Irish Language Act

The Irish Language Act (Irish: Acht na Gaeilge) is proposed legislation in Northern Ireland that would give the Irish language equal status to English in the region, similar to that of the Welsh language in Wales under the Welsh Language Act 1993.[1] It is supported by the Republic of Ireland,[2] Sinn Féin, SDLP, the Alliance Party,[1] and the Green Party,[3] and opposed by the Democratic Unionist Party and Ulster Unionist Party.[4]

Sinn Féin[5] and POBAL, the Northern Irish association of Irish speakers, say that the act was promised to them in the 2006 St Andrews Agreement.[1] Unionists say that prior commitments have already been honoured.[3] As part of the New Decade, New Approach compromise agreement, many of the proposals sought under an Irish Language Act were implemented by amending existing laws rather than introducing a new standalone law.[6]

Background

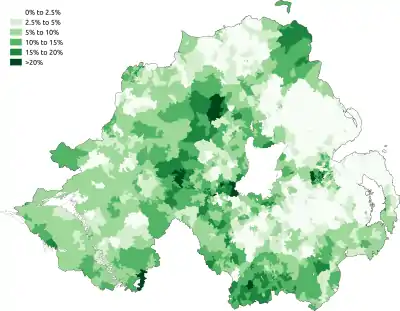

About 184,898 (10.65%) Northern Irish people claim some knowledge of Irish, while about 4,130 (0.2%) speak it as their vernacular.[7]

Currently, the status of the Irish language is guaranteed by the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, which will continue to bind the United Kingdom after Brexit.[8] Since 2008, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin has been advocating that these protections be strengthened by legislation.[9]

Potential contents

According to TheJournal.ie, the legislation sought by Sinn Féin would also appoint an Irish language commissioner and designate Gaeltacht areas. It would also provide for the right to use Irish:[1]

- In the judicial system

- In the Northern Ireland Assembly (Stormont)

- With public sector services

- In Irish-medium education

- On bilingual signage

Conradh na Gaeilge (an all-island non-political social and cultural organisation which promotes the language in Ireland and worldwide) proposes[10] an Act that would provide for

- the Official status of the language;

- Irish in the Assembly;

- Irish in Local Government;

- Irish and the BBC;

- Irish in the Department of Education;

- the role of a Language Commissioner; and

- placenames.

Other proposals have included replicating the Welsh or the Scottish Act.

Support and opposition

Irish language activist and unionist Linda Ervine stated that she had come to support the legislation after comments by Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) MLA Gregory Campbell mocking the Irish language.[11] She said that the act would have little effect on non-Irish speakers and that some politicians had engaged in "scaremongering". When a draft bill was leaked after talks stalled in 2018, Irish language groups criticized the legislation for not going far enough, specifically in not creating new rights for Irish speakers.[2] Meanwhile, DUP supporters condemned the compromise legislation.[12]

In 2017, pressure group An Dream Dearg organized a rally in favour of the act in Belfast, attracting several thousand supporters.[13] In May 2019, more than 200 prominent Irish people signed an open letter urging Republic of Ireland head of government Leo Varadkar and then-Prime Minister of the UK Theresa May to support the act.[14]

DUP leader Arlene Foster has stated that it would make more sense to pass a Polish Language Act than an Irish Language Act, because more Northern Ireland residents speak Polish than Irish. Her claim has been disputed by fact checkers. Foster also stated that "If you feed a crocodile they're going to keep coming back and looking for more" with regard to Sinn Féin's demands for the act and accused the party of "using the Irish language as a tool to beat Unionism over the head."[15][16]

Role in political deadlock (2017–2020)

In January 2017, Sinn Féin deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness resigned in protest over the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal,[17] and the party declined to replace him.[18] Due to Northern Ireland's power-sharing system, a government cannot be formed without both parties,[19] and the Stormont Assembly was suspended.[20]

Gerry Adams, then Sinn Féin leader, stated in August 2017 that "There won't be an assembly without an Acht na Gaeilge."[3] According to The Independent in 2019, the Irish Language Act has become the most public issue of disagreement in discussions about restoring Stormont, and it is "almost certainly" required for a deal to be made to end the deadlock.[12]

Compromise (2020)

On 11 January 2020, Sinn Féin and the DUP re-entered devolved government under the New Decade, New Approach agreement with DUP leader Arlene Foster appointed Northern Ireland's first minister, and Sinn Féin's Michelle O'Neill appointed deputy first minister.[21] As part of the agreement, there will be no standalone Irish Language Act, but the Northern Ireland Act 1998 will be amended and policies implemented to:

- grant official status to both the Irish language and Ulster Scots in Northern Ireland;[22]

- establish the post of Irish Language Commissioner to "recognise, support, protect and enhance the development of the Irish language in Northern Ireland" as part of a new Office of Identity and Cultural Expression (alongside an Ulster Scots/Ulster British Commissioner);[6]

- introduce sliding-scale "language standards", a similar approach to that taken for the Welsh language in Wales, although they are subject to veto by the First Minister or deputy First Minister;[23]

- repeal a 1737 ban on the use of Irish in Northern Ireland's courts;[6]

- allow members of the Northern Ireland Assembly to speak in Irish or Ulster Scots, with simultaneous translation for non-speakers,[24] and

- establish a central translation unit within the Northern Ireland government.[24]

References

- Burke, Ceimin (14 February 2018). "Explainer: What is the Irish Language Act and why is it causing political deadlock in Northern Ireland?". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Manley, John (22 February 2018). "Irish act in draft agreement did not go far enough, groups say". Irish News. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Adams: 'No assembly without language act'". BBC. 30 August 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Meredith, Robbie (15 March 2019). "Language laws 'strengthen not threaten'". BBC. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- McCorley, Rosie. "95% of people support Acht na Gaeilge". Sinn Féin. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Meredith, Robbie (10 January 2020). "NI experts examine the detail of deal: Language". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "The role of the Irish language in Northern Ireland's deadlock". The Economist. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Sonnad, Nikhil. "Brexit may threaten the many minority languages of Britain". Quartz. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Sinn Féin launches two new Irish language cumainn". An Phoblacht. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Irish-Language Act". Conradh na Gaeilge. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Linda Ervine: 'Curry my yoghurt' pushed me towards Irish act". Belfast News Letter. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Kelly, Ben (30 April 2019). "Why is there no government in Northern Ireland?". The Independent. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Ferguson, Amanda (20 May 2017). "Thousands call for Irish Language Act during Belfast rally". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Moriarty, Gerry; Caollaí, Éanna Ó. "Varadkar and May urged to implement Irish language act in North". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- MacGuill, Dan. "FactCheck: Are there really more Polish speakers than Irish speakers in Northern Ireland?". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Arlene Foster regrets Sinn Féin 'crocodiles' comment". The Irish Times. 9 March 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Henry McDonald (10 January 2017). "Martin McGuinness resigns as deputy first minister of Northern Ireland". The Guardian. London, England. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- McDonald, Henry; Walker, Peter (16 January 2017). "Sinn Féin refusal to replace McGuinness set to trigger Northern Ireland elections". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Power-sharing". Northern Ireland Assembly Education Service. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Bradfield, Philip (22 September 2018). "Linda Ervine: Stormont should not have stopped for Irish Act". News Letter. Belfast, Northern Ireland. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Stormont deal: Arlene Foster and Michelle O'Neill new top NI ministers". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- "What's in the draft Stormont deal?". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 10 January 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Walsh, Dr John (15 January 2020). "What's the real deal with Stormont's Irish language proposals?". RTE. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Hughes, Brendan (11 January 2020). "How the Stormont deal tackles language and identity issues". The Irish News. Retrieved 26 June 2020.