Italian Army in Russia

The Italian Army in Russia (Italian: Armata Italiana in Russia; ARMIR) was an army-sized unit of the Royal Italian Army which fought on the Eastern Front during World War II. The ARMIR was also known as the 8th Italian Army and initially had 235,000 soldiers.

Formation

In July 1942, the ARMIR was created when Italian dictator Benito Mussolini decided to scale up the Italian effort in the Soviet Union. The existing Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia, or CSIR) was expanded to become the ARMIR. Unlike the "mobile" CSIR which it replaced, the ARMIR was primarily an infantry army. A good portion of the ARMIR was made up of mountain troops (Alpini). While in many ways the mountain troops added greatly to the capabilities of the ARMIR, in other ways these elite mountain fighters were ill-suited to the vast, flat expanses of southern Russia.

Like the CSIR, the ARMIR included an Aviation Command (Comando Aereo) with a limited number of fighters, bombers, and transport aircraft. This command was part of the Regia Aeronautica (lit. "Royal Air Force") and was also known as the Corpo Aereo Spedizione in Russia ("Air Expeditionary Corps in Russia"). The ARMIR was subordinated to German Army Group B (Heeresgruppe B) commanded by General Maximilian von Weichs. In February 1943, after its near destruction during the Battle of Stalingrad, Mussolini disbanded what was left of the Italian 8th Army and the surviving Italian troops were unceremoniously brought home from Russia.

Composition

Mussolini sent seven new divisions to Russia for a total of ten divisions. Four new infantry divisions were sent: the 2 Infantry Division Sforzesca, the 3 Infantry Division Ravenna, the 5 Infantry Division Cosseria, and the 156 Infantry Division Vicenza. In addition to the infantry divisions, three new mountain divisions made up of Alpini were sent: the 2 Alpine Division Tridentina, the 3 Alpine Division Julia, and the 4 Alpine Division Cuneense. These new divisions were added to the 52 Motorised Division Torino, 9 Motorised Division Pasubio and 3 Cavalry Division Amedeo Duca d'Aosta which were already in Russia as part of the CSIR.[1]

The 8th Italian Army was organized into three corps: The XXXV Army Corps, the II Army Corps, and the Mountain (Alpini) Corps. The XXXV Corps included the three divisions of the CSIR: Torino, Pasubio, and Amedeo Duca d'Aosta. The II Corps included the new Sforzesca, Ravenna, and Cosseria divisions. The Mountain Corps included the Tridentina, the Julia, and Cuneense divisions. The Vicenza Division was under direct command of the 8th Army and was primarily utilized behind the front on "lines of communications" duties, security and anti-partisan and to act as a reserve. In addition to the ten divisions, the 8th Italian Army included the 298th and 62nd German divisions (the latter being sent to Stalingrad), a Croatian volunteer legion, and three legions of Italian Blackshirt volunteers (Camicie Nere, or CCNN).

By November 1942, the 8th Italian Army had a total of 235,000 men in twelve divisions and four legions. It was equipped with 988 guns, 420 mortars, 25,000 horses, and 17,000 vehicles. While the Italians did receive 12 German Mk. IV tanks and had captured several Soviet tanks, there were still very few modern tanks and anti-tank guns available to the ARMIR. The few tanks that were available still tended to be obsolete Italian models. Both the L6/40 light tanks (armed with a turret-mounted 20 mm Breda Model 35 gun) and the 47 mm anti-tank guns (Cannone da 47/32 M35) were out of date when Italy declared war on 10 June 1940. Compared to what the Soviets had available to them in late 1942 and early 1943, Italian tanks and anti-tank guns could be considered more dangerous to the crews than to the enemy. Moreover, as was the complaint of General Messe with the CSIR, the ARMIR was seriously short of adequate winter equipment. Infantry small arms were also often inadequate or even useless. Rifles and machine guns were terribly prone to jamming. The Carcano rifle and the Breda 30 light machine gun had to be kept for a long time on a source of heat to work properly in extreme climatic conditions, and thus were often not capable of firing in the midst of battle. Incidentally, these last two weapons were considered the deadliest among the Italian arsenal. The heavy Breda M37 proved to be a slightly more reliable machine gun, though having an excessive weight and very slow rate of fire. The old belt-fed Fiat 14 was also seen in small numbers, but was obsolete. The praised high-quality Beretta 38A submachine guns were extremely rare, and given only in small numbers to specialized units, such as the Blackshirt legions, some tank crews or Carabinieri military police. Italian paratroopers in North Africa were equipped exclusively with this weapon, and gave outstanding combat results. There was total absence of any portable anti-tank weapon, thus making hand grenades, machine guns and mortars the last resort against Soviet armour. Hand grenades rarely detonated or detonated unpredictably. The Brixia Model 35 45mm mortar bombs had an inadequate explosive charge and fragmented poorly, and larger 81mm mortars modello 35 were rare.

The Aviation Command of the ARMIR had a total of roughly 64 aircraft. The ARMIR had the following aircraft available to it: Macchi C.200 “Thunder" (Saetta) fighter, Macchi C.202 “Lightning" (Folgore) fighter, Caproni Ca.311 light reconnaissance-bomber, and Fiat Br.20 “Stork" (Cicogna) twin-engined bomber.

Commander

Italian General Italo Gariboldi took command of the newly formed ARMIR from General Giovanni Messe. As commander of the CSIR, Messe had opposed an enlargement of the Italian contingent in Russia until it could be properly equipped. As a result, he was dismissed by Mussolini and the CSIR was expanded without his further input. Just prior to commanding the ARMIR, Gariboldi was the Governor-General of Italian Libya. He was criticized after the war for being too submissive to the Germans in North Africa.

Main operations

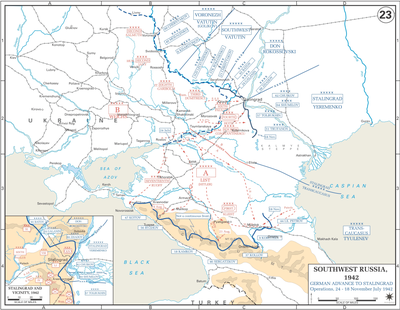

In late summer 1942, after participating in the conquest of eastern Ukraine, the highly-mobile riflemen (Bersaglieri) of the ARMIR eliminated the Soviet bridgehead at Serafimovič on the Don river. Then, with the support of German tanks, the Gariboldi troops repelled a Soviet attack during the first defensive battle of the Don.[2]

Finally the ARMIR faced Operation Little Saturn in December 1942. The aim of this Soviet operation was the complete annihilation of the Italian 8th Army, as a result of the operations related to the Battle of Stalingrad.

On 11 December 1942 the Soviet 63rd Army, backed by T-34 tanks and fighter-bombers, first attacked the weakest Italian sector. This sector was held on the right by the Ravenna and Cosseria infantry divisions. Indeed, from the Soviet bridgehead at Mamon, 15 divisions—supported by at least 100 tanks—attacked the Italian Cosseria and Ravenna Divisions, and although outnumbered 9 to 1, the Italians resisted until 19 December, when ARMIR headquarters finally ordered the battered divisions to withdraw.[3] Only before Christmas both divisions were driven back and defeated, after heavy and bloody fighting.

Meanwhile, on 17 December 1942, the Soviet 21st Army and the Soviet 5th Tank Army attacked and defeated what remained of the Romanians to the right of the Italians. At about the same time, the Soviet 3rd Tank Army and parts of the Soviet 40th Army hit the Hungarians to the left of the Italians. This resulted in a collapse of the Axis front, north of Stalingrad: the ARMIR was encircled, but for some days the Italian troops were able—with huge casualties—to stop the attacking Soviet troops.

The Soviet 1st Guards Army then attacked the Italian center which was held by the 298th German, the Pasubio, the Torino, the Prince Amedeo Duke of Aosta, and the Sforzesca divisions. After eleven days of bloody fighting against overwhelming Soviet forces, these divisions were surrounded and defeated and Russian air support resulted in the death of General Paolo Tarnassi, commander of the Italian armoured force in Russia.[4]

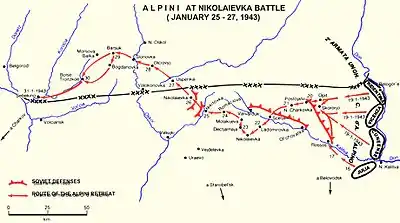

On 14 January 1943, after a short pause, the 6th Soviet Army attacked the Alpini divisions of the Italian Mountain Corps. These units had been placed on the left flank of the Italian army and, to date, were still relatively unaffected by the battle. However, the Alpini’s position had turned critical after the collapse of the Italian center, the collapse of the Italian right flank, and the simultaneous collapse of the Hungarian troops to the left of the Alpini. The Julia Division and Cuneense Division were destroyed. Members of the 1 Alpini Regiment, part of Cuneese Division, burned the regimental flags to keep them from being captured. Part of the Tridentina Division and other withdrawing troops managed to escape the encirclement.

On 26 January 1943, the Alpini remnants breached the encirclement and reached new defensive positions set up to the west by the German Army. Many of the troops who managed to escape were frostbitten, critically ill, and deeply demoralized: for practical purposes, the Italian Army in Russia did not exist anymore by February 1943.

"The Italian participation in operations in Russia proved extremely costly. Losses of the 8th Army from 20 August 1942-20 February 1943 totaled 87,795 killed and missing (3,168 officers and 84,627 NCOs and soldiers) and 34,474 wounded and frostbitten (1,527 officers and 32,947 NCOs and soldiers). In March–April 1943, the remnants of the Army returned to Italy for rest and reorganization. Upon the surrender of Italy in September 1943, the Army was disbanded."[5]

Officially, ARMIR losses were 114,520 of the original 235,000 soldiers [6]

See also

- "Italiani brava gente", a term coined to refer to Italian historical memory of the Second World War

- Charge of the Savoia Cavalleria at Isbuscenskij

- Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito)

- Italian participation in the Eastern Front

- Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Military equipment of Axis Power forces in Balkans and Russian Front

- Light Transport Brigade (Croatian: Laki prijevozni zdrug, Italian: Legione Croata Autotransportabile)

Armies with the Italian 8th Army and Army Group B at Stalingrad:

References

- Jowett, p. 11

- Italian Ministry of Defence, 1977a. Valori, 1951

- Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International. p. 177. ISBN 0-275-98505-9. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Italian General Reported Killed, New York Times, 15 January 1943

- ARMIR losses, according to Shawn Bohannon

- Alfio Caruso. Tutti i vivi all'assalto, Longanesi, 2003, ISBN 978-88-502-0912-5

Sources

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000). Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 – Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtsteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Jowett, Philip S. The Italian Army 1940–45 (1): Europe 1940–1943. Osprey, Oxford – New York, 2000. ISBN 978-1-85532-864-8

- Mollo, Andrew (1981). The Armed Forces of World War II. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-54478-4.

Further reading

- Hamilton, H. Sacrifice on the Steppe. Casemate, 2011 (English)