughter, Norma; two other children had died in their infancy.[4]

Moore-Jones remarried in 1905, to Florence née Mitchell, with whom he would have three more children. Despite living in Australia, he returned to New Zealand on several occasions. There were a number of exhibitions during this time, and he also executed his first example of war art, a painting of troop ships departing Auckland for South Africa during the Boer War. This work was presented to the Auckland Art Gallery in 1902.[5]

In 1908, Moore-Jones moved his family to Auckland and re-established himself as an artist there. To supplement his income he taught art at the girls' school in Remeura where his mother was headmistress. After four years, he went to London and enrolled in an art school there. He then became an artist on the staff of Pearson's Magazine.[1]

First World War

Moore-Jones, still in England, was 46 years old at the time of the outbreak of the First World War and decided to enlist in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). To do so, he falsified his date of birth and dyed his hair to appear more youthful. As he enlisted while in England, his initial military training was in Salisbury, where the British section of the NZEF was based. In December 1914, he joined up with the main body of the NZEF in Egypt.[1] To his disappointment, as he had hoped to serve in the infantry, Moore-Jones was posted to the New Zealand Engineers, with the rank of sapper (equivalent to private).[6]

On 25 April 1915, Moore-Jones was among the sapper contingent that landed late in the afternoon on Gallipoli. The sappers were immediately put to work building emplacements for howitzers and machine-guns, digging support trenches upon on the plateau where Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Plugge established his headquarters, and constructing tracks on Walker's Ridge. During this time, Moore-Jones made several sketches of his observations of the battlefield; some of these were later published in New Zealand newspapers.[7]

Coming to the attention of senior commanders due to his artistic skills, Moore-Jones was seconded to the ANZAC Printing Section, which was attached to Lieutenant-General William Birdwood's headquarters. Declining an offer of a commission, for he preferred to remain in the ranks, he made several topographical sketches of the terrain that was used for planning of offensive operations.[1] The dangers of his work were well understood, and Birdwood later commented: "Many of Moore-Jones' pictures were, I know, done while shells were whistling overhead, and they portray very faithfully the country in which we were operating..."[8] In October 1915, he was dispatched to Cairo to supervise the reproduction by the Survey Department of some of his sketches.[9]

In November 1915, a wound to Moore-Jones' hand prevented him from continuing with his sketching work and soon afterwards, he was medically evacuated to England. After recovering his health, he commenced work on a series of watercolours based on his Gallipoli sketches. These were exhibited in England in April 1916[1] and he also had an audience at Buckingham Palace with King George V.[10] His work was well received by the public and press. A selection of ten landscape images was published by the London publisher Hugh Rees in a portfolio that included commentary from General Sir Ian Hamilton, the overall commander at Gallipoli, as well as Major-General Alexander Godley, the commander of the NZEF, and Birdwood.[11]

Later in 1916, Moore-Jones was repatriated to New Zealand and discharged from the NZEF due to being medically unfit for active duty. He returned to his family in Auckland and continued creating paintings of the Gallipoli Campaign in between portraiture commissions. As a result of the publicity of his showings in England, there was considerable interest in his Gallipoli work and in November 1916, he gave the first of what proved to be several exhibitions, accompanied by a lecture, of his paintings.[12]

From late 1916 to 1917, his Gallipoli paintings were exhibited around New Zealand and it was during this time that he painted his most notable work, 'The Man with the Donkey'.[1] He went on tour with the paintings, giving talks about his experiences at Gallipoli. From February 1917, the proceeds from his lecturing went to the newly formed New Zealand Returned Soldiers' Association (RSA). His tour was well subscribed and proved to be of considerable financial benefit to the RSA.[13] Moore-Jones continued his fund efforts for the RSA into 1918, travelling to many smaller townships to display and lecture about his work at Gallipoli.[14]

Moore-Jones himself did not profit from the tour and short of finance, he, on more than one occasion in 1917, offered to sell his war paintings to the New Zealand Government. He believed that they should be exhibited in a national gallery to memorialise the New Zealand effort at Gallipoli. However, the economic situation of the time, together with Prime Minister William Massey's view that no one should profit from the war, meant that Moore-Jones' offers were declined. The following year the paintings were offered to the Auckland Art Gallery which declined to meet Moore-Jones' asking price of £1,500.[14] Eventually Moore-Jones sold his collection, which numbered 70 works, to the Australian Government for £1,500.[15]

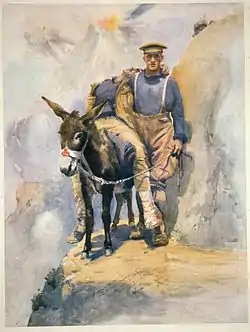

The Man with the Donkey

During a seminar in Dunedin in 1917 on his war experiences at Gallipoli, Moore-Jones mentioned his recollections of a man who, with the help of a donkey, transported wounded from the hills at Gallipoli to medical posts. An audience member loaned him a photograph, taken by James Jackson who served at Gallipoli with the New Zealand Medical Corps, of a medical orderly transporting a wounded soldier on a donkey. It was from this photograph,[16] now held by the Waikato Museum,[17] that Moore-Jones based his work entitled 'The Man with the Donkey'.[16]

Moore-Jones executed several versions of 'The Man with the Donkey', the first of which was completed in Dunedin the evening after he was given the photograph. Two others were painted when he returned to Auckland, and both of these were sent to England so that lithographs could be made.[18] At least of one of these included an inscription: "To the memory of our hero comrade 'Murphy' (Simpson) killed May 1915". This version is now at the Australian War Memorial,[19] while others hang at the Aigantighe Art Gallery in Timaru and the Christchurch Officers Club. Although at least six versions of the painting are known, all are dated '1915' by the artist rather than with the date of their execution.[18]

With only a couple of original versions in private hands, sales have been rare. The most recent was in 2015 when a version sold for almost $500,000.[20]

The medical orderly was originally believed, including by Moore-Jones, to be the Australian John Simpson Kirkpatrick, who served in the early stages of the Gallipoli Campaign before being killed by a sniper and who was well known for his use of donkeys to transport wounded soldiers from the front lines. However, by 1937 it became known that the man the subject of the photograph on which the painting was based on was not Simpson but Richard Alexander Henderson, a stretcher-bearer in the New Zealand Medical Corps.[18]

Later life

On a visit to Hamilton in 1918 to exhibit his work, Moore-Jones was offered a position as an art teacher at Hamilton High School. While his family remained in Auckland, he commuted to Hamilton for the working week, taking a room at the Hamilton Hotel, returning to his home for the weekends.[21] He continued to complete a number of paintings, including further copies of 'The Man with the Donkey'. Early in the morning of 3 April 1922, a fire broke out in the hotel kitchen. Moore-Jones helped to evacuate the guests to a fire escape. Believing a hotel maid to still be inside the burning building, he reentered to try and locate her. Unbeknown to him, the maid was not at the hotel that night. He made his way to another fire escape but received severe burns to his body. Taken to hospital, he died later that day.[22]

Survived by his wife and two children, Moore-Jones was buried at Purewa Cemetery in Auckland, along with another victim of the hotel fire. The funeral service was attended by prominent citizens of the city along with Lieutenant Reginald Judson, a Victoria Cross recipient of the war, who represented the New Zealand Military Forces.[23]

Legacy

Moore-Jones' artwork is exhibited at several major institutions in both New Zealand and Australia, including the Australian War Memorial, Auckland City Art Gallery, and the Waikato Museum.[1]

In December 2012, it was announced that Hamilton, where Moore-Jones had died, would rename a central city street from Marlborough Place to Sapper Moore-Jones Place in his honour.[24] On 27 March 2015, a bronze statue of Moore-Jones, was unveiled on Hamilton's Victoria Street facing the old site of the Hamilton Hotel. Sculpted by the official artist of the New Zealand Defence Force, Matt Gauldie, the statue stands 5 metres (16 ft 5 in) high and is mounted on a large block of stone donated by the Turkish Government and sourced from Gallipoli. It depicts the artist in a kneeling pose while performing a sketch on the Gallipoli battlefield.[25] Gauldie has also created small bronze statuettes based on Moore-Jones's most famous work, entitled Henderson and his Donkey.[26]

Notes

- Gray, Anne. "Horace Millichamp Moore-Jones". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 27–28.

- Haworth 2016, p. 28.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 28–29.

- Haworth 2016, p. 29.

- Haworth 2016, p. 33.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 36–37.

- Haworth 2016, p. 38.

- Haworth 2016, p. 40.

- "Aucklander at the Palace". Auckland Star (96). 22 April 1916. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 43–44.

- Haworth 2016, p. 52.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 52–53.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 64–65.

- Haworth 2016, p. 19.

- "Man with the Donkey: The Original Photo". Evening Post (66). 15 September 1937. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Neems, Jeff (7 December 2012). "Original Moore-Jones Image Gifted to City". Waikato Museum. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 62–63.

- Haworth 2016, p. 60.

- "Famous Gallipoli painting fetches almost half a million at auction". New Zealand Herald. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Haworth 2016, p. 64.

- Haworth 2016, pp. 66–67.

- "Hamilton Fire Victims: Funerals at Purewa". The New Zealand Herald (18059). 6 April 1922. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Leaman, Aaron (30 November 2012). "Governor to unveil Sapper Moore-Jones place". Waikato Times. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Leaman, Aaron (27 March 2015). "Bronze statue honours war artist". Waikato Times. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- "Henderson and his Donkey". Parnell Gallery. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

References

- Haworth, Jennifer (2016). Behind the Twisted Wire: New Zealand Artists in World War I. Christchurch, New Zealand: Wily Publications. ISBN 978-1-927167-21-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)