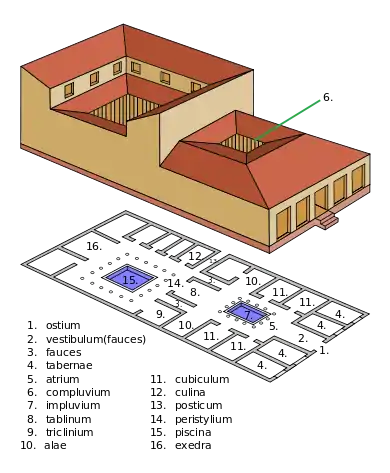

Impluvium

The impluvium is the sunken part of the atrium in a Greek or Roman house (domus). Designed to carry away the rainwater coming through the compluvium of the roof, it is usually made of marble and placed about 30 cm below the floor of the atrium and emptied into a subfloor cistern.[1]

Construction and use

Inspection (without excavation) of impluvia in Paestum, Pompeii and Rome indicated that the pavement surface in the impluvia was porous, or that the non-porous stone tiles were separated by gaps significant enough to allow a substantial quantity of water caught in the basin of the impluvium to filter through the cracks and, beyond, through layers of gravel and sand into a holding chamber below ground. A circular stone opening protected with a puteal (easily visible in one photograph, resembling a chimney pot) allows easy access by bucket and rope to this private, filtered and naturally cooled water supply.

Similar water supplies were found elsewhere in the public spaces of the city, with their stone puteals showing the wear patterns of much use (the rope wear patterns also are visible in the photograph). In wet seasons, excess water that could not pass through the filter would overflow the basin and exit the building, and any sediment or debris remaining in the surface basin could be swept away. In hot weather, water could be drawn from the cistern chamber (or fetched by slaves from supplies outside the domus) and cast into the shallow pool to evaporate and provide a cooling effect to the entire atrium: as the water evaporated, air drawn in through the compluvium was cooled and moved throughout the house to cool the surrounding living spaces, a form of passive cooling. The combination of compluvium and impluvium formed an ingenious, effective and attractive manner of collecting, filtering and cooling rainwater.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Impluvia. |

References

- John J. Dobbins and Pedar W. Foss, The World of Pompeii, Routledge Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-47577-8