Interior (topology)

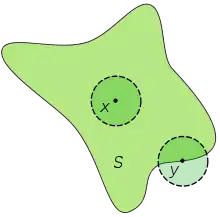

In mathematics, specifically in topology, the interior of a subset S of a topological space X is the union of all subsets of S that are open in X. A point that is in the interior of S is an interior point of S.

The interior of S is the complement of the closure of the complement of S. In this sense interior and closure are dual notions.

The exterior of a set S is the complement of the closure of S; it consists of the points that are in neither the set nor its boundary. The interior, boundary, and exterior of a subset together partition the whole space into three blocks (or fewer when one or more of these is empty). The interior and exterior are always open while the boundary is always closed. Sets with empty interior have been called boundary sets.[1]

Definitions

Interior point

If S is a subset of a Euclidean space, then x is an interior point of S if there exists an open ball centered at x which is completely contained in S. (This is illustrated in the introductory section to this article.)

This definition generalizes to any subset S of a metric space X with metric d: x is an interior point of S if there exists r > 0, such that y is in S whenever the distance d(x, y) < r.

This definition generalises to topological spaces by replacing "open ball" with "open set". Let S be a subset of a topological space X. Then x is an interior point of S if x is contained in an open subset of X which is completely contained in S. (Equivalently, x is an interior point of S if S is a neighbourhood of x.)

Interior of a set

The interior of a subset S of a topological space X, denoted by Int S or S°, can be defined in any of the following equivalent ways:

- Int S is the largest open subset of X contained (as a subset) in S

- Int S is the union of all open sets of X contained in S

- Int S is the set of all interior points of S

Examples

- In any space, the interior of the empty set is the empty set.

- In any space X, if S ⊆ X, then int S ⊆ S.

- If X is the Euclidean space ℝ of real numbers, then int([0, 1]) = (0, 1).

- If X is the Euclidean space ℝ, then the interior of the set ℚ of rational numbers is empty.

- If X is the complex plane , then

- In any Euclidean space, the interior of any finite set is the empty set.

On the set of real numbers, one can put other topologies rather than the standard one.

- If X = ℝ, where ℝ has the lower limit topology, then int([0, 1]) = [0, 1).

- If one considers on ℝ the topology in which every set is open, then int([0, 1]) = [0, 1].

- If one considers on ℝ the topology in which the only open sets are the empty set and ℝ itself, then int([0, 1]) is the empty set.

These examples show that the interior of a set depends upon the topology of the underlying space. The last two examples are special cases of the following.

- In any discrete space, since every set is open, every set is equal to its interior.

- In any indiscrete space X, since the only open sets are the empty set and X itself, we have X = int X and for every proper subset S of X, int S is the empty set.

Properties

Let X be a topological space and let S and T be subset of X.

- Int S is open in X.

- If T is open in X then T ⊆ S if and only if T ⊆ Int S.

- Int S is an open subset of S when S is given the subspace topology.

- S is an open subset of X if and only if S = int S.

- Intensive: Int S ⊆ S.

- Idempotence: Int(Int S) = Int S.

- Preserves/distributes over binary intersection: Int (S ∩ T) = (Int S) ∩ (Int T).

- Monotone/nondecreasing with respect to ⊆: If S ⊆ T then Int S ⊆ Int T.

The above statements will remain true if all instances of the symbols/words

- "interior", "Int", "open", "subset", and "largest"

are respectively replaced by

- "closure", "Cl", "closed", "superset", and "smallest"

and the following symbols are swapped:

- "⊆" swapped with "⊇"

- "∪" swapped with "∩"

For more details on this matter, see interior operator below or the article Kuratowski closure axioms.

Other properties include:

- If S is closed in X and Int T = ∅ then Int (S ∪ T) = Int S.[2]

Interior operator

The interior operator o is dual to the closure operator —, in the sense that

- ,

and also

- ,

where X is the topological space containing S, and the backslash refers to the set-theoretic difference.

Therefore, the abstract theory of closure operators and the Kuratowski closure axioms can be easily translated into the language of interior operators, by replacing sets with their complements.

In general, the interior operator does not commute with unions. However, in a complete metric space the following result does hold:

Theorem[3] (C. Ursescu) — Let X be a complete metric space and let be a sequence of subsets of X.

- If each Si is closed in X then .

- If each Si is open in X then .

Exterior of a set

The exterior of a subset S of a topological space X, denoted ext S or Ext S, is the interior int(X \ S) of its relative complement. Alternatively, it can be defined as X \ S—, the complement of the closure of S. Many properties follow in a straightforward way from those of the interior operator, such as the following.

- ext S is an open set that is disjoint with S.

- ext S is the union of all open sets that are disjoint with S.

- ext S is the largest open set that is disjoint with S.

- If S ⊆ T, then ext(S) is a superset of ext T.

Unlike the interior operator, ext is not idempotent, but the following holds:

- ext(ext S) is a superset of int S.

Interior-disjoint shapes

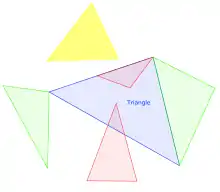

Two shapes a and b are called interior-disjoint if the intersection of their interiors is empty. Interior-disjoint shapes may or may not intersect in their boundary.

See also

References

- Kuratowski, Kazimierz (1922). "Sur l'Operation Ā de l'Analysis Situs" (PDF). Fundamenta Mathematicae. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences. 3: 182–199. ISSN 0016-2736.

- Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 371-423.

- Zalinescu, C (2002). Convex analysis in general vector spaces. River Edge, N.J. London: World Scientific. p. 33. ISBN 981-238-067-1. OCLC 285163112.

Bibliography

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989) [1966]. General Topology: Chapters 1–4 [Topologie Générale]. Éléments de mathématique. Berlin New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-64241-1. OCLC 18588129.

- Dixmier, Jacques (1984). General Topology. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Translated by Berberian, S. K. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90972-1. OCLC 10277303.

- Császár, Ákos (1978). General topology. Translated by Császár, Klára. Bristol England: Adam Hilger Ltd. ISBN 0-85274-275-4. OCLC 4146011.

- Dugundji, James (1966). Topology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-697-06889-7. OCLC 395340485.

- Joshi, K. D. (1983). Introduction to General Topology. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85226-444-7. OCLC 9218750.

- Kelley, John L. (1975). General Topology. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 27. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-90125-1. OCLC 338047.

- Munkres, James R. (2000). Topology (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 978-0-13-181629-9. OCLC 42683260.

- Narici, Lawrence; Beckenstein, Edward (2011). Topological Vector Spaces. Pure and applied mathematics (Second ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1584888666. OCLC 144216834.

- Schubert, Horst (1968). Topology. London: Macdonald & Co. ISBN 978-0-356-02077-8. OCLC 463753.

- Willard, Stephen (2004) [1970]. General Topology. Dover Books on Mathematics (First ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43479-7. OCLC 115240.