Hyperdiffusionism

Hyperdiffusionism is a pseudoarchaeological hypothesis suggesting that certain historical technologies or ideas originated with a single people or civilization before their adoption by other cultures. Thus, all great civilizations that share similar cultural practices, such as construction of pyramids, derived them from a single common progenitor.[1] According to its proponents, examples of hyperdiffusion can be found in religious practices, cultural technologies, megalithic monuments, and lost ancient civilizations.

The idea of hyperdiffusionism differs in several ways from trans-cultural diffusion, one being that hyperdiffusionism is usually not testable due to its pseudo-scientific nature.[2]:255–56 Additionally, unlike trans-cultural diffusion, hyperdiffusionism does not use trading and cultural networks to explain the expansion of a society within a single culture; instead, hyperdiffusionists claim that all major cultural innovations and societies derive from one (usually lost) ancient civilization.[2]:224–32 Ergo, the Tucson artifacts derive from ancient Rome, carried by the "Romans who came across the Atlantic and then overland to Arizona;" this is believed because the artifacts resembled known ancient Roman artifacts.[2]:246

Mainstream archeologists regard the hyperdiffusionism hypothesis as pseudoarchaeology.[3]

Some key proponents

Charles Hapgood

In Charles Hapgood's book Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, he concludes that ancient land formations gave way to hyperdiffusionism and the diffusion "of a true culture."[4] This culture could have been more advanced than that of Egypt or Greece because it was the foundation of a worldwide culture. Hapgood also suggests that the Three-age system of archeology is irrelevant due to primitive cultures co-existing with modern societies.[4]:193–94

Grafton Elliot Smith

Heliolithic Culture, as Grafton Elliot Smith refers to it, consists of cultural practices such as megaliths. Similar designs and methods of construction of such pieces have what seem like a linear geographical distribution.[5] These heliolithic cultures can refer to religious customs that share distinctive practices, such as the worship of a Solar Deity. As this trope is seen in numerous belief systems, Smith believes it is diffused from one ancient civilization.[5]:132

Early Man Distribution refers to Smith's implication that Man derived from "six well-defined types of mankind," who comprise the sources for Earth's population.[6] The six types of mankind are the Aboriginal Australians, Negros, Mongols, and the Mediterranean, Alpine, and Nordic races.[6]:15 Recently this classification has been labeled as scientific racism.

Barry Fell

Mystery Hill, or America's Stonehenge, is the site which Barry Fell refers to as the primary basis of his hypothesis that ancient Celts once populated New England.[7] Mystery Hill, Fell believes, was a place of worship for the Celts and Phoenician mariners.[7]:91 These ancient mariners, more commonly known as the Druids, are said to have populated Europe at the same time. He hypothesizes that they were the ancient settlers of North America. Also, he believes that what he describes as inscriptions on stone and tablet artifacts from this site are in an ancient language derived from common sources of the Goidelic languages.[7]:92

These three authors describe hyperdiffusionism as the driving force behind the apparent cultural similarities and population distribution among all civilizations. Hapgood's hypothesis states that one specific civilization is responsible for similar cultural practices in all other civilizations. Smith says that religions are proof of hyperdiffusionism, as similar worship ceremonies and symbols recur in geographically separated societies. Also, Smith believes that the Earth's population is made up of six types of humans, who diffused across the Earth's continents by virtue of their skin color.[6]:47–48 Finally, Fell asserts that ancient mariners, such as Druids and Phoenicians, traveled from Europe and comprised the early population of ancient America.

Carl Whiting Bishop

Carl Whiting Bishop in the 1930s and the 1940s produced a series of articles arguing hyperdiffusionism in explaining the expansion of technology into China. Among the scholars influenced by Bishop were Owen Lattimore, who was intrigued by Bishop's emphasis on geography as a shaping factor in Chinese civilization and his emphasis on field work rather than library research.[8]

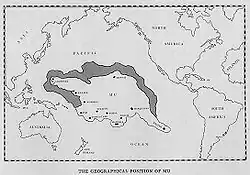

Lost civilizations

A common hyperdiffusionist hypothesis is that the similarities among disparate civilizations were inherited from the civilization of a lost continent, either Atlantis or Lemuria, which has since sunk into the sea. Sometimes Egypt is taken to be an intermediate civilization that inherited its culture from the lost continent and in turn passed it on to other civilizations. According to G. Elliot Smith, Egypt was the source of civilization for Asia, India, China, the Pacific, and eventually America.[5]:45

Mayans

According to Hapgood, the pyramids in South America and Mexico may be indicative of cultural practices shared with ancient Egyptian civilization.[4]:200 He theorized that the ancient Maya were strongly influenced by the diffusion of ancient Egyptian social and political cultures,[9] and that they became a civilized culture due to the migration of citizens from Atlantis after that island sank.[10] For example, he says "How did the Mayans achieve such precise results...the knowledge may have, of course, been derived by the Babylonians or the Egyptians".[4]:198 It is also said that Mayan artifacts resemble those of a classical culture, possibly Greece.[1]:147 This plays into Plato's Account of the ancient battle for Atlantis, which led to the downfall of the civilization.

Religion and mythology

Hapgood finds evidence of ancient Egyptian "expression" in the writings of Hinduism and Buddhism. He notes that in these writings there are aappear deities that are similar to those worshiped throughout the world. Furthermore, there are myths and creation stories that are said to have a common origin in Egypt.[4]:204–5 G. Elliot Smith sees Mummification as a prime example of how religious customs prove the diffusion of a single ancient culture.[5]:21 He believes that only an advanced civilization, such as Egypt, could create such a peculiar belief, and that it then spread by way of ancient mariners.[5]:133–34

Critiques

Ethnocentrism and racism

Michael Shermer states that using racial taxonomy in order to make abstract assertions of racial superiority is another expression of ethnocentrism.[11]:248 He asks, "how can we 'pigeonhole' blacks as permissive or whites as intelligent when such categories...are actually best described as a continuum?"[11]:250 Shermer claims that the belief that one race and/or culture is superior to another defeats the purpose of cultural evolution, and that we cannot dismiss evidence of blending inheritance among all cultures.[11]:247–51 Shermer uses The Bell Curve by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray as an example of pigeonholing; Herrnstein and Murray try to pigeonhole civilizations into racial categories based on flawed measures of intelligence.[11]:242–44

Alice Beck Kehoe says that diffusionism is a "grossly racist ideology".[12]:144 Although she agrees that diffusion of culture can occur through contact and trading, she disagrees with the theory that all civilization came from one superior ancient society.[12]:148

Pseudoarchaeology

Critical thinker and archaeologist Stephen Williams uses the phrase "Fantastic Archaeology" to describe the archeological theories and discoveries which he defines as "fanciful archaeological interpretations".[2]:12 These interpretations usually lack artifacts, data, and testable theories to back up the claims made.

Hyperdiffusionism versus Independent Invention

Kehoe explores the "independent invention" of works and techniques using the example of boats. Ancient peoples could have used their boat technology to make contact with new civilizations and exchange ideas. Moreover, the use of boats is a testable theory, which can be evaluated by recreating voyages in certain kinds of vessels, unlike hyperdiffusionism.[12]:158 Kehoe concludes with the theory of transoceanic contact and makes clear that she is not asserting a specific theory of how and when cultures diffused and blended, but is instead offering a plausible, and testable, example of how civilizational similarities may have arisen without hyperdiffusionism, namely by independent invention and maritime contact.[12]:169

Alexander Goldenweiser in Culture: The Diffusion Controversy stated that there are reasons for believing that culture may arise independently rather than being transmitted. In addition, Goldenweiser insists that behavior is primitive and that cultural similarities may arise simply because they are reflections of adaptive traits that all human beings have evolved. Goldenweiser disagrees with the theory of hyperdiffusionism, stating that "culture is not contagious"[13]:104 and that the data fails to support the theory.[13]:100–106

Methods

Stephen Williams in his chapter "Across The Sea They Came" introduced a few hyperdiffusionists, their discoveries, and how they "tested" artifacts, beginning with Harold S. Gladwin who made his "fantastic" discoveries at an Arizona Pueblo site, Gila Pueblo Archaeological Foundation. Gladwin favored the diffusion theories which later influenced his methodologies for dating the artifacts at the site. This belief led him to ignore the data that was found at the Folsom Site in his chronology as it made his "Man descended from Asia into the New World" theory impossible.[2]:230

The section continues with Cyclone Covey and Thomas W. Bent, specifically their publications on the Tucson Artifacts and their theory that ancient Romans traveled to Arizona. Williams pokes fun at this theory in his book Fantastic Archaeology, and criticizes the authors for failing to explain exactly how and why these artifacts were found in Arizona, and focusing their attention instead only on the artifacts themselves and their similarities to Roman artificats.[2]:240

Concluding, Williams points out in the chapter how hyperdiffusionists fail to recognize solid archaeological research methods and/or ignore conflicting data and contextual evidence. They are "tailoring their finds with any similar chronology or in-depth linguistic analysis that fits into their scenarios".[2]:255–56

See also

Notes

- Fagan, Garrett G., ed. (2006). Archaeological Fantasies. Oxford, England: Routledge. pp. 362–367. ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8.

- Williams, Stephen (1991). Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 224–257. ISBN 0-8122-1312-2.

- Moshenska, Gabriel (2017), Alternative archaeologies, UCL Press, pp. 122–137, ISBN 978-1-911576-43-3, JSTOR j.ctt1vxm8r7.13

- Hapgood, Charles H. (1966). Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings. Philadelphia: Chilton Company. pp. 193–206.

- Smith, G. Elliot (1929). The Migrations of Early Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. OCLC 1868131.

- Smith, G. Elliot (1931). The Evolution of Man. London: Ernest Benn Limited. pp. 13–47. OCLC 637203360.

- Fell, Barry (1976). Ancient Settlers in the New World. New York: Quadrangle. pp. 81–92. ISBN 0-8129-0624-1.

- Newman, Robert P. (1992), Owen Lattimore and the 'Loss' of China, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07388-3, p. 24

- Webster, David (2006), "The Mystique of the Ancient Maya", in Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.), Archaeological Fantasies, Oxford: Routledge, pp. 129–154, 978-0-415-30593-8

- Hale, Christopher (2006), "The Atlantean Box", in Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.), Archaeological Fantasies, Oxford: Routledge, pp. 235–59, ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8

- Shermer, Michael (1997). Why People Believe Weird Things (2002 ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-8050-7089-7.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck (2008). Controversies in Archaeology. California: Left Coast Press, INC. pp. 140–172. ISBN 978-1-59874-062-2.

- Goldenweiser, Alexander (1927). Culture: The Diffusion Controversy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 99–106. OCLC 1499530.