Huaca de la Luna

Huaca de la Luna ("Temple or Shrine of the Moon") is a large adobe brick structure built mainly by the Moche people of northern Peru.[1] Along with the Huaca del Sol, the Huaca de la Luna is part of Huacas de Moche, which is the remains of an ancient Moche capital city called Cerro Blanco, by the volcanic peak of the same name.

| Huaca de la Luna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Nearest city | |

| Coordinates | 8°8′5.93″S 78°59′27.40″W |

| Established | Mochica era |

Background

The Huacas de Moche site is located 4 km outside the modern city of Trujillo, near the mouth of the Moche River valley. The Huaca de la Luna, although it is the smaller of the two huacas at the site, has yielded the most archaeological information. The Huaca del Sol was partially destroyed and looted by Spanish conquistadors in the seventeenth century, while the Huaca de la Luna was left relatively untouched. Archeologists believe that the Huaca del Sol may have served for administrative, military, and residential functions, as well as a burial mound for the Moche elite. The Huaca de la Luna served primarily a ceremonial and religious function, although it contains burials as well.

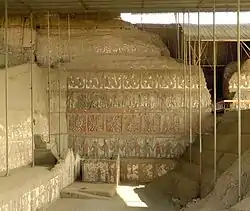

Today, the Huaca de la Luna is colored the soft brown of its adobe brickwork. At the time of construction, it was decorated in registers of murals that were painted in black, bright red, sky blue, white, and yellow. The sun and weather has since utterly faded these murals away. Inside the Huaca are other murals created in earlier phases of construction. Many of these depict a deity now known as Ayapec. Ayapec is a Muchik word translating as all knowing (note: the name "Ayapec" or "Ai - Apaec" is a modern artifact. When Larco Hoyle asked his workers about how would be "the highest god" in Muchik, they answered him that it would be "Ai - Apaec". For that reason Larco Hoyle stated, that it was the name for the Moche supreme deity. He ignored also that in the pre-Columbian Moche Valley the spoken language was not Muchik, but Quingnam). "Wrinkle-Face" is the name given to another deity by the later Inca because of the deity's appearance.

Many of the later bricks used in the structure bear one of more than 100 different markings, perhaps corresponding to groups of laborers from different communities. Maybe each "team" was assigned a mark to put on their bricks and these were used to count the number of bricks laid for financial as well as (presumably) competitive purposes.

The Huaca de la Luna is a large complex of three main platforms, each one serving a different function. The northernmost platform, at one time brightly decorated with a variety of murals and reliefs, was destroyed by looters. The surviving central and southern platforms have been the focus of most excavations. The central platform has yielded multiple high-status burials interred with a variety of fine ceramics, suggesting that it was used as a burial ground for the Moche religious elite. The grave goods found at the Huaca del Sol suggest it may have been used for the interment of political rulers.

The eastern platform, black rock, and adjacent patios were the sites of human sacrifice rituals. These are depicted in a variety of Moche graphic representations, most notably painted ceramics. After the sacrifice, bodies of victims would be hurled over the side of the Huaca and left exposed in the patios. Researchers have discovered multiple skeletons of adult males at the foot of the rock, all of whom show signs of trauma, usually a severe blow to the head, as the cause of death.

The World Monuments Fund has been working at Huaca de la Luna to support needed conservation work. This includes ongoing assessments, documentation, stabilization, and consolidation of excavated architectural and decorative elements.

See also

References

- Benson, E.P.; Cook, A.G. (2001). Ritual sacrifice in ancient Peru. University of Texas Press. p. 211.

- Art of the Andes, from Chavin to Inca. Rebecca Stone Miller, Thames and Hudson, 1995.

- The Incas and their Ancestors. Michael E. Moseley, Thames and Hudson, 1992.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huaca de la Luna. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huacas. |