Investment-specific technological progress

Investment-specific technological progress refers to progress that requires investment in new equipment and structures embodying the latest technology in order to realize its benefits. To model the influence of technological change upon production the influence of a technological change upon the specific inputs (i.e. labor and capital) of a production model is assessed in terms of the resulting effect upon the final good of the model (i.e. goods and services).

To realize the benefits of such technological change for production a firm must invest to attain the new technology as a component of production. For example, the advent of the microchip (an important technological improvement in computers) will affect the production of Ford cars only if Ford Motor Co.'s assembly plants invest in computers with microchips (instead of computers with punched cards) and use them in the production of a product, i.e. Mustangs. Investment-specific technological progress requires investing in new production inputs which contain or embody the latest technology. Notice that the term investment can be general: not only must a firm buy the new technology to reap its benefits, but it also must invest in training its workers and managers to be able to use this new technology.[1]

Significance

Identifying investment-specific technological progress within an economy will determine how an individual behaves in reaction to new technology, i.e. whether the individual will invest their savings.[2] If "investment-specific" technological change is the main source of progress in an industry, then the individual would invest in firms to purchase and develop new capital, as technological improvements result in improvements to the goods available to consume. Firms may also choose to train current employees in the new technology or subsidize the education of new employees in the operation of the new technology. As such technological progress has an impact upon the labour market.[3]

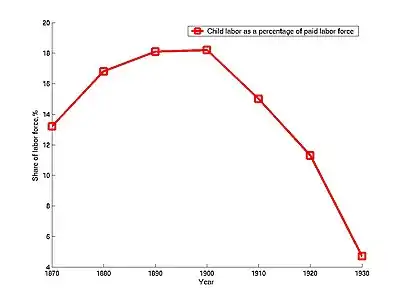

Technological progress has direct positive impacts upon human welfare. As a result of new technologies producers can produce a greater volume of product at a lower cost. The resulting reduction in prices benefits the consumer, who now can purchase more.[4] Women have been able to break away from the traditional "housewife" role, join the labor-force in greater numbers and become less economically dependent on men.[5] Further impacts include a reduction in child labor starting around 1900.[6]

An example of investment-specific technological progress is the microwave oven. The first microwave oven cost between $2000 and $3000 US and was housed in refrigerator-sized cabinets. Through regular technological investment the microwave industry has developed into a competitive market, with small compact units in many households.[7] Many industries have adopted the microwave through capital or research investment, applications outside the food industry include the iron and steel industry as a heating tool[8] and the chemical industry as a tool for organic synthesis.[9]

Measurement

There is no direct metric for measuring technological progress, as such workarounds based upon direct relationships between technological progress and recordable values are used. "'Investment-specific'" technological progress makes producing goods easier, as a result the price of the goods will decrease. In particular, "investment-specific" technological advance has affected the prices of two inputs into the production process: equipment and structures. If there is technological progress in the production of these goods, then it is expected the price will fall or the value of the good will rise relative to older versions of the same good.

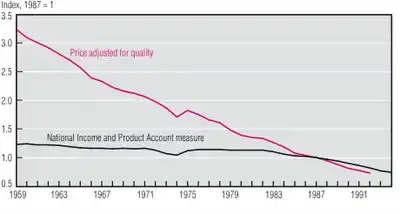

Figure 2 (the pink line) shows how the price of new producer durables (such as equipment) in the United States relative to the price of new consumer nondurables has consistently declined over the past fifty years.[10] To calculate the relative price of producer durables divide the price that firms pay (for the durable inputs of production) by the price that a consumer of the firms product pays. Relative prices are used to represent how many units of equipment can be bought in terms of the a single unit of consumer goods.As a result of technological development, firms have been able to buy comparitevly more units of equipment for each unit of consumption, with the quality of the goods increasing while the cost of production decreases. When changes in quality are not taken into account the apparent price of equipment undergoes a smaller reduction (see the black line in Figure 2).

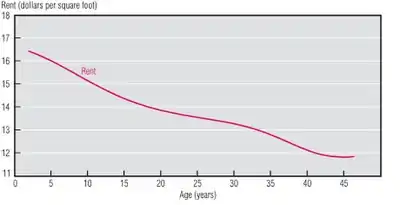

One approach to measuring the price of technologicaly improved structures is to assign newer building a higher value due to the embodyment of the new technology with the design.[11] In particular, they should rent for more, i.e. renting a square foot in a new building is much more expensive than renting a square foot in a building forty years old.

Figures 2 and 3 suggest that investment-specific technological change is operating in the US. The annual rate of technological progress in equipment and structures has been estimated to be about 3.2% and 1%, respectively.[12]

References

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Jovanovic, Boyan (2001). New developments in productivity analysis - Accounting for Growth. Hulten, Charles R., Dean, Edwin., Harper, Michael J., Conference on Research in Income and Wealth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-36064-4. OCLC 290503961.

- Gort, Michael; Greenwood, Jeremy; Rupert, Peter (March 1, 1999). "How Much of Economic Growth is Fueled by Investment-Specific Technological Change?". Economic Commentary. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland: 1.

- Krusell, Per (1998), "Investment-Specific R and D and the Decline in the Relative Price of Capital", Journal of Economic Growth, 3 (2): 131–141, doi:10.1023/a:1009701518509, S2CID 154164754

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Vandenbroucke, Guillaume (2006), "Hours Worked: Long-Run Trends", in Lawrence E. Blume, Steven N. Durlauf (ed.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.), London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Guner, Nezih (2009), "Marriage and Divorce since World War II: Analyzing the Role of Technological Progress on the Formation of Households" (PDF), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2008, 23: 231–276, doi:10.1086/593087, S2CID 4713240

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth (2005), "Technological Progress and Economic Transformation", in Philippe Aghion and Steven N. Durlauf (ed.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Gallawa, J. Carlton (2005), Who Invented Microwaves

- Yoshikawa, Noboru; Ishizuka, Etsuko; Mashiko, Kenichi; Chen, Yan; Taniguchi, Shoji (2007). "Brief Review on Microwave (MW) Heating, Its Application to Iron & Steel Industry and to the Relevant Environmental Techniques". ISIJ International. 47 (4): 523–527. doi:10.2355/isijinternational.47.523. ISSN 0915-1559.

- Milestones in microwave chemistry. Keglevich, György. Switzerland. 22 March 2016. ISBN 978-3-319-30632-2. OCLC 945552571.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gort, Michael; Greenwood, Jeremy; Rupert, Peter (March 1, 1999), "How Much of Economic Growth is Fueled by Investment-Specific Technological Change?", Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- Gort, Michael; Greenwood, Jeremy; Rupert, Peter (March 1, 1999), "How Much of Economic Growth is Fueled by Investment-Specific Technological Change?", Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Hercowitz, Zvi; Krusell, Per (1997), "Long-Run Implications of Investment-Specific Technological Change", American Economic Review, 87 (3): 342–362