Horagalles

In Sami shamanism, Horagalles, also written Hora Galles and Thora Galles and often equated with Tiermes or Aijeke (i.e. "grandfather or great grandfather"), is the thunder god. He is depicted as a wooden figure with a nail in the head and with a hammer, or occasionally on shaman drums, two hammers. It has been suggested that name is derived from that of the Norse god Thor.

Characteristics and functions

Idols of Horagalles are made of wood and have a nail or spike and a piece of flint in the head.[1][2] He has a hammer called Wetschera, Aijeke Wetschera,[3][4] or Ajeke veċċera, "grandfather's hammer."[5]

Horagalles is the god of the sky, thunder and lightning, the rainbow, weather, oceans, and lakes and rules over human life, health and wellbeing.[6] He punishes "hurtful demons" or "evil spirits" (i.e., trolls) who frequent the rocks and mountains; he destroys them with his lightning, shoots them with his bow, or dashes their brains out with his hammer. The rainbow is his bow, "Aijeke dauge".[3][4][7]

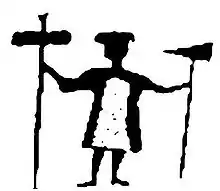

Horagalles depicted on Sami shaman drums

On Sami shaman drums Horagalles was occasionally depicted with a sledgehammer in one hand and a cross-hammer in the other, or symbolized by two crossed hammers. He made thunder and lightning with one hammer and withdrew them with the other to prevent damage.[6]

Name and relationship to other gods

The name Horagalles does not occur in older dictionaries of Sami languages, for instance in the mid-19th century.[10] He is often equated with Tiermes; in 1673 Johannes Scheffer, who did not use the name Horagalles, wrote that when Aijeke thundered, he was called Tiermes.[3][7] There is considerable regional variation in the names; Horagalles (with its various spellings, including Thoragalles) is characteristically southern Sami, and the rainbow is referred to by a variety of names referring to thunder.[1][5][11][12]

Early scholars noted the similarities between Horagalles and the Norse thunder-god Thor and that some Sami called him Thoron or simply Thor, and were unsure which had influenced which.[13] But the name Horagalles is now interpreted as a loanword from the Old Norse Þórr Karl, "the Old Man Thor,"[1][14] "Thor, the Elder,"[15] or "Thor fellow,"[16] "Thor Karl" (possibly from Norwegian Torrekall),[17][18] or Swedish Torsmannen, "the thunder man."[19]

Horagalles' consort is called Ravdna, and the red berries of the rowan tree are sacred to her. The name Ravdna resembles North Germanic names for the tree, such as Old Norse reynir, and according to the Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál, the rowan is called "the salvation of Thor" because Thor once saved himself by clinging to it. It has therefore been theorized that the Norse goddess Sif, Thor's wife, was once conceived of in the form of a rowan to which Thor clung.[14][16]

Tiermes

Tiermes is a Sami god of thunder and rain, also called Aijeke or Ajeke and often identified with Horagalles.

Tiermes is god of the sky and thunder and lightning, the rainbow, weather, oceans, and lakes and rules over human life, health, and well-being. He protects people and their animals from "hurtful demons" and "evil spirits" (i.e., trolls).[20] According to the mid-18th century Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, "Thiermes or Thoron" is the first in a trinity, of whom the other members are Storjunkare and Baivre or Jumala.[21] He is also called Aijeke, "grandfather" or "great-grandfather"; in 1673 Johannes Scheffer wrote that when Aijeke thundered, he was called Tiermes.[7]

The names of the god vary considerably between regions, with Tiermes and variants being commonly used among northern Sami and Horagalles and variants among southern Sami,[1][22] but unlike Horagalles, the name Tiermes is not a loanword; it is related to Torym, found in Siberia.[23][24]

References

- Kaarle Krohn, "Lappische Beiträge zur germanischen Mythologie," Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen 6 (1906) 155–80, p. 164 (in German)

- Johannes Scheffer, The History of Lapland: wherein are shewed the original manners, habits, marriages, conjurations, etc., of that people, Oxford, 1674, cited in Matthias Alexander Castrén, Nordiska Resor och Forskningar volume 3, Helsinki: Finska Litteratursällskapet, 1853, p. 206 (in Swedish)

- Scheffer, cited in Castrén, p. 50.

- Johannes Schefferus, Lappland, tr. Henrik Sundin, ed. John Granlund, Bengt Löw, and John Bernström, Acta Lapponica 8, Stockholm: Gebers, 1956, OCLC 468993787, p. 130 (in Swedish)

- Jens Andreas Friis, Lappisk Mythologi, Eventyr og Folkesagn, Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1871, p. 69 (in Norwegian)

- Friis, p. 68, citing Erich Johann Jessen, De norske Finners og Lappers hedenske Religion (1765).

- The History of Lapland, 1674 translated ed., facsimile ed. Suecica rediviva 22, Stockholm: Rediviva, 1971, ISBN 978-91-7120-001-3, p. 37.

- Friis, p. 35.

- Friis, p. 141.

- Nils Vibe Stockfleth, Norsk-lappisk Ordbog. Christiania: Cappelen, 1852.

- Friis, pp. 65–66.

- Håkan Rydving, The End of Drum-Time: Religious Change among the Lule Sami, 1670s–1740s, doctoral dissertation, Acta universitatis upsaliensis, Historia Religionum 12, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1993, ISBN 978-91-554-3065-8, p. 19.

- Friis, p. 66.

- E. O. G. Turville-Petre, (1964). Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964, OCLC 3264532, p. 98.

- Folklore 25–28 (2004) p. 49.

- Jaan Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1987, ISBN 978-0-8018-3413-4, p. 204.

- Georges Dumézil, Gods of the Ancient Northmen, ed. Einar Haugen, Publications of the UCLA Center for the Study of Comparative Folklore and Mythology 3, Berkeley: University of California, 1973, ISBN 978-0-520-02044-3, p. 124.

- Leopold von Schroeder, "Germanische Elben und Götter beim Estenvolke," Sitzungsberichte der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse 153.1 (1906) p. 92 (in German)

- Ørnulv Vorren and Ernst Manker, tr. Kathleen McFarlane, Lapp Life and Customs: A Survey, London: Oxford, 1962, OCLC 264994678, p. 119.

- Matthias Alexander Castrén, Nordiska Resor och Forskningar volume 3, Helsinki: Finska Litteratursällskapet, 1853, pp. 49–51 (in Swedish)

- Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, ed. Jean Frédéric Bernard and Jean-Charles Poncelin de La Roche-Tilhac, 2nd ed., volume 1 Amsterdam/Paris: Laporte, 1783, OCLC 13814643, p. 57 (in French)

- Jens Andreas Friis, Lappisk Mythologi, Eventyr og Folkesagn, Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1871, pp. 65–66, 69 (in Norwegian)

- Folklore 25–28 (2004) p. 49.

- Ørnulv Vorren and Ernst Manker, tr. Kathleen McFarlane, Lapp Life and Customs: A Survey, London: Oxford, 1962, OCLC 264994678, p. 119.

Further reading

- Axel Olrik. "Nordisk og lappisk gudsdyrkelse." Danske Studier 1905, pp. 39–63. (in Danish)

- Axel Olrik. "Tordenguden og hans dreng i lappernes myteverden." Danske Studier 1906, pp. 65–69. (in Danish)