Italian irredentism in Dalmatia

Italian irredentism in Dalmatia was the political movement supporting the unification to Italy, during the 19th and 20th centuries, of adriatic Dalmatia.

History

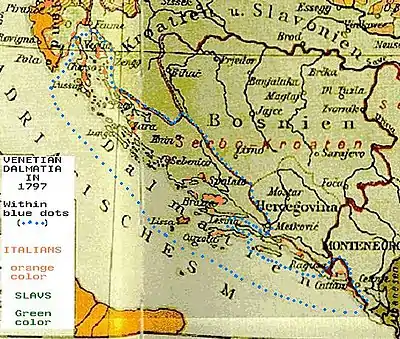

The Italian linguist Matteo Bartoli calculated that Italian was the primary spoken language by almost 30% of the Dalmatian population at the beginning of the Napoleonic wars.[1] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims: Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1814–1815 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 25% of the total population of Dalmatia. Accordingly, three years later an Austrian census found around 70,000 Italians in a total of 301,000 people living in Austrian Dalmatia.[2]

With the development of Croatian nationalism, critics such as Croatian historian Duško Večerina alleged that these evaluations were not conducted by modern scientific standards and that they took spoken language as the criterion, rather than blood, origin and ethnicity. They pointed out that according to a report by Imperial court councillor Joseph Fölch in 1827, the Italian language was spoken by noblemen and some citizens of middle and lower classes exclusively in the coastal cities of Zadar, Šibenik and Split. Since only around 20,000 people populated these towns and not all were Italian speakers, they claim that the real number was rather smaller, probably around 7% of the total population, as is asserted by the Department of Historical Studies of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (HAZU).[3]

Another evidence about the Dalmatian population comes from the 1857 Austro-Hungarian census, which showed that in this year there were 369,310 indigenous Croatians and 45,000 Italians in Dalmatia,[4] making Dalmatian Italians 10.8% of the total population of Dalmatia in the mid-19th century.

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy joined the Triple Entente Allies in 1915 upon agreeing to the London Pact that guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Vis, Lastovo, Šibenik, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[5] By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the London Pact and by 17 November had seized Fiume as well.[6] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[6] Famous Italian nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia, and proceeded to occupy some areas in an Italian warship in December 1918.[7]

The last city with a significant Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara (now called Zadar). In the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910 the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69.3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). The population grew to 24,100 inhabitants, of which 20,300 Italians, when was in 1942 the capital of the Governorate of Dalmatia (the "Governorate" fulfilled the aspirations of the Italian irredentism in the Adriatic).

In 1943, Josip Broz Tito informed the Allies that Zara was a chief logistic centre for German forces in Yugoslavia. By overstating its importance, he persuaded them of its military significance. Italy surrendered in September 1943 and over the following year, specifically between 2 November 1943 and 31 October 1944, Allied Forces bombarded the town fifty-four times.

Nearly 2,000 people were buried beneath rubble; 10–12,000 people escaped and took refuge in Trieste and slightly over 1,000 reached Apulia.

Tito's partisans entered in the city on 31 October 1944, and 138 people were killed.[8] With the Peace Treaty of 1947, Italians still living in the city and in Dalmatia followed the Italian exodus from Istria and Dalmatia and only about 100 Dalmatian Italians now remain in actual Zadar.

Notes

- Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. p.46

- Italian irredentism in Dalmatia

- O broju Talijana/Talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. Stoljeća”, Zavod za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru, 2002, UDK 949.75:329.7”19”Dalmacija 2002, p. 344

(“Concerning the number of Italians/pro-Italians in Dalmatia in the 19th century”) See http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=18696 - Statistisches Handbüchlein für die Oesterreichische Monarchie Page 38 - Von Direction der Administrativen Statistik, Österreich - Veröffentlicht 1861

- Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- A. Rossi. The Rise of Italian Fascism: 1918-1922. New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2010. Pp. 47.

- Lovrovici, don Giovanni Eleuterio. Zara dai bombardamenti all'esodo (1943-1947) Tipografia Santa Lucia - Marino. Roma, 1974. pag.66

Bibliography

- Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. Tipografia italo-orientale. Grottaferrata, 1919.

- Barzilai, Salvatose. L'irredentismo: ecco il nemico! Editore Il Circolo Garibaldi, 1890. Harvard University, 2002

- Lovrovici, Giovanni Eleuterio. Zara dai bombardamenti all'esodo (1943–1947). Tipografia Santa Lucia - Marino. Roma, 1974.

- Monzali, Vitale. The Italians of Dalmatia: from Italian unification to World War I. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 2009. ISBN 0802096212

- Petacco, Arrigo. A tragedy revealed: the story of Italians from Istria, Dalmatia, Venezia Giulia (1943–1953). University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 1998

- Rodogno, Davide. Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Publisher Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 2006 ISBN 0521845157

- Tommaseo, Niccolo. La questione dalmatica riguardata ne'suoi nuovi aspetti: osservazioni. (Tipografia Fratelli Battara, 1861). Harvard University Press. Harvard, 2007

- Večerina, Duško. Talijanski Iredentizam. Zagreb, 2001. ISBN 953-98456-0-2

- Vignoli, Giulio. I territori italofoni non appartenenti alla Repubblica Italiana. Giuffrè Editoriale. Milano, 1995.

- Vivante, Angelo. Irredentismo adriatico. Venezia, 1984.