Hudibras

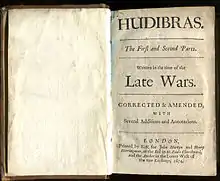

Hudibras (/ˈhjuːdɪbræs/)[1] is an English mock-heroic narrative poem from the 17th century written by Samuel Butler. Published in the aftermath of the English Civil War, it is a scathing satire of Puritanism and the Parliamentarian cause from a Royalist perspective.

Purpose

The work is a satirical polemic upon Roundheads, Puritans, Presbyterians and many of the other factions involved in the English Civil War. The work was begun, according to the title page, during the civil war and published in three parts in 1663, 1664 and 1678, with the first edition encompassing all three parts in 1684.[2] The Mercurius Aulicus (an early newspaper of the time) reported an unauthorised edition of the first part was already in print in early 1662.[3]

Published only four years after Charles II had been restored to the throne and the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell being completely over, the poem found an appreciative audience. The satire is not balanced as Butler was fiercely royalist and only the parliamentarian side are singled out for ridicule. Butler also uses the work to parody some of the dreadful poetry of the time.

The epic tells the story of Sir Hudibras, a knight errant who is described dramatically and with laudatory praise that is so thickly applied as to be absurd, revealing the conceited and arrogant person visible beneath. He is praised for his knowledge of logic, despite appearing stupid throughout, but it is his religious fervour which is mainly attacked:

For his Religion, it was fit

To match his Learning and his Wit:

'Twas Presbyterian true blew;

For he was of that stubborn Crew

Of Errant Saints, whom all men grant

To be the true Church Militant:

Such as do build their Faith upon

The holy text of Pike and Gun;

Decide all Controversies by

Infallible Artillery;

And prove their Doctrine Orthodox

By Apostolic Blows and Knocks;

Call Fire and Sword and Desolation,

A godly-thorough-Reformation,

Which always must be carry'd on,

And still be doing, never done:

As if Religion were intended

For nothing else but to be mended.[4]— First Part, Canto I, lines 189-206

His squire, Ralpho, is of a similar stamp but makes no claim to great learning, knowing all there is to know from his religion or "new-light", as he calls it. Butler satirises the competing factions at the time of the Protectorate by the constant bickering of these two principal characters whose religious opinions should unite them.

These are fawning but barbed portraits and are thought to represent personalities of the times but the actual analogues are, now as then, debatable. "A Key to Hudibras" printed with one of the work's editions (1709) and ascribed to Roger L'Estrange names Sir Samuel Luke as the model for Hudibras. Certainly, the mention of Mamaluke in the poem makes this possible, although Butler suggests Hudibras is from the West Country, making Henry Rosewell a candidate. The witchfinder Matthew Hopkins, John Desborough, parliamentarian general, and William Prynne, lawyer, all make appearances, and the character of Sidrophel is variously seen as either William Lilly or Paul Neale.

Structure

Butler is clearly influenced by Rabelais and particularly Cervantes' Don Quixote. But whereas in Cervantes, the noble knight although being mocked is supposed to draw readers' sympathies, Hudibras is offered nothing but derision.

The title comes from the name of a knight in Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene who is described as "not so good of deeds as great of name" and "more huge in strength than wise in work". Spenser in turn probably got the name from the legendary king of the Britons, Rud Hud Hudibras.

Hudibras was written in an iambic tetrameter in closed couplets, with surprising feminine rhymes. The dramatic meter portends tales of dramatic deeds, but the subject matter and the unusual rhymes undercut its importance. This verse form is now referred to as Hudibrastic. Consider the following from the opening of the poem, where the English Civil War is described thus:

When civil fury first grew high,

And men fell out they knew not why,

When hard Words, Jealousies, and Fears,

Set Folks together by the Ears,

And made them fight, like mad or drunk,

For Dame Religion, as for Punk;

Whose honesty they all durst swear for,

Though not a man of them knew wherefore:

When Gospel-Trumpeter surrounded,

With long-ear'd rout, to Battle sounded,

And Pulpit, Drum Ecclesiastick,

Was beat with fist, instead of a stick:

Then did Sir Knight abandon dwelling,

And out he rode a Colonelling.[5]— First Part, Canto I, lines 1-14

The work was published in three parts, each divided into three cantos with some additional heroic epistles. It is possible that a fourth part was planned, which would have given the work twelve parts in imitation of Virgil's Aeneid.

Plot

The knight and his squire sally forth and come upon some people bear-baiting. After deciding that this is anti-Christian they attack the baiters and capture one after defeating the bear. The defeated group of bear-baiters then rallies and renews the attack, capturing the knight and his squire. While in the stocks the pair argue on religion.

The second part describes how the knight's imprisoned condition is reported by Fame to a widow Hudibras has been wooing, who then comes to see him. With a captive audience, she complains that he does not really love her and he ends up promising to flagellate himself if she frees him. Once free he regrets his promise and debates with Ralpho how to avoid his fate, with Ralpho suggesting that oath breaking is next to saintliness:

For, breaking of an Oath, and Lying,

Is but a kind of Self-denying,

A Saint-like virtue, and from hence,

Some have broke Oaths by Providence:

Some, to the Glory of the Lord,

Perjur'd themselves, and broke their word:[6]— Second Part, Canto II, lines 133-138

Hudibras then tries to convince Ralpho of the nobility of accepting the beating in his stead but he declines the offer. They are interrupted by a skimmington, a procession where women are celebrated and men made fools. After haranguing the crowd for their lewdness, the knight is pelted with rotten eggs and chased away.

He decides to visit an astrologer, Sidrophel, to ask him how he should woo the widow but they get into an argument and after a fight the knight and squire run off in different directions believing they have killed Sidrophel.

The third part was published 14 years after the first two and is considerably different from the first parts. It picks up from where the second left off with Hudibras going to the widow's house to explain the details of the whipping he had promised to give himself but Ralpho had got there first and told her what had actually happened. Suddenly a group rushes in and gives him a beating and supposing them to be spirits from Sidrophel, rather than hired by the widow, confesses his sins and by extension the sins of the Puritans. Hudibras then visits a lawyer—the profession Butler trained in and one he is well able to satirise—who convinces him to write a letter to the widow. The poem ends with their exchange of letters in which the knight's arguments are rebuffed by the widow.

Before the visit to the lawyer there is a digression of an entire canto in which much fun is had at the events after Oliver Cromwell's death. The succession of his son Richard Cromwell and the squabbles of factions such as the Fifth Monarchists are told with no veil of fiction and no mention of Sir Hudibras.

Significance

Hudibras was an extremely popular work with pirate copies and a spurious second part being issued before Butler could produce his genuine second part in 1664. It was highly praised with Voltaire in his Letters on the English saying "I never found so much wit in one single book". One reader though was distinctly unimpressed. On 26 December 1662 Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that he bought Hudibras, but, despite its being extremely popular at the time, he admitted finding no humour in it and selling it the same day. Two months later he bought it again to try to find what he was missing. He still found nothing funny about it, due to his finding its treatment of Puritans too vicious and being insensitive to the humour of the rhymes.

The mock heroic epic and its jaunty verse form known as Hudibrastic became the standard of satire for some time after that with at least twenty-seven direct imitations being produced. Of the most famous was Ned Ward and his Hudibras Redivivus with Samuel Wesley father of John Wesley emulating the work.

A half century after the last part was written a new edition was published in 1727, with engraved illustrations by William Hogarth, who later became one of the foremost artists of the day. The work remained popular for several centuries as a warning against the zealotry during the Civil War period of English history although it has lately gone out of fashion.

In his poem, Butler coined the phrase "Spare the rod and spoil the child," probably a modification of a Biblical injunction about child-rearing given in Book of Proverbs: "He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes" (Proverbs 13:24). In the context of Hudibras the phrase is a bawdy metaphor suggesting the best way to curtail amorous passions or, through double entendre, to prevent conception:

If Matrimony and Hanging go

By Dest'ny, why not Whipping too?

What med'cine else can cure the fits

Of Lovers when they lose their Wits?

Love is a Boy by Poets stil'd,

Then Spare the Rod, and spill the Child.[7]— Second Part, Canto I, lines 839-844

One couplet was widely quoted through the end of the nineteenth century as an illustration of the fact that some people just want action and excitement, never mind what:

Doubtless the pleasure is as great

Of being cheated, as to cheat.[8]— Second Part, Canto III, lines 1-2

References

- Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- Butler, Samuel (1835). Hudibras; with notes by Treadway Russell Nash. Oxford University. p. vii.

- Butler, Samuel (1905). Waller, A. R. (Alfred Rayney) (ed.). Hudibras; written in the time of the late wars;. Cambridge University Press. p. 8.

- Butler, Samuel (1905). Waller, A. R. (Alfred Rayney) (ed.). Hudibras; written in the time of the late wars;. Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- Butler, Samuel (1905). Waller, A. R. (Alfred Rayney) (ed.). Hudibras; written in the time of the late wars;. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132-133.

- Butler, Samuel (1905). Waller, A. R. (Alfred Rayney) (ed.). Hudibras; written in the time of the late wars;. Cambridge University Press. p. 126.

- Butler, Samuel (1905). Waller, A. R. (Alfred Rayney) (ed.). Hudibras; written in the time of the late wars;. Cambridge University Press. p. 152.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Media related to Hudibras at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hudibras at Wikimedia Commons- Butler, Samuel (1835). Hudibras; with notes by T.R. Nash. London: Oxford University.

- Butler, Samuel (1805). Hudibras. London: republished by Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- e-text of Hudibras