Indolent lymphoma

Indolent lymphoma, also known as low-grade lymphoma, is a group of slow growing non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL).[3] Because indolent lymphoma is usually very slow growing and slow to spread, it tends to have fewer signs and symptoms when first diagnosed and may not require treatment straight away. Possible symptoms include one or more swollen but painless lymph nodes, unexplained fever and unintended weight loss.[2]

| Indolent lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Low-grade lymphoma |

| |

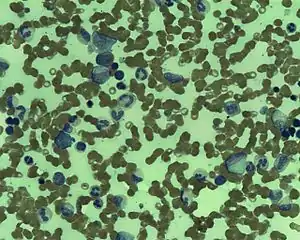

| Marrow Follicular Lymphoma | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

| Symptoms | swollen lymph nodes, chest or abdominal pain,skin lump[1] |

| Usual onset | 60s |

| Treatment | Watchful waiting, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy,[2] |

There are several subtypes of indolent lymphoma. These include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and sézary syndrome), follicular lymphoma (FL), marginal zone lymphoma, small cell lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia.[2] Follicular Lymphoma (FL) is the most common subtype.[2]

Indolent lymphoma accounts for 41 percent of all NHL cases in North America and North Europe, white people have higher incidence rates than black and Asian people.[4]The cause of the racial, ethnic and geographical disparities is poorly understood.[4] It mainly affects older adults and it affects both men and women almost equally.[5] Indolent lymphoma is considered incurable most of the time, unless the disease is localised, but due to its slow growing nature and response to effective treatment, patients often have prolonged survival.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Patients with indolent lymphoma normally present with painless, swollen lymph nodes, often in the neck, armpit or groin.[1] Sometimes patients have swollen lymph nodes inside their body, such as the chest or abdomen, which can stay undetected until they become very large and cause symptoms like cough and abdominal pain.[1]

Risk Factors

The cause of indolent lymphoma is still unknown, however research has identified a number of factors that increase the risk of developing indolent lymphoma.

Age

The risk of developing indolent lymphoma increases with age. Although the disease can occur at any age, it mainly affects older adults. It is uncommon in people under age 40 and very rare in children.

Infection

People infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at a slightly higher risk of developing indolent lymphoma than the general population.[6] For patients who were previously diagnosed with an AID-defining illness, the risk of developing indolent lymphoma is 14-fold higher.[7]

Other factors

First degree family history of NHL, hematological malignancy and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are linked to an increased risk of indolent lymphoma (iNHL).[8]There are also specific risk factors related to iNHL sub-types. Higher body mass index (BMI) as a young adult, occupation as a spray painter, sedentary lifestyle, high level of dietary animal protein intake are associated with risk of follicular lymphoma.[8][9]Residence on farm are associated with an increased risk of mantle cell lymphoma.[8] Sjögren's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, tobacco smoking for more than 40 years are linked to an increased risk of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia.

Diagnosis

Classification

Indolent lymphomas encompasses a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (NHL) that are slowly progressive.[10][11] Except for a few exceptions, indolent lymphomas are almost entirely of B cell origin.[10] They are classified based on pathological and cytological features.[10] Types of indolent lymphomas include follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, small cell lymphocytic lymhoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and hairy cell leukemia.[12]

Follicular lymphoma

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a type of B cell lymphoproliferative disorder and is generally associated with an indolent course.[13] It originates from the follicular center B cells.[13] About 85% of the cases show t(14;18)(q32;q21) chromosomal translocation, which causes the overexpression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2.[14] FL is the most prevalent form of indolent lymphoma, accounts for 70% of indolent cases and 20~30% of all NHL cases, with an incidence of 1.6 to 3.1 per 100 000 persons/year.[14][15] It is most frequently diagnosed among people in their 50s and 60s, and is more common among white populations than black or Asian populations.[16] It is characterized by diffuse lymphadenopathy, bone marrow involvement, and splenomegaly.[13] Involvement of areas outside the lymphatic sites is less common.[13] Cytopenias are relatively common but constitutional symptoms of fever, night sweats, and weight loss are uncommon in the absence of transformation to diffuse large B cell lymphoma.[13] The 5-year survival rate in the United States is 88.4%.[16]

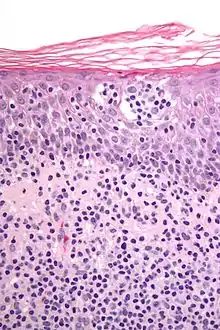

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome)

CTCL is a subtype of NHL that mainly attacks the skin, but it can also involve lymph nodes, blood and other organs. This sub-type, unlike most NHL subtypes, is derived from the T cells. Mycosis Fungoides is the most common form of CTCL, and the disease typically attacks the skin.[17] When cancer cells infiltrates into the blood and accumulates in the blood, it becomes what is called the Sézary syndrome.[17] Diagnosis of CTCL is often delayed due to the presence of multiple clinical presentations and the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria. Patients can be misdiagnosed with a variety of benign skin conditions including but not limited to dermatitis, eczema, parapsoriasis, psoriasis and adverse drug reactions.[17] It takes 6 years on average from disease onset to confirmation of diagnosis in most cases.[17]

Marginal Zone Lymphoma

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) is a heterogeneous group of indolent B cell NHL that arises from the marginal zone of lymphoid tissues.[18] It accounts for 5~10% of all NHL cases, with an annual incidence of 0.4 to 1.0 per 100,000 cases in Western countries.[19] The median age of diagnosis is 67 years, and it is slightly more common in women than in men.[20]The World Health Orgnisation categorises MZL into three distinct subtypes: nodal, extranodal and splenic.[19] Extranodal MZL occurs in areas outside the lymph nodes, with stomach being the most common site.[20]Nodal MZL occurs within the lymph nodes, and splenic MZL develops in the spleen and may spread to the blood.[18][21]

Small cell lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Small cell lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are the same disease differing in its manifestations and are managed in the same way.[22] When the abnormal lymphocytes are located mostly in the lymph nodes, it is referred to as SLL, when the abnormal lymphocytes are mostly located in the blood and bone marrow, it is called CLL.[23] CLL is the commonest leukemia in the western countries, but it is very rare East Asia, including Japan.[24]The median age at diagnosis is 72 years.[22]

Staging

Staging describes the extent of indolent lymphoma, whether it has spread, and if so how far it has spread.[2] The disease can spread through tissue, the lymphatic system and blood.[2] The Lugano modification of the Ann Arbor systems is used to stage lymphoma.[25]There are 4 stages using the Roman numerals:

Stage I Either the lymphoma is in 1 lymph nodes or 1 group of lymph nodes; or, in rare cases, in 1 organ of the lymphatic system such as the Waldeyer’s ring, thymus, or spleen; or the lymphoma is in 1 site outside the lymphatic system (IE).[2]

Stage II Either the lymphoma is in 2 or more groups of lymph nodes; or the lymphoma is in 1 nearby area outside the lymphatic system, with or without its involvement in other lymph nodes (IIE). In both cases the lymphoma sites are on the same side of the diaphragm.[2] In stage II, bulky disease means tumor mass larger than a certain size, the measurement depends on the type of lymphoma.[2]

Stage III The lymphoma is in both side of the diaphragm.[2]Either it is in lymph nodes both above and below the diaphragm, or it is in lymph nodes above the diaphragm and in the spleen.[2]

Stage IV The lymphoma is in 1 or more organs beyond the lymphatic system, such as liver, lung, bone marrow or cerebrospinal fluid.[2]

After the diagnosis of lymphoma, tests are done to determine the stage of the disease in order to predict prognosis and develop treatment plans. The following tests may be conducted in the staging process:

Imaging tests

- Chest x-rays

- CT (computed tomography) scan

- FDG-PET (fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scans

Blood tests

Bone Marrow Biopsy

Treatment

Indolent lymphoma tends to grow slowly. As a result, patients with indolent lymphoma may not need to start treatment upon diagnosis.[26] Patients are closely monitored and treatment usually starts when the disease progresses and causes symptoms.[26] This is called the "wait and watch" approach or "watchful waiting".[26] Treatment will be started if the patients have too many cancer cells in their body, even if there are no symptoms.[3]The treatment for indolent lymphoma is highly individual depending on a range of factors including the subtype of the disease, its stage, the patient's age and other medical conditions.[18]

Patients with early stage indolent lymphoma may be cured with radiation therapy alone, but most patients have widespread disease at the time of diagnosis. There are many effective treatments to control these stages of disease, but they are not reliably curative.

Treatment options for stage I and contiguous stage II adult indolent lymphoma:[2]

Radiation therapy. External radiation therapy (or external beam radiation therapy) may be given to affected lymph nodes, it may also be given to nearby lymph nodes.

Treatment options for noncontiguous stage II, III, or IV adult indolent lymphoma:[2]

Watchful waiting may be offered for patients who do not have signs or symptoms.

Rituximab monoclonal antibody therapy may be given alone, or combined with chemotherapy.

Maintenance therapy with rituximab.

Obinutuzumab monoclonal antibody therapy.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors such as copanlisib, idelalisib, or duvelisib may be used to treat relapsed indolent lymphoma.[27]

Combination immunotherapy with lenalidomide and rituximab.

Radiolabeled monoclonal antibody therapy.

Follicular lymphoma (FL)

Follicular lymphoma generally presents with an indolent course, some patients do not need treatments for several years, while others whose cancer has widely spread to lymph nodes or organs need treatment immediately.[18] In some cases, the disease can transform into an aggressive type of lymphoma, mostly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).[18]

Patients who have stage I or II FL may be closely monitored without receiving treatment, they may be treated with radiation therapy alone or with chemotherapy.[18] Patients who are in stage II but have bulky disease, in stage III/IV or have relapsed or refractory disease may be treated with therapies depending on the patient's age, overall health, disease progression, symptoms, and the patient's choice.[18] Patients may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials. Treatment options include: watchful waiting, radiation aims directly at the lymph nodes that are swollen or cause symptoms, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. For patients whose disease transforms to aggressive (high grade) NHL, autologous stem cell transplantation may be used for selected patient to improve the outcome. There is no consensus on the first line optimal treatment for follicular lymphoma, some studies find that there is no difference regarding life expectancy and quality between asymptomatic patients who receive treatments or are closely monitored. Other doctors indicate there is a under-use of radiation therapy which when appropriately used could cure a portion of the patients, and this under-use of radiation therapy may lead to excessive treatments and costs in the long term.[28]

Marginal Zone Lymphoma (MZL)

Gastric MZL is often related to Helicobacter pylori Infection, many patients can be cured with antibiotic treatment without the need of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.[18]If remission is not achieved, radiation therapy may be used. For nodal MZL that involves the spleen and blood, treatment is similar to that of follicular lymphoma.[18]

Prognosis

Although indolent lymphoma tends to progress slowly and the median overall survival is lengthy (more than 10 years), patients have a heterogenous prognosis both within and between different subtypes.[4][29]Some patients live many years longer than the estimated median survival, some die in a short period after diagnosis.[30]

Patients with HIV infection tends to have similar median survival than patients who are HIV negative.[7]

Younger patients have higher fiver year survival than older patients.[31] A study in the Netherlands shows in the younger age group, mortality caused by follicular lymphoma and Marginal zone lymphoma after 15 years is minimal, this suggest the likelihood of a cure in this age group.[31]

Epidemiology

Each year more than half a million people in the world are diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma.[32]

References

- "Low-grade NHL symptoms and diagnosis". Bloodwise. 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- "Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version". National Cancer Institute. 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- Lunning, Matthew; Vose, Julie M. (2012). "Management of Indolent Lymphoma: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going". Blood Reviews. 26 (6): 279–288. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2012.09.004. ISSN 0268-960X. PMC 3632507. PMID 23063143.

- PhD, Ines Martins (2016-02-02). "Indolent Lymphoma: What You Need to Know". Lymphoma News Today. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- Grogg, K L; Miller, R F; Dogan, A (2007). "HIV infection and lymphoma". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 60 (12): 1365–1372. doi:10.1136/jcp.2007.051953. ISSN 0021-9746. PMC 2095580. PMID 18042692.

- Levine, Alexandra M.; Sadeghi, Saeed; Espina, Byron; Tulpule, Anil; Nathwani, Bharat (2002). "Characteristics of indolent non-hodgkin lymphoma in patients with type 1 human immunodeficiency virus infection". Cancer. 94 (5): 1500–1506. doi:10.1002/cncr.10368. ISSN 1097-0142. PMID 11920507.

- Chihara, Dai; Nastoupil, Loretta J.; Williams, Jessica N.; Lee, Paul; Koff, Jean L.; Flowers, Christopher R. (2015). "New insights into the epidemiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and implications for therapy". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 15 (5): 531–544. doi:10.1586/14737140.2015.1023712. ISSN 1473-7140. PMC 4698971. PMID 25864967.

- Ambinder, Alexander J.; Shenoy, Pareen J.; Malik, Neha; Maggioncalda, Alison; Nastoupil, Loretta J.; Flowers, Christopher R. (2012). "Exploring Risk Factors for Follicular Lymphoma". Advances in Hematology. 2012: 626035. doi:10.1155/2012/626035. PMC 3458409. PMID 23028387.

- Ali W. Bseiso, M. D. (2005-04-02). "The Indolent Lymphomas". Cancer Network. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- "Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas - Hematology and Oncology". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- Zenhäusern, Reinhard (2013-03-27). "[Indolent lymphomas: classification, clinical presentation and treatment]]". Praxis. 102 (7): 399–406. doi:10.1024/1661-8157/a001239. ISSN 1661-8157. PMID 23531907.

- Freedman, Arnold; Jacobsen, Eric (2020). "Follicular lymphoma: 2020 update on diagnosis and management". American Journal of Hematology. 95 (3): 316–327. doi:10.1002/ajh.25696. ISSN 1096-8652. PMID 31814159.

- Castellino, Alessia; Vitolo, Umberto (2017-01-01). "Follicular Lymphoma: The Management of Elderly Patient". Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 9 (1): e2017009. doi:10.4084/mjhid.2017.009. ISSN 2035-3006. PMC 5224805. PMID 28105297.

- Pavanello, Francesca; Steffanoni, Sara; Ghielmini, Michele; Zucca, Emanuele (2016-11-07). "Systemic Front Line Therapy of Follicular Lymphoma: When, to Whom and How". Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 8 (1): e2016062. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2016.062. ISSN 2035-3006. PMC 5111519. PMID 27872742.

- "Follicular Lymphoma - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- Bagherani, Nooshin; Smoller, Bruce R. (2016-07-28). "An overview of cutaneous T cell lymphomas". F1000Research. 5: 1882. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8829.1. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 4965697. PMID 27540476.

- gknation (2015-02-26). "Treatment for Indolent NHL Subtypes". www.lls.org. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- Chihara, Dai; Nastoupil, Loretta J.; Williams, Jessica N.; Lee, Paul; Koff, Jean L.; Flowers, Christopher R. (2015). "New insights into the epidemiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and implications for therapy". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 15 (5): 531–544. doi:10.1586/14737140.2015.1023712. ISSN 1473-7140. PMC 4698971. PMID 25864967.

- Denlinger, Nathan M; Epperla, Narendranath; William, Basem M (2018-03-27). "Management of relapsed/refractory marginal zone lymphoma: focus on ibrutinib". Cancer Management and Research. 10: 615–624. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S133291. ISSN 1179-1322. PMC 5877869. PMID 29628774.

- "Marginal Zone Lymphoma". Lymphoma Research Foundation. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Zelenetz, Andrew D.; Gordon, Leo I.; Wierda, William G.; Abramson, Jeremy S.; Advani, Ranjana H.; Andreadis, C. Babis; Bartlett, Nancy; Byrd, John C.; Czuczman, Myron S.; Fayad, Luis E.; Fisher, Richard I. (2015). "Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 1.2015". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 13 (3): 326–362. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2015.0045. ISSN 1540-1405. PMC 4841457. PMID 25736010.

- "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- Takizawa, Jun; Gruber, Michaela; Suzuki, Ritsuro; Nakamura, Naoya; Hoermann, Gregor; Muellauer, Leonhard; Aoki, Sadao; Suzumiya, Junji; Jaeger, Ulrich (2016-12-02). "Comparative Analysis of Japanese and European Typical CLL Patients". Blood. 128 (22): 5564. doi:10.1182/blood.V128.22.5564.5564. ISSN 0006-4971.

- "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines: Classification, Diagnosis, Staging". 2019-11-11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Lymphoma - Non-Hodgkin - Subtypes". Cancer.Net. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- Mensah, Felix A; Blaize, Jean-Pierre; Bryan, Locke J (2018-08-13). "Spotlight on copanlisib and its potential in the treatment of relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: evidence to date". OncoTargets and Therapy. 11: 4817–4827. doi:10.2147/OTT.S142264. ISSN 1178-6930. PMC 6097514. PMID 30147333.

- "Many Patients With Early-Stage Follicular Lymphoma May Not Receive Guideline-Recommended Radiation Therapy - The ASCO Post". ascopost.com. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- Arcaini, Luca; Rattotti, Sara; Gotti, Manuel; Luminari, Stefano (2012-07-31). "Prognostic Assessment in Patients with Indolent B-Cell Lymphomas". The Scientific World Journal. 2012: 107892. doi:10.1100/2012/107892. ISSN 2356-6140. PMC 3417199. PMID 22919288.

- CIOBANU, Anca; STANCA, Oana; TRIANTAFYLLIDIS, Irina; LUPU, Anca (2013). "Indolent Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Prognosis in Medical Practice". Mædica. 8 (4): 338–342. ISSN 1841-9038. PMC 3968468. PMID 24790664.

- Schans, Saskia A. M. van de; Steenbergen, Liza N. van; Coebergh, Jan Willem W.; Janssen-Heijnen, Maryska L. G.; Spronsen, Dick Johan van (2014-02-01). "Actual prognosis during follow-up of survivors of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the Netherlands". Haematologica. 99 (2): 339–345. doi:10.3324/haematol.2012.081885. ISSN 0390-6078. PMC 3912965. PMID 24038025.

- "Risk factors identified for certain lymphoma subtypes". National Cancer Institute. 2014-09-02. Retrieved 2020-02-25.