Inflatable space habitat

Inflatable habitats or expandable habitats are pressurized structures capable of supporting life in outer space whose internal volume increases after launch. They have frequently been proposed for use in space applications to provide a greater volume of living space for a given mass.

The first formal design and manufacture of an inflatable space habitat was in 1961 with a space station design produced by Goodyear (although this design was never flown).[1] A proposal released in 1989 by Johnson Space Center's Man Systems Division outlined a 16 metres (52 ft) diameter spherical habitat lunar outpost which was partially buried in the lunar surface.

An inflatable module called TransHab (a portmanteau of Trans Habitation) was proposed for the International Space Station,[2] and later the private company Bigelow Aerospace revived the design for use in a number of potential civil and commercial applications.[3][4]

Construction

The construction of an inflatable space habitat is determined by its design objectives. However common elements include interwoven layers of highly durable materials such as Kevlar and mylar around a flexible air bladder which is used to retain an atmosphere. The shape of the module is maintained by the pressure difference between the internal atmosphere and the outside vacuum. The inflatable Bigelow Aerospace modules have an internal core which provides structural support during its launch into orbit.

Ongoing research

Currently the main areas of research are being undertaken by Bigelow Aerospace and NASA. NASA is currently studying inflatable lunar bases with the planetary surface habitat and airlock unit[5] which is in an early prototype phase, and has conceptual proposals for utilizing expandable-technology space structures in cislunar and interplanetary crewed exploration spacecraft.[6]

Bigelow Expandable Activity Module

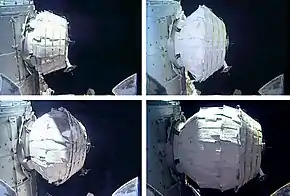

The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) is an experimental expandable space station module developed by Bigelow Aerospace, under contract to NASA, for testing as a temporary module on the International Space Station (ISS) from 2016 to at least 2020. It arrived at the ISS on April 10, 2016,[7] was berthed to the station on April 16, and was expanded and pressurized on May 28, 2016.

Bigelow Commercial Space Station

The Bigelow Next-Generation Commercial Space Station, composed of two types of expandable space habitat modules, was announced in mid-2010.[8] The initial build-out of the station was announced for 2014/2015, and would have consisted of two Sundancer modules and one B330 module.[9] Bigelow has publicly shown space station design configurations with up to nine B330 modules containing 100,000 cu ft (2,800 m3) of habitable space[10] The B330 is in final design with construction getting underway in 2011. Bigelow began to publicly refer to the initial configuration—two Sundancer modules and one B330 module—as "Space Complex Alpha" in October 2010.[11]

Bigelow announced in 2010 that it has agreements with six sovereign states to utilize on-orbit facilities of the commercial space station: United Kingdom, Netherlands, Australia, Singapore, Japan and Sweden.[10]

NASA Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle

In early 2011, NASA put forward a conceptual proposal for a long-duration crewed space transport vehicle which includes an artificial gravity space habitat intended to promote crew-health for a crew of up to six persons on missions of up to two years duration. Called the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle (MMSEV), the partial-G torus-ring centrifuge would utilize both standard metal-frame and inflatable spacecraft structures and would provide 0.11 to 0.69 G (1.0791–6.7689 m/s2 or 3.540–22.208 ft/s2).[6][12]

Related to MMSEV is the ISS Centrifuge Demo, proposed in 2011 as a demonstration project preparatory to the final design of the larger torus centrifuge space habitat for the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle. The structure would have an outside diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) with a 30 inches (760 mm) ring interior cross-section diameter and would provide 0.08 to 0.51 G (0.7848–5.0031 m/s2 or 2.575–16.414 ft/s2). This test and evaluation centrifuge would have the capability to become a sleep module for ISS crew.[6]

Advantages

- All other factors being equal, the aerodynamic load any vehicle is subjected to as it travels through an atmosphere increases with the square of its diameter. Therefore, a launch vehicle's diameter must be kept to a minimum to ensure a reasonably safe and fuel-efficient ascent through the lower atmosphere. In contrast, a vehicle designed to travel in a vacuum can be engineered without regard for aerodynamics. Because the diameter of the habitat is not strictly constrained by the diameter of the launch (and, if desired, re-entry) vehicle(s), inflatables can have a greater volume of living space for a given mass.

- Some designs offer higher resistance to space debris. For example, the B330 provides ballistic protection superior to traditional aluminum shell designs.[13]

- Some designs provide higher levels of shielding against radiation. For example, the B330 provides radiation protection equivalent to or better than the International Space Station, "and substantially reduces the dangerous impact of secondary radiation."[13]

Flight experience

As of 2019, the only designs that have flown in space have been the Genesis I, Genesis II, and Bigelow Expandable Activity Module from Bigelow Aerospace.

See also

- Planetary surface construction

- Austere Human Missions to Mars

- Colonization of the Moon

- Category:Human habitats

- Human outpost (artificially created controlled human habitat)

- Inflatable Antenna Experiment

References

- "GPN-2003-00106 - Inflatable Station Concept". Archived from the original on 2012-02-06.

- Kim Dismukes (curator) (2003-06-27). "TransHab Concept". NASA.gov. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- Holidays in space are on the horizon, New Scientist article (September 4, 2004)

- , BBC article (July 23, 2010)

- "NASA - Camping on the Moon Will Be One Far Out Experience".

- NAUTILUS - X: Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle Archived 2011-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Mark L. Holderman, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, 2011-01-26, accessed 2011-01-31.

- Pearlman, Robert (April 10, 2016). "SpaceX Dragon Arrives at Space Station, Delivers Inflatable Room Prototype". Space.com. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Bigelow Aerospace — Next-Generation Commercial Space Stations: Orbital Complex Construction Archived 2010-07-10 at the Wayback Machine, Bigelow Aerospace, accessed 2010-07-15.

- Bigelow Marketing Inflatable Space Stations, Aviation Week, 2010-05-06, accessed 2010-10-30.

- Bigelow Aerospace Shows Off Bigger, Badder Space Real Estate, Popular Mechanics, 2010-10-28, accessed 2010-10-30.

- Bigelow still thinks big, The Space Review, 2010-11-01, accessed 2010-11-02.

- NASA NAUTILUS-X: multi-mission exploration vehicle includes centrifuge, which would be tested at ISS Archived 2011-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, RLV and Space Transport News, 2011-01-28, accessed 2011-01-31.

- Bigelow Aerospace — Next-Generation Commercial Space Stations: BA 330 Archived 2010-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Bigelow Aerospace, 2010, accessed 11 Jan 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inflatable space habitat. |