House of Eternity (Ancient Egypt)

In ancient Egypt, the term house of eternity refers to a tomb that consists of a pit, a tomb shaft, or from mudbricks, which were later carved into rocks; or built on open land. Burial sites made of stone were a "sign of immortality", due to the long durability of stone. This was an ideal construction method that could be afforded by only a very few ancient Egyptians, due to its high cost. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the construction of a monument during one's own lifetime represented the most intensive representation with the connection of life; and the concept of living in the afterlife.

| House of Eternity in Hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Kingdom of Egypt |

Per-djet Pr-ḏ.t House of the Eternal Time / | ||||

| Ancient Greek |

Aidioi oikoi Houses of Eternity | ||||

| |||||

The house of eternity was "a place to meet oneself" for the tomb owner and contained decorations portraying the owner's likeness, and the stages of their lives. The owner immortalised themselves with their portrait on the walls of the tomb, along with the inscriptions, to resurrect them in "a new life in later times". The tomb owner depicted their "completed life" in anticipation of their death, which according to their beliefs, was to be removed from this form; in the portrayal of oblivion and mortality.

The tomb owner hoped that through immaculate moral conduct, they would meet their Ka in the afterlife. The house of eternity was the place that enabled the tomb owner to endure unwavering, in the 'eternal life' (djet). With that said, the ancient Egyptians began to spend the most important annual celebrations in the house of eternity.

Mythological connections

The ancient Egyptians believed that life in the mortal world was short in comparison to eternity in the afterlife. They, therefore, had two concepts of time for 'the eternal cycle of life of earth' (neheh - nḥḥ) and 'life in the eternity of the kingdom of the dead' (djet - ḏt). 'Neheh' means a period of time in which something exists, renews and repeats. 'Djet' refers to the future in which earthly life will have ended and everything accomplished in life lives for an indefinite amount of time in Duat.

The sun god Ra was the manifestation of the time called 'neheh', as Ra 'renewed himself every night' and 'was reborn' with the dawn of every day by the sky goddess Nut. Contrary to this, Osiris, as the god of the dead, was the synonym for the time called 'djet'. Osiris', whose appearance was as a mummy, also carried the name of; 'the one who continues to be perfect.' In this respect, neheh, the time of Ra, is the rebirth, and djet, the time of Osiris, is the remembrance.

The 'life goals' of the ancient Egyptians depicted the eternal continuation in the 'Kingdom of Osiris', for which the embalming, mummification and the reading of the judgment of the dead; were required for those who had died. A life lived in moral perfection symbolised 'the good', which was allowed to pass into the afterlife and thus, in the djet after being 'checked by the judgment of the dead.' The house of eternity also functioned as the 'tribunal and mummification hall', constructed according to the principles of the goddess Maat.

The house of eternity as the 'book of life'

The ancient Egyptians lead their lives from birth in preparation for later death. The officials with good earnings and the people working in the temple cults began planning their own house of eternity upon entering into working life. Reserve funds, built from their income, were used for the gradual expansion of their tombs. After laying the foundation stone, the inscriptions telling the stages of life followed. The tradition of the ancient Egyptian house of eternity had its roots in 'result-oriented thinking', which was based on past culture and had no scope for innovation at the religious level.

Contrary to the spiritually innovative progress, which took into consideration life experiences and the further course of continually adapting to new circumstances, the Egyptians saw personal life until death as a perfect outcome for the preparation of the afterlife; in which the completed actions on earth would be repeated. The actions 'to be repeated' had their spiritual foundation in the cult of the dead, which prescribed to living a morally perfect life. Upon the 'successful accomplishments of the tasks in life', the beckoning reward after death was the 'crossing into the holy land.' The point of departure for the crossing into Duat was the house of eternity. Therefore, the construction and the orientation for the tomb was the most important project in the life of an ancient Egyptian.

The house of eternity consisted of the hope in immortality after death. The tomb owner asked himself or herself, in this context, the sorrowful question of whether they were leading a worthy life. The tomb functioned as a mirror, which showed the tomb owner their life in the light of day.

There is a close connection between the house of eternity and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The layout inside of a tomb became a fixed construction design, over a thousand years. The hieroglyphs were primarily linked to the house of eternity and, therefore, there was only a marginal difference in their appearance. Just as the house of eternity was made to last an eternity, so were the hieroglyphs. Even the educated 'ancient Egyptian from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty' should be able to read and understand the tomb inscriptions of their 'ancestors from the First Dynasty.'

The house of eternity functioned according to ancient Egyptian understanding as a 'book of life', which the tomb owner wrote in their role as author. The tomb and the hieroglyphs came together as a 'work of art', which served as a template for future 'houses of eternity' from generation to generation. The hieroglyphs and the house of eternity were based on the foundation of 'cultural memory.' The old systems became hallowed, which prevented the alienation for their own tomb culture. The retention of the old traditions cannot be compared to the 'inability for further development', but it is an expression of the ancient Egyptians' desire for immortality. A Book of Wisdom from the Nineteenth Dynasty states:

They have passed away and have completed their lifetime; all of their contemporaries have fallen into oblivion... However, they created books as heirs and teachings that they wrote themselves... They made their gates and chapels; they have fallen apart. Their priests for the dead have departed, and their alters have become covered with earth... and their names were forgotten, but it is the book that keeps them the memory of them alive.

— Extracts from the Book of Wisdom[1]

Celebration in the house of eternity

(Tomb TT52, Eighteenth Dynasty)

Celebrations in the house of eternity were already being conducted by the time of the Old Kingdom, in which the tomb owner was surrounded by their friends and family. The associated cult of the dead had fully formed by the time of the Fifth Dynasty. Sacrifices and other temple-offerings were brought to the house of eternity for the most important festivals throughout the year. In this era, there was a feast in honour of the tomb owner and for various deities, which was followed by music and dancing.[2] The collapse of the Old Kingdom is connected with a religious addition to the cult of the dead in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. With the addition of the Duat, a new three-levelled view of the world was created in writing, with the 'access to the afterlife of the heavens, and the Duat' through the preparation of the non-sovereign cult of the dead among others; and the new evermore commonly used coffin texts.[3]

The 'earlier funeral feast of the elite' started to reach to a wider audience with the introduction of the Book of the Dead, during the New Kingdom of Egypt. The Beautiful Festival of the Valley is particularly noted during this era. This festival which took place in the house of eternity developed during the Eighteenth Dynasty and became an exuberant feast which included dancing and drinking. A statue or symbol no longer stood in the centre personifying the tomb owner's later life in the Duat, but mainly as a ‘standing sacrificial offering and consecration recipient in life.'[4] During the reign of Akhenaten, in which the cult of Aten was founded, the celebrations in the house of eternity were temporarily suspended. With the start of the Nineteenth Dynasty the earlier traditional structures were again at the forefront, which removed the splendour of the frivolities during the Eighteenth Dynasty; and replaced them with serious rituals.

Houses of eternity

_-_Entrance.jpg.webp)

Only quotations have survived from the work Aegyptiaca ("On the Egyptians") by the Greek historian Hecataeus of Abdera between 320–305 BC, who reported on the life of the Egyptians in Alexandria at the beginning of the Ptolemaic period. Above all, the description of the land of the Nile in the first book of world history Diodorus Siculus is based primarily on Hecataeus. One of his quotes tells about the Houses of Eternity:

The locals give the time they spend living very low value. They called houses for the living 'dosshouses' due to the short time they spend living there. Contrary to this, they place the most value on the time after their death, during which the memory of virtue will preserve them. The tombs of the dead are called 'eternal houses' because the dead spend a never-ending time in the underworld. Therefore, they gave little thought to the earthly materials in their houses, but, on the other hand, it seems that no expense was too high for their tombs.

— Hecataeus of Abdera, quoted by Diodorus Siculus, Bibl. Hist. I 51[5]

The observations of Hecataeus of Abdera mirrored the actual situation in ancient Egypt. The houses of the Egyptians, just as the palaces of the kings, were constructed from air-dried loam bricks, as it was the easiest and cheapest construction material with which to work. Whereas the 'houses of eternity' were built, just as a temple, from stone slabs or were rock-cut tombs.

Mastabas

The mastaba is a type of tomb structure named after the Egyptian-Arabic word for 'stone bench'. Concerning art history, mastabas are part of an evolutionary line that began with the tombs of the elite from the early dynastic period, which lead to the construction of pyramids within royal contexts; and ended at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty in private contexts.

The funeral took place under the building, in a chamber at the end of a shaft. The mastabas of lower courtiers were usually rather simple in comparison and have no niche façade. At the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, the classical mastaba form is no longer a conventional structure. The decoration is mostly reduced to just a false door, while the tomb became gradually more decorated.

Pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are a further development of Nu, which are found at the royal tombs at Abydos, Egypt. The hill shape of the mastabas at Saqqara was also incorporated. From the Third Dynasty, the pyramids served as the burial ground of the King, which developed as a synthesis of the various Upper and Lower Egyptian components of the tomb and valley district.[6] Elements of the tombs and facilities are again found at Saqqara. The large enclosure in Saqqara (Gisr el-Mudir) is said to have served as a stone equivalent of the valley districts of Abydos, as a model for the enclosure of the pyramidal district, as well as the wedge-shaped gallery graves of the Second Dynasty, in Saqqara.

The construction of the Pyramid of Djoser created a new visual appearance for the house of eternity, which was said to have enabled the deceased King or Queen to ascend to a 'human equivalent of the sun,' a rank on par with the sun god Horus. This new philosophy of the kings can be seen alongside the increasing size of the later pyramids.[7] The inside walls of these constructions had relief decorations, such as the those in the Pyramid of Djoser, but were undecorated until the end of the Fifth Dynasty. The paths to the tomb chambers were through tunnels inside of the pyramid.

If the Kings saw themselves as Horus on Earth until the Third Dynasty, then they understood themselves to be 'sons of Ra', with the rising of the sun associated with the god Ra from the time of King Djedefre, Fourth Dynasty. The hierarchical change led to a reduction in the size of the pyramids. The literary work, the Instruction of Hardjedef, which refers to the tombs of the Old Kingdom as houses of eternity, now only exists in fragments. Due to the language, the work can clearly be dated to the Middle Kingdom.[8] It begins with the quote:

Make your home in the west splendid and fit in abundantly from your seat in the necropolis. Accept this; death is minor to us, accept this, for life is mighty. But the house of death serves life.

— Doctrine of Hardjedef[9]

The rest of the text deals with the tomb site. Accordingly, the house of eternity was in the ideal case, a plot to provide the necessary income as an offering. In the Old Kingdom, there was the office 'overseer of the house of eternity'. A Funerary Priest took care of offering the 'revenue of the house of eternity': "This will be more useful to you than a dear son. Promote this more than your heirs. Remember what they say, no heir remembers forever."[10]

Temple tombs

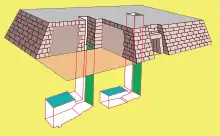

Since the Middle Kingdom, there were temple-like tombs. They were found in all parts of Egypt and are attested to the late period. Some of the temple tombs had a causeway and were surrounded by a wall on the front, where pylons could be found. The mausoleum had a courtyard, optionally decorated with columns. Behind it, there was a cult room with a statue or a door.

The complexes of the Middle Kingdom were partly built in Lisht, in a grand style. In Thebes, there existed smaller variants made of mud bricks. In the New Kingdom, this type of tomb reached its heyday, especially in Saqqara, a large number of these tombs were found and excavated. The walls were often decorated with reliefs and rarely with paintings. Small pyramids were innovated around this time as well.

Shaft and rock tombs

Most ancient Egyptians were buried in simple shafts, or pits, for cost reasons. The Valley of the Kings is where the tombs of the Kings of the New Kingdom (nineteenth and twentieth dynasties), are located in particular. The valley is located in Thebes-West, opposite Karnak, on the edge of the desert and is surrounded by high mountains, namely by the natural rock pyramid, El Qurn ("The Horn"). Almost the entire area of Thebes-West forms a vast necropolis, where, to date, 64 tombs and other mines have been found.

In the Valley of the Queens, three basic types of tombs can be found. The oldest structures are simple, undecorated shaft tombs. These usually had only one chamber, more rarely, one or two auxiliary chambers. The standard tombs generally consist of two large, consecutive rooms. There were up to five auxiliary chambers. The tombs were usually richly decorated.

None of the complexes show the remains of a superstructure which were normally reserved for the cult of the dead. These are probably to be found on the fertile edge and have the form of small temples. Around the time of Thutmose III, the following text was written in tomb TT 131 of the vizier Useramen, who in a few words expresses "result-oriented thinking":

I built myself an excellent grave in my city of abundance of time (neheh). I excellently equipped the site of my tomb from rock in the Eternal Desert ( djet ). May my name last in the mouth of the living, remembering me well in the people after the years to come. This world is a little just for this, but eternity is in the kingdom of the dead.

Literature

- Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. Sonderausgabe. Beck, München 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1.

- Ulrike Fritz: Typologie der Mastabagräber des Alten Reiches. Strukturelle Analyse eines altägyptischen Grabtyps (= Achet – Schriften zur Ägyptologie. A 5). Achet-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-933684-19-6 (Zugleich: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 2000).

- Siegfried Schott: Das schöne Fest vom Wüstentale. Festbräuche einer Totenstadt (= Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur. Abhandlungen der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse. Jg. 1952, Nr. 11, ISSN 0002-2977). Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz 1953.

- Rainer Stadelmann: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder (= Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt. Bd. 30). 3., aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7.

- Kent R. Weeks (Hrsg.): Im Tal der Könige. Von Grabkunst und Totenkult der ägyptischen Herrscher. Fotos von Araldo de Luca. Weltbild, Augsburg 2001, ISBN 3-8289-0586-2.

References

- Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. pp. 484–485.

- Siegfried Schott: Das schöne Fest vom Wüstentale. p. 64 and p. 66.

- Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. p. 169.

- Siegfried Schott: Das schöne Fest vom Wüstentale.

- Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. p. 483

- Mark Lehner: Das erste Weltwunder. Die Geheimnisse der ägyptischen Pyramiden. ECON, Düsseldorf u. a. 1997, ISBN 3-430-15963-6, p. 75 ff.: Die Königsgräber von Abydos.

- W. Helck: Geschichte des alten Ägypten (= Handbuch der Orientalistik. Abt. 1, Bd. 1, 3). Photomechanischer Nachdruck mit Berichtigungen und Ergänzungen. Brill, Leiden 1981, ISBN 90-04-06497-4, p. 45–46.

- Günter Burkhard, Heinz J. Thissen: Einführung in die altägyptische Literaturgeschichte. Band 1: Altes und Mittleres Reich (= Einführung und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie. Bd. 1). 2. Auflage. LIT, Münster u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-6132-2, p. 81.

- Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. p. 481

- Hellmut Brunner: Altägyptische Weisheit. Lehren für das Leben (= Die Bibliothek der alten Welt. Reihe: Der Alte Orient. Bd. 6). Artemis, Zürich u. a. 1988, ISBN 3-7608-3683-6, S. 103.