Banach space

In mathematics, more specifically in functional analysis, a Banach space (pronounced [ˈbanax]) is a complete normed vector space. Thus, a Banach space is a vector space with a metric that allows the computation of vector length and distance between vectors and is complete in the sense that a Cauchy sequence of vectors always converges to a well defined limit that is within the space.

Banach spaces are named after the Polish mathematician Stefan Banach, who introduced this concept and studied it systematically in 1920–1922 along with Hans Hahn and Eduard Helly.[1] Maurice René Fréchet was the first to use the term "Banach space" and Banach in turn then coined the term "Fréchet space."[2] Banach spaces originally grew out of the study of function spaces by Hilbert, Fréchet, and Riesz earlier in the century. Banach spaces play a central role in functional analysis. In other areas of analysis, the spaces under study are often Banach spaces.

Definition

A Banach space is a complete normed space (X, || ⋅ ||). A normed space is a pair[note 1] (X, || ⋅ ||) consisting of a vector space X over a scalar field K (where K is ℝ or ℂ) together with a distinguished[note 2] norm || ⋅ || : X → ℝ. Like all norms, this norm induces a translation invariant[note 3] distance function, called the canonical or (norm) induced metric, defined by[note 4]

- d(x, y) := ||y - x||

for all vectors x, y ∈ X. This makes X into a metric space (X, d).

A sequence x• = (xn)∞

n=1 is called d-Cauchy or Cauchy in (X, d)[note 5] or || ⋅ ||-Cauchy if and only if for every real r > 0, there exists some index N such that

- d(xn, xm) = ||xn - xm|| < r

whenever m and n are greater than N.

The canonical metric d is called a complete metric if the pair (X, d) is a complete metric space, which by definition means for every d-Cauchy sequence x• = (xn)∞

n=1 in (X, d), there exists some x ∈ X such that

where since ||xn - x|| = d(xn, x), this sequence's convergence can equivalently be expressed as:

- in (X, d).

By definition, the normed space (X, || ⋅ ||) is a Banach space if and only if (X, d) is a complete metric space, or said differently, if and only if the canonical metric d is a complete metric. The norm || ⋅ || of a normed space (X, || ⋅ ||) is called a complete norm if and only if (X, || ⋅ ||) is a Banach space.

- L-semi-inner product

For any normed space (X, || ⋅ ||), there exists an L-semi-inner product ("L" is for Günter Lumer) ⟨⋅, ⋅⟩ on X such that for all x ∈ X; in general, there may be infinitely many L-semi-inner products that satisfy this condition. L-semi-inner products are a generalization of inner products, which are what fundamentally distinguish Hilbert spaces from all other Banach spaces. This shows that all normed spaces (and hence all Banach spaces) can be considered as being generalizations of (pre-)Hilbert spaces.

- Topology

The canonical metric d of a normed space (X, || ⋅ ||) induces the usual metric topology τd on X, where this topology, which is referred to as the canonical or norm induced topology, makes (X, τd) into a Hausdorff metrizable topological space. Every normed space is automatically assumed to carry this topology, unless indicated otherwise. With this topology, every Banach space is a Baire space, although there are normed spaces that are Baire but not Banach.[3] This norm-induced topology always makes the norm into a continuous map || ⋅ || : (X, τd) → ℝ.

This norm-induced topology also makes (X, τd) into what is known as is a topological vector space (TVS),[note 6] which by definition is a vector space endowed with a topology making the operations of addition and scalar multiplication continuous. It is emphasized that the TVS (X, τd) is only a vector space together with a certain type of topology; that is to say, when considered as a TVS, it is not associated with any particular norm or metric (both of which are "forgotten").

Completeness

- Complete norms and equivalent norms

Two norms on a vector space are called equivalent if and only if they induce the same topology.[4] If p and q are two equivalent norms on a vector space X then (X, p) is a Banach space if and only if (X, q) is a Banach space. See this footnote for an example of a continuous norm on a Banach space that is not equivalent to that Banach space's given norm.[note 7][4] All norms on a finite-dimensional vector space are equivalent and every finite-dimensional normed space is a Banach space.[5]

- Complete norms vs complete metrics

Suppose that (X, || ⋅ ||) is a normed space and that τ is the norm topology induced on X. Suppose that D is any metric on X such that the topology that D induces on X is equal to τ. If D is translation invariant[note 3] then (X, || ⋅ ||) is a Banach space if and only if (X, D) is a complete metric space.[6] If D is not translation invariant, then it may be possible for (X, || ⋅ ||) to be a Banach space but (X, D) to not be a complete metric space[7] (see this footnote[note 8] for an example). In contrast, a theorem of Klee,[8][9][note 9] which also applies to all metrizable topological vector spaces, implies that if there exists any[note 10] complete metric D on X that induces the norm topology on X, then (X, || ⋅ ||) is a Banach space.

A metric D on a vector space X is induced by a norm on X if and only if D is translation invariant and absolutely homogeneous, which means that D(sx, sy) = |s| D(x, y) for all scalars s and all x, y ∈ X, in which case the function ||x|| := D(x, 0) defines a norm on X and the canonical metric induced by || ⋅ || is equal to D.

- Complete norms vs complete topological vector spaces

There is another notion of completeness besides metric completeness and that is the notion of a complete topological vector space (TVS) or TVS-completeness. This notion depends only on vector subtraction and the topology τ that the vector space is endowed with, so in particular, this notion of TVS completeness is independent of whatever norm induced the topology τ (and even applies to TVSs that are not even metrizable). Every Banach space is a complete TVS. Moreover, a normed space is a Banach space (i.e. its canonical metric is complete) if and only if it is complete as a topological vector space. Also, if (X, τ) is a topological vector space whose topology is induced by some (possibly unknown) norm, then (X, τ) is a complete topological vector space if and only if X may be assigned a norm || ⋅ || that induces on X the topology τ and also makes (X, || ⋅ ||) into a Banach space. If (X, τ) is a metrizable topological vector space (where note that every norm induced topology is metrizable), then (X, τ) is a complete TVS if and only if it is a sequentially complete TVS, meaning that it is enough to check that every Cauchy sequence in (X, τ) converges in (X, τ) to some point of X (i.e. there is no need to consider the more general notion of arbitrary Cauchy nets).

- Characterization in terms of series

The vector space structure allows one to relate the behavior of Cauchy sequences to that of converging series of vectors. A normed space X is a Banach space if and only if each absolutely convergent series in X converges in X,[10]

- .

Completions

Every normed space can be isometrically embedded onto a dense vector subspace of some Banach space, where this Banach space is called a completion of the normed space. This Hausdorff completion is unique up to isometric isomorphism.

More precisely, for every normed space X, there exist a Banach space Y and a mapping T : X → Y such that T is an isometric mapping and T(X) is dense in Y. If Z is another Banach space such that there is an isometric isomorphism from X onto a dense subset of Z, then Z is isometrically isomorphic to Y. This Banach space Y is the completion of the normed space X. The underlying metric space for Y is the same as the metric completion of X, with the vector space operations extended from X to Y. The completion of X is often denoted by .

General theory

Linear operators, isomorphisms

If X and Y are normed spaces over the same ground field K, the set of all continuous K-linear maps T : X → Y is denoted by B(X, Y). In infinite-dimensional spaces, not all linear maps are continuous. A linear mapping from a normed space X to another normed space is continuous if and only if it is bounded on the closed unit ball of X. Thus, the vector space B(X, Y) can be given the operator norm

For Y a Banach space, the space B(X, Y) is a Banach space with respect to this norm.

If X is a Banach space, the space B(X) = B(X, X) forms a unital Banach algebra; the multiplication operation is given by the composition of linear maps.

If X and Y are normed spaces, they are isomorphic normed spaces if there exists a linear bijection T : X → Y such that T and its inverse T −1 are continuous. If one of the two spaces X or Y is complete (or reflexive, separable, etc.) then so is the other space. Two normed spaces X and Y are isometrically isomorphic if in addition, T is an isometry, i.e., ||T(x)|| = ||x|| for every x in X. The Banach–Mazur distance d(X, Y) between two isomorphic but not isometric spaces X and Y gives a measure of how much the two spaces X and Y differ.

Basic notions

The cartesian product X × Y of two normed spaces is not canonically equipped with a norm. However, several equivalent norms are commonly used,[11] such as

and give rise to isomorphic normed spaces. In this sense, the product X × Y (or the direct sum X ⊕ Y) is complete if and only if the two factors are complete.

If M is a closed linear subspace of a normed space X, there is a natural norm on the quotient space X / M,

The quotient X / M is a Banach space when X is complete.[12] The quotient map from X onto X / M, sending x in X to its class x + M, is linear, onto and has norm 1, except when M = X, in which case the quotient is the null space.

The closed linear subspace M of X is said to be a complemented subspace of X if M is the range of a bounded linear projection P from X onto M. In this case, the space X is isomorphic to the direct sum of M and Ker(P), the kernel of the projection P.

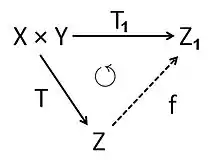

Suppose that X and Y are Banach spaces and that T ∈ B(X, Y). There exists a canonical factorization of T as[12]

where the first map π is the quotient map, and the second map T1 sends every class x + Ker(T) in the quotient to the image T(x) in Y. This is well defined because all elements in the same class have the same image. The mapping T1 is a linear bijection from X / Ker(T) onto the range T(X), whose inverse need not be bounded.

Classical spaces

Basic examples[13] of Banach spaces include: the Lp spaces and their special cases, the sequence spaces ℓp that consist of scalar sequences indexed by N; among them, the space ℓ1 of absolutely summable sequences and the space ℓ2 of square summable sequences; the space c0 of sequences tending to zero and the space ℓ∞ of bounded sequences; the space C(K) of continuous scalar functions on a compact Hausdorff space K, equipped with the max norm,

According to the Banach–Mazur theorem, every Banach space is isometrically isomorphic to a subspace of some C(K).[14] For every separable Banach space X, there is a closed subspace M of ℓ1 such that X ≅ ℓ1/M.[15]

Any Hilbert space serves as an example of a Banach space. A Hilbert space H on K = R, C is complete for a norm of the form

where

is the inner product, linear in its first argument that satisfies the following:

For example, the space L2 is a Hilbert space.

The Hardy spaces, the Sobolev spaces are examples of Banach spaces that are related to Lp spaces and have additional structure. They are important in different branches of analysis, Harmonic analysis and Partial differential equations among others.

Banach algebras

A Banach algebra is a Banach space A over K = R or C, together with a structure of algebra over K, such that the product map A × A ∋ (a, b) ↦ ab ∈ A is continuous. An equivalent norm on A can be found so that ||ab|| ≤ ||a|| ||b|| for all a, b ∈ A.

Examples

- The Banach space C(K), with the pointwise product, is a Banach algebra.

- The disk algebra A(D) consists of functions holomorphic in the open unit disk D ⊂ C and continuous on its closure: D. Equipped with the max norm on D, the disk algebra A(D) is a closed subalgebra of C(D).

- The Wiener algebra A(T) is the algebra of functions on the unit circle T with absolutely convergent Fourier series. Via the map associating a function on T to the sequence of its Fourier coefficients, this algebra is isomorphic to the Banach algebra ℓ1(Z), where the product is the convolution of sequences.

- For every Banach space X, the space B(X) of bounded linear operators on X, with the composition of maps as product, is a Banach algebra.

- A C*-algebra is a complex Banach algebra A with an antilinear involution a ↦ a∗ such that ||a∗a|| = ||a||2. The space B(H) of bounded linear operators on a Hilbert space H is a fundamental example of C*-algebra. The Gelfand–Naimark theorem states that every C*-algebra is isometrically isomorphic to a C*-subalgebra of some B(H). The space C(K) of complex continuous functions on a compact Hausdorff space K is an example of commutative C*-algebra, where the involution associates to every function f its complex conjugate f .

Dual space

If X is a normed space and K the underlying field (either the real or the complex numbers), the continuous dual space is the space of continuous linear maps from X into K, or continuous linear functionals. The notation for the continuous dual is X ′ = B(X, K) in this article.[16] Since K is a Banach space (using the absolute value as norm), the dual X ′ is a Banach space, for every normed space X.

The main tool for proving the existence of continuous linear functionals is the Hahn–Banach theorem.

- Hahn–Banach theorem. Let X be a vector space over the field K = R, C. Let further

- Y ⊆ X be a linear subspace,

- p : X → R be a sublinear function and

- f : Y → K be a linear functional so that Re( f (y)) ≤ p(y) for all y in Y.

- Then, there exists a linear functional F : X → K so that

In particular, every continuous linear functional on a subspace of a normed space can be continuously extended to the whole space, without increasing the norm of the functional.[17] An important special case is the following: for every vector x in a normed space X, there exists a continuous linear functional f on X such that

When x is not equal to the 0 vector, the functional f must have norm one, and is called a norming functional for x.

The Hahn–Banach separation theorem states that two disjoint non-empty convex sets in a real Banach space, one of them open, can be separated by a closed affine hyperplane. The open convex set lies strictly on one side of the hyperplane, the second convex set lies on the other side but may touch the hyperplane.[18]

A subset S in a Banach space X is total if the linear span of S is dense in X. The subset S is total in X if and only if the only continuous linear functional that vanishes on S is the 0 functional: this equivalence follows from the Hahn–Banach theorem.

If X is the direct sum of two closed linear subspaces M and N, then the dual X ′ of X is isomorphic to the direct sum of the duals of M and N.[19] If M is a closed linear subspace in X, one can associate the orthogonal of M in the dual,

The orthogonal M ⊥ is a closed linear subspace of the dual. The dual of M is isometrically isomorphic to X ′ / M ⊥. The dual of X / M is isometrically isomorphic to M ⊥.[20]

The dual of a separable Banach space need not be separable, but:

When X ′ is separable, the above criterion for totality can be used for proving the existence of a countable total subset in X.

Weak topologies

The weak topology on a Banach space X is the coarsest topology on X for which all elements x ′ in the continuous dual space X ′ are continuous. The norm topology is therefore finer than the weak topology. It follows from the Hahn–Banach separation theorem that the weak topology is Hausdorff, and that a norm-closed convex subset of a Banach space is also weakly closed.[22] A norm-continuous linear map between two Banach spaces X and Y is also weakly continuous, i.e., continuous from the weak topology of X to that of Y.[23]

If X is infinite-dimensional, there exist linear maps which are not continuous. The space X∗ of all linear maps from X to the underlying field K (this space X∗ is called the algebraic dual space, to distinguish it from X ′) also induces a topology on X which is finer than the weak topology, and much less used in functional analysis.

On a dual space X ′, there is a topology weaker than the weak topology of X ′, called weak* topology. It is the coarsest topology on X ′ for which all evaluation maps x′ ∈ X ′ → x′(x), x ∈ X, are continuous. Its importance comes from the Banach–Alaoglu theorem.

- Banach–Alaoglu Theorem. Let X be a normed vector space. Then the closed unit ball B ′ = {x′ ∈ X ′ : ||x′|| ≤ 1} of the dual space is compact in the weak* topology.

The Banach–Alaoglu theorem depends on Tychonoff's theorem about infinite products of compact spaces. When X is separable, the unit ball B ′ of the dual is a metrizable compact in the weak* topology.[24]

Examples of dual spaces

The dual of c0 is isometrically isomorphic to ℓ1: for every bounded linear functional f on c0, there is a unique element y = {yn} ∈ ℓ1 such that

The dual of ℓ1 is isometrically isomorphic to ℓ∞. The dual of Lp([0, 1]) is isometrically isomorphic to Lq([0, 1]) when 1 ≤ p < ∞ and 1/p + 1/q = 1.

For every vector y in a Hilbert space H, the mapping

defines a continuous linear functional fy on H. The Riesz representation theorem states that every continuous linear functional on H is of the form fy for a uniquely defined vector y in H. The mapping y ∈ H → fy is an antilinear isometric bijection from H onto its dual H ′. When the scalars are real, this map is an isometric isomorphism.

When K is a compact Hausdorff topological space, the dual M(K) of C(K) is the space of Radon measures in the sense of Bourbaki.[25] The subset P(K) of M(K) consisting of non-negative measures of mass 1 (probability measures) is a convex w*-closed subset of the unit ball of M(K). The extreme points of P(K) are the Dirac measures on K. The set of Dirac measures on K, equipped with the w*-topology, is homeomorphic to K.

- Banach–Stone Theorem. If K and L are compact Hausdorff spaces and if C(K) and C(L) are isometrically isomorphic, then the topological spaces K and L are homeomorphic.[26][27]

The result has been extended by Amir[28] and Cambern[29] to the case when the multiplicative Banach–Mazur distance between C(K) and C(L) is < 2. The theorem is no longer true when the distance is = 2.[30]

In the commutative Banach algebra C(K), the maximal ideals are precisely kernels of Dirac mesures on K,

More generally, by the Gelfand–Mazur theorem, the maximal ideals of a unital commutative Banach algebra can be identified with its characters—not merely as sets but as topological spaces: the former with the hull-kernel topology and the latter with the w*-topology. In this identification, the maximal ideal space can be viewed as a w*-compact subset of the unit ball in the dual A ′.

- Theorem. If K is a compact Hausdorff space, then the maximal ideal space Ξ of the Banach algebra C(K) is homeomorphic to K.[26]

Not every unital commutative Banach algebra is of the form C(K) for some compact Hausdorff space K. However, this statement holds if one places C(K) in the smaller category of commutative C*-algebras. Gelfand's representation theorem for commutative C*-algebras states that every commutative unital C*-algebra A is isometrically isomorphic to a C(K) space.[31] The Hausdorff compact space K here is again the maximal ideal space, also called the spectrum of A in the C*-algebra context.

Bidual

If X is a normed space, the (continuous) dual X ′′ of the dual X ′ is called bidual, or second dual of X. For every normed space X, there is a natural map,

This defines FX(x) as a continuous linear functional on X ′, i.e., an element of X ′′. The map FX : x → FX(x) is a linear map from X to X ′′. As a consequence of the existence of a norming functional f for every x in X, this map FX is isometric, thus injective.

For example, the dual of X = c0 is identified with ℓ1, and the dual of ℓ1 is identified with ℓ∞, the space of bounded scalar sequences. Under these identifications, FX is the inclusion map from c0 to ℓ∞. It is indeed isometric, but not onto.

If FX is surjective, then the normed space X is called reflexive (see below). Being the dual of a normed space, the bidual X ′′ is complete, therefore, every reflexive normed space is a Banach space.

Using the isometric embedding FX, it is customary to consider a normed space X as a subset of its bidual. When X is a Banach space, it is viewed as a closed linear subspace of X ′′. If X is not reflexive, the unit ball of X is a proper subset of the unit ball of X ′′. The Goldstine theorem states that the unit ball of a normed space is weakly*-dense in the unit ball of the bidual. In other words, for every x ′′ in the bidual, there exists a net {xj} in X so that

The net may be replaced by a weakly*-convergent sequence when the dual X ′ is separable. On the other hand, elements of the bidual of ℓ1 that are not in ℓ1 cannot be weak*-limit of sequences in ℓ1, since ℓ1 is weakly sequentially complete.

Banach's theorems

Here are the main general results about Banach spaces that go back to the time of Banach's book (Banach (1932)) and are related to the Baire category theorem. According to this theorem, a complete metric space (such as a Banach space, a Fréchet space or an F-space) cannot be equal to a union of countably many closed subsets with empty interiors. Therefore, a Banach space cannot be the union of countably many closed subspaces, unless it is already equal to one of them; a Banach space with a countable Hamel basis is finite-dimensional.

- Banach–Steinhaus Theorem. Let X be a Banach space and Y be a normed vector space. Suppose that F is a collection of continuous linear operators from X to Y. The uniform boundedness principle states that if for all x in X we have supT∈F ||T(x)||Y < ∞, then supT∈F ||T||Y < ∞.

The Banach–Steinhaus theorem is not limited to Banach spaces. It can be extended for example to the case where X is a Fréchet space, provided the conclusion is modified as follows: under the same hypothesis, there exists a neighborhood U of 0 in X such that all T in F are uniformly bounded on U,

- The Open Mapping Theorem. Let X and Y be Banach spaces and T : X → Y be a surjective continuous linear operator, then T is an open map.

- Corollary. Every one-to-one bounded linear operator from a Banach space onto a Banach space is an isomorphism.

- The First Isomorphism Theorem for Banach spaces. Suppose that X and Y are Banach spaces and that T ∈ B(X, Y). Suppose further that the range of T is closed in Y. Then X/ Ker(T) is isomorphic to T(X).

This result is a direct consequence of the preceding Banach isomorphism theorem and of the canonical factorization of bounded linear maps.

- Corollary. If a Banach space X is the internal direct sum of closed subspaces M1, ..., Mn, then X is isomorphic to M1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Mn.

This is another consequence of Banach's isomorphism theorem, applied to the continuous bijection from M1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Mn onto X sending (m1, ..., mn) to the sum m1 + ... + mn.

- The Closed Graph Theorem. Let T : X → Y be a linear mapping between Banach spaces. The graph of T is closed in X × Y if and only if T is continuous.

Reflexivity

The normed space X is called reflexive when the natural map

is surjective. Reflexive normed spaces are Banach spaces.

- Theorem. If X is a reflexive Banach space, every closed subspace of X and every quotient space of X are reflexive.

This is a consequence of the Hahn–Banach theorem. Further, by the open mapping theorem, if there is a bounded linear operator from the Banach space X onto the Banach space Y, then Y is reflexive.

- Theorem. If X is a Banach space, then X is reflexive if and only if X ′ is reflexive.

- Corollary. Let X be a reflexive Banach space. Then X is separable if and only if X ′ is separable.

Indeed, if the dual Y ′ of a Banach space Y is separable, then Y is separable. If X is reflexive and separable, then the dual of X ′ is separable, so X ′ is separable.

- Theorem. Suppose that X1, ..., Xn are normed spaces and that X = X1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Xn. Then X is reflexive if and only if each Xj is reflexive.

Hilbert spaces are reflexive. The Lp spaces are reflexive when 1 < p < ∞. More generally, uniformly convex spaces are reflexive, by the Milman–Pettis theorem. The spaces c0, ℓ1, L1([0, 1]), C([0, 1]) are not reflexive. In these examples of non-reflexive spaces X, the bidual X ′′ is "much larger" than X. Namely, under the natural isometric embedding of X into X ′′ given by the Hahn–Banach theorem, the quotient X ′′ / X is infinite-dimensional, and even nonseparable. However, Robert C. James has constructed an example[32] of a non-reflexive space, usually called "the James space" and denoted by J,[33] such that the quotient J ′′ / J is one-dimensional. Furthermore, this space J is isometrically isomorphic to its bidual.

- Theorem. A Banach space X is reflexive if and only if its unit ball is compact in the weak topology.

When X is reflexive, it follows that all closed and bounded convex subsets of X are weakly compact. In a Hilbert space H, the weak compactness of the unit ball is very often used in the following way: every bounded sequence in H has weakly convergent subsequences.

Weak compactness of the unit ball provides a tool for finding solutions in reflexive spaces to certain optimization problems. For example, every convex continuous function on the unit ball B of a reflexive space attains its minimum at some point in B.

As a special case of the preceding result, when X is a reflexive space over R, every continuous linear functional f in X ′ attains its maximum || f || on the unit ball of X. The following theorem of Robert C. James provides a converse statement.

- James' Theorem. For a Banach space the following two properties are equivalent:

- X is reflexive.

- for all f in X ′ there exists x in X with ||x|| ≤ 1, so that f (x) = || f ||.

The theorem can be extended to give a characterization of weakly compact convex sets.

On every non-reflexive Banach space X, there exist continuous linear functionals that are not norm-attaining. However, the Bishop–Phelps theorem[34] states that norm-attaining functionals are norm dense in the dual X ′ of X.

Weak convergences of sequences

A sequence {xn} in a Banach space X is weakly convergent to a vector x ∈ X if f (xn) converges to f (x) for every continuous linear functional f in the dual X ′. The sequence {xn} is a weakly Cauchy sequence if f (xn) converges to a scalar limit L( f ), for every f in X ′. A sequence { fn } in the dual X ′ is weakly* convergent to a functional f ∈ X ′ if fn (x) converges to f (x) for every x in X. Weakly Cauchy sequences, weakly convergent and weakly* convergent sequences are norm bounded, as a consequence of the Banach–Steinhaus theorem.

When the sequence {xn} in X is a weakly Cauchy sequence, the limit L above defines a bounded linear functional on the dual X ′, i.e., an element L of the bidual of X, and L is the limit of {xn} in the weak*-topology of the bidual. The Banach space X is weakly sequentially complete if every weakly Cauchy sequence is weakly convergent in X. It follows from the preceding discussion that reflexive spaces are weakly sequentially complete.

- Theorem. [35] For every measure μ, the space L1(μ) is weakly sequentially complete.

An orthonormal sequence in a Hilbert space is a simple example of a weakly convergent sequence, with limit equal to the 0 vector. The unit vector basis of ℓp, 1 < p < ∞, or of c0, is another example of a weakly null sequence, i.e., a sequence that converges weakly to 0. For every weakly null sequence in a Banach space, there exists a sequence of convex combinations of vectors from the given sequence that is norm-converging to 0.[36]

The unit vector basis of ℓ1 is not weakly Cauchy. Weakly Cauchy sequences in ℓ1 are weakly convergent, since L1-spaces are weakly sequentially complete. Actually, weakly convergent sequences in ℓ1 are norm convergent.[37] This means that ℓ1 satisfies Schur's property.

Results involving the ℓ1 basis

Weakly Cauchy sequences and the ℓ1 basis are the opposite cases of the dichotomy established in the following deep result of H. P. Rosenthal.[38]

- Theorem.[39] Let {xn} be a bounded sequence in a Banach space. Either {xn} has a weakly Cauchy subsequence, or it admits a subsequence equivalent to the standard unit vector basis of ℓ1.

A complement to this result is due to Odell and Rosenthal (1975).

- Theorem.[40] Let X be a separable Banach space. The following are equivalent:

- The space X does not contain a closed subspace isomorphic to ℓ1.

- Every element of the bidual X ′′ is the weak*-limit of a sequence {xn} in X.

By the Goldstine theorem, every element of the unit ball B ′′ of X ′′ is weak*-limit of a net in the unit ball of X. When X does not contain ℓ1, every element of B ′′ is weak*-limit of a sequence in the unit ball of X.[41]

When the Banach space X is separable, the unit ball of the dual X ′, equipped with the weak*-topology, is a metrizable compact space K,[24] and every element x ′′ in the bidual X ′′ defines a bounded function on K:

This function is continuous for the compact topology of K if and only if x ′′ is actually in X, considered as subset of X ′′. Assume in addition for the rest of the paragraph that X does not contain ℓ1. By the preceding result of Odell and Rosenthal, the function x ′′ is the pointwise limit on K of a sequence {xn} ⊂ X of continuous functions on K, it is therefore a first Baire class function on K. The unit ball of the bidual is a pointwise compact subset of the first Baire class on K.[42]

Sequences, weak and weak* compactness

When X is separable, the unit ball of the dual is weak*-compact by Banach–Alaoglu and metrizable for the weak* topology,[24] hence every bounded sequence in the dual has weakly* convergent subsequences. This applies to separable reflexive spaces, but more is true in this case, as stated below.

The weak topology of a Banach space X is metrizable if and only if X is finite-dimensional.[43] If the dual X ′ is separable, the weak topology of the unit ball of X is metrizable. This applies in particular to separable reflexive Banach spaces. Although the weak topology of the unit ball is not metrizable in general, one can characterize weak compactness using sequences.

- Eberlein–Šmulian theorem.[44] A set A in a Banach space is relatively weakly compact if and only if every sequence {an} in A has a weakly convergent subsequence.

A Banach space X is reflexive if and only if each bounded sequence in X has a weakly convergent subsequence.[45]

A weakly compact subset A in ℓ1 is norm-compact. Indeed, every sequence in A has weakly convergent subsequences by Eberlein–Šmulian, that are norm convergent by the Schur property of ℓ1.

Schauder bases

A Schauder basis in a Banach space X is a sequence {en}n ≥ 0 of vectors in X with the property that for every vector x in X, there exist uniquely defined scalars {xn}n ≥ 0 depending on x, such that

Banach spaces with a Schauder basis are necessarily separable, because the countable set of finite linear combinations with rational coefficients (say) is dense.

It follows from the Banach–Steinhaus theorem that the linear mappings {Pn} are uniformly bounded by some constant C.

Let {e∗

n} denote the coordinate functionals which assign to every x in X the coordinate xn of x in the above expansion.

They are called biorthogonal functionals. When the basis vectors have norm 1, the coordinate functionals {e∗

n} have norm ≤ 2C in the dual of X.

Most classical separable spaces have explicit bases. The Haar system {hn} is a basis for Lp([0, 1]), 1 ≤ p < ∞. The trigonometric system is a basis in Lp(T) when 1 < p < ∞. The Schauder system is a basis in the space C([0, 1]).[46] The question of whether the disk algebra A(D) has a basis[47] remained open for more than forty years, until Bočkarev showed in 1974 that A(D) admits a basis constructed from the Franklin system.[48]

Since every vector x in a Banach space X with a basis is the limit of Pn(x), with Pn of finite rank and uniformly bounded, the space X satisfies the bounded approximation property. The first example by Enflo of a space failing the approximation property was at the same time the first example of a separable Banach space without a Schauder basis.[49]

Robert C. James characterized reflexivity in Banach spaces with a basis: the space X with a Schauder basis is reflexive if and only if the basis is both shrinking and boundedly complete.[50] In this case, the biorthogonal functionals form a basis of the dual of X.

Tensor product

Let X and Y be two K-vector spaces. The tensor product X ⊗ Y of X and Y is a K-vector space Z with a bilinear mapping T : X × Y → Z which has the following universal property:

- If T1 : X × Y → Z1 is any bilinear mapping into a K-vector space Z1, then there exists a unique linear mapping f : Z → Z1 such that T1 = f ∘ T.

The image under T of a couple (x, y) in X × Y is denoted by x ⊗ y, and called a simple tensor. Every element z in X ⊗ Y is a finite sum of such simple tensors.

There are various norms that can be placed on the tensor product of the underlying vector spaces, amongst others the projective cross norm and injective cross norm introduced by A. Grothendieck in 1955.[51]

In general, the tensor product of complete spaces is not complete again. When working with Banach spaces, it is customary to say that the projective tensor product[52] of two Banach spaces X and Y is the completion of the algebraic tensor product X ⊗ Y equipped with the projective tensor norm, and similarly for the injective tensor product[53] . Grothendieck proved in particular that[54]

where K is a compact Hausdorff space, C(K, Y) the Banach space of continuous functions from K to Y and L1([0, 1], Y) the space of Bochner-measurable and integrable functions from [0, 1] to Y, and where the isomorphisms are isometric. The two isomorphisms above are the respective extensions of the map sending the tensor f ⊗ y to the vector-valued function s ∈ K → f (s)y ∈ Y.

Tensor products and the approximation property

Let X be a Banach space. The tensor product is identified isometrically with the closure in B(X) of the set of finite rank operators. When X has the approximation property, this closure coincides with the space of compact operators on X.

For every Banach space Y, there is a natural norm 1 linear map

obtained by extending the identity map of the algebraic tensor product. Grothendieck related the approximation problem to the question of whether this map is one-to-one when Y is the dual of X. Precisely, for every Banach space X, the map

is one-to-one if and only if X has the approximation property.[55]

Grothendieck conjectured that and must be different whenever X and Y are infinite-dimensional Banach spaces. This was disproved by Gilles Pisier in 1983.[56] Pisier constructed an infinite-dimensional Banach space X such that and are equal. Furthermore, just as Enflo's example, this space X is a "hand-made" space that fails to have the approximation property. On the other hand, Szankowski proved that the classical space B(ℓ2) does not have the approximation property.[57]

Some classification results

Characterizations of Hilbert space among Banach spaces

A necessary and sufficient condition for the norm of a Banach space X to be associated to an inner product is the parallelogram identity:

It follows, for example, that the Lebesgue space Lp([0, 1]) is a Hilbert space only when p = 2. If this identity is satisfied, the associated inner product is given by the polarization identity. In the case of real scalars, this gives:

For complex scalars, defining the inner product so as to be C-linear in x, antilinear in y, the polarization identity gives:

To see that the parallelogram law is sufficient, one observes in the real case that < x, y > is symmetric, and in the complex case, that it satisfies the Hermitian symmetry property and < ix, y > = i < x, y >. The parallelogram law implies that < x, y > is additive in x. It follows that it is linear over the rationals, thus linear by continuity.

Several characterizations of spaces isomorphic (rather than isometric) to Hilbert spaces are available. The parallelogram law can be extended to more than two vectors, and weakened by the introduction of a two-sided inequality with a constant c ≥ 1: Kwapień proved that if

for every integer n and all families of vectors {x1, ..., xn} ⊂ X, then the Banach space X is isomorphic to a Hilbert space.[58] Here, Ave± denotes the average over the 2n possible choices of signs ±1. In the same article, Kwapień proved that the validity of a Banach-valued Parseval's theorem for the Fourier transform characterizes Banach spaces isomorphic to Hilbert spaces.

Lindenstrauss and Tzafriri proved that a Banach space in which every closed linear subspace is complemented (that is, is the range of a bounded linear projection) is isomorphic to a Hilbert space.[59] The proof rests upon Dvoretzky's theorem about Euclidean sections of high-dimensional centrally symmetric convex bodies. In other words, Dvoretzky's theorem states that for every integer n, any finite-dimensional normed space, with dimension sufficiently large compared to n, contains subspaces nearly isometric to the n-dimensional Euclidean space.

The next result gives the solution of the so-called homogeneous space problem. An infinite-dimensional Banach space X is said to be homogeneous if it is isomorphic to all its infinite-dimensional closed subspaces. A Banach space isomorphic to ℓ2 is homogeneous, and Banach asked for the converse.[60]

- Theorem.[61] A Banach space isomorphic to all its infinite-dimensional closed subspaces is isomorphic to a separable Hilbert space.

An infinite-dimensional Banach space is hereditarily indecomposable when no subspace of it can be isomorphic to the direct sum of two infinite-dimensional Banach spaces. The Gowers dichotomy theorem[61] asserts that every infinite-dimensional Banach space X contains, either a subspace Y with unconditional basis, or a hereditarily indecomposable subspace Z, and in particular, Z is not isomorphic to its closed hyperplanes.[62] If X is homogeneous, it must therefore have an unconditional basis. It follows then from the partial solution obtained by Komorowski and Tomczak–Jaegermann, for spaces with an unconditional basis,[63] that X is isomorphic to ℓ2.

Metric classification

If is an isometry from the Banach space onto the Banach space (where both and are vector spaces over ), then the Mazur-Ulam theorem states that must be an affine transformation. In particular, if , this is maps the zero of to the zero of , then must be linear. This result implies that the metric in Banach spaces, and more generally in normed spaces, completely captures their linear structure.

Topological classification

Finite dimensional Banach spaces are homeomorphic as topological spaces, if and only if they have the same dimension as real vector spaces.

Anderson–Kadec theorem (1965–66) proves[64] that any two infinite-dimensional separable Banach spaces are homeomorphic as topological spaces. Kadec's theorem was extended by Torunczyk, who proved[65] that any two Banach spaces are homeomorphic if and only if they have the same density character, the minimum cardinality of a dense subset.

Spaces of continuous functions

When two compact Hausdorff spaces K1 and K2 are homeomorphic, the Banach spaces C(K1) and C(K2) are isometric. Conversely, when K1 is not homeomorphic to K2, the (multiplicative) Banach–Mazur distance between C(K1) and C(K2) must be greater than or equal to 2, see above the results by Amir and Cambern. Although uncountable compact metric spaces can have different homeomorphy types, one has the following result due to Milutin:[66]

- Theorem.[67] Let K be an uncountable compact metric space. Then C(K) is isomorphic to C([0, 1]).

The situation is different for countably infinite compact Hausdorff spaces. Every countably infinite compact K is homeomorphic to some closed interval of ordinal numbers

equipped with the order topology, where α is a countably infinite ordinal.[68] The Banach space C(K) is then isometric to C(<1, α >). When α, β are two countably infinite ordinals, and assuming α ≤ β, the spaces C(<1, α >) and C(<1, β >) are isomorphic if and only if β < αω.[69] For example, the Banach spaces

are mutually non-isomorphic.

Examples

A glossary of symbols:

- K = R, C;

- X is a compact Hausdorff space;

- I is a closed and bounded interval [a, b];

- p, q are real numbers with 1 < p, q < ∞ so that 1/p + 1/q = 1.

- Σ is a σ-algebra of sets;

- Ξ is an algebra of sets (for spaces only requiring finite additivity, such as the ba space);

- μ is a measure with variation |μ|.

| Classical Banach spaces | |||||

| Dual space | Reflexive | weakly sequentially complete | Norm | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kn | Kn | Yes | Yes | Euclidean space | |

| ℓn p |

ℓn q | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓn ∞ |

ℓn 1 | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓp | ℓq | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓ1 | ℓ∞ | No | Yes | ||

| ℓ∞ | ba | No | No | ||

| c | ℓ1 | No | No | ||

| c0 | ℓ1 | No | No | Isomorphic but not isometric to c. | |

| bv | ℓ∞ | No | Yes | Isometrically isomorphic to ℓ1. | |

| bv0 | ℓ∞ | No | Yes | Isometrically isomorphic to ℓ1. | |

| bs | ba | No | No | Isometrically isomorphic to ℓ∞. | |

| cs | ℓ1 | No | No | Isometrically isomorphic to c. | |

| B(X, Ξ) | ba(Ξ) | No | No | ||

| C(X) | rca(X) | No | No | ||

| ba(Ξ) | ? | No | Yes | ||

| ca(Σ) | ? | No | Yes | A closed subspace of ba(Σ). | |

| rca(Σ) | ? | No | Yes | A closed subspace of ca(Σ). | |

| Lp(μ) | Lq(μ) | Yes | Yes | ||

| L1(μ) | L∞(μ) | No | Yes | The dual is L∞(μ) if μ is σ-finite. | |

| BV(I) | ? | No | Yes | Vf (I) is the total variation of f | |

| NBV(I) | ? | No | Yes | NBV(I) consists of BV(I) functions such that | |

| AC(I) | K + L∞(I) | No | Yes | Isomorphic to the Sobolev space W 1,1(I). | |

| Cn([a, b]) | rca([a,b]) | No | No | Isomorphic to Rn ⊕ C([a,b]), essentially by Taylor's theorem. | |

Derivatives

Several concepts of a derivative may be defined on a Banach space. See the articles on the Fréchet derivative and the Gateaux derivative for details. The Fréchet derivative allows for an extension of the concept of a total derivative to Banach spaces. The Gateaux derivative allows for an extension of a directional derivative to locally convex topological vector spaces. Fréchet differentiability is a stronger condition than Gateaux differentiability. The quasi-derivative is another generalization of directional derivative that implies a stronger condition than Gateaux differentiability, but a weaker condition than Fréchet differentiability.

Generalizations

Several important spaces in functional analysis, for instance the space of all infinitely often differentiable functions R → R, or the space of all distributions on R, are complete but are not normed vector spaces and hence not Banach spaces. In Fréchet spaces one still has a complete metric, while LF-spaces are complete uniform vector spaces arising as limits of Fréchet spaces.

See also

- Space (mathematics) – Mathematical set with some added structure

- Fréchet space – A locally convex topological vector space that is also a complete metric space

- Hardy space

- Hilbert space – Mathematical generalization to infinite dimension of the notion of Euclidean space

- L-semi-inner product – Generalization of inner products that applies to all normed spaces

- Lp space – Function spaces generalizing finite-dimensional p norm spaces

- Sobolev space – Banach space of functions with norm combining Lᵖ-norms of the function and its derivatives

- Distortion problem

- Interpolation space

- Locally convex topological vector space – A vector space with a topology defined by convex open sets

- Smith space

- Topological vector space – Vector space with a notion of nearness

Notes

- It is common to read "X is a normed space" instead of the more technically correct but (usually) pedantic "(X, || ⋅ ||) is a normed space," especially if the norm is well known (e.g. such as with Lp spaces) or when there is no particular need to choose any one (equivalent) norm over any other (especially in the more abstract theory of topological vector spaces), in which case this norm (if needed) is often automatically assumed to be denoted by || ⋅ ||. However, in situations where emphasis is placed on the norm, it is common to see (X, || ⋅ ||) written instead of X. The technically correct definition of normed spaces as pairs (X, || ⋅ ||) may also become important in the context of category theory where the distinction between the categories of normed spaces, normable spaces, metric spaces, TVSs, topological spaces, etc. is usually important.

- This means that if the norm || ⋅ || is replaced with a different norm || ⋅ ||' on X, then (X, || ⋅ ||) is not the same normed space as (X, || ⋅ ||'), even if the norms are equivalent. However, equivalence of norms on a given vector space does form an equivalence relation.

- A metric D on a vector space X is said to be translation invariant if D(x, y) = D(x + z, y + z) for all vectors x, y, z ∈ X. A metric that is induced by a norm is always translation invariant.

- Because ||- z|| = ||z|| for all z ∈ X, it is always true that d(x, y) := ||y - x|| = ||x - y|| for all x, y ∈ X. So the order of x and y in this definition doesn't matter.

- Whether or not a sequence is Cauchy in (X, d) depends on the metric d and not, say, just on the topology that d induces.

- Indeed, (X, τd) is even a locally convex metrizable topological vector space

- Let (C([0, 1]), || ⋅ ||∞) denote the Banach space of continuous functions with the supremum norm and let τ∞ denote the topology on C([0, 1]) induced by || ⋅ ||∞. Since C([0, 1]) can be embedded (via the canonical inclusion) as a vector subspace of it is possible to define the restriction of the L1-norm to C([0, 1]), which will be denoted by || ⋅ ||1. This map || ⋅ ||1 : C([0, 1]) → ℝ is a norm on C([0, 1]) (in general, the restriction of any norm to any vector subspace will necessarily again be a norm). Because || ⋅ ||1 ≤ || ⋅ ||∞, the map || ⋅ ||1 : (C([0, 1]), τ∞) → ℝ is continuous. However, the norm || ⋅ ||1 is not equivalent to the norm || ⋅ ||∞. The normed space (C([0, 1]), || ⋅ ||1) is not a Banach space despite the norm || ⋅ ||1 being τ∞-continuous.

- Recall that (ℝ, |⋅|) is a Banach space where the absolute value is a norm on ℝ that induces the usual Euclidean topology on ℝ. Define a metric D : ℝ × ℝ → ℝ on ℝ by D(x, y) = |arctan (x) - arctan (y)| for all x, y ∈ ℝ. Just like |⋅| 's induced metric, the metric D also induces the usual Euclidean topology on ℝ. However, D is not a complete metric because the sequence x• = (xi)∞

i=1 defined by xi := i is a D-Cauchy sequence but it does not converge to any point of ℝ. As a consequence of not converging, this D-Cauchy sequence cannot be a Cauchy sequence in (ℝ, |⋅|) (i.e. it is not a Cauchy sequence with respect to the norm |⋅|) because if it was |⋅|-Cauchy, then the fact that (ℝ, |⋅|) is a Banach space would imply that it converges (a contradiction).Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 47–51 - The statement of the theorem is: Let d be any metric on a vector space X such that the topology 𝜏 induced by d on X makes (X, 𝜏) into a topological vector space. If (X, d) is a complete metric space then (X, 𝜏) is a complete topological vector space.

- This metric D is not assumed to be translation-invariant. So in particular, this metric D does not even have to be induced by a norm.

References

- Bourbaki 1987, V.86

- Narici & Beckenstein 2011, p. 93.

- Wilansky 2013, p. 29.

- Conrad, Keith. "Equivalence of norms" (PDF). kconrad.math.uconn.edu. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- see Corollary 1.4.18, p. 32 in Megginson (1998).

- Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 47-66.

- Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 47-51.

- Schaefer & Wolff 1999, p. 35.

- Klee, V. L. (1952). "Invariant metrics in groups (solution of a problem of Banach)" (PDF). Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 3 (3): 484–487. doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-1952-0047250-4.

- see Theorem 1.3.9, p. 20 in Megginson (1998).

- see Banach (1932), p. 182.

- see pp. 17–19 in Carothers (2005).

- see Banach (1932), pp. 11-12.

- see Banach (1932), Th. 9 p. 185.

- see Theorem 6.1, p. 55 in Carothers (2005)

- Several books about functional analysis use the notation X ∗ for the continuous dual, for example Carothers (2005), Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977), Megginson (1998), Ryan (2002), Wojtaszczyk (1991).

- Theorem 1.9.6, p. 75 in Megginson (1998)

- see also Theorem 2.2.26, p. 179 in Megginson (1998)

- see p. 19 in Carothers (2005).

- Theorems 1.10.16, 1.10.17 pp.94–95 in Megginson (1998)

- Theorem 1.12.11, p. 112 in Megginson (1998)

- Theorem 2.5.16, p. 216 in Megginson (1998).

- see II.A.8, p. 29 in Wojtaszczyk (1991)

- see Theorem 2.6.23, p. 231 in Megginson (1998).

- see N. Bourbaki, (2004), "Integration I", Springer Verlag, ISBN 3-540-41129-1.

- Eilenberg, Samuel (1942). "Banach Space Methods in Topology". Annals of Mathematics. 43 (3): 568–579. doi:10.2307/1968812. JSTOR 1968812.

- see also Banach (1932), p. 170 for metrizable K and L.

- See Amir, D. (1965). "On isomorphisms of continuous function spaces". Israel J. Math. 3 (4): 205–210. doi:10.1007/bf03008398. S2CID 122294213.

- Cambern, M. (1966). "A generalized Banach–Stone theorem". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 17 (2): 396–400. doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-1966-0196471-9. And Cambern, M. (1967). "On isomorphisms with small bound". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 18 (6): 1062–1066. doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-1967-0217580-2.

- Cohen, H. B. (1975). "A bound-two isomorphism between C(X) Banach spaces". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 50: 215–217. doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-1975-0380379-5.

- See for example Arveson, W. (1976). An Invitation to C*-Algebra. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90176-0.

- R. C. James (1951). "A non-reflexive Banach space isometric with its second conjugate space". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 37 (3): 174–177. Bibcode:1951PNAS...37..174J. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.3.174. PMC 1063327. PMID 16588998.

- see Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977), p. 25.

- bishop, See E.; Phelps, R. (1961). "A proof that every Banach space is subreflexive". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 67: 97–98. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1961-10514-4.

- see III.C.14, p. 140 in Wojtaszczyk (1991).

- see Corollary 2, p. 11 in Diestel (1984).

- see p. 85 in Diestel (1984).

- Rosenthal, Haskell P (1974). "A characterization of Banach spaces containing ℓ1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71 (6): 2411–2413. arXiv:math.FA/9210205. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.2411R. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.6.2411. PMC 388466. PMID 16592162. Rosenthal's proof is for real scalars. The complex version of the result is due to L. Dor, in Dor, Leonard E (1975). "On sequences spanning a complex ℓ1 space". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 47: 515–516. doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-1975-0358308-x.

- see p. 201 in Diestel (1984).

- Odell, Edward W.; Rosenthal, Haskell P. (1975), "A double-dual characterization of separable Banach spaces containing ℓ1" (PDF), Israel J. Math., 20 (3–4): 375–384, doi:10.1007/bf02760341, S2CID 122391702.

- Odell and Rosenthal, Sublemma p. 378 and Remark p. 379.

- for more on pointwise compact subsets of the Baire class, see Bourgain, Jean; Fremlin, D. H.; Talagrand, Michel (1978), "Pointwise Compact Sets of Baire-Measurable Functions", Am. J. Math., 100 (4): 845–886, doi:10.2307/2373913, JSTOR 2373913.

- see Proposition 2.5.14, p. 215 in Megginson (1998).

- see for example p. 49, II.C.3 in Wojtaszczyk (1991).

- see Corollary 2.8.9, p. 251 in Megginson (1998).

- see Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977) p. 3.

- the question appears p. 238, §3 in Banach's book, Banach (1932).

- see S. V. Bočkarev, "Existence of a basis in the space of functions analytic in the disc, and some properties of Franklin's system". (Russian) Mat. Sb. (N.S.) 95(137) (1974), 3–18, 159.

- see Enflo, P. (1973). "A counterexample to the approximation property in Banach spaces" (PDF). Acta Math. 130: 309–317. doi:10.1007/bf02392270. S2CID 120530273. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- see R.C. James, "Bases and reflexivity of Banach spaces". Ann. of Math. (2) 52, (1950). 518–527. See also Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977) p. 9.

- see A. Grothendieck, "Produits tensoriels topologiques et espaces nucléaires". Mem. Amer. Math. Soc. 1955 (1955), no. 16, 140 pp., and A. Grothendieck, "Résumé de la théorie métrique des produits tensoriels topologiques". Bol. Soc. Mat. São Paulo 8 1953 1–79.

- see chap. 2, p. 15 in Ryan (2002).

- see chap. 3, p. 45 in Ryan (2002).

- see Example. 2.19, p. 29, and pp. 49–50 in Ryan (2002).

- see Proposition 4.6, p. 74 in Ryan (2002).

- see Pisier, Gilles (1983), "Counterexamples to a conjecture of Grothendieck", Acta Math. 151:181–208.

- see Szankowski, Andrzej (1981), "B(H) does not have the approximation property", Acta Math. 147: 89–108. Ryan claims that this result is due to Per Enflo, p. 74 in Ryan (2002).

- see Kwapień, S. (1970), "A linear topological characterization of inner-product spaces", Studia Math. 38:277–278.

- see Lindenstrauss, J. and Tzafriri, L. (1971), "On the complemented subspaces problem", Israel J. Math. 9:263–269.

- see p. 245 in Banach (1932). The homogeneity property is called "propriété (15)" there. Banach writes: "on ne connaît aucun exemple d'espace à une infinité de dimensions qui, sans être isomorphe avec (L2), possède la propriété (15)".

- Gowers, W. T. (1996), "A new dichotomy for Banach spaces", Geom. Funct. Anal. 6:1083–1093.

- see Gowers, W. T. (1994). "A solution to Banach's hyperplane problem". Bull. London Math. Soc. 26 (6): 523–530. doi:10.1112/blms/26.6.523.

- see Komorowski, Ryszard A.; Tomczak-Jaegermann, Nicole (1995). "Banach spaces without local unconditional structure". Israel J. Math. 89 (1–3): 205–226. arXiv:math/9306211. doi:10.1007/bf02808201. S2CID 5220304. and also Komorowski, Ryszard A.; Tomczak-Jaegermann, Nicole (1998). "Erratum to: Banach spaces without local unconditional structure". Israel J. Math. 105: 85–92. arXiv:math/9607205. doi:10.1007/bf02780323. S2CID 18565676.

- C. Bessaga, A. Pełczyński (1975). Selected Topics in Infinite-Dimensional Topology. Panstwowe wyd. naukowe. pp. 177–230.

- H. Torunczyk (1981). Characterizing Hilbert Space Topology. Fundamenta MAthematicae. pp. 247–262.

- Milyutin, Alekseĭ A. (1966), "Isomorphism of the spaces of continuous functions over compact sets of the cardinality of the continuum". (Russian) Teor. Funkciĭ Funkcional. Anal. i Priložen. Vyp. 2:150–156.

- Milutin. See also Rosenthal, Haskell P., "The Banach spaces C(K)" in Handbook of the geometry of Banach spaces, Vol. 2, 1547–1602, North-Holland, Amsterdam, 2003.

- One can take α = ω βn, where β + 1 is the Cantor–Bendixson rank of K, and n > 0 is the finite number of points in the β-th derived set K(β) of K. See Mazurkiewicz, Stefan; Sierpiński, Wacław (1920), "Contribution à la topologie des ensembles dénombrables", Fundamenta Mathematicae 1: 17–27.

- Bessaga, Czesław; Pełczyński, Aleksander (1960), "Spaces of continuous functions. IV. On isomorphical classification of spaces of continuous functions", Studia Math. 19:53–62.

Bibliography

- Banach, Stefan (1932). Théorie des Opérations Linéaires [Theory of Linear Operations] (PDF). Monografie Matematyczne (in French). 1. Warszawa: Subwencji Funduszu Kultury Narodowej. Zbl 0005.20901. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Beauzamy, Bernard (1985) [1982], Introduction to Banach Spaces and their Geometry (Second revised ed.), North-Holland.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1987) [1981]. Sur certains espaces vectoriels topologiques [Topological Vector Spaces: Chapters 1–5]. Annales de l'Institut Fourier. Éléments de mathématique. 2. Translated by Eggleston, H.G.; Madan, S. Berlin New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-42338-6. OCLC 17499190.

- Carothers, Neal L. (2005), A short course on Banach space theory, London Mathematical Society Student Texts, 64, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xii+184, ISBN 0-521-84283-2.

- Conway, John (1990). A course in functional analysis. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 96 (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97245-9. OCLC 21195908.

- Diestel, Joseph (1984), Sequences and series in Banach spaces, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 92, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xii+261, ISBN 0-387-90859-5.

- Dunford, Nelson; Schwartz, Jacob T. with the assistance of W. G. Bade and R. G. Bartle (1958), Linear Operators. I. General Theory, Pure and Applied Mathematics, 7, New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc., MR 0117523

- Edwards, Robert E. (1995). Functional Analysis: Theory and Applications. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-68143-6. OCLC 30593138.

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1973). Topological Vector Spaces. Translated by Chaljub, Orlando. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. ISBN 978-0-677-30020-7. OCLC 886098.

- Jarchow, Hans (1981). Locally convex spaces. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner. ISBN 978-3-519-02224-4. OCLC 8210342.

- Khaleelulla, S. M. (1982). Counterexamples in Topological Vector Spaces. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 936. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-11565-6. OCLC 8588370.

- Köthe, Gottfried (1969). Topological Vector Spaces I. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 159. Translated by Garling, D.J.H. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-64988-2. MR 0248498. OCLC 840293704.

- Lindenstrauss, Joram; Tzafriri, Lior (1977), Classical Banach Spaces I, Sequence Spaces, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, 92, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-08072-4.

- Megginson, Robert E. (1998), An introduction to Banach space theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 183, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xx+596, ISBN 0-387-98431-3.

- Narici, Lawrence; Beckenstein, Edward (2011). Topological Vector Spaces. Pure and applied mathematics (Second ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1584888666. OCLC 144216834.

- Robertson, Alex P.; Robertson, Wendy J. (1980). Topological Vector Spaces. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics. 53. Cambridge England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29882-7. OCLC 589250.

- Rudin, Walter (1991). Functional Analysis. International Series in Pure and Applied Mathematics. 8 (Second ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math. ISBN 978-0-07-054236-5. OCLC 21163277.

- Ryan, Raymond A. (2002), Introduction to Tensor Products of Banach Spaces, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, London: Springer-Verlag, pp. xiv+225, ISBN 1-85233-437-1.

- Schaefer, Helmut H.; Wolff, Manfred P. (1999). Topological Vector Spaces. GTM. 8 (Second ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York Imprint Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-7155-0. OCLC 840278135.

- Swartz, Charles (1992). An introduction to Functional Analysis. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8643-4. OCLC 24909067.

- Trèves, François (2006) [1967]. Topological Vector Spaces, Distributions and Kernels. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-45352-1. OCLC 853623322.

- Wilansky, Albert (2013). Modern Methods in Topological Vector Spaces. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-49353-4. OCLC 849801114.

- Wojtaszczyk, Przemysław (1991), Banach spaces for analysts, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 25, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xiv+382, ISBN 0-521-35618-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banach spaces. |

- "Banach space", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Banach Space". MathWorld.