Ice hockey stick

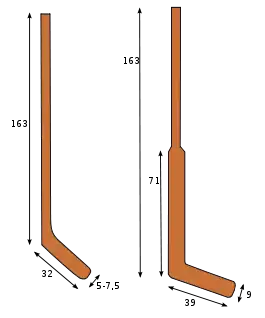

An ice hockey stick is a piece of equipment used in ice hockey to shoot, pass, and carry the puck across the ice. Ice hockey sticks are approximately 150–200 cm long, composed of a long, slender shaft with a flat extension at one end called the blade. National Hockey League (NHL) sticks are up to 63 inches (160 cm) long.[1] The blade is the part of the stick used to contact the puck, and is typically 25 to 40 cm long. Stick dimensions can vary widely, as they are usually built to suit a particular player's size and preference. The blade is positioned at roughly a 135° angle from the axis of the shaft, giving the stick a partly 'L-shaped' appearance. The shaft of the stick is fairly rigid, but is slightly elastic to improve shot performance.

The blade is slightly curved to aid control of the puck, especially in shooting. The direction of the curve depends on the side of the body the player wields the stick on.

The goaltender has a slightly modified stick. The lower part of the stick is wider, the angle is smaller, and the blade is slightly curved towards the direction of the play. New goaltender sticks also are made of the same composite technology as used in regular sticks.

History

The oldest known hockey stick dates to the mid-1830s; it was made by William "Dilly" Moffatt (born 1829) from sugar maple wood and is now owned by the Canadian Museum of History.[2] In 2006, a stick made in the 1850s, at the time the oldest known, was sold at auction for $2.2 million; it had been appraised at US$4.25 million.[3]

The Moffatt stick may have been made by Mi'kmaqs. Starting in the 18th century, there are numerous references to the Mi'kmaq people of Nova Scotia playing ice hockey, and starting in the 19th century, there are claims that they invented the ice hockey stick.[4] In the mid-19th century, the Starr Manufacturing Company began to sell Mic-Mac hockey sticks nationally and internationally.[5] Through the first decade of the 20th century, it was the best-selling hockey stick in Canada. By 1903, apart from farming, producing them was the primary occupation of the Mi'kmaq on reserves throughout Nova Scotia, particularly Shubenacadie, Indian Brook and Millbrook.[5] In 1927 the department of Indian Affairs for Nova Scotia identified that the Mi'kmaq remained the "experts" at making hockey sticks.[6] Mi'kmaq continued to make hockey sticks until the 1930s.[7]

Hockey sticks were mostly made from the maple or willow trees, which was also a common choice for golf club shafts and wooden tools. However, as hornbeam supplies diminished, it became more cost effective to use other hardwoods, such as yellow birch and ash. Ash gradually became the preferred medium, and by the 1920s an ash hockey stick crafted from a single piece of wood was the type most commonly used. These early sticks were extremely heavy and not very forgiving, although they were extremely durable (Hall of Famer Moose Johnson famously used the same extra-long stick, which gave him a 99-inch (2,500 mm) reach, his entire career).

There were only a handful of major developments in hockey stick technology between the 1920s and the 2000s. Foremost among these was creation of the laminated stick in the 1940s, where layers of wood were glued together and sandwiched to create a more flexible and durable design. In the 1960s, companies began adding another lamination of fiberglass or other such synthetic compound as a coating, which further added to the durability and usability of the stick. Also in the 1960s, players began curving the blade of the stick, which dramatically changed the physics affecting players' shots.

In the 1970s, cricket and baseball bat manufacturers began experimenting with lightweight steel alloys as a replacement for the traditional willow or ash bat. Hockey stick designers followed suit in the early 1980s, introducing first a single piece all-aluminum stick. This design was not popular, as the stiff aluminum did not have the proper "feel", and so a design featuring an aluminum shaft and a removable, replaceable wooden blade was tried. This became very popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s, challenging the prevalence of the traditional wooden stick for the first time.

In recent years, the aluminum stick, as well as its wooden counterpart, have largely been replaced by more advanced composite designs. Common building materials include fiberglass and carbon fiber. Composite sticks generally weigh less than their aluminum forebears, and they can be manufactured with more consistent (and varied) physical properties than their wooden counterparts. They are, however, considerably more expensive than wooden sticks, and are not as durable as the older aluminum sticks.

Materials

Over the last two decades, there have been tremendous advances in the material technology used to create hockey sticks. The vast majority of sticks are made with one or more of the following materials:

Carbon Fiber

Carbon fiber has become by far the most common building material for sticks used in the NHL. Carbon fiber sticks were originally sold as shafts alone, much like their aluminum counterparts but nowadays, most hockey sticks are "one piece" sticks. The first company to successfully develop, produce and market "one piece" carbon fiber composite sticks was Composite Busch SA [10] out of Switzerland in 1992.

Carbon fiber sticks are ideal due to their light weight and favorable mechanical characteristics. They are generally accepted to be able to store and release elastic potential energy predictably and efficiently,[11] however, There is ongoing debate over whether the mechanical characteristics of composite sticks makes for more powerful shots.[12]

Compared to other materials, carbon fiber sticks tend to be break more easily and cost more.

Fiberglass

Fiberglass was the first composite stick material, initially used with wood. Some sticks made solely from fiberglass have been produced but today, fiberglass is most commonly used as a composite with other materials, such as wood, carbon fiber, and/or kevlar.

Wood

Wooden sticks are usually constructed by laminating multiple types of wood into a high quality plywood, then coating the stick and blade with thin plastic or fiberglass. Some manufacturers use fiberglass as a laminate between wood layers. Today in the NHL, almost no players still use wooden sticks.

The main advantage that wooden sticks enjoy today is their low cost. This makes them a popular choice for street hockey. Their main disadvantage that wooden sticks suffer from is their relative inconsistency.[13][14] Wood has a tendency to warp, and over time its flex and stiffness properties will change. Additionally, being a natural material, wood also creates variations in production (even between identical patterns).

Aluminum

Aluminum sticks were the first non-wood sticks to appear. Most aluminum sticks consist of a shaft made of an aluminum alloy and a wooden blade or composite blade, which is held in the shaft by glue and the compression of the shaft itself. There was a brief period in the 1990s when the majority of NHL players used aluminum sticks, but today nearly all players use composite sticks.[15]

The main advantage aluminum sticks enjoy is their unparalleled durability. It is fairly rare for an aluminum shaft to be broken or damaged, even at the professional level, and since the blades can be easily replaced, a shaft will typically last for a relatively long period of time. Aluminum sticks will not suffer wear or warping like a wooden stick, and they can be manufactured with high consistency. Aluminum sticks, however, are not as elastic as other materials.

Properties

Lie

The lie of a stick refers to the angle between the shaft and the blade. A lie value of 5 corresponds to a 135° angle, and each additional lie value corresponds to a 2° smaller angle.[16] With the bottom of the blade flat on the ice, a higher lie value corresponds to a more upright shaft. Typical values range from 5 to 7; most sticks now are near 5.5. Goalie sticks typically have a lie between 11 and 15.[17]

Players usually seek a lie that will put the blade flat on the ice while they are in their typical skating stance. Hall of Fame center Wayne Gretzky, for example, used a stick with a low lie to correspond with his deep skating crouch and shorter height, whereas Hall of Fame defenceman Rod Langway used a stick with a very high lie number as he was very tall and tended to skate in a very upright position.

Flex

Hockey stick shafts, much like golf club shafts, are highly flexible, and this flexibility is a key component in their performance. Flex, bend, stiffness, and whip are all terms used to describe the amount force required to bend a given stick shaft a certain amount.

With most composite and aluminum sticks, their flex characteristic is correlated numerically. This number, which ranges from 40 through 160, is printed on the stick and corresponds to the amount of force (in pounds-force) that it takes to deflect or bend the shaft one inch. For example, 100 pounds-force (440 N) is required to bend the shaft 1 inch (2.5 cm) and would be labelled "100 flex". The flex rating of a stick applies to its original length and increases if it is cut to a shorter length.

Stick flex is viewed as a very important characteristic by most players. Commonly, defencemen seek stiffer flex shafts, as their greater stiffness imparts more force on slap shots and improves stick-checking. Forwards will commonly seek more flexible shafts, as they require less force to bend and are thus better suited to create quick and accurate wrist shots, as well as improving passing and stickhandling.

Flex is also correlated to player strength; stronger players will often prefer stiffer flexes, as they have a sufficient amount of strength to fully bend (and thus maximize potential energy) using such shafts, whereas younger players and players with less strength will generally have more success using more flexible shafts which they are capable of bending to their optimal degree.

Blade shape

Until the early 1960s, hockey stick blades[18] were typically not curved. However, in the late 1950s, New York Rangers center Andy Bathgate began experimenting with "breaking" his stick blades to impart a curve, which he found made his slap shots behave in highly erratic ways. Soon after Chicago Black Hawks forwards Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull stumbled onto the "broken blade", and subsequently began asking their stick manufacturers to create sticks with pre-curved blades.

Soon after, much of the NHL, and Hull in particular, became a proponents of the "banana blade", or stick with extreme amounts (often up to 3 inches (76 mm)) of curve in the blade. These curves made slap shots behave very erratically, and in an era in which goalies did not wear masks, this eventually became an unacceptable danger. By 1967, the NHL began to limit the amount of curve a stick blade could legally have. In the NHL today, the legal limit is 19 mm, or 3⁄4 of an inch.

Much like the shaft's flex, a blade's shape is a very important characteristic of a stick's performance. There are three primary variables in blade design: curve, face angle, and toe.

The curve refers to the basic amount the blade curves from toe to heel, as well as the part of the blade where that curve is located. A "toe curve" means that the curve is concentrated near the toe of the blade, and it is usually preferred by forwards, who seek better puckhandling and more accurate wrist shots. A "heel curve" is generally better for slap shots, and is thus used more by defencemen.

Face angle is the angle between the ice surface and the front surface of the blade (this characteristic is comparable to the difference between the different irons in golf). A more "open" blade means that the face of the blade is turned up more sharply, and thus will cause a higher trajectory than a "closed" face angle.

The toe shape refers to the basic shape of the end of the blade, and it is typically either round or square. Square toes make it easier to pull a puck off the boards or to do "toe drags" (stickhandling moves using the toe of the blade), whereas round toes make it easier to "flip" the puck, and also offer slight advantages in basic puckhandling.

Blades also differ in length and thickness, based on player preference.

Illegal curves

The curve of a blade is limited at most levels of competitive hockey, generally to an amount between 1⁄2 and 3⁄4 inch (13 and 19 mm). Hasty measurements can be made by attempting to roll a dime under the j blade placed face down on the ice, but accurate measurements require a "stick gauge" which measures curve precisely.[19] Currently, the NHL limits blade curvature to 3⁄4 inch (19 mm).[19] Being caught using an illegal stick is typically punished with a two-minute minor penalty.[19]

The genesis for this rule was the "banana blade" of the 1960s. At the height of this era, players would often simply cross the blue line and let fly with a slap shot, hoping that the bizarre behavior of the puck would beat the goaltender. In this era, goaltenders were irritated by the danger such wild shots posed to them and in response, the NHL began gradually reducing the amount of curve a blade could legally have.

In the modern game, the emphasis on shooting accuracy has largely eliminated any preference for extreme blade curves. However, hockey still retains illegal stick rules, which has become a cause of debate.[19] The argument is that since blade curvature does not impart any significant advantage, that penalizing it is unnecessary. Additionally, coaches have used the "illegal equipment" penalty at key moments in games to win a power play, and in some cases, swing the momentum of an entire series, including the 1993 Stanley Cup Finals.

Tape

Technique

See also

- Field hockey stick

- Ramp function, often called a "hockey stick" due to similar shape

- Hockey stick graph

- A square jawline is sometimes called "hockey chin" or "hockey stick jawline"

References

- "NHL players mighty particular when it comes to their sticks - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- Adams, James (January 9, 2015). "World's oldest known hockey stick tells a very Canadian tale". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- "Hockey stick billed as oldest ever nets $2.2 million". The Globe and Mail (revised April 7, 2009). Canadian Press. December 22, 2006.

- Cuthbertson, Brian (2005). "The Starr Manufacturing Company: Skate Exporter to the World". Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 8: 60.

- Cuthbertson, p. 61.

- Cuthbertson, p. 73.

- Cuthbertson, p. 63.

- Cotsonicka, Nicholas J. (June 18, 2013). "Bigger and better: There's nobody in the NHL like Bruins captain Zdeno Chara". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Staff, Cup of Chowder (May 17, 2018). "Geared up: What kind of equipment do the Boston Bruins use?". Stanley Cup of Chowder. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- "Compostie Busch SA".

- News; Canada (November 18, 2012). "Who killed the wooden hockey stick? | National Post". Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- Laliberte, David J. (2009). "Biomechanics of Ice Hockey Slap Shots: Which Stick Is Best?". The Sport Journal. 12 (1). ISSN 1543-9518. Archived from the original on August 6, 2009.

- Farber, Michael; Kennedy, Kostya; Bechtel, Mark (December 23, 2002). "Out Of The Woods". Sports Illustrated (Subscription necessary). 97 (25). p. 26. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016.

- "Companies Defend New-Age Hockey Sticks; Breakage Seen During NHL Playoffs Gives False Impression, Easton Vice-President Says". The Record (Waterloo Region).

- "What is a hockey stick made of?". www.prostockhockey.com. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- "Hockey Stick Sizing Guide at prohockeystuff.com". Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "How To Buy a Hockey Stick at MVP.com". Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Ice Hockey Stick Blades".

- National Hockey League Official Rules (PDF) (2007-2008 ed.). Chicago, IL: Triumph Books. 2007. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-894801-12-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2008.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ice hockey sticks. |