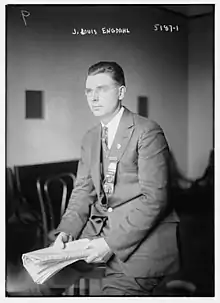

J. Louis Engdahl

John Louis Engdahl (November 11, 1884 – November 21, 1932) was an American socialist journalist and newspaper editor. One of the leading journalists of the Socialist Party of America, Engdahl joined the Communist movement in 1921 and continued to employ his talents in that organization as the first editor of The Daily Worker. Engdahl was also a key leader of the International Red Aid (MOPR) organization based in Moscow, where he died in 1932.

Biography

Early years

The son of Swedish Lutheran immigrants, J. Louis Engdahl (who went by his middle name, "Louis") was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on November 11, 1884. Engdahl was intelligent and well educated, he graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1907, having paid his way through school by working as a telegraph operator and as City Editor of the Minneapolis Daily News.

Political career

Engdahl was a member of the Socialist Party from 1908.[1] In 1909, he took a position as the Labor Editor of the Chicago Daily Socialist, assuming the mantle of Editor of that publication from 1910 until its termination in 1912.

Engdahl attended the Copenhagen Congress of the Socialist International in 1910 as a journalist on behalf of the Scandinavian Socialist Federation. He joined the Socialist Party of America in September 1912. Despite his traveling to Europe for the Scandinavian Federation, it does not seem that Engdahl ever directly participated in language federation politics in any way.[2]

Louis Engdahl was a Socialist candidate for US Congress from Illinois in 1916; for the Chicago City Council in 1917; again for Congress in the Illinois 7th C.D. in 1918. He also was on the Organizing Committee of the Communist Propaganda League of Chicago from its origin in 1918 until its demise in 1919.

In 1914, Engdahl assumed the position of Editor of The American Socialist, the Chicago-based official organ of the SPA. He continued to edit this newspaper each week until it was suppressed by postal authorities in 1917. Thereafter, he moved to the successor weekly publication, The Eye Opener, which he continued to edit until 1919.

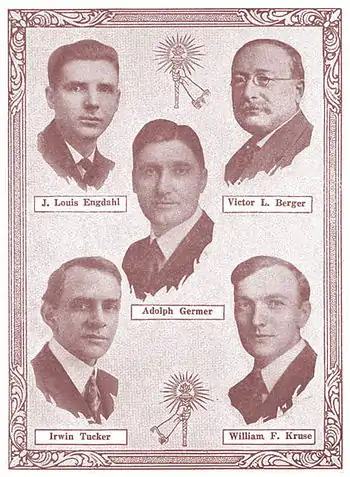

In February 1918, Engdahl's aggressive antimilitarism caused him to run afoul of the US Department of Justice, who targeted him as editor of the Socialist Party's weekly newspaper under the Espionage Act for undermining the American military conscription program. Along with his party comrades Adolph Germer, Victor L. Berger, Bill Kruse, and Irwin St. John Tucker, Engdahl was indicted by a grand jury. The quintet was brought to trial before the harsh Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis on December 6, 1918 (that is, after the war had ended), with the trial ending during the first week of January 1919. The jury found all five guilty as charged, and Judge Landis imposed a draconian sentence of 20 years in the Federal Penitentiary upon each. This sentence was later overturned on appeal for the reason of judicial bias.

Out pending appeal on $25,000 bond, Engdahl was a delegate from Illinois to the seminal 1919 Emergency National Convention of the Socialist Party, refusing to either support Adolph Germer, James Oneal, and the party regulars or to bolt the convention to join either of the fledgling Communist organizations — the Communist Labor Party of America or the Communist Party of America. Instead, Engdahl remained in the Socialist Party as a leader of the Left Wing faction, which congealed as the Committee for the Third International in 1920. Engdahl served as Secretary of this faction until it departed the party in the aftermath of the 1921 Convention.

From 1920 until July 1921, Engdahl served as editor of the Chicago Socialist, publication of Local Cook County of the SPA, until he was finally removed for political reasons. He was also the Secretary of Local Cook County SPA until his resignation on July 21, 1921.

After the disappointment of the 1921 Convention of the SPA, the Committee for the Third International left the party to mark the world with a short-lived existence as part of the Workers Council group — a small group of Communist adherents who sought to turn their backs on the sectarian infighting of the underground Communist parties. This pro-Comintern/anti-underground position proved to be timely, as in December 1921, at the Comintern's request, a "Legal Political Party" called the Workers Party of America (WPA) was established at a convention in New York. The Workers Council group was absorbed into the WPA at this time. He was elected to the 7 member "Administrative Council" of the WPA on Oct. 10, 1921. He stood as the WPA's candidate for Congress in the New York 12th C.D. in 1922. In January 1923 he was elected by the 2nd Convention of the WPA to the party's Central Executive Committee and sat on the inner circle of this group called the Executive Council.

Engdahl was employed as Managing Editor of the WPA's organ, The Worker, from 1922. When that paper moved to daily status in January 1924, Engdahl wore the hat of Editor of The Daily Worker, although as an adherent of the minority Pepper-Ruthenberg-Lovestone faction, he was saddled with a co-editor from the majority Foster-Cannon-Lore faction in February. He continued as an Editor at The Daily Worker until 1928.

In his 1952 memoir, Whittaker Chambers described him thus:

The paper's nominal editor was J. Louis Engdahl, a Communist in his late forties or fifties, who seldom paid any attention to what was going on, for, at the time, he was a prey to both political and emotional stresses of great intensity. He sat at the front of the office, at one of the two windows, usually staring fixedly out. At long intervals, he would beat out a page or two of copy, which was dull but at least intelligible. Engdahl himself was not. If you asked him a simple question, he would turn away and stare out the window. When you had about decided that he had forgotten you, he would turn around and fix you with his big round lenses that magnified his eyes to a slightly mad expression. Then he would grunt. Sometimes he mumbled a few words, scarcely audible . I do not remember hearing him utter five coherent sentences.

In his prime, he had been a Socialist in Wisconsin. He was now a follower of Jay Lovestone and had received the editorship of the Daily Worker as a prize in some factional deal. He felt that he was slipping. He also lived in terror of the telephone, for that seemed to be his wife's preferred way of reaching him, and he did not wish to be reached. When it rang, he would stare at it gloomily, then have someone else answer it. We always knew who was calling when we heard: "Comrade Engdahl is out of the office. No, I don't think he will be back."[3]

In February 1925, Engdahl was a candidate of the Workers (Communist) Party for Chicago City Alderman. He was the candidate of the W(C)P for Governor of Illinois in the fall of 1926.[4]

From May 1927 through February 1928, Engdahl was a member of the Presidium of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, representing the Workers (Communist) Party of America.[5] Engdahl remained in Moscow as the representative of the American Communist Party to ECCI until late in December 1928, when he was replaced by Bertram D. Wolfe.[6]

In July 1929, Engdahl was appointed by the CEC of the Communist Party as National Secretary of International Labor Defense (ILD), the party's legal aid arm.. He was named to the Polburo of the Communist Party in 1930 and was the party's delegate to the Comintern in Moscow in that same year. In 1930, he ran for Lieutenant Governor of New York with William Z. Foster on the Communist ticket. He was also a member and later Chairman of the CPUSA's Central Control Committee, as well as a member of the Presidium of International Red Aid (MOPR) — the international umbrella organization of the ILD.

Death and legacy

In Moscow on MOPR business, Engdahl died of pneumonia at the age of 48 on November 21, 1932. He was buried on November 23 following a service attended by many prominent communists including future East German president Wilhelm Pieck.[7]

Despite the fairly vast number of words he wrote throughout his career as a journalist, Louis Engdahl did not write any books and only a handful of pamphlets, including Debs and O'Hare in Prison (1919); The Tenth Year (1927); Gastonia: A Class Case and a Class Verdict (1929) and Sedition! (1930). He was also the subject of two pamphlets published by the Communist Party in 1932 and 1935, respectively.

Engdahl's papers are housed at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

See also

References

- G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) - VKP(b) i Komintern: 1919-1943 Dokumenty. Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2004; pg. 905.

- Henry Bengston, On the Left in America: Memoirs of the Scandinavian-American Labor Movement. [1955] Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999.

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 799 (total). LCCN 52005149.

- "Workers Party Enters Candidates in State Elections This Year," The Daily Worker, vol. 3, no. 211 (September 20, 1926), pg. 4.

- Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) - VKP(b) i Komintern: 1919-1943 Dokumenty, pg. 905.

- Theodore Draper, American Communism and Soviet Russia. New York: Viking Press, 1960; pg. 392.

- Buchwald, Nathaniel (24 November 1932). "Engdahl Funeral Held in Moscow". Daily Worker.

Works

Books and pamphlets

- Trade Unions and the Present Social Crisis. Chicago: National Office, Socialist Party, 1919.

- Debs and O'Hare in Prison. Chicago: Literature Dept., Socialist Party, 1919.

- 100 Years — For What? Being the Addresses of Victor L. Berger, Adolph Germer, J. Louis Engdahl, William F. Kruse and Irwin St. John Tucker to the Court that Sentenced Them to Serve 100 years in Prison. Chicago: National Office, Socialist Party, 1919.

- The Tenth Year: The Story of the Rise and Achievements of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics, November 7, 1917, to November 7, 1927. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1927.

- Gastonia: A Class Case and a Class Verdict. New York: International Labor Defense, 1929.

- International Labor Defense. New York: International Labor Defense, 1929.

- Sedition!: To Protest and Organize Against War, Hunger and Unemployment. New York: International Labor Defense, 1930.

Articles

- "The War Censor Arrives in America," The American Socialist, v. 2, no. 19, whole no. 159 (November 20, 1915), pg. 1.

- "Party Demands Capitalists Pay Expenses of Conflict," Milwaukee Leader, vol. 6, no. 109 (April 14, 1917), pp. 1, 12.

- "Rose Pastor Stokes Asks Privilege to Return to Socialist Party Ranks," The Eye Opener, v. 9, no. 26 (January 19, 1918), pg. 4.

- "Food Kaisers," Organizational Leaflet No. 15. Chicago: National Office of the Socialist Party of America, March 1918.

- "C.E. Ruthenberg Hurried from Canton Work House To Testify in Debs' Free Speech Trial," Milwaukee Leader, vol. 7, no. 235 (September 11, 1918), pp. 1–2.

- "Debs in Prison," in Debs and O’Hare in Prison. Chicago: National Office, Socialist Party, n.d. [1919]; pp. 11–23.

- "The Chicago Socialist Trial," in The American Labor Year Book, 1919-20. New York: Rand School of Social Science, 1919.

- "A Reply to Debs," The Worker, vol. 5, whole no. 237 (August 26, 1922), pg. 2.

- "Capitalism's Howling Jackals Are Heralds of the New Day," The Worker, vol. 6, whole no. 269 (April 7, 1923), pg. 3.

- "An Open Letter to David Karsner," The Worker, vol. 6, whole no. 271 (April 21, 1923), pg. 6.

- "Romance in Journalism: From The Chicago Daily Socialist to The Daily Worker, The Liberator, whole no. 66, October 1923, pp. 16–17.

Further reading

- Elizabeth Lawson, Scottsboro's Martyr: J. Louis Engdahl. New York: International Labor Defense, n.d. [1933].

- Harriet Silverman, J. Louis Engdahl: Revolutionary Working Class Leader New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

External links

- Finding Aid for the J. Louis Engdahl Papers, Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved February 25, 2010.