Intaglio (printmaking)

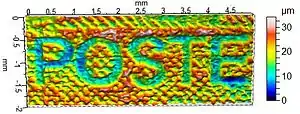

Intaglio (/ɪnˈtælioʊ/ in-TAL-ee-oh; Italian: [inˈtaʎʎo]) is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink.[1] It is the direct opposite of a relief print, where the parts of the matrix that make the image stand above the main surface.

.jpg.webp)

Normally, copper or in recent times zinc sheets, called plates, are used as a surface or matrix, and the incisions are created by etching, engraving, drypoint, aquatint or mezzotint, often in combination.[2] Collagraphs may also be printed as intaglio plates.[3]

After the decline of the main relief technique of woodcut around 1550, the intaglio techniques dominated both artistic printmaking as well as most types of illustration and popular prints until the mid 19th century.

Process

In intaglio printing, the lines to be printed are cut into a metal (e.g. copper) plate by means either of a cutting tool called a burin, held in the hand – in which case the process is called engraving; or through the corrosive action of acid – in which case the process is known as etching.[4] In etching, for example, the plate is pre-covered in a thin, acid-resistant resin or wax ground. Using etching needles or burins, the artist or writer (etcher) engraves their image (therefore to be only where the plate beneath is exposed). The plate's ground side is then dipped into acid, or the acid poured onto it. The acid bites into the surface of the plate where it was exposed. Biting is a printmaking term to describe the acid's etching, or incising, of the image; its duration depends on the acid strength, metal's reactivity, temperature, air pressure and the depth desired.[5] After the plate is sufficiently bitten it is removed from the acid bath, the ground is removed gently and the plate is usually dried or cleaned.[6]

To print an intaglio plate, ink or inks are painted, wiped and/or dabbed into the recessed lines (such as with brushes/rubber gloves/rollers). The plate is then rubbed with tarlatan cloth to remove most of its waste (surface ink) and a final smooth wipe is often done with newspaper or old public phone book pages, leaving it in the incisions. Dampened paper will usually be fed against the plate, covered by a blanket, so when pressed by rolling press it is squeezed into the plate's ink-filled grooves with uniform very high pressure.[7] The blanket is then lifted, revealing the paper and printed image. The final stages repeat for each copy needed.

Brief history

Intaglio printmaking emerged in Europe well after the woodcut print, with the earliest known surviving examples being undated designs for playing cards made in Germany, using drypoint technique, probably in the late 1430s.[8] Engraving had been used by goldsmiths to decorate metalwork, including armor, musical instruments and religious objects since ancient times, and the niello technique, which involved rubbing an alloy into the lines to give a contrasting color, also goes back to late antiquity. Scholars and practitioners of printmaking have suggested that the idea of making prints from engraved plates may well have originated with goldsmiths' practices of taking an impression on paper of a design engraved on an object, in order to keep a record of their work, or to check the quality.[9][10][8]

Martin Schongauer was one of the most significant early artists in the engraving technique, and Albrecht Dürer is one of the most famous intaglio artists. Italian and Dutch engraving began slightly after the Germans, but were well developed by 1500. Drypoint and etching were also German inventions of the fifteenth century, probably by the Housebook Master and Daniel Hopfer respectively.[11][12]

In the nineteenth century, Viennese printer Karel Klíč introduced a combined intaglio and photographic process. Photogravure retained the smooth continuous tones of photography but was printed using a chemically-etched copper plate. This permitted a photographic image to be printed on regular paper, for inclusion in books or albums.[13]

In the 1940s and 1950s the Italian security printer Gualtiero Giori brought intaglio printing into the era of high-technology by developing the first ever six-colour intaglio printing press, designed to print banknotes which combined more artistic possibilities with greater security.[14]

Current usage

At one time, intaglio printing was used for all mass-printed materials including banknotes, stock certificates, newspapers, books, maps and magazines, fabrics, wallpapers and sheet music. Today, intaglio engraving is used largely for paper or plastic currency, banknotes, passports and occasionally for high-value postage stamps. The appearance of engraving is sometimes mimicked for items such as wedding invitations by producing an embossment around lettering printed by another process (such as lithography or offset) to suggest the edges of an engraving plate.

Intaglio artists

- William Blake

- Albrecht Dürer

- M. C. Escher

- Helen Frank

- Francisco Goya

- Michael Hafftka

- Stanley William Hayter

- Edward Hopper

- William Kentridge

- Max Klinger

- Käthe Kollwitz

- Mauricio Lasansky

- Martin Lewis

- Evan K Mwendwa

- Lucas van Leyden

- Cheryl Anne Lorance

- Lothar Osterburg

- Gabor Peterdi

- Pablo Picasso

- Anton Pieck

- Krishna Reddy

- Rembrandt

- Félicien Rops

- Ludwig von Siegen

- Diane Victor

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler

References

- Strauss, Victor (1967). The printing industry: an introduction to its many branches, processes, and products. Washington: Printing Industries of America. ISBN 0835202720.

- Mustalish, Rachel (2003). "Printmaking Techniques of the WPA Printmakers". In Lisa Mintz Messinger (ed.). African American Artists, 1929–1945: Prints, Drawings and Paintings in the Metropolitan of Museum of Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Yale University Press. pp. 86–88. ISBN 0300098774.

- Mueller White, Lucy (2002). "Intaglio Processes". Printmaking as Therapy: Frameworks for Freedom. Jessica Kingsley. pp. 108–109. ISBN 1843107082.

- Ellis, Margaret Holben (1987). The Care of Prints and Drawings. Nashville: The American Association for State and Local History, 1987. p. 64.

- "Glossary – Magical-Secrets: A Printmaking Community". magical-secrets.com. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- "Intaglio Printmaking – artelino". artelino.com. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- "intaglio – printing". britannica.com. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- Harrison, Charles (2006). "The printed picture in the Renaissance." In Kim Woods (Ed.), Making Renaissance Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 219.

- Ross, John (1990). Complete Printmaker. Revised and expanded edition. New York: The Free Press. p. 65.

- Griffiths, Antony (1996). Prints and Printmaking: An introduction to the history and techniques. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 39.

- "Parshall": David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, pp5&23 ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Cohen, Brian D. "Freedom and Resistance in the Act of Engraving (or, Why Dürer Gave up on Etching)," Art in Print Vol. 7 No. 3 (September-October 2017), 18.

- "Photogravure". Notes on Photographs. George Eastman House. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- K. M. M. de Leeuw, Jan Bergstra, The History of Information Security: a Comprehensive Handbook (2007), p. 214

External links

The dictionary definition of intaglio at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of intaglio at Wiktionary Media related to Intaglio (printmaking) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Intaglio (printmaking) at Wikimedia Commons