J. Searle Dawley

James Searle Dawley (October 4, 1877 – March 30, 1949) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, stage actor, and playwright. Between 1907 and the mid-1920s, while working for Edison, Rex Motion Picture Company, Famous Players, Fox, and other studios, he directed more than 300 short films and 56 features, which include many of the early releases of stars such as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Pearl White, Marguerite Clark, Harold Lloyd, and John Barrymore.[2][3] He also wrote scenarios for many of his productions, including one for his 1910 horror film Frankenstein, the earliest known screen adaptation of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel.[4] While film direction and screenwriting comprised the bulk of Dawley's career, he also had earlier working experience in theater, performing on stage for more than a decade and managing every aspect of stagecraft. Dawley wrote at least 18 plays as well for repertory companies and for several Broadway productions.[5]

J. Searle Dawley | |

|---|---|

Dawley, c. 1919 | |

| Born | James Searle Dawley October 4, 1877[1] Del Norte, Colorado, USA |

| Died | March 20, 1949 (aged 71) |

| Occupation | Film director, producer, screenwriter, stage actor, playwright |

| Years active | 1894–1938 |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Owen Givens (1918–1949; his death) |

| Children | None |

Early life and stage career

Born in Colorado in May 1877, Dawley was the youngest of three sons of Angela (née Searle) and James Andres Dawley. Young "Jay" obtained his elementary education in Denver, continued his public schooling there through the eighth grade, and later attended the Scott Saxton College of Oratory, also located in Denver.[6][lower-alpha 1] According to his physical description recorded on his 1918 military registration card, Dawley as a child permanently lost sight in his right eye, an impairment that no doubt posed additional challenges for him later as a stage performer and as a film director, especially in composing scenes on sets and on location.[1][lower-alpha 2]

On September 9, 1895, at the age of 17, Dawley performed professionally on stage for the first time at the Grand Opera House in New York City, cast as François in the Lewis Morrison Company's production of Richelieu.[7] It was at that time when Morrison, the head of the theatrical group, urged the young actor to stop using his nickname "Jay" Dawley as a performer and to choose a better, more distinguished credit for the company's cast listings. Dawley heeded the advice and began emphasizing and consistently using his middle name, which was his mother's maiden name, "Searle".[7] Three years later, now billed as J. Searle Dawley, he was serving as stage manager for Morrison while still performing in several of the company's most popular presentations such as Faust, Yorick's Love, Master of Ceremonies, and Frederick the Great.[8]

1899-1907

Dawley's stage career continued into the opening decade of the twentieth century. He left the Morrison Company after five years to perform on the vaudeville circuit between 1899 and 1902. He then returned to the "legitimate" theatre in New York, joining the Edna May Spooner Stock Company in Brooklyn. While working for Spooner, Dawley acted, managed the company's productions, and also demonstrated his considerable talents as a dramatist despite possessing only an eighth-grade formal education. He wrote and produced no less than 15 plays during his five years with that stock company. By 1907 he left Spooner to begin working in the rapidly expanding motion-picture industry. Despite his career move to film, he continued to write plays, including three Broadway productions, which were presented in 1907 and 1908: The Dancer and the King, The Girl and the Detective, and A Daughter of the People.[5]

Film career

On May 13, 1907, Dawley began his motion-picture career in New York City. Edwin Porter, the head of production for Edison Studios, hired him that day, agreeing to pay him $60 a week ($1,646 today) to serve as a director at the company's main film facilities, which were located in the Bronx at the corner of Decatur Avenue and Oliver Place.[9] Dawley's considerable stage experience proved to be very useful in managing his early screen productions. His first directorial project was the now-lost 14-minute comedy The Nine Lives of the Cat, a story about a family's troublesome pet cat that repeatedly returned home after different people attempted to abandon or kill it.[lower-alpha 3] Dawley's numerous frustrations working with that production's feline star and problems with the film's supporting actress prompted the director to remark later, "'I hardly thought I was going to like the motion picture business.'"[9]

After experiencing some initial frustrations in his new position at Edison, Dawley quickly established himself as a reliable and prolific director for the studio. He demonstrated an ability to administer efficiently a wide range of releases for the company, often completing two or more films in a single week. Ultimately, he would direct over 200 one-reelers for Edison.[10] A few of his more notable releases during the remainder of 1907 and through 1909 include Cupid's Pranks, Rescued from an Eagle's Nest, Comedy and Tragedy, The Boston Tea Party, Bluebeard, The Prince and the Pauper, Hansel and Gretel, an adaptation of Jules Verne's novel Michael Strogoff, as well as an adaptation of Johann von Goethe's early nineteenth-century play Faust, a story Dawley had already performed many times on stage as a member of the Lewis Morrison Company.[3][11] The 1908 action adventure Rescued from an Eagle's Nest is only a seven-minute film, but it is noteworthy for its special effects by Richard Murphy and for featuring an early screen performance by D. W. Griffith.[12][lower-alpha 4] In the short, the future legendary director portrays a woodsman who rescues his child after the infant is carried away by an eagle.

Frankenstein and other releases, 1910-1912

By 1910, Dawley was directing ever-more elaborate productions for Edison, although the company resisted and would continue to resist the growing trend in the film industry to create longer motion pictures in two- and three-reel formats. Among the numerous "one-reelers" he created at that time were an adaptation of Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol (1910) and presentations of two historic naval battles: The Stars and Stripes (1910), which depicted John Paul Jones' victory over HMS Serapis in 1779, and The Battle of Trafalgar (1911), a portrayal of British Admiral Lord Nelson's triumph in 1805 over a combined fleet of French and Spanish warships.[13][14] Both of those productions required Dawley to oversee the creation of large maritime sets inside Edison's Bronx studio, including the construction of upper and lower decks of sailing vessels, as well as fabricating simulated views of sea battles using small-scale models and silhouettes of warships.[15][lower-alpha 5]

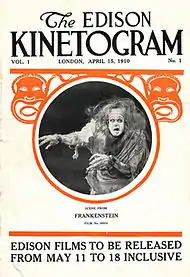

Among Dawley's most notable directorial works and screenplays in this period is his 14-minute 1910 horror "photoplay" Frankenstein, which is the earliest known screen adaptation of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel.[4] The production, loosely based on that "harrowing tale", was also staged and filmed in three days at Edison's Bronx facilities in mid-January 1910.[16][17] Copies of the film survive and showcase another special effect employed by Dawley in simulating on screen the creation of Frankenstein's monster. The burning of a papier-mâché human figure molded around a skeletal frame was filmed separately in reverse or "back-cranked" in the hand-driven camera, then that footage was spliced into the master negative for producing the final prints for release and distribution.[18][lower-alpha 6] The reversal of the action on the red-tinted footage produced a "creation" scene in which the monster, with its wired arms flailing, appears to form slowly and then rise from within "a cauldron of blazing chemicals". In a March 1910 issue of The Film Index, an advertisement for Dawley's film describes the effect as a "photographic marvel".[19][20]

By 1911, Dawley was one of four full-time directors under contract with Edison. The New York-based trade journal The Nickelodeon in its February 11 issue that year introduces the four men to its readers and highlights Dawley's speciality among his fellow directors:

The producers of the Edison Company, by which is meant the stage directors who superintend and are responsible for the action of the picture as well as the development of the plot used, are four in number—Messrs. J. Searle Dawley, Ashley Miller, C. Jay Williams and Oscar C. Apfel. A producer naturally, like any other man, develops a particular aptitude for some certain line of work. Mr. Dawley, for example, has put on some of the biggest and most sumptuous productions the Edison Company has ever produced. As specimens of his work may be mentioned "The Stars and Stripes," "Through the Clouds," "The Red Cross Seal", "Eldora, the Fruit Girl," "An Eventful Evening," "The Black Bordered Letter," "The Doctor" and "The Price of Victory."[21][lower-alpha 7]

Travels to California

In 1910 Dawley traveled to California to establish a presence for Edison Studios on the West Coast and to assess Edison's potential for expanding its operations there like other film companies. Dawley made arrangements to rent production space in Long Beach and develop plans for possible new facilities. His initial "film-plant" activities for Edison in that location should not be confused with a "huge" $10,000,000 project being built the same year in Long Beach by Edison Power Company. That company, like Edison Studios, was a subsidiary of Edison Manufacturing Company and in 1910 began construction on the largest electrical plant west of Chicago, one that would ultimately "generate 100,000 horse power" for customers in and around Long Beach.[22] Despite his travels back and forth to California for his own work there between 1910 and 1912, Dawley still staged and directed most of his remaining films for Edison at its Bronx studio in New York.

Dawley by 1912 increasingly spent more time writing screenplays and adapting scenarios for Edison, such as Mary Stuart, Partners for Life, and Charge of the Light Brigade.[3] For the latter film, which he did direct and complete in California, he incorporated scenic footage he took while passing through Cheyenne, Wyoming, when he and his company of players and crew traveled from New York to California, meandering their way across the country on an "extensive picture making tour".[23] It was at this time when Dawley tried to convince Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor and head of the entire Edison corporation, to allow him to create longer films, to expand beyond the company's production of only one-reel pictures, which generally had maximum running times of just 15 minutes.[24][lower-alpha 8] Edison, however, who apparently had little confidence in the attention span of moviegoers, brushed aside the experienced director's recommendation, and tersely replied, "'Dawley, the public won't sit through two reels.'"[25]

Famous Players Film Company and Dyreda

In 1913 Edwin Porter hired Dawley again, but this time to work with him for Adolph Zukor's recently established studio, Famous Players Film Company.[10] Dawley's departure from Edison was at least partially motivated by his desire to make longer, more complex motion pictures. Working out of that Famous Players' facilities on West 26th Street in New York, he directed the first 13 releases of the new company, with his debut project being Tess of the D’Urbervilles, which was released in September 1913.[26] There he worked with array of established and future stars. He directed John Barrymore in the celebrated stage actor's first feature film, the romantic comedy An American Citizen.[8] He also directed future megastars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford in some of their early screen appearances.[8][lower-alpha 9]

Dawley resigned from Famous Players on May 16, 1914.[27] Although he had been with that studio for only a year, the volume and quality of his work there established his reputation in the film industry as "the man who made Famous Players famous".[28] Dawley departed Famous Players to join Frank L. Dyer and J. Parker Read, Jr. in establishing the film company Dyreda, the name of which was formed by combining the first two letters in each man's surname. Their independent company in the fall of 1914 made arrangements with World Film Corporation to distribute Dyreda releases and later merged with Metro Pictures.[28]

Motion Picture Directors Association, 1915

In the years prior to World War I, as the motion picture industry in the United States continued to expand production and its influence on American culture, some media critics and sectors of the general public began increasingly to accuse the film industry of immoral, destructive behavior both on and off the screen. Dawley in 1915 became one of the 26 founding members of the Motion Picture Directors Association (MPDA), which was established in Los Angeles, California that year. Among the professional organization's expressed goals was "'to exert every influence to improve the moral, social and intellectual standing of all persons connected with the motion picture producing business.'"[29] The following year, on November 14, a New York chapter was created for directors on the East Coast, which for a few more years would remain the center of motion picture production until California attained that status. In addition to encouraging responsible professional and personal behavior in the film community, the MPDA also pledged in its founding principles to aid any of its "distressed members" as well as "their wives, widows and orphans."[29] Dawley served as the second president of the New York chapter and remained an active and influential member of the association as the chairman of its board of trustees.[8]

1916-1930s

Dawley returned to Famous Players (later Paramount Pictures) in 1916, and among many other projects, he directed Marguerite Clark in a series of pictures that brought her fame in the film world second only to Mary Pickford.[30] Dawley's films with Clark include Mice and Men (1916), Out of the Drifts (1916), Molly Make-Believe (1916), Silks and Satins (1916), Little Lady Eileen (1916), Miss George Washington (1916), Snow White (1916), The Valentine Girl (1917), Bab's Diary (1917), Bab's Burglar (1917), Bab's Matinee Idol (1917), The Seven Swans (1917), Rich Man, Poor Man (1918), and Uncle Tom's Cabin (1918).[31]

After two years with Famous Players, Dawley left the studio once again, a departure that coincided with his getting married in June 1918 and then taking several months off work for an extended honeymoon to Alaska and other locations.[32] Once he and new wife Grace returned home to New York, he began freelancing as a director for several years before joining Fox Films in 1921.[lower-alpha 10] The last feature film he directed was the drama Broadway Broke (1923), which was produced by Murray W. Garsson Productions and distributed by Lewis J. Selznick.[33] In its December 30, 1923 review of Broadway Broke, the trade paper The Film Daily judges Dawley's direction as being "particularly good", adding that he "certainly made fine use of [the] material and provided [A-1] entertainment".[33] Months later, Dawley made his final directorial works, two experimental sound shorts he did in collaboration with American inventor Lee de Forest: Abraham Lincoln (1924) and Love's Old Sweet Song (1924).

After his work ended as a director, Dawley tried "various businesses" during the late 1920s and 1930s that related to radio broadcasting, newspaper writing, and the development of sound-film technologies.[10] In a seemingly odd job for a highly accomplished film director, Dawley between late July and November 1930 wrote a syndicated human-interest and romance column for The Arizona Republican newspaper in Phoenix. Titled "Sweet Arts Of Sweethearts", Dawley's column entertained and instructed readers with stories and history lessons about courtship, betrothal, and wedding customs in different countries and religions around the world.[34] Some of the installments of his column addressed topics such as "The Love Shirt of Sweden", "The Three Ways of Love", "Love Superstitions of Germany", and "Rough Love in Savageland".[34]

Retirement

The given year when Dawley finally retired from working varies in obituaries and in other news items about his career. Federal census records document that Dawley and his wife Grace were living in New York City in a rented home in Manhattan in 1930 and then in a different rented property in Queens in 1940. At both locations, perhaps indicative of the couple's need for additional income, the Dawleys sublet rooms in their residence to as many as five "lodgers".[35][36] Nevertheless, in the 1930 census Dawley still identified himself professionally as "Director/Motion Pictures".[35]

In its 1949 obituary for Dawley, The Boston Globe states that the former director retired in 1938, although notices of his death in other newspapers at the time, including The New York Times and Los Angeles Times, report that he retired in 1944.[37] Data in the federal census of 1940 also indicates that Dawley was not yet fully retired by then, that he remained actively working, at least as a writer. In that census he identifies himself as a self-employed "Author/Private".[36]

Personal life and death

On June 14, 1918 in Denver, Colorado, Dawley married Grace Owens Givens, a native of Illinois.[38] The couple remained together over 30 years, until Dawley's death in 1949. On March 29 that year, at age 71, Dawley died of undisclosed causes at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in Los Angeles, California.[39] A memorial service was held for him three days later in Los Angeles, followed by the "inurnment" of his ashes in the columbarium at the Chapel of the Pines Crematory. Silent film star and producer Mary Pickford and director Walter Lang, who early in his career was an assistant to Dawley, were among those who spoke at the service.[40] Dawley was survived by his wife Grace and his brother Hubert "Bert" Dawley. Later in 1949, Grace Dawley donated a selection of her husband's personal papers, scrapbooks, and several of his Edison production scripts to the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, California.[10]

Partial filmography

- The Nine Lives of a Cat (1907)

- The Trainer's Daughter; or, A Race for Love (1907)

- A Little Girl Who Did Not Believe in Santa Claus (1907)

- Cupid's Pranks (1908)

- Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (1908)

- The Boston Tea Party (1908)

- Comedy and Tragedy (1909)

- Faust (1909)

- Hansel and Gretel (1909)

- Frankenstein (1910)

- A Christmas Carol (1910)

- The Stars and Stripes (1910)

- Through the Clouds (1910)

- The Red Cross Seal (1910)

- An Unselfish Love (1910)

- A Central American Romance (1910)

- The Cowpuncher's Glove (1910)

- A Daughter of the Mines (1910)

- Eldora, the Fruit Girl (1910)

- The Princess and the Peasant (1910)

- Riders of the Plains (1910)

- The Ship's Husband (1910)

- The Song That Reached His Heart (1910)

- The Stolen Claim (1910)

- An Eventful Evening (1911)

- The Black Bordered Letter (1911)

- Between Two Fires (1911)

- The Doctor (1911)

- The Price of Victory (1911)

- The Battle of Trafalgar (1911)

- Charge of the Light Brigade (1912)

- Lord and the Peasant (1912)

- The Diamond Crown (1913)

- The Old Monk's Tale (1913)

- The Daughter of the Hills (1913)

- On The Broad Stairway (1913)

- Hulda of Holland (1913)

- Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1913)

- In the Bishop's Carriage (1913)

- Chelsea 7750 (1913)

- The Daughter of the Hills (1913)

- An Hour Before Dawn (1913)

- Caprice (1913)

- The Port of Doom (1913)

- Leah Kleschna (1913)

- A Lady of Quality (1913)

- An American Citizen (1914)

- The Pride of Jennico (1914)

- Four Feathers (1915)

- Susie Snowflake (1916)

- The Rainbow Princess (1916)

- Snow White (1916)

- The Valentine Girl (1917)

- Bab's Diary (1917)

- Bab's Burglar (1917)

- Bab's Matinee Idol (1917)

- The Seven Swans (1917)

- Rich Man, Poor Man (1918)

- Uncle Tom's Cabin (1918)

- The Death Dance (1918)

- When Men Desire (1919)

- Married in Haste (1919)

- The Phantom Honeymoon (1919)[41]

- The Harvest Moon (1920)

- A Virgin Paradise (1921)

- Who Are My Parents? (1922)

- Broadway Broke (1923)

- Love's Old Sweet Song (1923) short film made in Phonofilm

- Abraham Lincoln (1924) short film made in Phonofilm

Notes

- In both the United States Census of 1930 and 1940, which are referenced in this article, Dawley stated that the highest level of education he attained was the eighth grade.

- The cause of Dawley's blindness in his right eye is not specified in available records. A closer inspection of Dawley's portrait (c. 1919) featured on this page shows that his eyes are noticeably set in different positions.

- The lost comedy The Nine Lives of the Cat is advertised in 1907 trade publications as being 955 feet in length, a near-maximum capacity of a standard silent-film reel, equivalent to a running time of 14.5 minutes.

- D. W. Griffith's casting in Rescued from an Eagle's Nest was actually his third appearance on screen, although his previous film work was as an extra.

- In the article in January 11, 1911 issue of The Nickelodeon, there is a reference to the construction of the ship's deck at Edison's Bronx studio for the battle film Stars and Stripes (1910). Quarterdeck and lower deck sets, including cannon, rigging, and other ship's furnishings were modified and recycled for the production of The Battle of Trafalgar, which was produced at the same site later in the year.

- Papier-mâché was an inexpensive, popular medium used at Edison and at other studios for fabricating all types of large and small props for film sets. Refer to Wikipedia's page about Edison's 1911 production The Battle of Trafalgar for references to the use of papier-mâché on set.

- In the early silent era in the United States, the terms "producer" and "director" were not positions that were as clearly defined from one another as in subsequent decades. Often the terms were used synonymously and applied interchangeably in film reviews and news items about motion-picture productions. In the quoted extract from the 1911 Nickelodeon article, the writer even attempts to clarify the responsibilities of a director.

- According to the cited source by Karin, a full 1000-foot reel of film in the silent era had a maximum running time of 15 minutes. Silent films were usually projected at a "standard" speed of 16 frames per second, much slower than the 24 frames of later sound films.

- One of the films in which Dawley directed Mary Pickford is Caprice (1913).

- Dawley's 1918 military registration card documents that at that time he and his wife Grace were residing at 215 51st Street in Manhattan.

References

- "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918", New York City, Local Board for Division 158; digital copy of original card with entries, including Dawley's birthdate, personally handwritten and autographed by him, September 12, 1918; subscribed archival database, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (TCJCLDS), Salt Lake City, Utah.

- "J. Searle Dawley", career profile, The Film Daily (New York, N.Y.), June 7, 1925, p. 71. Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Katz, Ephraim; revised edition by Fred Klein and Ronald Dean Nolan. "Dawley, J. Searle." The Film Encyclopedia. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 340. ISBN 0-06-273755-4.

- Picart, Caroline Joan; Smoot, Frank; Blodgett, Jayne (2001). The Frankenstein Film Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-313-31350-9.

- "J. Searle Dawley", Internet Broadway Database (IBDB), The Broadway League, Manhattan, New York. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Motion Picture Studio Directory", "DAWLEY, J. Searle", Motion Picture News (New York, N.Y.), October 21, 1916, pp. 108. Internet Archive. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Slide, Anthony. "Forgotten Early Directors", Aspects of American Film History Prior to 1920. Metuchen, New Jersey and London: 1978, p. 40. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Lowery, Carolyn. "J. Searle Dawley", The First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen. New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1920, p. 40. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Slide, "Forgotten Early Directors", p. 41.

- "James Searle Dawley Papers", Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, California. Online Archive of California (OAC). Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "J. Searle Dawley", American Film Institute (AFI), Los Angeles, California. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Rescued from an Eagle's Nest" (1907)", Progressive Silent Film List, Silent Era Company, Washington State. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Fourth of July Pictures", The Film Index (New York, N.Y.), July 18, 1910, p. 3. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR (Edison)", The Moving Picture World, September 9, 1911, p. 695. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Edison Photoplays and Player", The Nickelodeon, January 7, 1911, p. 14. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Frankenstein", Film, Video Collection, Library of Congress (LOC), Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "Frankenstein (1910)". AFI. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Obrapta, Clement Tyler. "Inside Thomas Edison’s FRANKENSTEIN Adaptation", November 20, 2019, Film Inquiry. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "EDISON FILMS/. Frankenstein", The Film Index, March 12, 1910, p. 10. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Marrero, Robert. Vintage Monster Movies. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975, pp. 4, 8-11, 30.

- "Producers of Edison Photoplays", The Nickelodeon, February 11, 1911, p. 157. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Edison Company to Erect Huge Plant at Long Beach", Los Angeles Times, January 4, 1910, section III, p. 1. ProQuest.

- "Edison Players Go West", The Moving Picture World (New York, N.Y.), July 27, 1912 p. 342. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- Karin, Bruce F. How Movies Work. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1987, pp. 46-47.

- "Movies Were Better Than Ever to Film Pioneer's Wife: GRACE DAWLEY", Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1966, p. C1. ProQuest.

- "J. Searle Dawley, Movie Pioneer, 71", The New York Times, March 30, 1949, p. 25. ProQuest Historical Newspapers; subscription access through The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

- "J. Searle Dawley", The Motion Picture News (New York, N.Y.), June 13, 1914, p. 73. Internet Archive. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "The World Film Corporation", advertisement, Variety (New York, N.Y.), October 24, 1914, p. 27. Internet Archive. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Slide, Anthony. The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. London and New York: Routledge, 2013. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-1135925543. Retrieved March 12, 2019 – via GoogleBooks.

- "Foreign news: 'Tough for Has'-beens'." Variety (London edition), June 8, 1927, p. 2. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "Marguerite Clark", catalog, American Film Institute (AFI), Los Angeles, California. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "Back from Alaska", Wid's Daily (New York, N.Y.), August 14, 1918, p. 1. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Broadway Broke", The Film Daily, December 30, 1923, p. 9. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Dawley, J. Searle. "Sweet Arts Of Sweethearts". The Arizona Republican (Phoenix), all 1930 issues: July 20, p. 35; August 3, p. 38; August 17, p. 36; September 21, p. 40; October 19, p. 44; and October 26, p. 45. ProQuest.

- "Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930", residence of "Dawley, J. Searle", Borough of Manhattan, New York City, April 5, 1930; digital image of original handwritten census page, archives of TCJCLDS.

- "Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940", residence of "Dawley, James S.", Borough of Queens, New York City, April 7, 1940; digital image of original handwritten census page, archives of TCJCLDS.

- "J. Searle Dawley", The Boston Globe, obituary, March 30, 1949, p. 22; “J. Searle Dawley, Movie Pioneer, 71", The New York Times, March 30, 1949, p. 25; "J. Searle Dawley" (obituary stating Dawley retired "five years ago"), Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1949, p. 27. ProQuest.

- "Colorado Statewide Marriage Index, 1853-2006", digital image of original typewritten card, "Marriage Record Report", Dawley to Givens, no. 69575, June 14, 1918, Division of Vital Statistics, State of Colorado; archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. FamilySearch.

- "J. Searle Dawley", obituary, Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1949, p. 27. ProQuest.

- Slide, p. 50.

- Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era. Midnight Marquee Press. p. 209.ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. Searle Dawley. |